Incorporating Shock Events into Aviation Demand Forecasting and Airport Planning (2024)

Chapter: 17 San Francisco International Airport

CHAPTER 17

San Francisco International Airport

Introduction

San Francisco International Airport (SFO) is classified as a large hub, commercial service airport under the NPIAS and is owned and operated by the City and County of San Francisco.

SFO is the second busiest airport in California (after LAX) and the primary international gateway airport for the San Francisco Bay Area. In 2019, the airport served 27.9 million enplaning passengers, of which 7.5 million (27%) were international enplanements. The airport is a hub for United Airlines for both domestic and international flights and functions as that carrier’s primary transpacific gateway airport. SFO is also a hub for Alaska Airlines. SFO is located on the shores of the San Francisco Bay with all four of its runways extending into the bay on artificial land built up from the foreshore.

The methodology is based on the analysis of SFO’s Draft Final Airport Development Plan (ADP), effectively its airport master plan. The current ADP was developed between late 2014 and early 2016 and sets out a comprehensive outlook for airport development to accommodate a long-term demand of approximately 35.5 million enplaning passengers.

The aviation activity forecasts were developed during the ADP’s production process and were accepted by the FAA in 2014 based on a 2013 baseline. Unlike traditional master plan forecasts that forecast every year or produce outputs at 5-year intervals over a 20-year timeframe, the ADP’s forecasts were developed for four timeframes: 2018, 2023, base-constrained, and high-constrained (SFO 2016, 2-1). The approach to developing the 2018 and 2023 timeframe forecasts followed a fairly standard process, incorporating regression analysis of historical determinants of air travel demand to project future O/D passenger demand and combined with projections of connecting passenger activity along with market intelligence on airline network development and fleet mixes to arrive at the passenger and aircraft movements forecasts for those two timeframes.

Unlike a traditional master plan with a central or base-case scenario with “high” and “low” alternative scenarios, the ADP has taken a different approach to its long-term demand forecast. The ADP provides a medium-term forecast for the years 2018 and 2023 and a pair of long-term constrained forecasts for design and planning purposes. Both long-term demand levels are constrained scenarios that are founded on the assumption of the maximum number of annual operations given a fixed airfield capacity and layout, with passenger levels being forecast from assumptions regarding fleet mix, gauge of aircraft, and load factors. As expanding the number of runways or taxiways is not part of the ADP’s plans, the long-term traffic scenarios take a constrained approach based on airfield design and estimated operations and passenger traffic from that constraint. The base-constrained and high-constrained demand levels were designed to simulate the years 2028 and 2033, respectively.

This approach unties future forecast activity levels from specific timelines and instead links the forecast to “the maximum practical capacity of SFO’s airfield.” Given the approach to developing the forecasts is based on projected airside capacity, it is implicit that the designs should reflect that level of activity whenever it may happen as opposed to a more traditional forecasting/planning approach, which generally provides a timeline for the activity level. The ultimate high-constrained level of 35.5 million enplaned passengers per year could occur in 10, 20, or 50 years from the ADP’s publishing, but the level of development to serve that implied level of traffic would be suitable, nonetheless. However, for planning, the base-constrained and high-constrained demand levels were simulated as approximate 2028 and 2033 time periods.

It should be noted that in the language of the ADP, the forecast projection points—2018, 2023, base-constrained (2028), and high-constrained (2033)—are denoted as demand levels. The base-constrained and high-constrained demand levels are not alternative scenarios but forecasts of constrained demand given assumptions at two future time points, simulated as approximately 2028 and 2033 respectively, in what is effectively a single continuous scenario. For this case study, we retain the ADP’s usage of the term “demand level” when referring to the base-constrained and high-constrained forecast traffic levels.

