Incorporating Shock Events into Aviation Demand Forecasting and Airport Planning (2024)

Chapter: 3 Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the U.S. Aviation System

CHAPTER 3

Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the U.S. Aviation System

Timeline of the Pandemic and Government Regulation

The key milestones in the development of the COVID-19 pandemic, the development of vaccines, and the government’s (U.S. federal and state) response to the pandemic are summarized in Table 1. Milestones that directly affected travel and the travel industry are highlighted in green.

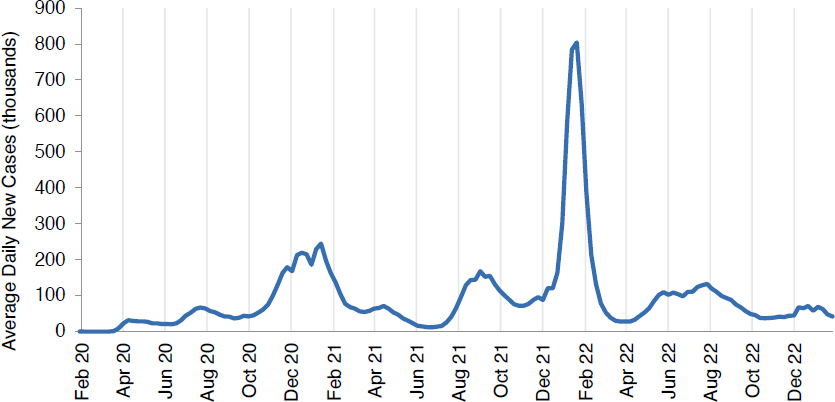

Figure 3 shows the development of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States in terms of the number of new cases reported daily. Daily cases reached around 31,000 (weekly average) in early April 2020 and then flattened with the imposition of stay-at-home orders. With the removal of these orders and relaxation of other restrictions in summer 2020, cases started to rise again. Cases rose rapidly in winter 2020/2021, reaching 245,000 average daily cases per week due to the population being in closer proximity indoors and the emergence of more contagious variants of the virus, notably the Delta variant (the first U.S. case was recorded on February 23, 2021). The imposition of further restrictions along with the vaccine rollout led to cases falling to less than 12,000 average daily cases in June 2021. Cases rose again during summer 2021 as most remaining restrictions were lifted, reaching over 165,000 average daily cases in August, after which cases started to decline. The Omicron variant (first detected in the United States on December 1, 2021) led to a rapid surge in new cases, peaking at over 800,000 average new daily cases in January 2022. The Omicron variant was generally considered more transmissible but less severe than previous variants. Cases declined later in the year due to vaccines and natural immunity buildup, averaging around 50,000 to 70,000 new daily cases in the latter half of 2022.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on U.S. Air Passenger Traffic

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the single largest downturn in global aviation activity in the history of modern aviation. Air passenger traffic across the United States, as with nearly all other nations, was most drastically and negatively impacted after the initial onset of the pandemic in 2020.

By the end of 2020, monthly national passenger volumes had recovered to only 37% of prepandemic levels, and traffic for the entire year was down 61% relative to 2019.

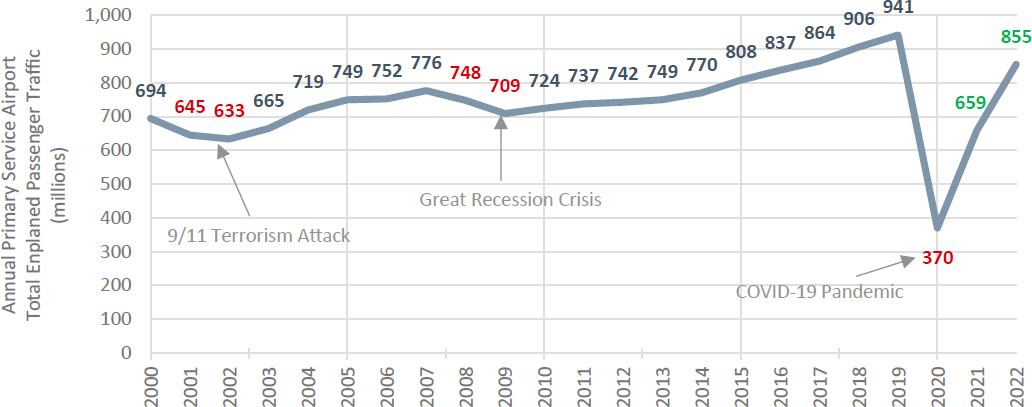

The pandemic-driven drop in total passenger enplanements in 2020 and 2021 is compared against the longer timeline of annual traffic since 2000 in Figure 4. (Year-over-year declines are noted in red; green figures indicate periods of significant growth.) Prior events driving annual declines in passenger volumes include the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attack and the U.S. recession in 2001, followed by the Great Recession of 2008–2009. The impacts of these events, which resulted in single-digit percentage declines in annual passengers are significantly smaller than that of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1. Pandemic timeline.

