Incorporating Shock Events into Aviation Demand Forecasting and Airport Planning (2024)

Chapter: 12 Step B: Develop Scenario Forecasts That Incorporate Shock Events

CHAPTER 12

Step B: Develop Scenario Forecasts That Incorporate Shock Events

Shortlisting the Shock Events

As a final part of the initial elicitation of potential shock events, discussed in Step A, or as a follow-up exercise, the participants should be asked to identify the top two to four shock events to be evaluated in more detail. The criteria for this should be those events that are considered most significant and/or most challenging for the airport. The short list of shock events should cover a meaningful range of eventualities and not simply those deemed most likely. The shock events should be chosen because they test as much as possible the robustness of the airport under combinations of different important stressors. The idea is that by focusing on these events, the airport will also be better positioned to handle other events, such as realizing that an approach to mitigating the loss of 50% of traffic can also apply to mitigating the loss of 20%, 30% or 40% of traffic.

The short list of shock events should cover a meaningful range of eventualities, and not simply those deemed most likely. The shock events should be chosen because they test as much as possible the robustness of the airport under combinations of different important stressors.

The number of shock events selected will depend on the time and resources available, but the aim is to have a fairly manageable and digestible list. The scenario planning literature generally recommends no more than four scenarios (including a baseline or business-as-usual scenario) to avoid the exercise becoming overly complex and to maintain the concentration of the participants. In some cases, as few as two scenarios may be sufficient, examining fairly extreme positive and negative shock events. In other cases, there may be a need to examine additional scenarios, such as shock events impacting certain different traffic elements such as domestic versus international, O/D versus connecting, air cargo, etc.

It should be noted that the scope of this research project is on shock events that primarily result in changes to airport traffic, which in turn will drive changes in revenues. Therefore, the scenario forecast should generate information about air traffic, which is the focus of Step B. However, this approach could also be applied to shock events that do not impact traffic, such as real estate or commercial activities.

Further Developing the Scenarios

Having identified a shortlist of shock events for further examination, each can be developed into a storyline as to how the event might develop. The idea is to provide a certain intuitive richness and sufficient detail to allow decision-makers to develop meaningful and realistic ideas about the shock event and how to address it.

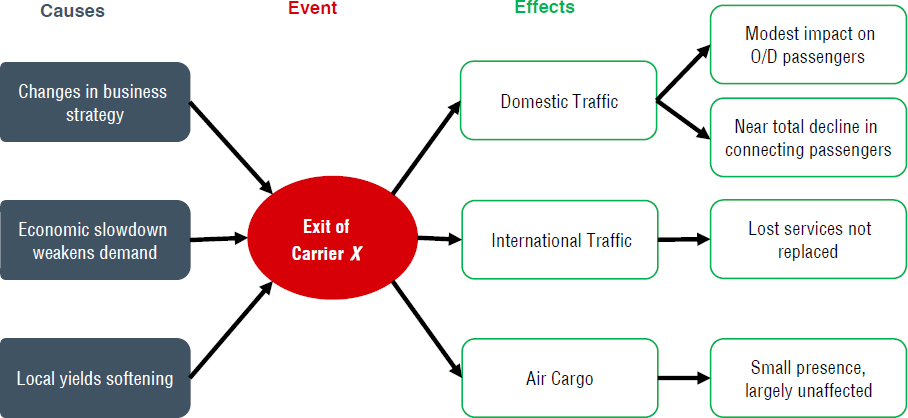

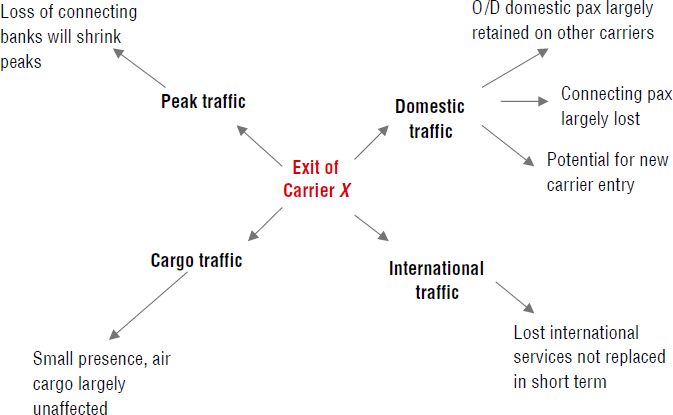

Mapping methodologies can be used to aid this storyline development. One such methodology is bowtie analysis previously described in Part II. This approach maps the factors that

come together to contribute to a shock event and the various consequences after the event. The various consequences can include new risks that can emerge—for example, the airport has less revenue, which leads to a scale back of its development and refurbishment plans and results in a reputation as a dated and crowded airport. This methodology has been used to evaluate accident risks in power generation and aviation safety. Another less structured approach is the use of “mind maps” or flow diagrams, which attempt to capture the effects resulting from a shock event. Examples of a bowtie analysis and a mind map applied to the loss of a carrier are shown in Figure 32 and Figure 33, respectively.

