Incorporating Shock Events into Aviation Demand Forecasting and Airport Planning (2024)

Chapter: 5 Other Shock Events and Their Impacts on Airports and the Aviation Sector

CHAPTER 5

Other Shock Events and Their Impacts on Airports and the Aviation Sector

This chapter highlights other examples of events causing shocks in the aviation industry. A major part of being able to better plan for and mitigate future shock events is understanding historical shocks and how they impacted the aviation industry and airports. Some shocks may be unique and true one-off events, while others are variants of a common theme. Typical examples of the latter are natural disasters or the entry of a new carrier leading to rapid growth. Although considered unanticipated by the airports experiencing them, shock events have precedence in history.

Infectious Disease Event: SARS (2002–2003)

The COVID-19 pandemic has been the largest infectious disease event to impact the aviation sector, but it was certainly not the first. The 2002–2003 outbreak of SARS marked the first major outbreak of a new infectious virus in the 21st century and was followed by other disease events, including MERS of 2012–onwards, multiple Ebola outbreaks in Africa starting in 2014, and various zoonotic influenza viruses such as H5N1 (Avian Flu) of 2005, H1N1 (Swine Flu) of 2009–2010, and H7N9 (Avian Flu) of 2013 (these outbreaks generally had less impact on aviation than SARS or COVID-19). Several researchers have argued that the likelihood of pandemics has increased over time, driven by increased mobility, growing urbanization and population density, industrialized food production, globalized supply chains, and the expansion of global transportation networks including air travel (Hall, Scott, and Gössling 2021).

The SARS outbreak brought to light the modern reality that aviation can simultaneously be a potential transmission medium and a victim of pandemics.

The 2002–2003 global outbreak of SARS lasted approximately 9 months from November 2002 to July 2003, marked by a precipitous rise and then fall of cases throughout affected regions, primarily in Asia. In total, there were nearly 8,100 cases and nearly 800 deaths from SARS worldwide throughout this period, with 96% of cases occurring in Asia. Air travelers served as vectors for the disease in the early stages of the global outbreak, flying it to several countries where onward transmission would then occur primarily with infected patients’ family members and within hospitals. At the peak of the global SARS outbreak, more than 30 international airports in 20 countries applied measures to detect infected travelers. Protocols that directly impacted airports and airlines included travel alerts and advisories issued by governments and WHO, passenger screening questionnaires, temperature screening of passengers, contact tracing, media and information campaigns in terminals, quarantine measures, and in-flight protocols such as recommendations to wear masks. In the case of SARS, international coordination and the rate of initial emergency response (or rather lack thereof) proved to be critical in determining the timeline and severity of the pandemic as well as the ability for the disease to spread across borders. Once an outbreak occurred, physical containment efforts were effective in mitigating

further spread, although certain measures taken at airports, particularly temperature screenings, were not necessarily effective given the difficulty in identifying infected travelers.

The impact of SARS on the aviation industry was characterized by a dramatic yet transitory event that primarily impacted international air passenger traffic, most notably marked by a V-shaped recovery, which took less than a year (Figure 16). According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), it is estimated that Asia-Pacific airlines lost approximately 8% of their annual international traffic (in terms of revenue passenger kilometers or RPKs), amounting to $6 billion in lost revenue. North American airlines were far less involved directly with the outbreak but still lost 3.7% of their annual international traffic amounting to an estimated $1 billion in lost revenue.

Overall, it took 9 months before global international passenger traffic returned to precrisis levels, though the recovery timeframe varied widely across affected airports. Monthly traffic levels declined by as much as 40% to 80% (relative to 2002 levels) at major Asian airports in Beijing, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore. In Toronto, the largest hotspot for SARS cases outside of Asia, quarterly total air traffic at Toronto Pearson Airport declined by as much as 14% relative to the prior year. Passenger declines lasted anywhere between 6 and 10 months before returning to precrisis (2002) levels. Conversely, in the United States, which was not significantly affected by SARS directly, declines in air traffic were limited to passengers coming from hotspot regions. During the months of the global SARS outbreak (March to July 2003), international traffic to the United States declined by 4% (U.S. DOT, n.d.). LAX and SFO, which had the most passengers from China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan) and Singapore, saw traffic from these Asian hotspots fall by nearly 50% during the global outbreak (relative to 2002 levels). However, passengers from these places accounted for less than 5% of total traffic at those airports, making the overall impact relatively small.

Airports, government authorities, and other stakeholders took several actions in the aftermath of the global SARS outbreak to aid traffic recovery and plan for future health crises. Various forms of financial relief were administered to help shoulder the costs associated with lost air traffic during the outbreak as well as to help stimulate the return of travelers. Beyond immediate

Figure 16. Impact of SARS on Asia-Pacific and North American airlines’ international traffic (Pearce 2006).

recovery efforts, governments and airports contended with the need to improve emergency response protocols for future crises. Some governments restructured or centralized their public health systems to help establish clearer protocols and hierarchies across governing bodies, including transportation authorities. For instance, the SARS outbreak was a pivotal event for Taiwan; the slow initial response to combat and contain SARS incited the government to establish a centralized public health system responsible for crisis management over all major authorities, including those that govern or operate transportation, customs, and immigration. This centralized agency enabled processes to rapidly implement passenger screening, case monitoring, and contact tracing for travelers and the country as a whole. These measures have been credited with helping Taiwan manage subsequent emergencies, particularly COVID-19 (Hall, Scott, and Gössling 2021).

For airport infrastructure, research across the industry emphasizes the benefits of airport planning and facility designs that incorporate open terminal layouts and flexible or movable infrastructure to help quickly implement emergency processes like fever screening, infection control, and physical distancing (HOK Architects 2020). Flexibility, in particular, is key given that not all emergencies are the same; even minor differences between SARS and COVID-19 resulted in far different pandemics, and not all of the physical containment efforts that worked for SARS were effective for COVID-19 (Wilder-Smith, Chiew, and Lee 2020).