| Date | Milestone |

|---|---|

| December 2019 | First reports of a novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. |

| January 9, 2020 | World Health Organization (WHO) releases a statement regarding the identification of a new virus. |

| January 20, 2020 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) begins screening for the virus at John F. Kennedy International Airport, San Francisco International Airport, and Los Angeles International Airport (the airports where most passengers to/from Wuhan connect). |

| January 21, 2020 | First U.S. coronavirus case is reported in Washington State. |

| January 30, 2020 | WHO declares a global public health emergency. |

| January 31, 2020 | United States bans travel from China for non-U.S. citizens. |

| February 6, 2020 | First COVID-19-related death in the United States. |

| February 11, 2020 | WHO officially names the disease caused by the new coronavirus COVID-19. |

| March 11, 2020 | WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. |

| March 13, 2020 | United States declares COVID-19 a national emergency. Travel ban on non-U.S. citizens traveling from Europe goes into effect. |

| March 19, 2020 | U.S. State Department issues a Level 4 travel advisory: U.S. citizens should not travel abroad due to the global impact of COVID-19. |

| March 19, 2020 | California is the first state to issue a stay-at-home order requiring all but essential workers to work from home and avoid nonessential travel (Puerto Rico issued an order on March 15). A total of 40 U.S. states issued stay-at-home orders during late March and early April (the remaining 10 states issued advisories). |

| March 20, 2020 | U.S. closes land borders with Canada and Mexico to all nonessential travel. |

| March 27, 2020 | The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act is signed into law, providing $2.2 trillion in aid to the U.S. economy. |

| April 3, 2020 | CDC recommends individuals wear face masks in public spaces to reduce the spread of COVID-19. |

| April 26, 2020 | Colorado and Montana become the first states to lift stay-at-home orders. |

| June 11, 2020 | New Hampshire becomes the final state to remove stay-at-home orders. |

| July 27, 2020 | Moderna and Pfizer begin Phase 3 (final stage) clinical trials of their COVID-19 vaccines. |

| December 11, 2020 | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine receives emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for individuals 16 years and older. |

| December 14, 2020 | First doses of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine begin to be distributed in the United States. |

| December 18, 2020 | FDA authorizes the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use in individuals 16 years and older. |

| December 27, 2020 | The Consolidated Appropriations Act is signed into law, providing $900 billion in stimulus relief to facilitate national economic recovery. |

| April 30, 2021 | By the end of April, 46% of the eligible population had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. |

| March 11, 2021 | American Rescue Plan Act is signed into law, providing $1.9 trillion in stimulus and support to the U.S. economy. |

| May 20, 2021 | Lifting of restrictions on businesses and public spaces underway in all states that had stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders. |

| August 2, 2021 | United States reaches 70% of the eligible population vaccinated with at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. |

| Date | Milestone |

|---|---|

| August 23, 2021 | Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine becomes the first COVID-19 vaccine to receive full approval from the FDA. |

| September 9, 2021 | New executive order requires federal employees and federal contractors to be fully vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccines. |

| October 31, 2021 | By the end of October, 78% of the eligible population had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. |

| November 8, 2021 | United States reopens borders to all foreign national travelers provided they are fully vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine, with limited exceptions. Land borders with Canada and Mexico reopen to nonessential travel. |

| November 29, 2021 | Entry of non-U.S. citizens from eight southern African countries was suspended due to concerns over the new Omicron variant originating from that region. |

| January 31, 2022 | FDA approves a second COVID-19 vaccine (the Moderna vaccine, marketed as Spikevax). |

| February 25, 2022 | CDC updates its guidance regarding mask-wearing based on risk. |

| June 12, 2022 | The requirement for a negative COVID-19 test before boarding a flight to the United States is rescinded, regardless of vaccination status. |

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Defense 2023; AJMC Staff 2021; Wu et al. 2020; The New York Times 2021; Elassar 2020.

By the end of 2020, monthly national passenger volumes had recovered to only 37% of prepandemic levels, and traffic for the entire year was down 61% relative to 2019 (U.S. DOT, n.d.).

