Incorporating Shock Events into Aviation Demand Forecasting and Airport Planning (2024)

Chapter: 8 Addressing and Mitigating Shock Events

CHAPTER 8

Addressing and Mitigating Shock Events

The issue of how organizations can better prepare themselves for and respond to uncertainty (including shock events) is covered in a broad range of literature on strategic planning under uncertainty (Courtney, Kirkland, and Viguerie 1997; Amram and Kulatilaka 1999; Thoren and Vendel 2019). The basic premise is that many organizations cannot reliably predict the future and so need to deploy methods for addressing uncertainty, such as scenario planning that considers radical alternative futures and helps develop a portfolio of actions that provide flexibility to changing outcomes. Linden (2021) argues that the COVID-19 pandemic and past shock events demonstrate that aviation is subject to considerable uncertainty and that approaches deployed for strategic planning under uncertainty could benefit the industry. This is illustrated in Figure 27, where traditionally, airport planning has generally followed the classical strategic management approach illustrated on the left, whereas, in fact, airports may face a more ambiguous and unpredictable future as shown on the right.

Many organizations cannot reliably predict the future and so need to deploy methods for addressing uncertainty, such as scenario planning that considers radical alternative futures and helps develop a portfolio of actions that provide flexibility to changing outcomes.

The following sections discuss methods for addressing and managing uncertainty and shock events in the general literature and within the aviation sector.

Methods for Supporting Strategic Planning Under Uncertainty

The literature surveyed generally offers the approach that risk identification is one of the primary ways to mitigate shock or surprise events. A number of papers advocate for implementing risk identification and management strategies to guard against future shock events. This “early warning” and exploration of potential threats are seen particularly in project management literature such as Hajikazemi et al. (2016), Ramasesh and Browning (2014), and Kim (2012). These authors suggest that if there can be greater attention paid during risk management analysis to imagining potential threats and their consequences, then organizations can be better prepared to avoid surprise shock events that have not been imagined. This sentiment appears to be broadly shared across industries and literature, and this approach of explicating the identification of risk factors (including shock events) and developing response strategies is the primary method put forward to deal with shock events.

Another mitigation strategy discusses the value of organizations being flexible in operations and planning in order to adapt to shock events or uncertain outcomes. Duarte Pardo (2016) discusses the benefits of flexibility in the setting of an infrastructure public-private partnership contract as well as infrastructure design that can accommodate a range of potential future outcomes.

The author points to forecasting methods that can provide quantification of risk and a range of scenarios, including consideration of potential shock events, as one strategy along with real-options analysis to value risk as part of contract development.

More broadly, this is captured in the concept of “real options” (Trigeorgis 1996). Like financial options, a real option is the right, but not the obligation, to take a certain course of action. Real options apply this approach in the real, “physical” world rather than the financial world (although real options still have financial implications). The concept started to develop in the 1970s and 1980s as a means to improve the valuation of capital investment programs and offered greater managerial flexibility to organizations. Real options and real-options analysis are used in many industries, particularly those undertaking large capital investments (e.g., oil extraction and pharmaceutical). The greater flexibility that real options provide can have significant value to the decision-maker but can often (but not always) impose a cost. The trade-off between the value of a real option and its costs will need to be evaluated by the decision-maker.

Scenario Planning

In examining the literature on strategic planning under uncertainty, the use of scenario planning (or variants thereof) was frequently discussed. Scenario planning is generally credited to Herman Kahn of the RAND Corporation who developed the methodology to aid the U.S. military, with much of the research related to shock events in support of the military and more recent antiterrorism (Chermack 2011). This approach is related to the scenario forecasts previously described but involves a more-developed approach to incorporating these scenarios into organizational management and decision-making.