The SARS outbreak brought to light the modern reality that aviation can simultaneously be a potential transmission medium and a victim of pandemics. The international connectivity and speed afforded by air travel when compared to the incubation period of many infectious diseases, means that air travel can be a significant factor in turning a local epidemic into a global pandemic under the right conditions. Airports, particularly major international or gateway airports, are often identified (fairly or unfairly) as the key transit points through which diseases may be imported and therefore will directly bear the impact of restrictions on movement and travel.

9/11 Terrorist Attacks

The terrorist attacks of 9/11 were one of the most significant shock events affecting the United States and global aviation industries in the last 30 years. The attack was carried out by the extremist group Al-Qaeda, involving the hijacking of four commercial U.S. airplanes with the intent of crashing them into major U.S. commercial and political institutions. Two of the planes were flown into the twin towers at the World Trade Center complex in New York City, a third plane was flown into the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, and the last plane was destined for Washington, DC but instead crashed into an empty field in Pennsylvania following a revolt against the hijackers by the passengers onboard. Altogether, the attacks claimed the lives of nearly 3,000 people, including passengers onboard the hijacked flights as well as civilians and first responders caught in the targeted areas on the ground.

As the events of the morning of September 11th unfolded, the FAA suspended all civilian flights and shut down U.S. airspace, ordering all flying aircraft to land at the nearest available airport as well as all inbound international flights to divert elsewhere. Due to the shutdown of U.S. airspace, inbound international flights to the U.S. were either returned to their origin airport or redirected to land at airports in Canada or Mexico. All civilian flights in the United States remained grounded for 3 days. Certain airports were shut down for longer: Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport in Washington, DC, was closed for 23 days and opened gradually over a span of 6 months, with restrictions such as bans on large aircraft, GA, nighttime operations, and certain flight paths.

When commercial air travel resumed, airlines and airports had to contend with a drop in demand amid dampened economic conditions and a lower willingness among the public to fly,

along with immediate changes to enhance airport security in the interim. For instance, in the months following 9/11, airport security screening was conducted with the assistance of armed National Guard soldiers and local and state police in some places. Security lines grew as officers introduced additional screening measures like searching carry-on bags and patting down passengers even before more formal regulations were introduced.

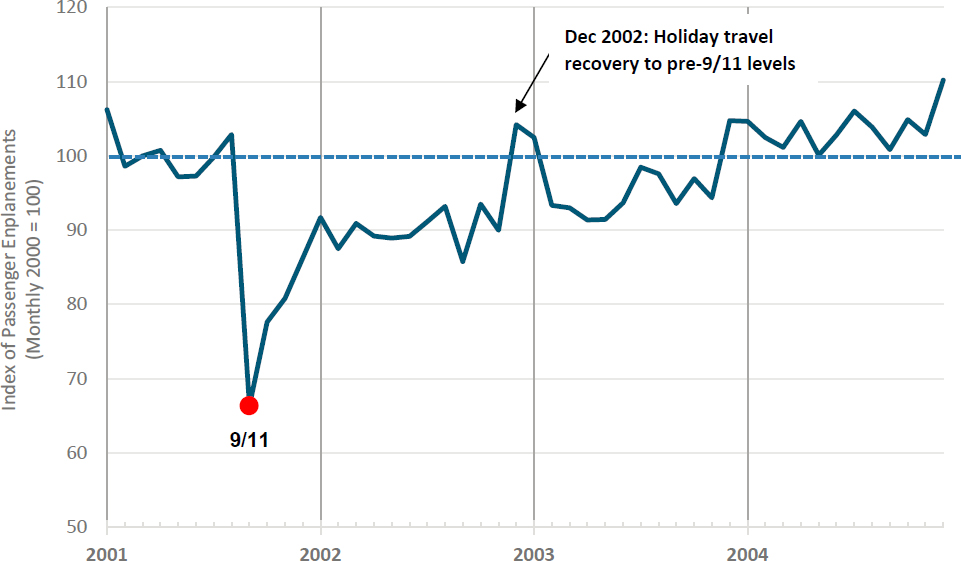

Figure 17 shows monthly passenger traffic at commercial airports within the United States in the year after 9/11. September 2001 traffic dropped by one-third relative to September 2000, with subsequent months in 2001 remaining 15% to 20% below the prior year’s levels. Nationwide, monthly air traffic would not return to pre-9/11 levels until the holidays in late 2002, while nonholiday seasonal traffic took until 2004 to recover and begin growing again. More broadly, 9/11 diminished consumer confidence and slowed economic growth, which had already been dampened by the dot-com bust in preceding years, while fears over the safety of air travel persisted. The downturn in air traffic added pressure on U.S. airlines, driving cost-cutting measures and reductions in capacity and network realignments across the country. To support U.S. airlines for lost revenues associated with the mandatory groundings in September 2001 as well as additional anticipated losses in air traffic as a result of 9/11, the federal government introduced the Air Transportation Safety and System Stabilization Act (2001). This provided $5 billion in compensation and $10 billion in loan guarantees for approved U.S. airlines.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks led to a transformation of aviation security. The Aviation and Transportation Security Act (ATSA) in November 2001 federalized the security screening of passengers at airports and established the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) to manage it. In addition, the ATSA mandated the screening of all checked baggage. Prior to the ATSA, aviation security was privatized and fell under the responsibility of airlines, which often hired screening companies to perform actual duties at airport security checkpoints. By the end of 2002, the TSA began overseeing

The 9/11 terrorist attacks led to transformation of aviation security impacting airport operations and planning.