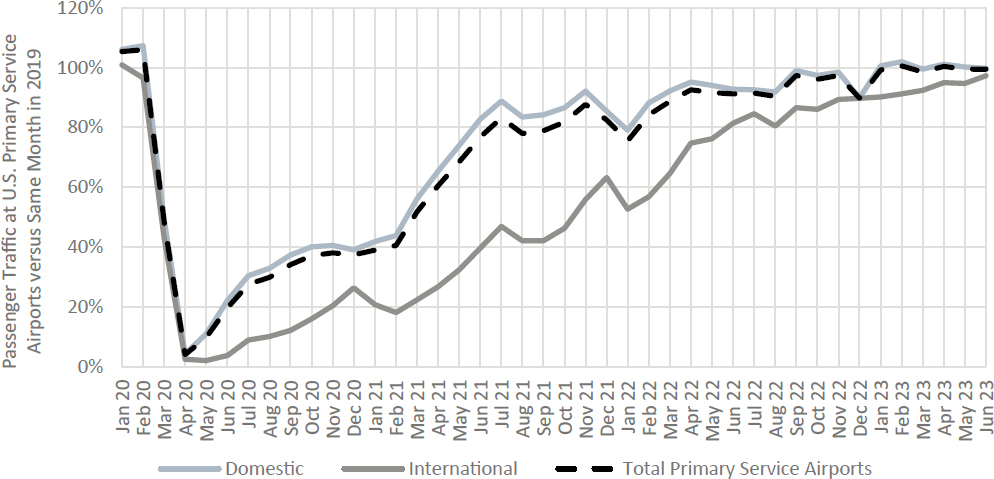

U.S. air passenger traffic partially recovered in 2021, reaching 70% of 2019 annual levels, due to the removal of some domestic travel restrictions and the deployment of the first vaccines across the United States. As shown in Figure 5, by summer 2021, monthly passenger traffic had increased to between 80 and 90% of prepandemic 2019 levels and generally maintained a similar level of recovery in most months up through the first half of 2022. By the second half of 2022 and into 2023, total system traffic was approaching 100% recovery to 2019 levels, though monthly international passenger recovery remained below domestic but was trending toward a full recovery in summer 2023.

Figure 3. Average daily new COVID-19 cases per week in the United States, February 2020 through December 2022 (as sourced from the CDC).

The initial rebound in passenger traffic throughout 2020 and 2021 was driven by domestic travel, due to relaxing many state-level lockdowns and the implementation of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to support the U.S. aviation industry. Conversely, international traffic remained hampered by federal government restrictions regarding border crossings along with restrictions imposed by foreign countries. By the end of 2020, domestic traffic had recovered to 39% of 2019 levels, while international traffic was at 26%. Further relaxation of restrictions and the mass vaccination of U.S. citizens and residents beginning in early 2021 then led to a major uptick in domestic air travel starting in March 2021, with domestic traffic reaching 89% of 2019 levels by July 2021 compared with just 47% for international traffic. The gradual growth of international traffic was more heavily oriented to destinations in the Caribbean and Latin America with many pre-COVID-19 top destination countries (e.g., Canada, United Kingdom, Japan, China) seeing

As of June 2022, the recovery of international passenger traffic nationwide has lagged behind domestic traffic by roughly one year.

limited recovery due to travel restrictions in those countries on nonessential travel. Monthly international traffic experienced a stronger recovery from the start of 2022, although exceeding 80% of 2019 levels only by June 2022, roughly 1 year later than when domestic traffic had reached the same recovery point. International passenger volumes saw steady but slowing recovery rates in the latter half of 2022 and into 2023 and were approaching 100% recovery at a monthly level by the summer of 2023.

Impacts by Airport Size and Type

Across various types of airports, the recovery of traffic has remained largely consistent. Airport types are defined by the National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS), which includes 396 Primary Service Airports (FAA 2020). These Primary Service Airports, which process nearly all of the commercial passenger traffic in the United States, are categorized into the following types:

-

Large hubs: Airports that receive more than 1% of annual U.S. enplanements. This category comprises major carrier hubs, international gateways, and large origin/destination (O/D) airports such as

- Los Angeles International Airport (LAX),

- San Francisco International Airport (SFO),

- John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK),

- Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL),

- Denver International Airport (DEN),

- Harry Reid International Airport (LAS), and

- Daniel K. Inouye International Airport (HNL).

-

Medium hubs: Airports that receive 0.25% to 1% of annual U.S. enplanements. This category includes airline regional hubs, focus cities, and larger metropolitan area airports such as

- San Francisco Bay Oakland International Airport (OAK),

- Raleigh-Durham International Airport (RDU),

- Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport (MSY), and

- Nashville International Airport (BNA).

-

Small hubs: Airports that receive 0.05% to 0.25% of annual U.S. enplanements. This category accounted for 9% of passenger traffic in 2019 and comprises spoke airports to major hubs, medium-sized metropolitan areas such as

- Memphis International Airport (MEM),

- Will Rogers World Airport (OKC),

- Reno-Tahoe International Airport (RNO), and

- Boise Airport (BOI).

- Nonhubs: Airports that process more than 10,000 annual passengers but fewer than 0.05% of annual system traffic (approximately 500,000 passengers in 2019). This category of 266 airports accounted for less than 4% of total NPIAS passengers in 2019.

The 30 large hub airports accounted for 71% of total NPIAS traffic in 2019, while medium hub airports accounted for a further 17%. Therefore, these two airport categories represent most of the commercial passenger traffic in the United States.