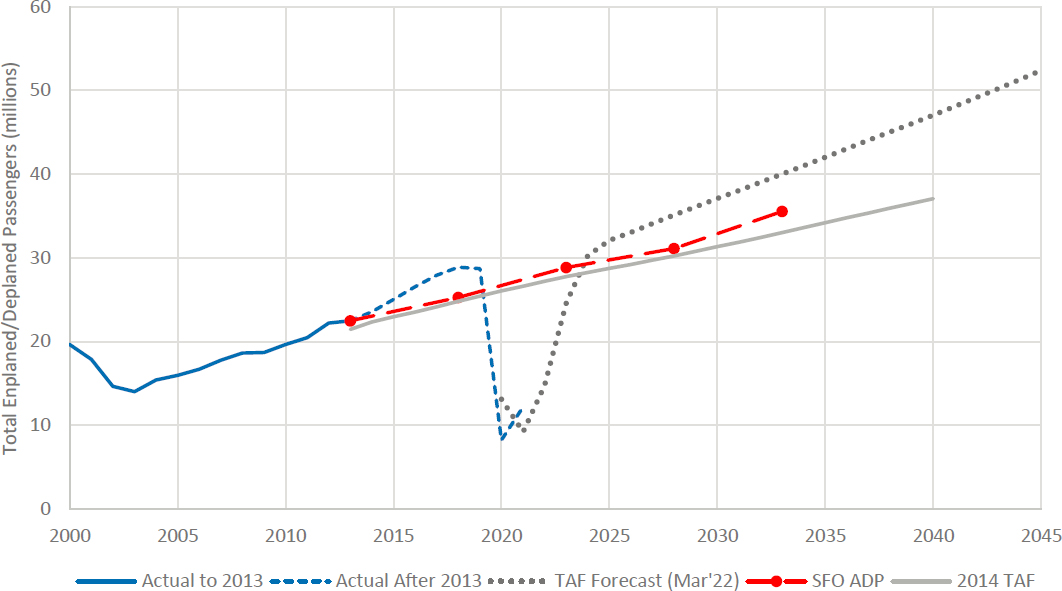

The forecasts of passenger enplanements from the SFO ADP are depicted in Figure 41. Historical enplanement data, up to 2021 is from SFO with the ADP forecast and the FAA TAF for SFO from March 2022. As the ADP’s forecast only provides data for specific years in 2018 and 2023, the base-constrained and high-constrained are plotted as traffic levels for 2028 and 2033, respectively, by design.

The forecast report considered a number of risks, described as “impact factors,” which could affect activity levels at the airport over the planning horizon. These impact factors cover a number of airline and market share developments (e.g., change in the market share of LCCs), economic growth variation, and facility constraints. While it is not stated explicitly, it can be inferred that

Figure 41. Forecast passenger traffic and demand levels at SFO (SFO 2016; FAA TAF).

these impact factors could lead to the airport having traffic levels above or below the demand levels projected in the forecast.

Application of the Methodology

The shock events examined in the case studies are for illustrative purposes only and are wholly the work of the research team. SFO reviewed these potential shocks and provided feedback to the research team. The information presented here remains wholly the work of the research team and does not represent the opinions of airport management or staff.

For the case study and this guide’s shock events methodology in general, it is important to keep in mind that the objective is not to devise new planning forecasts through the methodology. Instead, the objective is to examine potential shocks, unlikely as they may be, to explore how an airport’s business, operations, and community may be impacted by an unprecedented turn of events. They may be worst-case or best-case alternative scenarios that should be evaluated and may not necessarily result in airport traffic, planning, or finances returning to preshock trends.

In the specific case of SFO, its ADP develops a planning forecast based on the concept of demand levels for long-term planning. This concept develops future levels of constrained traffic in the long-term (i.e., 10 to 20 years from forecast development) that could be served based on airport constraints and future demand projections.

For this case study, we examine the effects of potential shocks on airport traffic levels specifically over the medium-term. Due to the approach of the ADP’s long-term traffic forecast of demand levels rather than a traditional unconstrained forecast of X traffic in Y future year, the methodology looks at what potential long-term (years 10+) impacts may be without developing specific quantified traffic levels.

Step A: Identify Shock Events of Interest

The ACRP research team developed a set of potential shock events based on their research of past shock events and information on forecast assumptions and risks (impact factors) described in SFO’s ADP. The list of identified shock events is shown in Table 10 and is based on an outlook taking place in 2016 at the time of the ADP’s completion.

Step B: Develop Scenario Forecasts That Incorporate Shock Events

From the shock events described in Step A, three were selected to be further analyzed through scenario forecasts. These events are projected to occur in 2014, 1 year after the last historical year of the ADP’s forecast period.

-

Scenario Forecast 1: Loss of a significant carrier

- One of SFO’s major carriers with both O/D and connecting operations at the airport is assumed to leave SFO. The carrier accounts for 8% of the airport’s total capacity across a mix of both domestic and international services (but is primarily domestic). The loss of the carrier also impacts passenger traffic on connecting services by the carrier’s alliance partner, particularly alliance partners on services to Asia and the Pacific.

- The event is assumed to occur at the beginning of the second quarter (i.e., start of the Northern Summer scheduling season) resulting in a 6.5% loss in capacity in the first year and a 1.5% loss in the following year. These losses translate into a 5.5% and 4.8% reduction in traffic versus the ADP forecast for 2014 and 2015, respectively.