Figure 17. U.S. passenger traffic index, 2001–2004 (monthly 2000 = 100) (U.S. DOT, n.d.).

security operations and federal screening mandates at all commercial airports in the United States, thus ushering in many of the security screening measures and luggage limitations that are now commonplace for commercial air travelers. By the end of 2002, the newly established TSA had hired approximately 56,000 agents for both passenger and baggage screening at airports, nearly 3.5 times the estimated 16,200 private security screeners that were employed at U.S. airports before 9/11 (Blalock, Kadiyali, and Simon 2007). This headcount was later scaled back to just over 45,000 screeners by 2004.

These new regulations substantially changed airport operations and had a particular space-constraining effect on preboard security facilities that were originally designed for a pre-9/11 operating environment. In particular, the added passenger and baggage screening protocols created the need for expanded inspection areas to accommodate more security agents and other personnel, larger screening equipment, and longer lines and processing times of passengers and baggage. Due to more intensive security screening requirements, the processing rate at passenger screening checkpoints dropped from 500 to 600 passengers per hour per lane before September 2001, to 100 to 150 passengers after 9/11 (de Barros and Tomber 2007). This translated into much longer queues and wait times for passengers and additional space requirements to accommodate longer queues.

Beyond the resource-intensive nature of the screening procedures themselves, ATSA impacted other airport planning considerations, such as the clearer delineation between pre- and post-security terminal areas and the prohibition of nonpassengers from the post-security side. Before 9/11, nontraveling family and friends could accompany passengers to their gates, adding to the number of customers potentially spending money at terminal concessions, which was a source of revenue for airports. The new regulations not only reduced this source of concession demand but also forced airports to reconsider the layout and accessibility of concessions (e.g., food and beverage, retail) between pre- and post-security locations.

The reality remains that much of the airport infrastructure in the United States was not originally designed for a post-9/11 operating environment. According to a 2021 infrastructure assessment by Airports Council International-North America, the average U.S. airport terminal is over 40 years old, which means that many facilities were built before 9/11 and have undergone multiple rounds of structural and operational changes to accommodate the changing security landscape (ACI-NA 2021).

Extreme Weather Event: Hurricane Katrina

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina came ashore about 60 miles southeast of New Orleans, with wind speeds of up to 127 miles per hour and a storm-driven wave surge of up to 30 feet. The size and strength of the storm and subsequent flooding resulted in one of the largest natural disasters in U.S. history. Storm waters flowed over floodwalls and breached levees in Louisiana’s Orleans and neighboring parishes, causing widespread flooding, billions of dollars of property damage, and, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), more than 1,300 deaths in the United States. Although the airfield of Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport (MSY) did not experience flooding during Hurricane Katrina, the airport’s facilities suffered extensive wind and water damage (the airport is just 3.7 ft above sea level and has a perimeter dike to limit damage from storm surge). During the immediate period of the storm and recovery, MSY was closed to commercial air traffic but supported humanitarian and rescue operations.

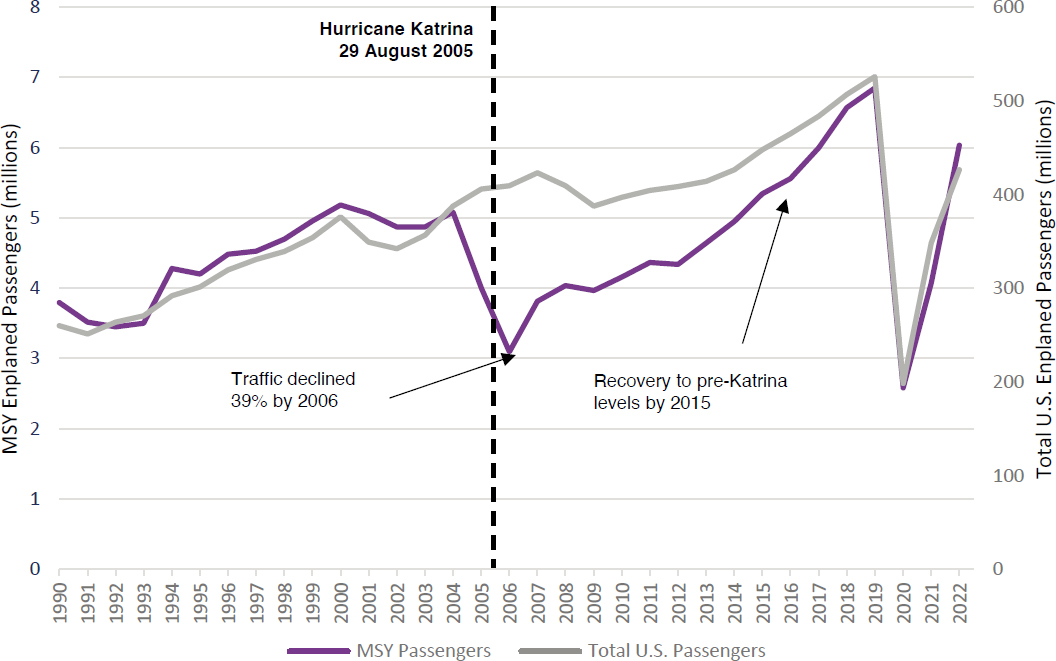

Figure 18 shows enplaned passenger traffic at MSY in the years before and after Hurricane Katrina. The hurricane led to a 39% decline in enplanements between 2004 and 2006 (from

5.1 million passengers to 3.1 million). Before the hurricane, traffic development at the airport was broadly following the U.S. average (the trend in total U.S. traffic), but after Katrina, traffic at the airport greatly diverged from this trend, with the result that passenger enplanements did not return to prehurricane levels for 10 years. In more recent years, traffic growth was one of the highest among U.S. airports, due to the entry and build up of services by ULCCs (Spirit and Frontier Airlines) along with growth by established carriers. With the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, traffic at the airport declined by 62% that year, in line with the national average.