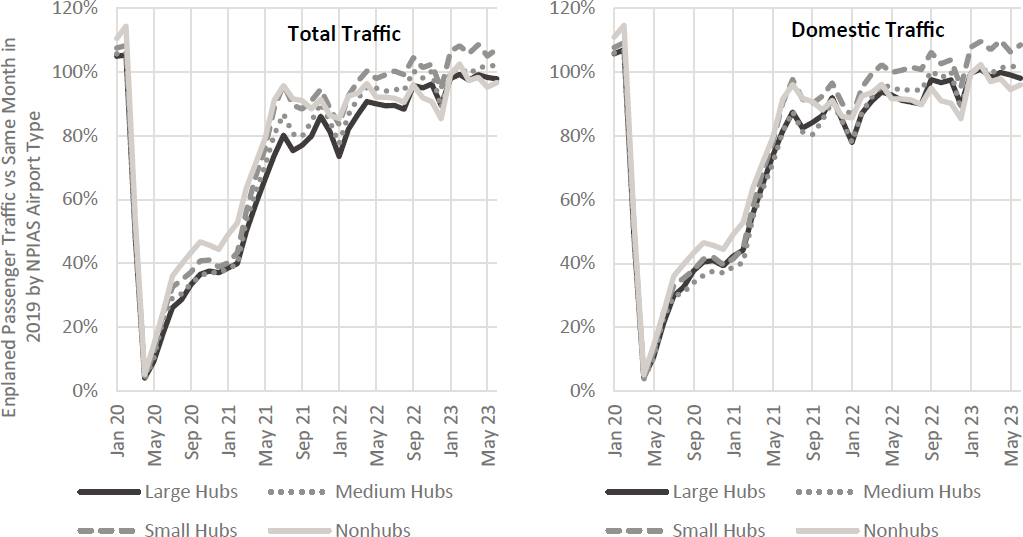

Figure 6 shows the recovery of passenger traffic, carried on both U.S. and foreign carriers, at the four NPIAS airport types relative to the same month in 2019. All Primary Service Airport types experienced very similar declines and recoveries in passenger traffic. Smaller airports, such as the small hub and nonhub airports, have fared slightly better in the recovery than the bigger large and medium hubs. This can be attributed to much lower exposure to international traffic

at these airports, with nonhub airports recovering domestic traffic slightly better than other airport categories. This may be due to the lower level of traffic and services at these smaller airports as well as the impacts of government support mechanisms such as the Essential Air Services (EAS) program and pandemic-related relief programs (discussed later in this chapter).

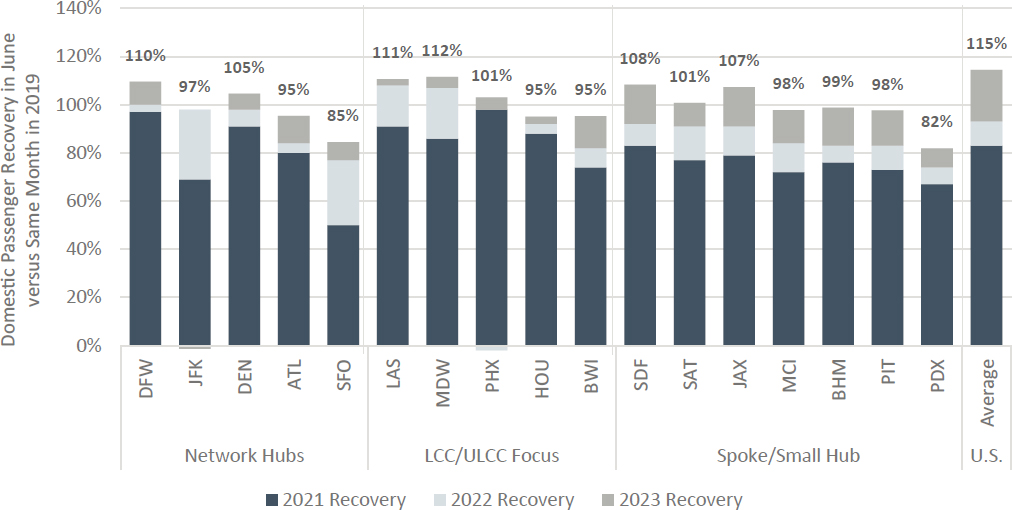

Passenger traffic recovery at individual U.S. airports has also depended on the types of airlines served and each airport’s role in those airlines’ networks. Figure 7 shows the extent of domestic passenger volume recoveries in June 2021, 2022, and 2023 versus June 2019 at selected U.S. Primary Service Airports with various roles and network structures. These examples are grouped into three categories: major network hubs; airports that are primarily focused on service by low-cost carrier (LCC) and ULCC airlines; and spoke airports that are primarily connected to larger network hubs or are primarily O/D airports. These categories are not always mutually exclusive (e.g., DEN is displayed as a large hub airport given its relationship with United, but it also serves as a hub/focus city for LCCs Frontier and Southwest Airlines); however, the analysis is indicative of key trends by different network types.

Airports whose capacity was more oriented to LCC and ULCC traffic initially fared the best in their recovery to prepandemic levels, due to focus on leisure, VFR, and domestic point-to-point travel.

Up until June 2021, airports whose capacities were more oriented to LCC and ULCC traffic generally fared the best in their recovery to prepandemic levels. With travel demand in 2021 being dominated by leisure and “visiting friends and relatives” (VFR) travel, ULCCs have had the opportunity to serve that pent-up demand without the challenges some network carriers may have faced due to the slower recovery of business and international passenger demand. Network hubs experienced further traffic recovery up through June 2022, but there was considerable variation due to exposure to slower-recovering international markets. LCC- and ULCC-oriented airports experienced further recovery up to June 2022, with some exceeding 2019 levels. By mid-2023, the trends seen in 2022 had largely continued with some network hub airports, particularly those with a large proportion of international service, remaining at a lower level of recovery than some smaller airports.