Table 10. Identified shock events based on 2016 outlook for SFO.

| Event | Description of Impact | Timeline and Aftermath |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of significant carrier | Aside from United Airlines, SFO had six carriers with significant operations with activity levels ranging from 3% to 9% of total annual airport capacity. The exit of one of these major carriers would have a substantial impact on available capacity, though it could be expected that some of that capacity would be backfilled by the remaining carriers. A secondary factor where an existing carrier leaves SFO, and instead bases at another airport in the Bay Area (e.g., OAK or San Jose Mineta International Airport), would likely have an additional negative impact as it would represent a shift in the market demand with less ability for existing carrier(s) to recapture demand and capacity. |

Starting in the second quarter, one of the airport’s major carriers accounting for 8% of total airport capacity, eliminates its capacity from the airport. The result is a loss of 6% in capacity in the first year, with a loss of 2% in capacity in the following year. It is assumed that this carrier operates both domestic and international services and impacts originating and connecting traffic, though the rate of connecting traffic is less than the overall average for the airport. The impact on passenger traffic is not likely to be 1-to-1, with existing carriers absorbing some of the lost capacity in the immediate time period. Over the medium-term (1–4 years) some portion of the exiting carrier’s capacity is recovered. Over the long-term (5+ years) other carriers will likely backfill lost capacity, and fundamental demand would not likely be impacted versus the ADP’s long-term demand level forecasts. |

| Downsizing of United hub | Specific to the operations of United Airlines, it is possible that the carrier could downsize its hub operations at SFO. In 2013, United accounted for more than 45% of total capacity at SFO and was one of the primary drivers of connecting traffic at the airport. A reduction in capacity would have an impact on both originating and connecting traffic, and a downsizing of the hub would likely be realized by reducing connecting activity at SFO. | In 2013, the last historical year for this analysis, United accounted for 45% of SFO’s total scheduled capacity and an estimated 77% of connecting passengers. The most significant change in network structure is the major reduction in United’s international network at SFO. Transpacific and transatlantic services are primarily impacted, but Canada and Mexico are less impacted. The airline’s domestic network is also substantially reduced, with frequencies and destinations cut back and a resulting network focusing primarily on O/D markets rather than acting as a connecting hub. The immediate impacts are assumed to be as follows: The carrier’s connecting activity is reduced by 60%, approximately a 45% loss in total connecting traffic at the airport. United’s international capacity is reduced by 40% for an estimated loss of 15% in international passengers. United’s domestic capacity is down by 50%, resulting in a 30% loss of domestic passengers. However, as the fundamental demand economics of the market are assumed to be unaffected, passenger traffic is likely to recover over the coming years as other carriers backfill the market both to meet O/D demand as well as utilize SFO for further connecting activities. Over the long run, it may result in constrained demand levels being reached later than in the baseline ADP assumptions, depending on the pace of capacity recovery. |

| Earthquake | The San Francisco Bay Area is an active seismic zone where resilience to earthquakes is a design and planning requirement. SFO is built primarily upon artificial landfill over an estuarine mudflat. Because of that underlying geology, the airport lands are at high risk for soil liquefaction and thus damage to built structures in the event of an earthquake. (U.S. Geological Survey and the California Geological Survey 2006) While the | A major earthquake hits the San Francisco Bay Area causing widespread damage. Traffic at the airport is halted for a short period (less than 1 week) while surrounding infrastructure, such as highways and public transit, is similarly negatively impacted, reducing access to the airport. A major earthquake would also have negative impacts on the local economy with disruption of business activities and impacts on households through damage or loss of life. |

| facilities at the airport have been designed for seismic resistance, there is a risk that a severe earthquake could lead to substantial damage of airport facilities such as terminal buildings, access roads, airside infrastructure, or utilities—any of which could impair normal operation of the airport for potentially weeks or months. | In a worst-case scenario, airport infrastructure such as terminal buildings or runways/taxiways are damaged and require repair to return them to operational status. Return to full operations in terms of capacity may take from weeks to even months, but the effects are likely to be transitory. The oldest terminal structures are most susceptible to earthquake damage as newer buildings (e.g., the International Terminal Building) are built to high seismic standards and designed to remain functional even in the event of an earthquake. |

|

| Climate change shocks | An extreme weather event, coupled with rising sea levels, leads to serious structural damage to the airfield through water overtopping and breaching the seawalls or inundation of the airside. | An extreme storm leads to a complete closure of all airport operations for a relatively short duration—a week, for example. However, the shock damage to the airside renders the portions of Runways 11/28 (both L and R) east of the interception with Runways 01/19 unusable. Taxiway L is also impacted and unsuitable for use. It is assumed that it will take 3 months for the airside infrastructure to be repaired to a mostly operational, but full return of the airside does not occur until the next year. The loss of operations of SFO’s two longest runways and a major taxiway has an immediate impact on the operational capacity of the airport. The most significant impact is the inability to operate a number of long-haul flights due to the longest remaining operational runway being less than 9,000 ft. As a result, many long-haul operations are suspended with demand flowing over to other gateway airports in the United States. The impact on passenger traffic is assumed to be resolved within 1 year, though there is the possibility that some airlines may choose to move operations to another airport. The financial cost of the shock event is high. |