The protracted recovery after Hurricane Katrina was due in large part to two key factors outside the control of the airport—population decline and tourism recovery. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that the population of the City of New Orleans, which was already slowly declining before Hurricane Katrina, dropped by 54% in 2006 due to the loss of housing and economic activity caused by the hurricane, which prevented those who had been evacuated from returning to the city. About half of the initially lost population was recovered by 2010, and by 2019, the city’s population was 14% less than the 2005 level. Similarly, the population of the wider metropolitan statistical area was 9% lower in 2010 (than in 2005) and 3% lower in 2020. Tourism, in addition to convention tourism, is a major sector in New Orleans, attracting both domestic and international leisure travelers. The City is also a home port for cruise ships where passengers start or end their cruise holiday, thus generating traffic for MSY in the form of passengers. The University of New Orleans Hospitality Research Center reported that visitors to New Orleans declined by 63% between 2004 and 2006 (from 10.1 million to 3.7 million) and did not recover to pre-Katrina levels until 2016.

Following the hurricane, the airport put airline incentives in place to stimulate the return of air services, offering reduced charges for carriers reintroducing capacity or adding new routes. More recently and before the pandemic, the airport had attracted additional international air

service to the UK and Germany. In May 2021, Breeze Airways (a domestic LCC formerly known as Moxy Airways, founded in 2018), announced the development of an operating base at MSY (Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport 2021).

In 2013, the airport undertook a Long-Term Strategic Development Plan that included construction of a new North Terminal (opened in 2019). The terminal was built with storm resilience in mind, with the use of extensive wind-tunnel modeling and on-site testing to ensure that the terminal could withstand hurricane-force winds. On August 29, 2021, New Orleans was hit by Hurricane Ida, a Category 4 hurricane, which was more powerful but more compact than Hurricane Katrina when it made landfall. The hurricane did not bring about the same scale of devastation to New Orleans as Hurricane Katrina, owing to the levees that had been upgraded after Katrina and did not fail this time. The airport remained technically open throughout the hurricane although all flights were cancelled for several days. The airport reported that no significant damage was caused to the new terminal.

Great Recession of 2008–2009

Economic recessions are not surprise events in the sense that they happen relatively frequently and with considerable historical precedent. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), there were 10 U.S. recessions between the end of the Second World War up to 2007, roughly once every six years. Nevertheless, the timing and extent of the recession, and their implications for aviation, are impossible to accurately predict.

The Great Recession (also known as the Great Financial Crisis) of 2008–2009 was the largest recession experienced in the United States since the Great Depression (1929–1933). NBER records that the United States was in recession for 1.5 years (December 2007 through June 2009) and experienced a 5.1% decline in gross domestic product (GDP) (peak to trough). Previous recessions since the Second World War generally lasted 6 to 12 months and caused GDP declines of 0.3% to 3.7%. The economic recovery was also slow in comparison with past recessions—GDP did not recover to prerecession levels until 2013, and even then, it was considerably below the prerecession trend.

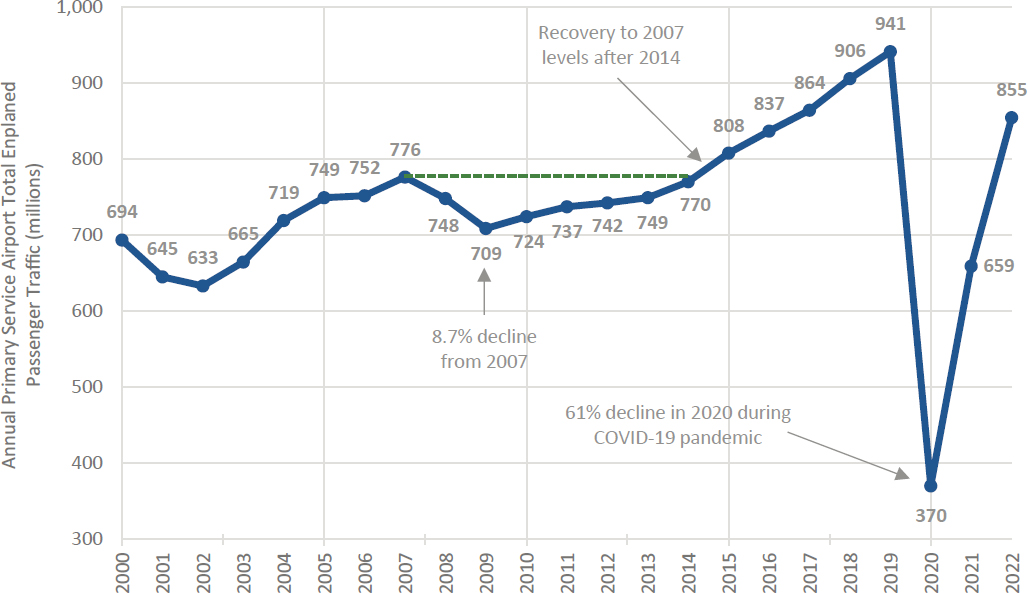

Figure 19 shows that, at a national level, passenger enplanements declined 8.7% between 2007 and 2009. Passenger traffic did not recover to prerecession levels until after 2014, 5 years after the decline and 7 years after the start of the recession. In comparison, traffic took 2 years to recover after 9/11 (the traffic decline following 9/11 was also 8.7%). Having recovered to prerecession levels, there was robust growth in passenger traffic averaging 4.1% per annum, between 2014 and 2019.

The recovery from the Great Recession differed considerably by airport size. Large hub airports (30 airports, which accounted for approximately 71% of passenger traffic in 2019) experienced the smallest declines on average and had the fastest recovery (by 2012). On average, medium and small hubs (17% and 9% of total traffic in 2019, respectively) had steeper declines in traffic and a recovery that was 3 to 4 years longer than for large hubs. In contrast, nonhub airports (4% of passenger traffic) generally experienced a smaller decline and a faster recovery.

The impact of the Great Recession differed by airport size with medium and small hub airports experiencing the largest declines and slowest recovery.