Figure 7. Domestic passenger recovery at selected U.S. airports by network structure, June 2021, 2022, and 2023 versus June 2019 (U.S. DOT, n.d.).

Finally, spoke (nonhub) airports have generally recovered close to but still below the national average traffic due to a variety of outcomes from the pandemic. Among these outcomes are financial strains, which have changed the relationships between legacy network carriers and their regional affiliates, with some regional airlines, such as Trans State Airlines and Compass Airlines, ceasing operations altogether. To curb costs, airlines have also accelerated the retirement of smaller 50-seat regional jets, a shift that predominantly impacts smaller communities and spoke airports for markets that may not generate sufficient demand to fill mainline narrow-body aircraft at a frequency to provide adequate connectivity throughout the network.

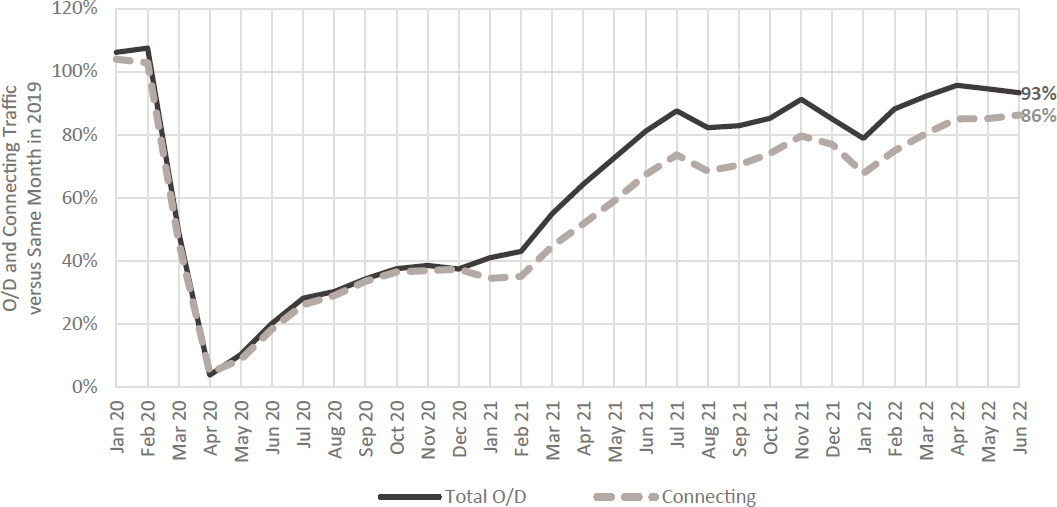

While airline networks and services shifted in many ways throughout the pandemic, the overall impact on O/D versus connecting (transit and transfer) traffic nationwide has followed similar trajectories. Both O/D and connecting passengers declined by 96% compared to 2019 levels in April 2020, which was the most restricted month for air travel during the pandemic, as shown in Figure 8. By June 2021 and 2022, O/D traffic at U.S. Primary Service Airports had recovered to 81% and 93%, respectively. At the same time, connecting passengers had recovered to 57% in mid-2021 and were at 86% of 2019 values in June 2022. The gap in recovery between O/D and connecting passenger volumes is attributed to two factors. First, with international traffic having only recovered to much lower levels than domestic, there is a portion of connecting traffic that is yet to recover in the domestic-to-international connections, primarily at large hub gateway airports. Second, there has been a greater recovery in LCC and ULCC traffic during the pandemic, which is primarily point-to-point versus connecting itineraries. Both of these effects point to a relatively lower level of connecting traffic among total enplanements in the United States. However, the difference between the two categories of traffic is fairly small, and there is no evidence that carriers significantly changed the mix of O/D and connecting traffic in the operations, even as traffic volumes declined.