An often-cited example of the successful use of scenario planning is at the Shell oil company (Wack 1985; Wilkinson and Kupers 2013). In the 1960s, Shell (then called Royal Dutch Shell) invested in emerging computer technology to forecast its business outlook. However, the forecast model could only forecast out 6 years due to computational limitations, which was too short when considering investment in oil projects, and the results were frequently wrong. Instead, Shell moved to focus on another initiative that started around the same time exploring the use of scenario planning, drawing on the work by Kahn and others. A small team within the company was tasked with developing future scenarios of the oil market and working with management to determine what actions and strategies could be taken to best manage the scenarios. This process was not

The use of scenario planning helped break the habit, common to most corporate planning, of assuming that the future will look much like the present.

about making better predictions of the future but rather about informing organizational processes, such as strategy making, innovation, risk management, public affairs, and leadership development. As noted by Wilkinson and Kupers (2013), the use of scenario planning helped break the habit, common to most corporate planning, of assuming that the future will look much like the present. As unthreatening stories, scenarios enabled Shell executives to open their minds to previously inconceivable or imperceptible developments. The early work included a scenario looking at the oil market switching from a buyers’ to a sellers’ market, resulting in oil price increases of the sort that eventually did occur in the 1970s (the 1973 oil crisis and 1979 energy crisis), albeit for slightly different reasons. This is credited with making Shell management more prepared for the eventuality, if not the timing or the cause, of this oil price shock.

There is no exact structure to the scenario planning process, and a number of variants and formats have been developed. However, the process can be generalized in the following five steps.

-

Identify key drivers or risk factors.

The identification process can vary depending on the nature of the study, but the literature refers to the Delphi method, SWOT (strength, weakness, opportunity, threat) analysis, STEEP (society, technology, environment, economy, and politics), and PESTLE (political, economic, socio/cultural, technology, legal, environment). STEEP and PESTLE are methods for structuring the identification of factors affecting an organization by considering each of the categories encapsulated in the name.

-

Shortlist critical uncertainties.