Regardless of the approach used, the aim is to develop a compelling and plausible narrative around the shock event, describe how it comes about, and examine how it impacts traffic at the airport, which informs the scenario forecast and can be concisely explained to the decision-makers through text and diagrams.

Producing Scenario Forecasts

As well as a plausible narrative, quantification is also important to the scenarios. Quantifying the scenarios will enable the communication of shock events impacts to people who need to see numbers, such as finance and planning. As noted by DeAnne Julius, Chief Economist for Shell from 1993 to 1997, “engineers are numbers people, and if you can’t quantify what you are talking about, they tend to dismiss you as interesting (at best) mystics” (Wilkinson and Kupers 2013).

In quantifying the scenario there are numerous considerations.

- Modeling approach. The quantification and modeling of shock events can be an add-on to the existing process of generating air traffic forecasts for planning and management purposes. Existing models can be used to aid in the scenario forecasting process and generation of output. However, the modeling approach could also be conducted as a stand-alone exercise as a deviation from current published forecasts (e.g., the FAA Terminal Area Forecasts) or deviation from current traffic levels.

- Establishing the baseline. As suggested above, the shock event is expected to create a divergence from some sort of business-as-usual baseline. Typically, the baseline will be the forecast used in the planning process (the base or most likely forecast). Alternatively, the shock event could simply be analyzed against current traffic volumes.

- Timing of the event. The timing of a shock event is impossible to predict, so an assumption about when the event occurs will need to be made. This could be now (especially if using current volumes as the baseline) or sometime in the short- to medium-term. To some degree, the timing will depend on the nature of the event. For example, the impact of some technological change may be expected to be in the medium-term given the need for product research and testing. However, as a general rule, the event should be shown occurring in the short- to medium-term. Showing an event some 10 to 15 years in the future could make it difficult for decision-makers to determine what actions should be taken now and may also give the impression that dealing with the event can be put off until later.

- Magnitude of the impact. In some cases, the impact on traffic volumes might be determined by examining past events as a guideline to severity and duration. But in doing so, the analyst needs to give thought to whether they need to go beyond historical precedents. As previously noted, the impact of the 2003 SARS pandemic was a weak guide to the impact of COVID-19. The brainstorming in Step A may provide information on the anticipated impact. For some events, specific analysis should be undertaken to determine magnitude. For example, if considering the loss of a major carrier, data will generally be available on the passengers and cargo carried and routes operated by that carrier. A route and network model can be used to model the potential entry of a replacement carrier(s). This modeling will need to consider the frequency and routes operated, the aircraft type(s) used (past and future), and the load factor required. Some events may impact certain traffic segments more than others (e.g., domestic versus international, leisure versus business destinations/origins); the analysis could also capture this.

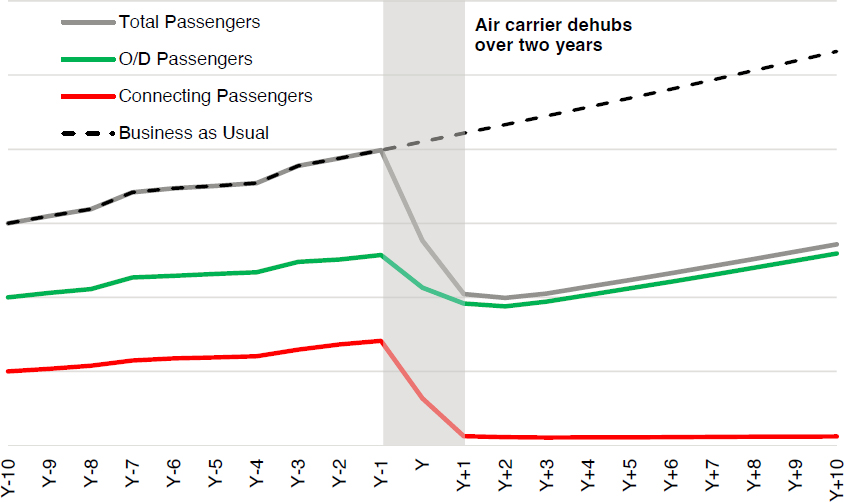

- Duration and aftermath. The duration of the event may vary from almost immediate, such as a terrorist attack or natural disaster, to unfolding over months or years, such as an airline gradually dehubbing or climate change effects. Again, past examples can be used as a guide, but they should not blinker the analyst to other possibilities. The aftermath should also be modeled using suitable logic, such as the potential traffic recovery following a shock decline in traffic and whether there is a possible reversion to the long-term trend after a positive event. Consideration should be given to whether there will be a full recovery of traffic if it is a negative event and over what timeline. Again, the duration and recovery may vary for different traffic segments.