| Significant growth in Asia and Latin American markets | Economies, and thus passenger demand from Asian and Latin American markets, grow faster than expected, leading to a long-term increase in growth of O/D and connecting traffic at SFO. | Growth in the economies of Asian and Latin American markets is listed as one of the key impact factors in the ADP’s forecast. Faster than expected growth in these regional economies would result in higher growth of international traffic—both O/D and connecting—at the airport. Faster growth would lead to traffic levels above the medium-term forecast and reach constrained forecast traffic levels sooner than otherwise anticipated. Such growth also carries a risk that this demand could slow or collapse in the future if a shock increase in economic growth is accompanied by a particularly harsh recession. This shock to demand would be experienced over a long period, but over the long run would result in higher traffic levels in a traditional, unconstrained demand forecast. Due to the constrained nature of the ADP’s demand level projections, it would likely manifest as a reallocation of traffic toward these markets. Facility investments specific to international traffic may need to be accelerated. Additionally, services specifically targeting the demands and needs of travelers to and from these regions may need to be implemented as the demand profile of the airport’s traffic shifts due to this shock. |

| Event | Description of Impact | Timeline and Aftermath |

|---|---|---|

| Dot-com bubble burst, Version 2 | A major collapse in the Bay Area’s tech economy results in reduction in employment and general economic activity in the airport’s catchment area. Given the size of the tech economy and its importance to the overall economy of the San Francisco Bay Area, a shock to this industry would simulate a localized recession or downturn with potentially wide-ranging effects. | The San Francisco Bay Area and SFO’s primary catchment area has the highest concentration of tech and IT companies in the United States. A major downturn in this industry would have outsized effects on the local economy and SFO’s traffic. The 2000 dot-com bubble bursting was associated with a slowing of growth and then negative growth seen in the second half of 2000 and into 2001 (prior to the impacts of the 9/11 terrorist attack). For the first 8 months of 2001 (pre-9/11) monthly traffic at SFO was down an average of 8% versus the previous year. While the bubble bursting also coincided with the early 2000s recession in the United States (March through November 2001), SFO likely suffered reductions in travel demand as the tech industry shrunk with carry-over impacts to other sectors of the economy all impacting travel demand. A shock collapse or decline in the local tech industry would likely be realized not as an immediate drop in traffic but as a slower decline or reduction in growth that could last for many years or even be permanent. |

| Terrorist attack | A terrorist attack occurs in the United States leading to a temporary closure of national airspace and a reduction in travel demand following the attack. | Following the 9/11 terrorist attack in 2001, SFO saw annual traffic decline by 9% in 2002 along with a 30% decline in traffic in the last 4 months of 2001. The terrorism event had a significant impact at SFO and around the United States, but the impacts were also conflated with the lingering impacts of the dot-com crash on the local economy and fundamental underlying demand. A terrorist event that targets the U.S. aviation system would likely see similar—but less negative—effects on traffic at SFO, including a short, sharp downturn in traffic during the month following the event, along with a lagging short-term recovery in demand as travelers choose not to travel. Future terrorist attacks may also result in new security measures at airports or by airlines, which may also reduce demand in the short term (typically through substitution to other modes) but are not likely to see the same type of transformative impacts that post-9/11 security changes had on airport planning. |

| Pandemic | The airport is affected by a regional, national, or global pandemic, negatively impacting passenger demand and operational capacity. | In 2003, SFO suffered a downturn in traffic between February and July due to the SARS pandemic. The SARS outbreak primarily affected travel to and from Asia as the pandemic did not cause significant disruptions within the United States. Over the 7 months of the pandemic (February through July), international enplanements at SFO were down 16% versus 2002 and down 25% compared to 2000 levels (prerecession and 9/11), though traffic downturn drivers at SFO were conflated with the localized economic slowdown caused by the post-dot-com crash era. Domestic enplanements did see some declines but only at a fraction of the impact on international traffic. A similar SARS-type pandemic would be expected to see a decline in international traffic for a period of 3 to 9 months if the pandemic was foreign-based. As a major transpacific gateway airport for the United States, SFO is particularly exposed to pandemics or disruptions in Asia. A pandemic regionally or nationally within the United States, even of a SARS-type, would likely have a much more significant impact on traffic at SFO as it would negatively impact domestic demand (which has historically accounted for approximately 75% of SFO’s passengers). |

-

- By the second year, traffic levels have recovered to preshock levels through both organic growth of the market and through other carriers partially backfilling lost capacity and/or expanding into markets now left underserved or unserved.

- Over the medium-term, it is projected that total passenger traffic would likely reconverge to preshock forecast levels as other carriers are able to backfill lost capacity. As underlying demand in the market was not impacted (e.g., through an economic shock) sufficient demand would remain in the market to incentivize other carriers to deploy capacity and fleet assets over time to meet demands.

-

Scenario Forecast 2: Downsizing of United hub

- United Airlines, SFO’s largest carrier, engages in a strategy of downsizing its operations at SFO. The carrier made up 45% of the airport’s total scheduled capacity in 2013 and approximately 78% of the airport’s connecting traffic.