The uneven nature of the recovery is further illustrated by analyzing the proportion of airports that had lower traffic levels in 2014 and 2019 than they did in 2007, shown in Table 3. Approximately 55% of airports had not fully recovered traffic lost during the Great Recession by 2014, and 32% had not recovered traffic by 2019. Only two out of 30 (7%) large hub airports had not fully recovered traffic by 2019 (IAD and HNL), whereas approximately a third of

medium, small, and nonhubs had not recovered to 2007 traffic levels (13 medium hub airports, 29 small hub airports, and 138 nonhub airports). By 2014, 20% of these airports were down by 25% or more of their 2007 traffic levels, and 13% were still in this position in 2019.

There are multiple reasons for the lack of recovery at one-third of airports, many specific to the individual airports. However, significant factors were airline service reductions, dehubbing, and station closures (particularly at medium hubs) that took place in response to the recession, although airline consolidation played a role in some cases. In 2008, seven major airlines accounted for 80% of seat capacity in the United States: Southwest Airlines, American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, US Airways, United Airlines, Continental Airlines, and Northwest Airlines. With a number of mergers between 2008 and 2013, these seven carriers were reduced to four: Southwest Airlines, American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, and United Airlines. While the Great Recession was not the sole reason for these mergers, the financial difficulties that some airlines experienced over this period likely contributed to the rationale for the mergers. As a result of the Great Recession and airline mergers, several airports experienced a significant loss of capacity or airline dehubbing.

Table 3. Percentage of airports by hub type with lower traffic levels in 2014 and 2019 than in 2007.

| Airport Type | Airports with Lower Traffic in 2014 than in 2007 | Airports with Lower Traffic in 2019 than in 2007 |

|---|---|---|

| All Airports | 55% | 32% |

| Large Hubs | 43% | 7% |

| Medium Hubs | 81% | 35% |

| Small Hubs | 61% | 31% |

| Nonhub | 51% | 35% |

SOURCE: U.S. DOT, n.d.

The period after the Great Recession also saw the development of ULCCs such as Spirit Airlines, Allegiant Air, Sun Country Airlines, and Frontier Airlines. ULCCs are characterized by very low base fares with ancillary charges for additional services and lower unit costs than traditional LCCs achieved through reduced labor costs and higher aircraft utilization. According to U.S. DOT Form 41 T100 Segment data (U.S. DOT, n.d.), ULCCs accounted for 30% of seat growth between the trough of the traffic decline in 2009 and 2019. Furthermore, ULCCs have tended to deploy more of their capacity at smaller airports. Between 2009 and 2019, 41% of ULCC capacity was deployed at medium hubs, small hubs, and nonhubs, compared with 19% for all other carriers. ULCCs added four times as much seat capacity at nonhub airports as all other types of carriers. The impact of carrier exit and entry on individual airports is examined in the next sections.

Loss of a Carrier or Dehubbing

The loss of a major carrier (or carrier dehubbing) can lead to a substantial loss of air service and with it, passenger (or cargo) volume. It can also lead to a fundamental change in the long-term course of traffic development. This section examines three examples of carrier loss or dehubbing:

- St. Louis Lambert International Airport, Missouri (STL) – loss of TWA hub (Exhibit 1).

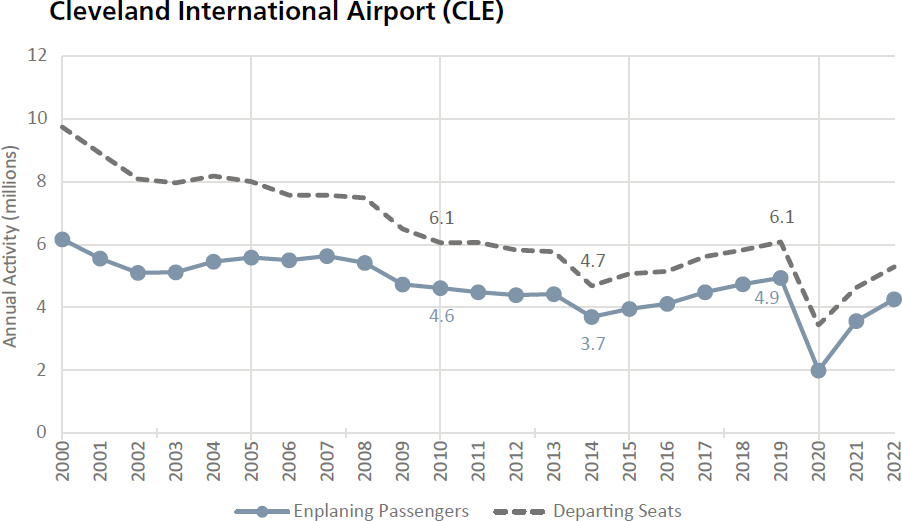

- Cleveland International Airport, Ohio (CLE) – United Airlines dehubbing (Exhibit 2).

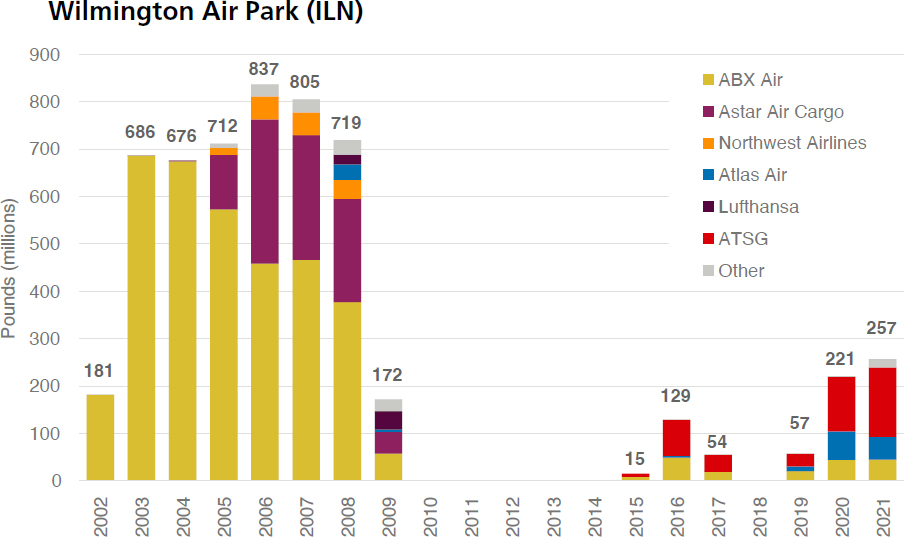

- Wilmington Air Park, Ohio (ILN) – loss of cargo carrier services (Exhibit 3).