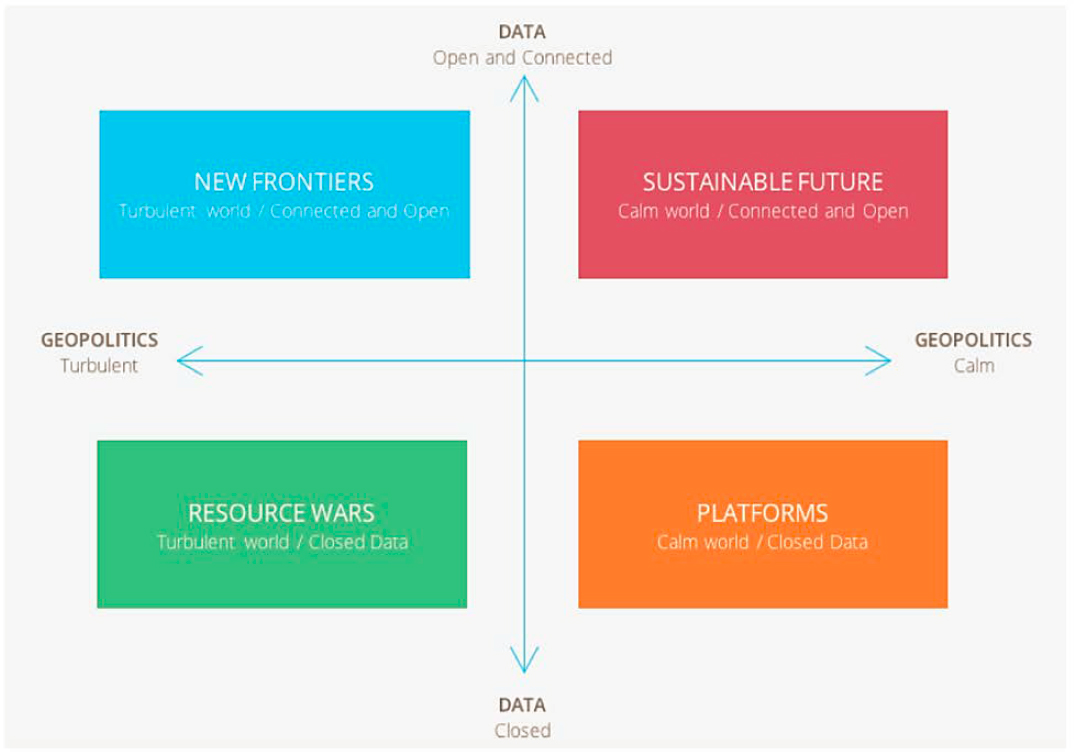

Having established a possibly large set of key drivers or risk factors, the next stage of the process focuses on determining where there is the area of greatest uncertainty, which will give focus to the later scenarios. One common approach is to narrow the focus to two critical uncertainties, which are represented in a 2 by 2 matrix. For example, in 2018, IATA with the School of International Futures (SOIF), conducted a study, Future of the Airline Industry 2035, using STEEP analysis to identify up to 50 drivers of change (IATA and SOIF, 2018). From this, the study team amalgamated and shortlisted critical uncertainties—geopolitics (from calm to turbulent) and data (from open to closed)—into the 2 by 2 matrix shown in Figure 28. This exercise can lead naturally to the development of scenarios based on the four quadrants of the matrix. It should be noted that while this narrowing to two critical uncertainties is common, it is not the only approach. For example, this approach was not used by Shell (Wilkinson and Kupers 2013).

-

Develop a set of plausible scenarios.

The next step is to generate a small number of scenarios based on the information from the previous tasks. The number of scenarios should be small to prevent the exercise from becoming overly complex and unstructured. A maximum of four scenarios is typically recommended (based on the 2 × 2 matrix), but the Shell team initially developed three during their exercises: one status quo scenario plus two divergent alternative scenarios (Chermack 2011). In the 1980s, the Shell team switched to two scenarios as a way of stopping managers from focusing on the “middle way” (Wack 1995). The literature urges avoiding the trap of developing best-case, worst-case, and most likely scenarios or scenarios that reflect purely good or bad outcomes. The scenarios should be plausible but not necessarily probable and relevant to the decision-maker while challenging conventional (or business-as-usual) thinking. They should be more than an “obvious” variation in the business conditions—for example, not simply a ± 20% variation in traffic or oil prices.

There is an emphasis on developing a compelling and realistic narrative with each scenario in order to engage the decision-maker. Chermack (2011) discusses the need for “storytelling” to describe how the scenario develops and how key elements of the scenario work together (although the 2 × 2 matrix focuses on two critical uncertainties, other elements identified

Figure 28. A 2 by 2 matrix of critical uncertainties (IATA and SOIF 2018).

- previously can also be included in the scenarios). While avoiding being overly technical and complex, the scenario needs to provide sufficient detail and richness so that it can generate a meaningful discussion on actions that can be taken. This can include more quantitatively output such as scenario forecasts.

-

Identify actions and strategies that can be deployed.

The process by which the scenarios are used to stimulate dialogue around actions and strategy can vary depending on the nature of the exercise. Scenario planning aimed at overall corporate strategy might be conducted differently from one focused on a specific project or region. Nevertheless, it is generally the case that the scenarios are used as the basis for more interactive discussion (for example, during workshops) to challenge current assumptions and practices and often to develop options for the organization to navigate these scenarios (exploiting opportunities or avoiding/mitigating adversity).

-

Test these actions and strategies against the scenarios and refine them if necessary.

Sometimes this step is combined with step 4 and may involve several iterations between Steps 4 and 5. The aim is to test and challenge either the current strategic approach or the actions developed in step 4. A number of methods have been developed for this purpose:

- Wind Tunneling (Chermack 2011). In design and engineering, wind tunnels are used to test the aerodynamic performance of an object (e.g., a wing, airplane, car, or building). In the context of scenario planning, the scenario is the wind tunnel, and it is the strategic approach or actions that are being tested. The aim is to test decisions for robustness and expose opportunities, risks, and possible improvements to the strategic approach. This is generally conducted through a series of workshops or other interactive methods.

-

- Scenario Immersion (Ralston and Wilson 2006). Scenario immersion is an approach that is similar to wind tunneling and involves structured brainstorming about the implications of a set of scenarios for the organization. In scenario immersion, the scenarios are presented to as many organizational members as possible in a workshop format. Each member of the workshop group is asked to act as a decision-maker and identify strategic responses to those threats and opportunities.

As indicated previously, the aim of scenario planning is not to produce more accurate forecasts of the future, although this can happen indirectly, as with the example of Shell anticipating oil price shocks (the fact that the process can include a variety of viewpoints allows it to benefit from the “wisdom of crowds”). Rather, it is presented as a learning process that challenges conventional thinking and focuses attention on how the future could be very different from the past and the implications of that possibility. The output is a change in mindset and the enhancement of resilience and robustness. It is not a one-off exercise but rather an ongoing process of discovery and adaptation. As stated by Derbyshire (2022, 7), “plausibility-based scenario planning has a role to play in ensuring that what is ‘out of sight’ is not also ‘out of mind.’”