- In the downsizing action, the carrier reduces its connecting activity at the airport by an assumed 60%. This results in an estimated 50% reduction in domestic connecting passengers and a 41% decrease in international connections. O/D passengers are projected to decline by a smaller amount (−24% for domestic and −8% for international, the latter having higher local O/D demand and therefore less exposed to shocks to connecting networks) as the shock forecast posits that the impact is based on reducing the hubbing activity with O/D less affected. However, domestic O/D is projected to be more negatively impacted as the airline is estimated to retain more of its international network for specific O/D demand, while the reduction in domestic capacity will negatively impact domestic O/D demand (which will likely spill to other domestic carriers).

- The total impact in 2014 is a 25% reduction in total passenger traffic versus the ADP forecast. An additional year of declining traffic is assumed as connecting passenger volumes decline further, and other carriers do not have sufficient fleet resources in such a short timeframe to significantly backfill capacity.

- By 2016, traffic growth is assumed to resume again both as a result of organic growth in the market (as forecast based on underlying economic demand) and as other carriers build up capacity to recover lost market share. However, in the short term, the airport will likely have a relatively lower share of connecting traffic than projected in the ADP forecast as carriers with backfilling capacity build expanded O/D and connecting networks.

- Over the medium-term (i.e., years 4 to 10) passenger traffic is expected to see an accelerated recovery process as other carriers backfill demand through fleet acquisitions and network shifts to meet underlying demand to and from the Bay Area. It is possible that many network carriers may build up strengthened hub operations at SFO to take advantage of the airport’s strategic location on the U.S. West Coast and for transpacific routes—potentially similar to LAX as an airport of many hubs. However, as fleet acquisitions and airline networks cannot instantly shift and based on the experiences seen at other airports that have seen major shocks to the hub activities of the largest carrier, it is projected that over this medium-term period, traffic would remain below ADP forecast levels as it recovers and rebuilds.

- The base-constrained and high-constrained demand levels would likely be unchanged due to this shock as long-run constrained estimates of traffic potential at the airport. Reevaluation of these demand levels may be necessary to determine how, with a wider mix of airlines providing hub networks at SFO, fleet mix, and aircraft types may change the projections for passenger and aircraft traffic at these future demand levels.

-

Scenario Forecast 3: Climate Change Shocks—Ocean Inundation

- Scenario forecast 3 examines the risk of major flooding and structural damage to the airport’s airside system in a major shock event due to sea level rise and increasing extreme weather activity arising from climate change. The specific damages are simulated as the closure of the

-

- eastern ends of Runways 10/33 (both runways) beyond the intersection of Runways 01/19. The event is assumed to happen at the beginning of August 2014.

- The entire airport is assumed to be closed for 1 week due to the damage. More extensive damage from inundation of the San Francisco Bay leads to severe structural damage to the Runways 10/33 infrastructure. A single runway is made available for use within 6 months, but full repair and return to normal operations do not occur until the following year.

- As a result of the damages, SFO is without its two longest runways, which impacts the ability of airlines to operate long-haul flights. Repair works limit the operational weight of aircraft taking off and landing such that a full return to preshock operations cannot occur until the following year. The longest operational runway at the airport during the shock is less than 9,000 ft, which limits airline operations of long-haul flights. Not until the airside repairs are fully complete will the restrictions on stage length be lifted.

- The effect on passenger volumes is assumed to be transitory and to be recovered within 2 years. While there will likely be an impact on airport finances, the airport’s Lease and Use Agreement and residual rate-setting method are anticipated to reduce the financial risk to the airport itself by spreading risk to its airline users.