- Level of detail. The level of detail will depend on the resources available (including the time commitment of participants) and the requirements of the project. To evaluate the financial implications of the event, information on the impacts on annual domestic and international passenger and aircraft operations may be necessary. For planning purposes, the impact on peak-hour traffic may also need to be considered. If using the airport’s existing forecasting model, many of these outputs could be generated through that model.

An example scenario forecast is provided in Figure 34. This shows a fictional airport that experiences the dehubbing and exit of a network airline over a period of 2 years. Events like this have been experienced at airports such as STL, LAS (US Airways night hub), and PIT. In the example, the carrier accounts for 50% of traffic at the airport before the event. As the only hub carrier at the airport, the exit results in the loss of 90% of connecting passenger traffic, compared with a loss of only 25% of O/D traffic (some domestic routes and most international routes are lost). The event results in a 50% decline in passenger traffic after 2 years relative to preevent levels and a 54% decline relative to the business-as-usual forecast made before the event. O/D traffic takes 10 years to recover to preevent levels, while connecting traffic remains depressed. After 10 years, total traffic volumes are at 32% below preevent levels and 49% below the business-as-usual forecast. Additional detail of traffic by segment, aircraft operations, and peak can also be generated from this forecast.

Scenario forecasts do not necessarily produce more accurate forecasts but challenge planners and decision-makers as to how these outcomes can be managed and mitigated in the airport planning.

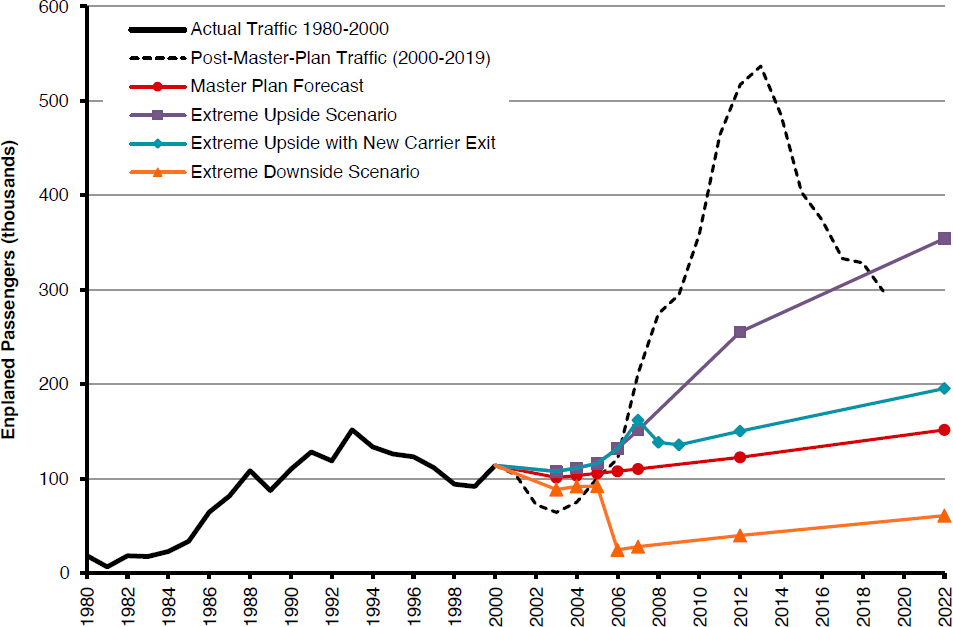

Another example of the use of scenario forecasts is provided in Figure 35, taken from ACRP Report 76 (Kincaid et al. 2012). In this report, scenario forecasts for Bellingham International Airport (BLI) were generated based on the airport’s circumstances in 2003 and 2004 when the airport was developing its master plan and before the entry of Allegiant Air, which caused traffic to surge (BLI is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5). The exercise was undertaken in 2011 by the ACRP research team (not airport management) and applied to historical data as a test case. In addition to the master plan forecast, three scenario forecasts were generated in the ACRP exercise:

- Extreme downside – exit of some existing carriers and weakened growth;

- Extreme upside – rapid growth associated with the entry of a new LCC; and

- Extreme upside with new carrier exit – initial rapid growth associated with entry of a new LCC, but after 2 years the carrier scales back operations and leaves the market.