The aim with scenario planning is not to produce more accurate forecasts of the future . . . rather it is presented as a learning process that challenges conventional thinking and focuses attention on how the future could be very different to the past.

War Gaming

A somewhat related methodology to scenario planning referenced in the strategic management literature is business war gaming. As the name suggests, this approach draws from military table-top war simulation exercises. In a military context, these are used to examine war-fighting concepts, train and educate commanders and analysts, explore scenarios, and assess how force planning and posture choices affect campaign outcomes (Oriesek and Schwarz 2008).

In a business context, war gaming is used to develop and test strategies in a competitive business environment. A business war game is usually set up as a role-playing simulation of a dynamic business situation. It involves competing teams, one representing the organization of interest and others cast in the role of certain stakeholders (e.g., a competitor, regulator, consumer). The aim is to play out the possible actions and counteractions in a given scenario (a new corporate strategy, launch of a new product, etc.). The focus is the dynamics between the players of interest under a specified set of conditions. As such, there is less focus on uncertainty and less of a wider perspective than in scenario planning. Some have suggested combining scenario planning and war gaming (Schwarz, Ram, and Rohrbeck 2019), but this approach appears not yet to have been fully developed.

Red Teaming

Red teaming is an approach developed in the military in which a group is formed to try and assess vulnerabilities and limitations of systems or structures. It is used to reveal weaknesses in military readiness to remedy or mitigate those weaknesses. This approach is also used in cyber-security where “white hat” hackers attempt to infiltrate the security of information technology (IT) systems. In some cases, the exercise may also involve a blue team charged with defending the system. The FAA used red teaming to test airport and airline security in the years before 9/11, and the TSA has a Red Team with the mission statement, “Measure TSA screening effectiveness against real-world, intelligence-driven threats in order to inform enterprise risk management and performance improvement” (TSA 2024).

Red teaming has also been used in business planning to test and challenge strategy. As stated by Ryan (2020):

When developing a business strategy, companies often base plans on a best-case scenario, assuming that everything will go to plan. Red teaming exercises help expose strategic gaps or flaws, helping companies scan the business environment for both threats and opportunities.

Red teaming emphasizes contrarian thinking and devil’s advocacy, similar to the elicitation methods described in the earlier section on scenario planning.

Need for Organizational Engagement

A common theme in the literature on strategic planning under uncertainty is the need for full organizational engagement.

A common theme in the literature on strategic planning under uncertainty is the need for full organizational engagement. It is not sufficient to simply identify risks or possible black swans as an exercise; this information needs to lead to meaningful organization changes and the organization’s willingness to be responsive and proactive to these risks. The literature lists examples where risks or shock events were anticipated and even modeled but without leading to any real benefit.

- Lempert, Popper, and Bankes (2002) give the example of General Ridgeway, who, as a young officer, wrote a “war game” about a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor that fellow officers refused to play as “possibly too implausible.”

- Wucker (2016) gives the example of a detailed disaster plan provided by FEMA to Louisiana state officials in January 2005 based on a simulation of a Category 3 hurricane (“Hurricane Pam”) hitting southern Louisiana. When Hurricane Katrina hit in August 2005, most of the recommendations in that plan were not followed, and the plan was largely ignored.

- The UK government conducted major simulation exercises on a pandemic outbreak in 2007 (Winter Willow) and 2016 (Exercise Sygnus). However, a government inquiry on the government response to the COVID-19 pandemic found the focus of these exercises on an influenza pandemic left the country little prepared for coronavirus such as COVID-19. As noted by a previous Chief Medical Officer:

Quite simply, we were in groupthink. Our infectious disease experts really did not believe that SARS, or another SARS, would get from Asia to us. It is a form of British exceptionalism. . . .

We need to open up and get some more challenge into our thinking about what we are planning for. . . . In thinking through what could happen, it would be well worth bringing in people from Asia and Africa to think about that as well, to broaden our experience and the voices in the room. (UK House of Commons 2021, 20)

Thus, there is a need for risk assessment to be more than a tick-box exercise and instead, more of a form of management realignment. The use of scenario planning and “strategy as practice” are put forward as ways to achieve this (Linden 2021), as discussed later in this document.