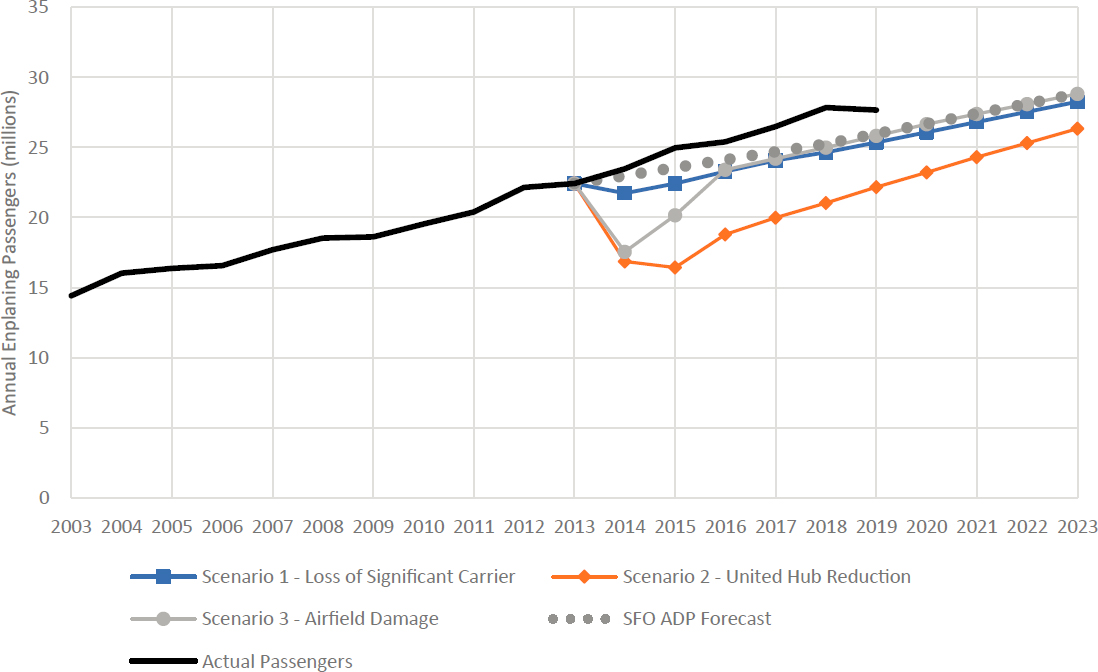

The scenario forecasts are depicted in Figure 42. Actual passenger traffic from 2003 to 2019 (excluding the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic) is included as well as SFO’s ADP forecast from 2013 to 2023. The scenario forecasts are all relative to the ADP’s forecast, rather than actual passenger growth, which was above forecast levels. While SFO-3, showing the potential impact of major damage to the airside infrastructure, is projected to have only a relatively modest impact on traffic—compared to the other two scenario forecasts—it is possible that this scenario could bear a heavy financial burden to finance repair costs.

Step C: Scenario Implementation

Following the development of the scenario forecasts, the next step in the methodology is to evaluate how the airport would cope with and respond to these scenarios. The intention is to test the airport’s current plans and see how the scenarios could impact a range of aspects in airport operations including

- Planning;

- Finance;

- Marketing and communications;

- Operations, security, and safety; and

- Community and stakeholders.

The results of the implementation are summarized in Table 11.

Due to the nature of SFO ADP, in that it postulates two future capacity-constrained activity levels and designs its capital plans from that, the ADP is relatively resilient to faster or slower growth projections. By identifying priority developments, largely on a basis of need in the short term and then on a demand-basis in the long run, the ADP can accommodate changes in traffic growth patterns. The provisions of the airport’s Lease and Use Agreement, specifically the residual rate-setting method with carriers and annual reallocation of gates and terminal facilities that are designed to be common use and nonexclusive, provide the airport with a notable level of risk mitigation and resiliency to cushion financial risks and operational shifts arising from shock events.

Step D: Develop Options for Improved Robustness

With key issues identified in Step C arising from the scenario forecast, the next step in the methodology is to determine what actions could be taken to address these issues and improve the robustness of airport plans. Though this is present as a separate element to Step C, the process of developing these concepts would likely be completed at the same time the impacts are discussed in a holistic process of identifying issues and mitigation strategies that can be developed simultaneously. Below are a series of common actions and themes that relate to one or more of the Step C shock events, discussing both preventive and reactive actions the airport operator may take to improve robustness of the airport.

Modularity in Design and Planning

With respect to the downside scenarios impacting traffic over a longer period of time (loss of a major carrier and United downsizes the SFO hub) incorporating modularity into the design and planning of infrastructure development would help improve the robustness of the airport if traffic demand and capacity fall sharply. Should passenger traffic take a downturn that persistently changes the short-, medium-, or long-term outlook for demand at the airport, incorporating modularity into plans and design can improve the ability of the airport to not overbuild (and overspend) facilities for a demand future that may not be realized or realized much later than expected. Rescaling projects may also be necessary, depending on the shock forecast’s growth potential over the longer-term. In the case of scenario SFO-2, United downsizing its hub, there would likely be a substantive change in the peaking volumes and banking characteristics of demand at the airport. This would require reevaluating processor demands and gate/stand usage, which would then drive decisions on when subsequent phases of processor/terminal development would continue (modularity) but also if those plans need to be revised and rescaled to meet future forecast demand. The airport currently, and throughout its ADP, emphasizes

Table 11. Impacts of the scenario forecasts (SF), SFO.

| Area | SF1-SFO: Loss of Significant Carrier | SF2-SFO: United Downsizes Hub | SF3-SFO: Airfield Damage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning | As the impact is forecast to have a mostly transitory effect on forecast passenger traffic and only a relatively minor, long-term impact, it is likely that the planning objectives for both the Base- and High-Constrained demand levels would not need to be substantially adjusted to accommodate the change in demand. Reaching these demand levels may take longer than anticipated otherwise. As a previously major carrier, its departure would leave terminal facilities available for other airlines. Planned capital improvements to the terminal could be reprioritized to take advantage of underutilized spaces to minimize passenger experience disruption. |