These scenario forecasts provided a wide range of outcomes with the extreme downside forecast 60% lower than the master plan forecast, and the extreme upside 2.3 times the master plan forecast. Also shown in Figure 35 are actual passenger volumes (the dotted black line). As can be seen, volumes initially exceeded the extreme upside but reduced as Allegiant scaled back services (as described in the Task 2 write-up).

It should be noted that the intention with scenario forecasts is not to necessarily produce more accurate forecasts but to challenge planners and decision-makers as to how these outcomes can be managed and mitigated in airport planning.

More Advanced Methodologies

Part II discussed the use of Monte Carlo simulation in air traffic forecasting. Monte Carlo simulation makes use of randomization and probability statistics to generate a wider range of possible traffic outcomes than a conventional forecast. As previously noted, shock events can be included in Monte Carlo simulation, but the perceived low-probability nature of shock events means that their impact may not be prominent in the output, and this could understate the significant and potentially profound effects of certain shock events.

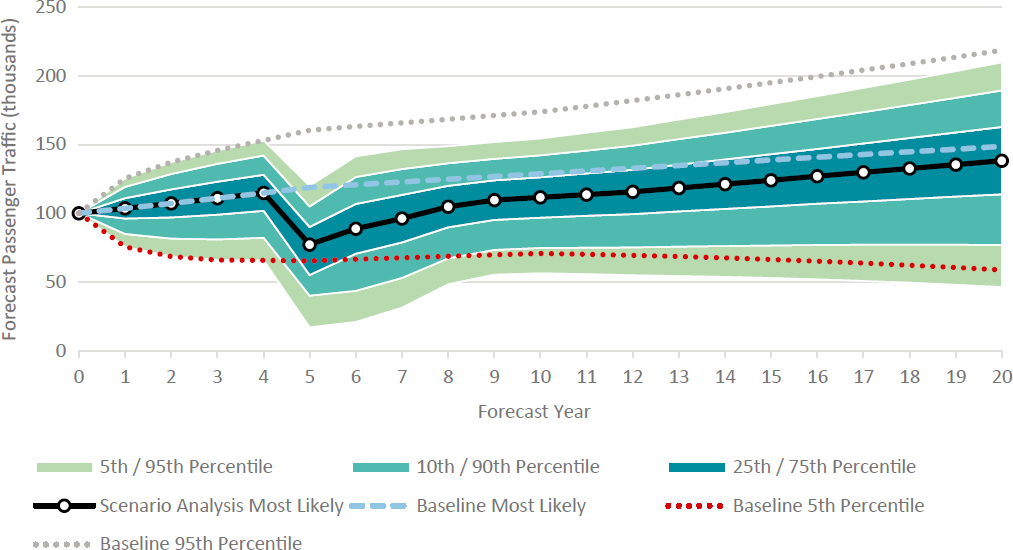

However, there are ways to make the impacts of shock events more explicit in a Monte Carlo simulation. It involves “locking in” the event of interest so that the model always triggers the event at a given time. For example, the probability of a terrorist attack would be set at 100% in a given year. All other variables and parameters are randomized and so vary around this shock event. This is illustrated in Figure 36. The shock event is always triggered in Year 5 of the forecast,

although its magnitude is still randomized. The impact on traffic is shown as a range around the shock event—the extent of traffic decline and recovery being a function of these other factors as well as the shock event. Thus, scenario forecasts can be generated within the Monte Carlo analysis while still incorporating other uncertainties.

Further details on this approach are provided in Appendix C.

Simplifying the Process

As noted previously, the degree of complexity and detail that goes into the scenario forecasts will depend on the time and resources available and the requirements of the project. The sections above describe a number of methods for developing and modeling scenario forecasts with varying degrees of complexity. However, simple but still informative forecasts can be developed without the need for advanced methodologies. The type of forecast shown in Figure 34 can be generated using a small set of spreadsheet calculations, with the results presented in chart or table format. Similarly, if a small airport is considering a simple shock event involving the loss of half of its traffic, then a forecast based on a 50% decline in current traffic levels may be sufficient to stimulate thinking about the implications of such an event.

Outcome

This step will generate plausible and reasoned forecasts of traffic for a shortlist of critical scenarios with sufficient detail to allow decision-makers to fully evaluate the implications of these scenarios for the airport business. Although the examples above focus on passenger traffic, the scenario forecasts should give information on all relevant traffic elements, such as cargo and GA.