Systematic Approaches for Addressing Shock Events in Airport Planning

Within the aviation sector, no methods for mitigating shock events specifically were uncovered during the research. However, approaches have been developed that address uncertainty generally which can apply to shock events. Much of these have been previously documented in ACRP Report 76 (Kincaid et al. 2012) and other publications and are summarized here, along with any updates to these approaches or new approaches that emerged.

A number of practitioners and researchers have proposed approaches to building more robustness to uncertainty in airport planning (or infrastructure planning generally). These include the following.

- Dynamic strategic planning (de Neufville and Odoni 2013).

- Flexible strategic planning (Burghouwt 2007).

- Dynamic adaptive planning (Walker et al. 2019).

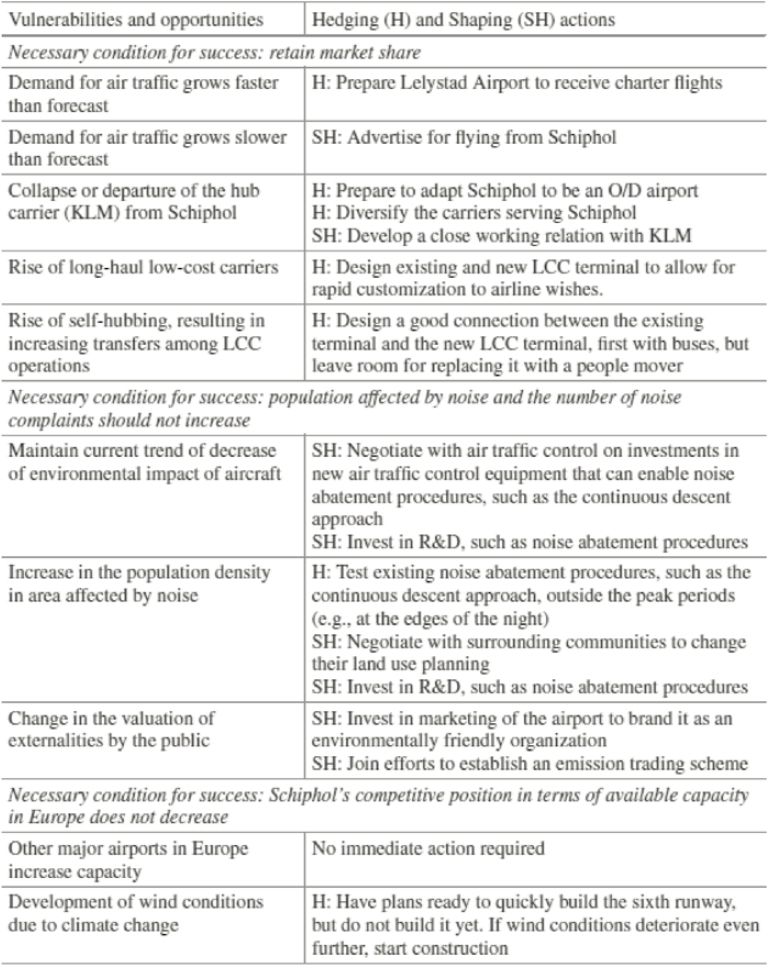

Although these approaches differ in methodology, the aim of each is to ensure that the airport’s planning (strategic planning as well as master planning) is flexible and adaptable to changes in market, political, social, regulatory, and technical conditions. Rather than focusing largely on a single forecast, these approaches consider a wider range of future scenarios and contingencies that can be built into the airport strategy and master planning. For example. Walker et al. (2019) provide an example of an application to Amsterdam Schiphol Airport (AMS), as shown in Figure 29.

While drawing on real-life experience, these approaches are largely theoretical and there is little evidence of them being formally applied by airports, although elements have been used in practice.