The major reduction in connecting activity and overall passenger traffic at the airport would likely impact the plans for terminal development, namely facilities designed for transfer passengers as well as the terminals and boarding areas [Terminal 3 (T3) E and F and International Terminal Building G] currently used by United Airlines. However, the airport’s Lease and Use Agreement with airlines includes an annual process to reallocate gate and terminal usage, which are assigned on a joint, common, or preferential use agreement. This process would allow incumbents or new entrants to swiftly be reallocated to vacated gates and other terminal facilities and would mitigate many of the challenges that could be faced at an airport with exclusive-use-only gate/terminal use agreements. As T3 facilities are among the oldest at the airport, ADP plans to upgrade T3 and boarding areas E and F would need to be reevaluated to see when those capacity constraints may emerge again given the reduction in operations. There may be opportunities now to accelerate infrastructure upgrades without having such negative impacts on passenger experience as demand for terminal capacity is now lower than forecast. As one of the airport’s major cargo carriers, cargo activity would also be reduced, which may impact planning of those facilities. |

The ADP identified deficiencies in the airport Shoreline Protection System in all of the areas surrounding the eastern ends of Runways 10-28. The ADP has indicated that the deficiencies were identified through a separate evaluation study that made recommendations for addressing these issues. (Johnson et al. 2015) The study indicates that to protect against the impacts of sea level rise and potential storm surges, the airport’s coastal protection system will need improvements with the east end of Runways 10/28 being specific areas of focus given their protrusion into the bay. We note that there do not appear to be major utility corridors or airport facilities within the estimated zone of impact for the shock event, which would mitigate some of the potential damage to only the airside infrastructure and stability of the landfill. |

| Finance | The airport would realize lower-than-forecast revenues in the short term due to the dip in traffic. The long-term traffic impacts are projected to be relatively minor. | A major reduction in operations by the airport’s largest carrier would have direct impacts on airport finances through reduced revenues. However, as impact is projected to be largely on connecting passengers, revenue sources for originating passengers would be relatively less impacted, though there would certainly be a substantial impact on revenues regardless. |

While the traffic loss due to operational restrictions is assumed to be resolved within 1 year, the cost of remediating the airside and landfill could be significant. Insurance liability and coverage would need to be examined, and additional debt may need to be issued to cover the costs to repair. However, existing plans for remediation of taxiway and runway surfaces in the affected area and Runways 10/28 could be accelerated and incorporated into the response work, removing them from future planned capital works. |

| The airport’s residual rate-setting method with air carriers would reduce the financial risk on the airport itself. Fees and charges may need to be revised to meet financial obligations, but the residual method employed at SFO would share the financial risk among airlines and the airport providing mitigation against these types of shock events. | |||

| Marketing and commercial activities | Increased air service development to attract airlines to fill lost service levels. Business-as-usual approach to reallocation of terminal facilities and gates through annual reallocation process under Lease and Use Agreement. |

Air service development activity would need to be increased to find airline(s) to backfill lost capacity and connectivity. Business-as-usual approach to reallocation of terminal facilities and gates through annual reallocation process under Lease and Use Agreement. |

The impact on long-haul operations would likely require negotiations with airlines—both domestic and foreign—and would result in a temporary reduction in overseas traffic impacting various formats of concessions and commercial activities at the airport. |

| Operations, safety, and security | Traffic declines would lead to a reduction in operations but are not expected to impact safety and security. | Significant reduction in capacity and traffic, particularly at specific terminals and airport processors in the first year, would reduce operational demands. As facility reallocation process evolves over the recovery period, potential operational challenges will need to be addressed as carriers may be shuffled across or within the terminals. | Airport operations, particularly airside operations, would be majorly impacted by this shock event. The airport would likely look to past plans regarding how airside operations were reconfigured during runway maintenance to quickly operationalize plans to keep the airport operating at as high of a capacity as possible. |

| Community and stakeholders | Engage with local community and stakeholder groups to identify underserved or unserved markets as part of air service development strategy. | While connecting activity is projected to be reduced, overall global connectivity is assumed to be relatively unaffected. Work with tourism; meetings, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions (MICE); and business stakeholders to identify key routes that may now be underserved or unserved to ensure connectivity to key markets. Noise emissions are likely to be reduced due to corresponding reduction in traffic, which would be seen as beneficial by local community. However, if/when traffic builds again in future, noise issues could become intensified as the community becomes accustomed to a lower volume of aircraft operations. | Airport management may need to reassure stakeholders and the traveling public that the airport is safe and that remediation work will allow for greater resilience against future flooding or water damage. |

modularity and flexibility, which are in many ways enabled through the Lease and Use Agreements provisions for annual gate and terminal facility reallocation based on the need for both incumbent and entrant airlines. Maintaining this flexibility through future Lease and Use Agreement reauthorizations would be critical to building resiliency and risk mitigation from shocks to capacity or carrier makeups.