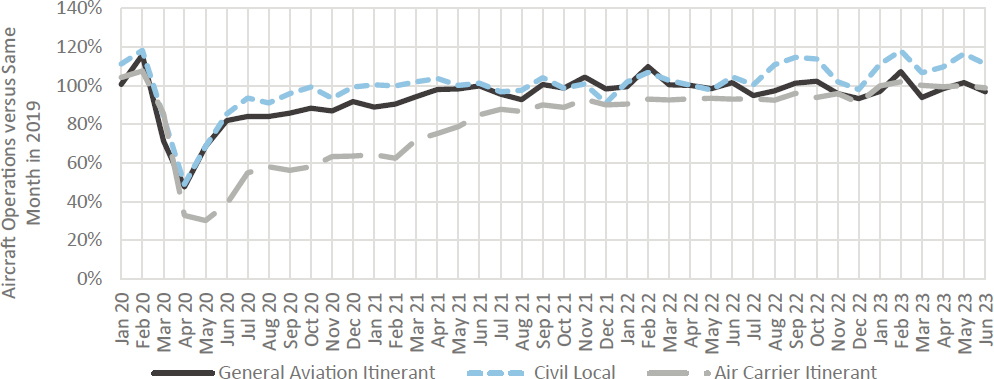

Impacts on Aircraft Operations

Compared to commercial passenger traffic, commercial aircraft operations at U.S. Primary Service Airports experienced a smaller reduction in activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. As shown in Figure 9, total commercial aircraft operations dipped to a low of just 33% of 2019 monthly levels in April 2020 versus total passenger traffic dropping to a low of 4% of 2019 traffic in April 2020. The smaller dip in operations throughout 2020 and 2021 is attributable to a number of factors, but it is primarily attributed to the effect of government funding programs, which required airlines to maintain minimum levels of activity. This led to higher levels of aircraft movements relative to passenger traffic and reduced load factors throughout the pandemic. The relatively lower reduction in aircraft activity compared to passenger traffic also likely assisted airports’ finances through this time by inducing a relatively smaller reduction in aeronautical revenues (i.e., landing fees) compared to passenger-related revenues (i.e., concession revenues), as discussed in a later section. However, some airports indicated that this reduced level of aircraft activity was increasingly concentrated in peak periods—particularly in 2020—placing peak demands for gates and other airport infrastructure at levels closer to prepandemic while remaining very quiet during off-peak periods. The recovery of commercial aircraft operations plateaued around summer 2021 and has remained around 90% up to and through June of 2023. International operations, after seeing a cut back in early 2022, likely associated with the Delta and Omicron waves leading to renewed health restrictions in some countries, have seen a fairly steady increase now nearly matching domestic’s recovery by mid-2023.

Commercial aircraft operations did not decline to the same extent as passengers due in part to government support to airlines.

Impacts on Air Cargo and General Aviation

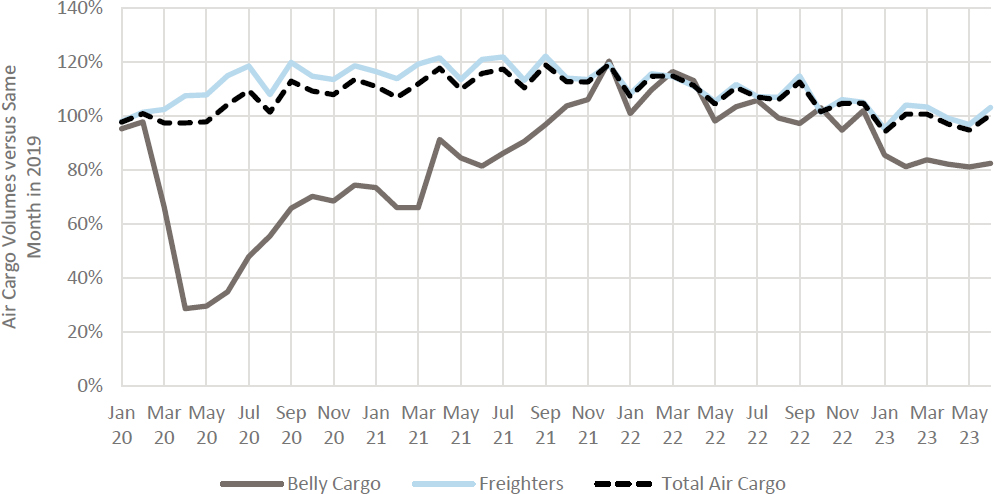

While commercial passenger service experienced unprecedented declines during the pandemic, air cargo activity grew, with national tonnage increasing throughout the onset of the pandemic for several reasons including 1) higher e-commerce and integrator usage as consumers

shifted to online shopping; 2) greater substitution toward air service as a more reliable transportation method for shippers in the wake of congestion and rising prices in the maritime sector; and 3) emergency use of air service as the fastest shipping method for transporting medical supplies, devices, and eventually vaccines to combat the pandemic. Figure 10 shows air cargo volumes at U.S. airports during the COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in January 2020, relative to the same month in 2019. Total tonnage—including both freight

While commercial passenger service experienced unprecedented declines during the pandemic, air cargo activity grew.

Figure 10. Air cargo weight (pounds) at U.S. airports versus the same month in 2019, January 2020 to June 2023 (U.S. DOT, n.d.).

and mail—saw only a very minor dip below 2019 levels during the early stages of the pandemic in the first two quarters of 2020. From mid-2020 to late 2022, total air cargo volumes remained above 2019 levels. The drawing back of cargo volumes in 2023 was likely reflective of the lessening of global supply chain issues, particularly in the maritime shipping sector, which supported some of the rapid growth in air cargo in 2020 and 2021. In many cases, air cargo movements increased during the pandemic, with a greater share of volume carried on freighter aircraft or converted passenger aircraft (“preighters”) to meet the rising demand for air service and to offset the loss of considerable belly capacity due to passenger service reductions by commercial airlines.