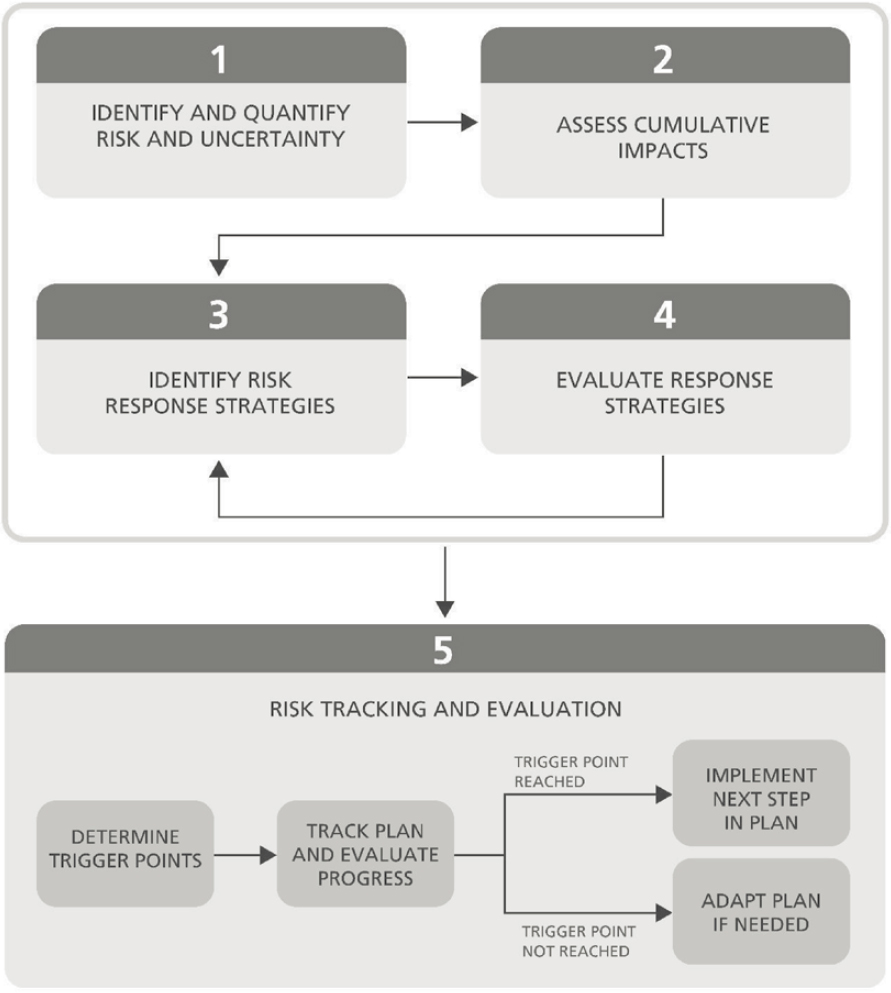

ACRP Report 76 (Kincaid et al. 2012) examined the issues of uncertainty generally in airport forecasting and planning. It put forward a systems analysis framework that draws on aspects of

Figure 29. Vulnerabilities and opportunities and proposed responses at AMS (Walker et al. 2019).

flexible planning, real options, and strategic planning under uncertainty. The systems analysis framework and related methodologies are designed to assist airport decision-makers with

- Identifying and characterizing risks (threats or opportunities), including their plausibility and magnitude;

- Assessing the impact of these threats and opportunities, i.e., determining what could happen, to which air facility, and when it might occur; and

- Developing response strategies to avoid or lessen the impact of threats or foster the realization of opportunities.

The framework and methodology involved five key steps as summarized in Figure 30. The framework allows planners to consider a broad range of events and risks; forecast or model these risks; and develop approaches to avoid, mitigate, or exploit these risks. It is designed to augment (rather than replace) existing strategic planning and master planning methodologies and

is scalable to the nature of the project and the resources of the airport. While the methodology did consider shock events, this was not a focus of the research, and the need for further research into shock events was acknowledged in the report.

The methodology set out in Part III to address shock events draws on some of the ideas and methodologies discussed in ACRP Report 76. As such, the shock events methodology can complement or augment the methodology set out in ACRP Report 76 and would fit within its framework. While the shock events methodology and this guide are designed to be stand-alone, readers are encouraged to also review ACRP Report 76 (Kincaid et al. 2012).

Practical Approaches for Airports to Address Shock Events

There are various strategies and actions airports can and do take to mitigate against uncertainty. While not specific to shock events, some of these apply to such events. Based on a review of previous research, observation of airports generally, and the experience of the research team, these strategies are summarized in Table 4 (this list is not exhaustive).