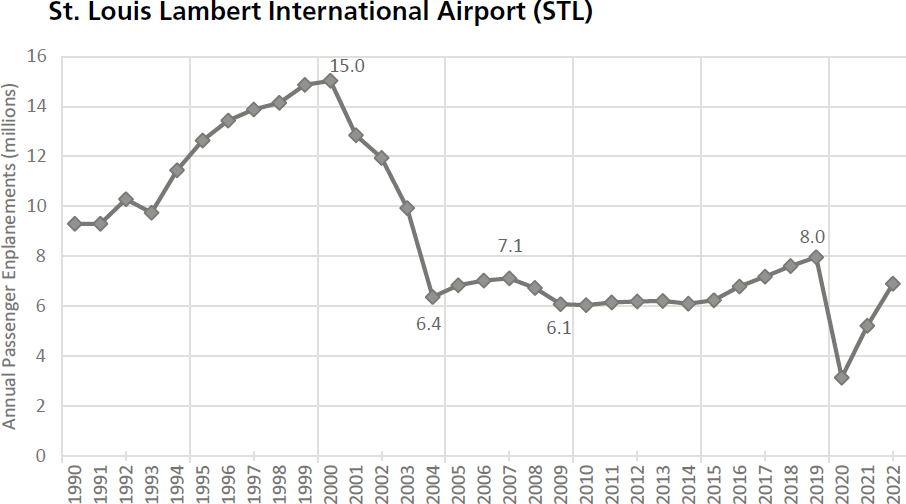

In 1982, TWA named STL as its principal domestic hub resulting in rapid passenger growth at the airport during the 1980s. Despite entering bankruptcy in 1992 and 1995, TWA continued to grow traffic at STL, with the airport reaching 15 million enplaned passengers in 2000 (TWA accounted for 71% of passengers in that year). However, in 2001 TWA declared bankruptcy for the third time, which resulted in American Airlines acquiring TWA’s assets. American Airlines initially indicated that it planned to keep STL as a hub, partially due to congestion at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport (ORD). However,

with the severe downturn in traffic that followed 9/11, American Airlines closed its STL operations, focusing more on its main hub operations at ORD and DFW. As a result of cutbacks by American, passenger volumes declined to 6.4 million passengers by 2004 representing a 57% decrease in airport traffic since its peak in 2000. There was a modest recovery in traffic to 7.1 million in 2007 before the Great Recession led to further declines.

The loss of traffic following the TWA/AA dehubbing was largely through connecting passengers, as O/D traffic was far less affected. O/D traffic was 5.7 million enplanements in 2000, which declined by 12.1% in 2004 but recovered to 5.9 million in 2019 (slightly higher than in 2000). Much of this traffic growth since 2010 was driven by LCCs such as Southwest Airlines and Frontier Airlines. However, STL’s traffic has fundamentally changed since the dehubbing with the majority of current traffic comprising originating passengers, whereas during TWA hub operations pre-2001, more than half of all enplanements were attributed to connecting passengers.

CLE had been a hub for Continental Airlines since the 1990s, with the airline accounting for 70% of passengers by 2010. When Continental merged with United Airlines in 2010, the merger agreement (with the Ohio Attorney General) required the airline to maintain 90% of its premerger capacity for 2 years. In 2014, the merged United Airlines announced the termination of CLE as a hub and a 60% service reduction (relative to 2010), citing long-term losses at the airport. Despite United’s dehubbing of CLE in 2014, seat capacity actually increased every year until the COVID-19 pandemic. LCCs and ULCCs, such as Southwest Airlines, JetBlue Airways, Frontier Airlines, and Spirit Airlines, grew capacity at CLE as did Delta Air Lines and American Airlines. While O/D passengers grew at an average of 7.9% per annum between 2013 and 2019, or in aggregate 57%, connecting passengers declined by 89% over the same period.

After dehubbing CLE, the airport’s Concourse D was closed, and United consolidated its operations into Concourse C. However, the carrier was still required to pay the airport $1.1 million per month in rent for the facility until 2027. Concourse D remained vacant

as of 2022. The airport completed a master plan update in 2021, which recognized the need for the facility to focus on O/D traffic rather than connecting flows as it had done during the era of Continental and United’s hub operations. For example, the potential for increased demands on parking facilities, roadways, and ticketing areas as a higher proportion of future traffic demand is expected to be from originating passengers, rather than connecting.

Previously an air force base, ILN, located in Southwest Ohio, was purchased by cargo airline Airborne Express in 1980, making it the first airline to purchase its own airport in the United States. In 2003, Airborne Express was acquired by German logistics and courier company DHL. DHL took ownership of the airport’s ground operations, while the air business was spun off as a separate company called ABX Air, which operated services under contract to DHL. As a result, cargo volumes, aircraft activity, and employment at the airport expanded rapidly. In November 2008, DHL announced that it would shut down its express delivery service within the United States, including its ILN operations, due to severe financial losses in the U.S. domestic market. The withdrawal of DHL resulted in the loss of almost 8,000 jobs in Wilmington and the cessation of almost all cargo operations by carriers contracted to DHL such as ABX Air, Atlas Air, and Astar Air Cargo. DHL agreed to transfer ownership of the airport and facilities to Clinton County.