While total air cargo volumes across U.S. airports increased in total in 2020 and 2021 compared to 2019, not all airports experienced equal growth. Cargo tonnage at large hub airports declined by 3.5% in 2020 compared to 2019 as a result of the reduction in passenger activity, particularly in international passenger services, which normally carry cargo in the belly hold of wide-body aircraft. As large passenger hub airports do not typically receive significant amounts of freighter traffic (due to capacity and/or slot restrictions), the reduction in passenger services and belly cargo led to a reduction in cargo at these airport types as a group. Medium hub airports saw the largest growth in cargo activity in 2020 at 14% due to growth in cargo activity at the nation’s larger cargo airports, which are medium hubs in terms of passengers (e.g., Anchorage, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Ontario). Small hub airports saw a 5% gain in cargo volumes, though that growth was driven almost entirely by growth in cargo at Memphis (MEM) and Louisville (SDF), which are global hubs for FedEx and United Parcel Service, respectively.

General aviation (GA) was less negatively impacted by the pandemic and recovered more quickly relative to commercial passenger operations. As depicted in Figure 11, itinerant GA and local civil operations at U.S. airports in April 2020, declined to 45% of the April 2019 level (versus a 67% decline for commercial passenger aircraft). However, by summer 2020, GA and local civil operations had recovered to 90% or higher (compared with less than 60% for commercial passengers). By summer 2021, activity levels were back at or above 2019 levels. The relatively modest decrease in GA and civil local operations can largely be attributed to private and business aviation being utilized as an alternative to commercial flying during a period when commercial air travel was reduced and restricted due to health measures. An increase in local operations versus pre-COVID levels in 2022 and 2023 may be related to increased training activity, potentially as a response to demand for commercial pilots and re-training following airline furloughs during 2020–21.

Aeronautical revenues declined less than nonaeronautical revenues (−11% versus −32% for all airports).

Airport Financial and Business Impacts

With sustained reductions in commercial passenger traffic, airports faced a substantial financial downturn. To provide a national assessment of the impact of the pandemic on airport financials, analysis was conducted on FAA Certification Activity Tracking System (CATS) Report 127 data, an online source of financial data for airports, both individual and aggregate (FAA, n.d.-b). There are differences in how individual airports report their financials, including which financial year they report—some use a calendar year while others use fiscal years ending April 30, June 30, or September 30. Nevertheless, FAA CATS provides a useful dataset for observing the overall trends in airport financials.

Figure 12 presents year-over-year trends for U.S. airport aeronautical revenues, nonaeronautical revenues (parking, car rental, food and beverage, retail, etc.), and total revenues for fiscal years (FY) 2019 and 2020 [operational revenues only, i.e., excluding nonoperational revenue such as Passenger Facility Charges (PFCs), interest income, or grant receipts]. FY 2019 is a prepandemic year, and depending on the fiscal year calendar used by individual airports, FY 2020 includes a portion of the year that is prepandemic and a portion of the year during the pandemic.

Across all airports, total revenues declined by 19% versus a 40% drop in passengers in the relevant fiscal year (the reported decline in passengers differs from the figure previously reported due to the mixing of fiscal years in the data). These equate to an operating revenue decline of $4.7 billion across all airports (from $24.7 billion in FY 2019 to $20.0 billion in FY 2020). Large hub airports experienced the greatest decline in revenues due in part to their greater exposure to international traffic, which has been slower to recover. Large hub airports accounted for 76% of total airport revenue decline (large hubs accounted for 71% of passenger traffic prepandemic). In all cases, aeronautical revenues declined less than nonaeronautical revenues (−11% versus −32% for all airports). Aeronautical revenues are more linked to aircraft operations (and landed weight) which, as previously discussed, did not decline to the same extent as passengers. Nonaeronautical revenues are more directly related to passenger volumes. Airports either experienced a decline in customers at their nonaeronautical businesses or received reduced payments from concessionaires that depend on passenger volumes (in many cases, the airports provided relief to these concessionaires). The airport financials for FY 2021 in the FAA CATS Report 127

![Airport operational revenue year-over-year trend by hub size, FY2019 and FY2020 [InterVISTAS’s analysis of FAA CATS Report 127 (FAA, n.d.-b)]](https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/27987/assets/images/img-30-1.jpg)

showed a similar decline in revenues, with total U.S. aeronautical revenues down by 9% relative to FY 2019 and nonaeronautical revenues down by 35% (FAA, n.d.-b). The similarity in results is due in part to the mixing of fiscal years (e.g., an airport using a fiscal year starting from April experienced the initial declines in FY 2021, while an airport using a fiscal year starting from January or September experienced the initial declines in FY 2020).