Supporting Airport Recovery with Revenue Diversification

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, airport operators were diversifying revenue sources to fund the maintenance of airport facilities, day-to-day operations, capital improvements, and changing demands for passenger services. The pandemic intensified the need for airport operators to address severe declines in activity, fluctuating passenger demand, and uncertainty about the paths for recovery. Much has been discussed about revenue strategies in previous research [notably, ACRP Report 121: Innovative Revenue Strategies—An Airport Guide (Kramer et al. 2015)]; however, a few ideas stand out as particularly germane in mitigating shock events.

- Airports balance keeping service provision in-house or contracting out to maximize revenues.

- Develop central processing in the terminal area for deliveries of food, beverages, and retail products and distribution of products to concessionaires.

- Operate baggage handling for airlines.

- Provide fuel storage and/or fueling services for airlines and private aircraft.

- Operate FBO.

- Manage gates, passenger check-in, and jet bridge operations.

- Airports engage in new activities and land uses through lease participation, direct ownership, public-private partnerships, or joint development.

- Expand electric power generation capacity, add charging stations, and establish pricing strategies.

- Partner with urban air mobility (UAM) companies for airport access and pretravel processing (UAM envisions a safe and efficient aviation transportation system that will use highly automated aircraft that will operate and transport passengers or cargo at lower altitudes).

- Develop gas plazas, convenience stores, restaurants, and personal services for air travelers or members of the community.

- Develop mineral estates or water resources if available.

- Build clean energy capacity for airport and community use.

- Position the airport as a testing ground for new technology and innovations, such as wildlife management, autonomous airport security, and UAM.

- Airports refine concession strategies to address what passengers want and need throughout the day in post-pandemic times.

- Expand market research using point-of-sale data for preordering food and preselecting parking spaces to gain knowledge about passenger preferences and segments.

Table 4. Airport-specific approaches to address uncertainty and shock events.

| Strategy | Comments |

|---|---|

| Land banking – reserving or purchasing land for future development. | Mitigates or hedges against the upside risk associated with strong traffic growth. The airport authority (or government) has the flexibility to expand and take advantage of high traffic growth, but they are not committed to doing so. |

| Reservation of terminal space – similar to land banking, this involves setting aside space within the terminal for future use (e.g., security processes). | Mitigates against high traffic growth or changes in traffic mix (e.g., from domestic to international or O/D to transfer). Also mitigates against changes in government policy or regulation (or the overall security environment). The space can be designed so that it remains productive in the short term (e.g., using it for retail that can be removed quickly). |

| Development of nonaeronautical revenues and ancillary activities | Revenue diversification (discussed in the next section) can also be an effective risk-mitigation strategy. Airports can engage directly (or partner with third parties) in nonaeronautical revenues to diversify their sources of income. By relying less on aircraft operations and passenger enplanements, airports can reduce the systemic revenue uncertainty associated with the air travel industry. However, diversification can expose the airport to greater risk from other sectors of the economy. |

| Air service development | Increase the range of carriers and routes operating at the airport using a diversification/hedging strategy, thereby reducing exposure to particular carriers or markets. |

| Shock event response plans | The development of response plans is a relatively low-cost way of enhancing robustness to shock events and has parallels with the approach already used by airports to respond to emergencies and accidents. |

| Stakeholder consultation | Helps ensure that stakeholders understand the airport’s plans and enables the airport to respond to concerns (e.g., an airline concerned that the airport is becoming too crowded). Also allows identification of additional risks (including lack of support from certain stakeholder groups). |

| Trigger points/thresholds –next stage of development goes ahead only if predetermined traffic levels are reached. |

Addresses both upside and downside risks and can be applied to specific traffic categories—for example,

|

| As many construction projects have long lead times (due to planning, construction, etc.), the trigger should be specified to allow for this lag. For example, the trigger to expand the terminal facilities may be when passenger volumes reach 90% of existing capacity, allowing time for the additional facilities to be built before the terminal reaches full capacity. | |

| This approach applies to not only capital developments. For example, a downside trigger could be determined for certain traffic markets, so if traffic falls below that level, additional air service development work would be undertaken. | |

| The trigger does not necessarily have to be traffic-based. For example, information from airport marketing might trigger actions or capital improvements to accommodate new air service. |