Air cargo at the airport was largely dormant until 2015 when a number of carriers (ATSG, ABX, and others) began operating flights for Amazon’s e-commerce deliveries using Boeing 767s, which was later formalized under the Amazon Air brand. In early 2017, Amazon decided to move flight operations from ILN to Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport (CVG) where it was building its main hub, resulting in the loss of all operations in 2018. However, in 2019, Amazon Air returned to ILN to meet growing e-commerce demand as its new CVG hub facility was under construction, with a rapid expansion in services driven by the growth of e-commerce activity during the pandemic.

Conclusion

In all three cases, the shock event was caused by the business decisions of the airport’s largest customer. In 2019, 57% of commercial airports had over half their passenger seat capacity operated by a single carrier (including regional subsidiaries), including 43% of large hub airports. This creates a risk that the airport will be subject to the actions of that carrier creating a shock event not anticipated in air traffic forecasts. In the case of STL and CLE, airline dehubbing led to a decline predominately in connecting traffic, while O/D traffic was less affected. This does not mean that the local community is not impacted—connecting traffic allows carriers to support a higher level of service (frequencies and routes) than can be achieved from O/D traffic alone. All three airports sought to diversify their carrier mix and revenues, leading to a partial recovery in traffic, but undoubtably behind the trend anticipated before the shock event.

Carrier Entry or Rapid Traffic Growth

Rapid carrier development at an airport, especially smaller airports, can also be a shock event that while being positive for business development can present challenges in facility management and design. This section examines the impacts of rapid traffic development at three airports:

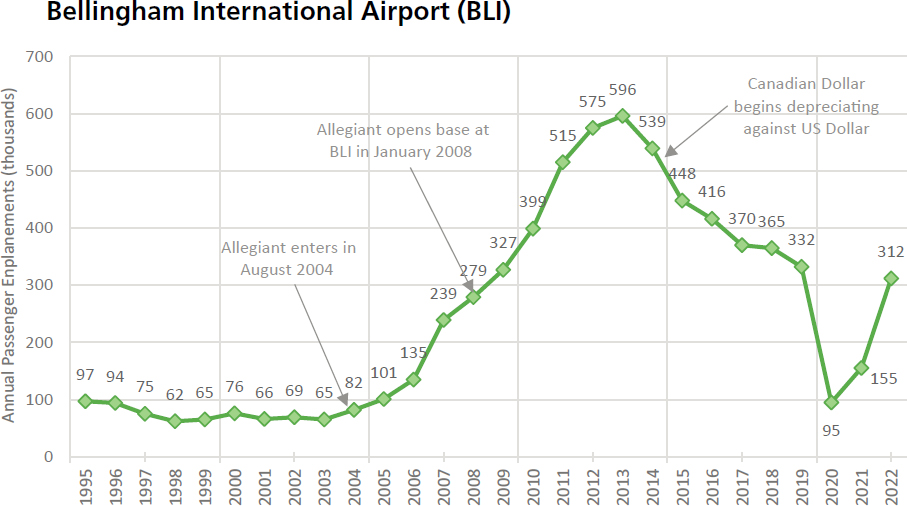

- Bellingham International Airport, Washington (BLI)—Allegiant and Southwest Airlines (Exhibit 4).

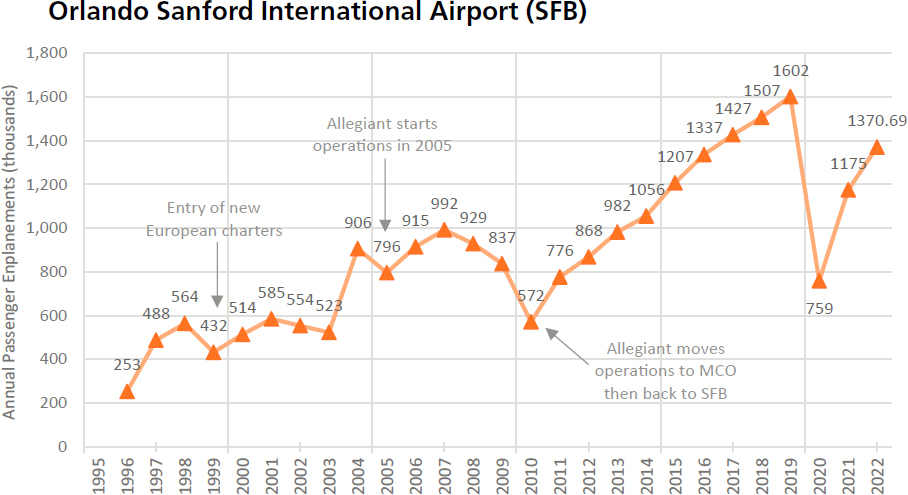

- Orlando Sanford International Airport, Florida (SFB)—Allegiant Airlines (Exhibit 5).

- Williston Basin International Airport, North Dakota (XWA) (Exhibit 6).

Before 2004, passenger enplanements at BLI averaged around 75,000 per annum, with the majority of capacity being operated by Horizon Air (the regional subsidiary of Alaska Airlines) with service to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. In August 2004, ULCC Allegiant Air entered the market at BLI, with service to Las Vegas. As Allegiant grew its operations at BLI it opened its sixth base at the airport in 2008. Passenger enplanements grew from 64,975 in 2003 to 596,383 in 2013, a ninefold increase and an average growth rate of 24.8% per

annum, with service to 10 destinations. A large proportion of BLI passengers originated from Canada, as the airport was located 21 miles south of the border with Canada and offered considerable fare and tax savings relative to Canadian airports (Vancouver and Abbotsford in particular), especially with a historically strong Canadian dollar over this period (versus the U.S. dollar). As the Canadian dollar started to weaken in 2014, passenger volumes at BLI started to decline. Allegiant reduced capacity in response, and by 2019 passenger volumes at BLI had declined 44% relative to the peak in 2013.