Trigger Points in Planning

Related to modularity in design is identifying trigger points for planning activities. In the case of unexpected downturns in traffic or growth spurts, developing trigger points on capital development activities provides the opportunity to make investment decisions at the right time. SFO’s ADP Implementation Plan specifically notes that the pace and sequence of planned developments are based on the forecast of traffic growth, among other factors such as finance, construction feasibility, and required sequencing of projects. The ADP notes that “sequencing construction projects solely on demand could result in an excessive number of simultaneous construction projects” beyond what is physically capable at the airport and that development projects are to be viewed as comprehensive improvements in the airport system. While the ADP does not set out specific triggers—be they passenger volumes or other operational metrics—many high-visibility projects such as the Boarding Area H development would be driven by the pace of growth in flights. The ADP does provide a “Lead Time for Decision” metric to indicate how far in advance a go/no-go decision should be made, a practice that provides a concrete expectation on infrastructure planning triggers to manage future development in the event of a major shock to demand or capacity.

Investment in Risk-Mitigation Activities

Taking preemptive actions through planning to mitigate the impacts of climate change could help improve the ability of the airport to face and manage shock events arising from climate change risks, as described in scenario SFO-3. In a similar vein to incorporating earthquake resilience (beyond local building codes) into the design of airport facilities to mitigate negative impacts should a major earthquake occur, taking steps to reduce the airport’s emissions and carbon footprint to lessen the global impact of climate change and its negative consequences may pay dividends in the future. Just as regular maintenance and improvements to the airport’s seawall and dikes manage the risk of flooding or water damage to mitigate the specific risk described in scenario SFO-3, other activities—like reducing carbon emissions and supporting climate change policies—work to reduce the potential risk of climate change-related shocks, like extreme weather or environment events. Since 2011 the airport has published an annual Climate Action Plan to measure emissions and to identify action strategies to reduce airport-controlled emissions and support emission reduction schemes in general, such as supporting sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) development or the transition to zero-emission vehicles (SFO 2021).

Shock Event Response Plans

During the shock event, effective and engaged communication with stakeholders will likely serve to improve the airport’s ability to manage the shock event and build resiliency in recovering traffic (or managing a burst in demand). Stakeholders may need to be reassured of facility safety and operational viability (e.g., in the case of severe airside damage in scenario SFO-3), while marketing and air service development activities with stakeholder airlines, tourism partners, and convention organizers should be reviewed and new strategies formulated should there be major reductions in capacity or the airline mix at the airport (in the case of SFO-1 and SFO-2) to respond to the new market structure.

Shock event response plans must also consider the financial impacts of such shocks and plan for contingencies should the event happen. Major reductions in activity would be met with

decreases in nonaeronautical revenues through reduced passenger volumes. Aeronautical revenues would be unaffected through the airport’s residual rate-setting program, though airline stakeholders would face higher rates for a period of time—assuming costs were fixed. Risk planning and mitigation for the airport’s financial needs is an important part of planning for potential shock events and should consider impacts on long-term obligations like debt servicing and future capital planning priorities as well as immediate concerns over covering operational costs during a period of revenue declines.

Step E: Ongoing Monitoring and Vigilance

The final stage of the methodology is the ongoing monitoring and vigilance of potential shock events and the updating of planning and processes, where necessary. This stage aims to make planning for future shocks, even though they may be low-probability events, an aspect of ongoing vigilance around airport development and planning so the airport can be well-positioned to manage shock events should they occur.

As a general part of risk management and to better incorporate shock events robustness into strategic planning for the airport, production of regular documents that monitor and review risks should be considered. These can take the form of memos or briefing notes and should include tracking existing risks, identifying any shock risks that may be increasing or decreasing in likelihood, and new risks that have been identified. These may be authored by a working group made up of staff from various airport departments and should be presented in a way that is readable and relevant across the airport organization. If the airport already has a regular, ongoing process to monitor and review risks—such as a continually maintained risk register—strategic shock risks should be considered for inclusion in that process.

Where applicable, warning systems may be warranted for specific risks. In this case study, the shock risk of a climate-change-related disaster was examined. Warning systems relating to factors such as sea level rise, an increasing rate of extreme weather events, or global mean temperatures can be macro-level metrics that feed into a shock warning system. These can be complemented by monitoring practices that may already be in place, such as physical sensors or regular observations of airport infrastructure (e.g., the Shoreline Protection System). Not all shock events may have such quantifiable leading indicators or warning signs, but research into the potential risk events and professional knowledge of experts within the airport organization may elucidate metrics or signs that could better warn of shock events and inform how likely a shock event may be to occur.