Government Support

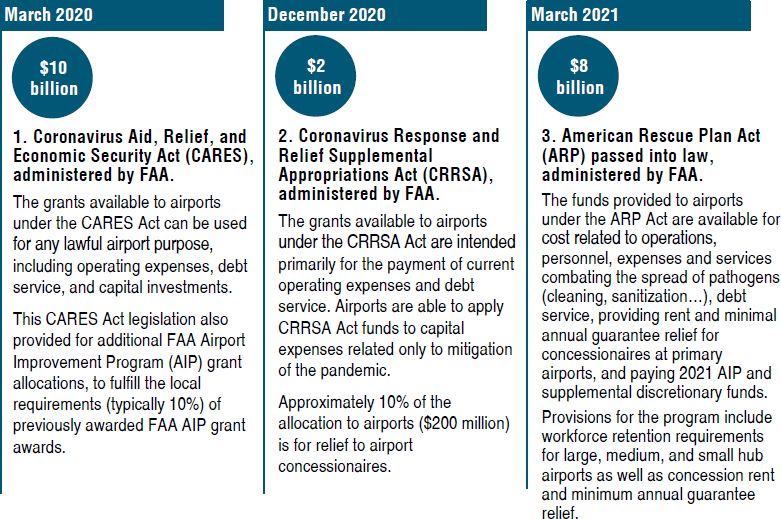

In response to the financial and economic risks posed by the pandemic, the federal government introduced several support programs providing funding for the aviation industry, including airports. These programs were the CARES Act in March 2020; the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations (CRRSA) Act in December 2020; and the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act in March 2021. The CARES, CRRSA, and ARP Acts collectively allocated approximately $20 billion in support for airports and their concessionaires over the course of several years, as summarized in Figure 13.

Aside from direct grants, airports also benefited from the support provided to U.S. airlines. For example, the CARES Act provided support totaling $62 billion for airlines and related contractors. The aid to airlines was split with approximately 50% going to direct aid to pay salaries and benefits and 50% going into loans and loan guarantees for general business purposes. There were various conditions and restrictions for accepting this aid, which did influence the degree to which individual airlines participated in the aid program. The conditions most important for operations at airports included no involuntary staff furloughs, maintenance of employment at 90% levels, and maintenance of minimum air service levels. As noted previously, aircraft operations did not decline to the same extent as passenger numbers, which was due in part to these conditions. The airline support in the CARES Act and subsequent bills also avoided the bankruptcy of any major U.S. airlines, which could have impacted airport traffic in the short and long term.

In many cases, U.S. airports allocated CARES Act funds toward their airline cost centers to reduce or maintain airline rates and charges. Measures targeting concessionaires, terminal service providers, and ground transportation operators included the waiver of minimum annual guaranteed payments, payment deferral, and rent relief. The different federal aid packages have been used to cover operating expenses, debt service requirements through the expected recovery period, and to maintain or reduce airline rates and charges. Many airports did not fully utilize funds in fiscal years 2020 and 2021, with funding available for future years. Airports nationwide drew on governmental support, in part to help offset these revenue losses. The CATS Report 127 data show that airports received grants totaling $5.5 billion in FY 2020 and $6.8 billion in FY 2021, an increase of 135% and 193%, respectively, relative to FY 2019 ($2.3 billion) (FAA, n.d.-b). Much of this increase can be attributed to support provided by the CARES Act, although it likely also includes other grants unrelated to the pandemic. Figure 14 compares the level of support provided to airports relative to revenue losses, calculated as the increase in grant receipts in FY 2020 and FY 2021 relative to FY 2019, divided by the decline in operating revenues between the same years. The analysis suggests that federal support to airports offset approximately 63% and 82% of the operating revenue losses experienced by airports in FY 2020 and FY 2021, respectively. This masks how the government support was used by airports (such as debt serving) and may include other non-COVID support (which may explain why support to smaller airports was over 100% of revenue losses). Nevertheless, it does illustrate the scale of support provided by the federal government.

Analysis suggests that federal support to airports offset approximately 63% and 82% of the operating revenue losses experienced by airports in FY 2020 and FY 2021, respectively.

Operating Expenses, Debt, and Capital Planning

In response to diminishing revenues, airports looked to manage other major line items on their financial statement. Starting in FY 2020, airports attempted to realize savings in operating expenses through hiring freezes or slowdowns, reduced reliance on contractual services, and suspension of nonessential travel and expenses for staff. In many cases, airport tenants were allowed to limit their operating hours. For example, most airport parking operators consolidated their operations by closing some of their parking facilities (often the remote lot), reducing their

![Increase in grant receipts as a percentage of operating revenue losses [analysis of CATS Report, January 2023 (FAA, n.d.-b)]](https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/27987/assets/images/img-32-1.jpg)

Figure 14. Increase in grant receipts as a percentage of operating revenue losses [analysis of CATS Report, January 2023 (FAA, n.d.-b)].

busing operations, and temporarily relocating their employees to close-in facilities. Additionally, larger airports reduced their debt service for FY 2021 and FY 2022 through bond refunding and restructuring, made possible in part with the use of CARES Act funds. In some cases, airports issued debt to reimburse cash expenditures for airport-funded capital projects. Finally, many airports reviewed their capital improvement plans. Some projects, like airside rehabilitation, were sped up to take advantage of quieter operations; other projects were deferred or rescoped to limit capital spending.

The response of airports to the pandemic is explored in more detail in the next chapter, using case studies at 11 airports.