To address rapid traffic growth when Allegiant Air entered the market, BLI accelerated its expansion program, completing a $29 million resurfacing project for the runway, followed by a terminal expansion project completed in 2014, which tripled the size of the old terminal building. The airport sought to remain competitive and attractive to both new and existing carriers by maintaining low-cost levels and offering incentive programs to carriers. In November 2021, Southwest Airlines began daily direct service from BLI to Oakland, California, and Las Vegas, and by the end of 2022 was offering service to eight destinations.

Previously a military and then GA facility, SFB started to receive commercial air service in the mid-1990s following the building of a new passenger terminal. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, commercial operations largely comprised charter services from Europe (particularly the UK). Allegiant Airlines started operations in 2005 and rapidly grew operations (offsetting the loss of some international charter services) and by 2009 accounted for 70% of passengers at the airport. In 2010, Allegiant announced it was moving all of its operations to Orlando International Airport (MCO) in part to compete with AirTran Airways at the larger airport. However, the airline moved all operations back to SFB by February 2011 due to customer feedback. Since returning in 2011, the airline almost tripled its seat capacity at SFB by 2019, operating over 70 routes and accounting for 93% of seat capacity at the airport. Allegiant has been almost the sole driver of growth, with capacity by other (largely international) carriers declining by 61% between 2011 and 2019 due to carriers failing or moving to MCO. Passenger volumes declined 53% in 2020 due to the pandemic, less than the national average of 61%.

Allegiant further expanded its presence at the airport in 2016 by building its East Coast Training Center at Sanford. The Center can train 150 pilots, 500 flight attendants, and 100 mechanics annually on a full range of flight simulators, cabin trainers, and classroom resources for A320 and MD80 aircraft. Sanford Airport Authority has sought to diversify its carrier mix and in late 2021 attracted two Canadian LCCs, Swoop Airlines and Flair Airlines, to begin service between Sanford and Canadian cities in late 2021. Given the depth of the Orlando area destination market, the airport has sought to respond to opportunities as more international cities became available prospects for air service development.

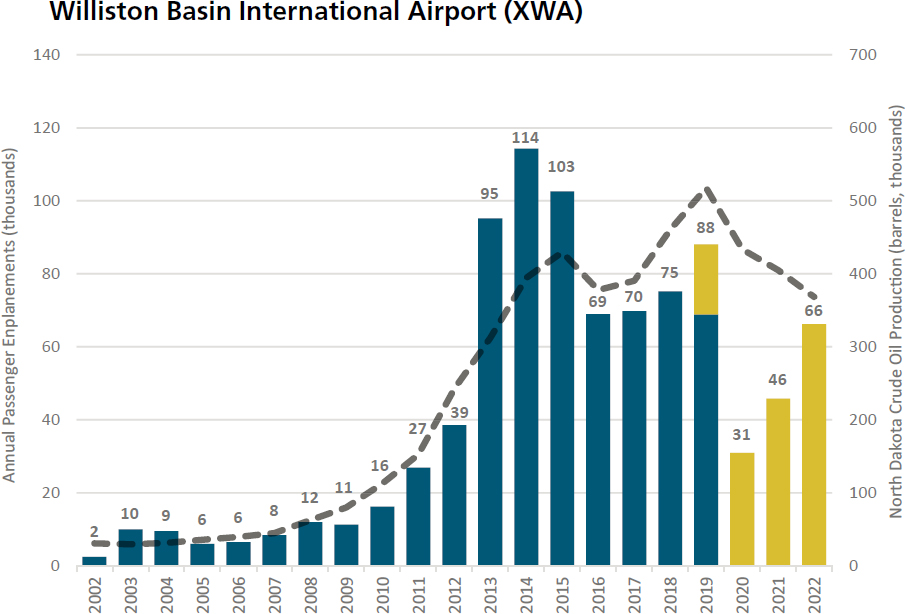

XWA is a new airport that opened in October 2019 to replace Sloulin Field International Airport (ISN) as the latter was unable to handle the increased traffic in the region.

Williston, North Dakota, became a center for the shale oil industry following the discovery of the Parshall Oil Field in 2006, part of the Bakken Formation. As oil industry activity increased between 2006 and 2014, passenger traffic at ISN increased rapidly, peaking at 114,325 in 2014, a tenfold increase over 7 years. The initial growth was supported by regional carrier Great Lakes Airlines, operating six routes using 30-seat Embraer EMB 120s. In 2012, United Airlines entered with service to Denver and later Houston (operated by a regional subsidiary). Delta Air Lines also started service in 2012 to Minneapolis—St. Paul, operated by a regional partner. Due to the significant increase in demand, ISN was not able to cope with the additional activity and capacity, and plans were implemented to construct a new airport to meet the demand of the growing region and energy industry.

XWA construction started in 2016 as a replacement for ISN due to the latter’s capacity and operational constraints (building a new airport was determined to be cheaper than

upgrading ISN). Traffic volumes at the airport declined from 2014 due to reduced oil industry activity (the chart above shows a strong correlation between oil production and air traffic). Great Lakes Airlines pulled out from the airport in 2014 citing a pilot shortage and both United Airlines and Delta Air Lines reduced frequencies at the airport, with United cancelling the Houston service in 2016. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a 65% decline in passenger traffic in 2020, with United and Delta operating reduced service levels in line with passenger traffic but have continued services into 2021. ULCC Sun Country Airlines started twice weekly service to Las Vegas in September 2021.

Conclusion

All three airports faced the challenge of growing facilities as a consequence of rapidly growing demand while also being cognizant of the risk from competing airports, economic conditions, and carrier decisions that could result in fluctuating traffic volumes. Small airports are particularly challenged by this form of shock event as introductions of new carriers or substantial increases in service can move airport activity levels well above previously forecasted long-term trend levels. While traffic growth is generally welcomed, these airports do not necessarily have the facilities to accommodate rising traffic volumes, leading to the need for considerable capital development.