| Strategy | Comments |

|---|---|

| Modular or incremental development – building in stages as traffic develops. | Avoids airports committing to large capacity expansion when it is uncertain whether and how the traffic will develop. At the same time, an airport can respond to strong growth by incrementally adding modules. |

| Provides the flexibility to delay or accelerate expansion as traffic develops. Also mitigates against traffic mix changes; facilities designed to serve one traffic type can also be designed for incremental development. | |

| This option is closely linked to the trigger point concept described above. | |

| Linear terminal design and centralized processing facilities. | Allows the greatest flexibility for airport expansion since it is the most easily expandable in different directions (especially in combination with modular design). It also allows flexibility in the face of changing traffic mix (e.g., O/D vs. connecting). |

| Use of inexpensive, temporary buildings | Allows the airport to service one type of traffic (e.g., LCCs) while keeping options open to serve other types (e.g., full-service or transfer). Example: AMS’s LCC pier. |

| Non-load-bearing (or glass) walls – as with swing gates, terminal space can be converted from one use to another. | Avoids the airport being “locked in” to a narrow traffic development path, allowing greater flexibility to manage changes in traffic mix. Unlike swing gates, this is less short term in nature (not day-to-day). |

| Also allows broader flexibility in the overall function of the terminal, e.g., converting space from domestic to international, from retail to security, etc. | |

| Parametric design | Parametric design is the creation of a digital model of a building, such as a passenger terminal. Within that model are certain “parameters” reflecting key design attributes of the building. When one parameter is changed in the model using sophisticated algorithms and rules reset by the designer, it adjusts other attributes of the building to match. For example, changing the roof height will automatically change the walls, pillars, windows, and related elements. Parametric design allows for great flexibility as it is possible to quickly design a wide range of variants and test their robustness to various scenarios and objectives. |

| Common-use facilities and equipment – such as common-use terminal equipment (CUTE), common-use self-service (CUSS), common gates, lounges, and terminal space. | Mitigates against changes in the mix of traffic and carriers operating at the airport. Also has the benefit of reducing the overall space requirements of the terminal. |

| Swing gates or spaces – can be converted from domestic-to-international traffic (or between types of international traffic) on a day-to-day basis. | Mitigates against changes in traffic mix. Allows a very fine level of control, as it can allow adjustment to changes in traffic during the day as well as long-term developments. |

| Can also reduce overall space requirements as domestic and international traffic often peaks at different times of the day. | |

| Multiple apron ramp system (MARS) gates – the same gate can service one large aircraft or two smaller ones. | Mitigates against the uncertainty around the future mix of traffic (narrow-body vs. wide-body) and reduces the overall space requirements. |

| Tug-and-cart baggage systems | Provides much greater flexibility to make changes to the operation of the baggage system than does a fixed system. Mitigates against upside and downside traffic growth, traffic mix changes, and checked-baggage trends (e.g., less baggage due to checked-baggage charges). |

NOTE: Some of the information originally appeared in ACRP Report 76 (Kincaid et al. 2012), although additions and updates have been made.

-

- Develop gate delivery services for meals using centralized kitchens and ordering applications.

- Add vending machines for electronics and other e-commerce purchases.

- Use market data about time-of-day purchases and passenger segments to tailor the concession mix.

- Experiment with quick-change stands and pop-up-stations to target upcoming flight destinations and seasons.

- Build flexibility into contracts and leases to adjust commercial terms in the event of a pandemic or other business-stopping situations.

- Airports invest in automation to optimize contactless services and pricing strategies.

- Automate pretravel check-in and baggage handling with available customer service options for valet assistance.

- Use parking management systems to optimize revenue.

- Install autonomous airport security systems for airport perimeters and passenger clearance.

Planning and Design Techniques

Advancements in computing technology can aid in ensuring facility design provides flexibility and robustness to uncertainty. For example, the use of parametric design for buildings and structures allows for more design options to be considered and tested. Parametric design is the creation of a digital model of a building, such as a passenger terminal. Within that model are certain “parameters” reflecting key design attributes of the building. When one parameter is changed in the model using sophisticated algorithms and rules reset by the designer, it adjusts other attributes of the building to match. For example, changing the roof height will automatically change the walls, pillars, windows, and related elements. Parametric design allows for great flexibility as it is possible to quickly design a wide range of variants and test their robustness to various scenarios and objectives.

Technical Solutions

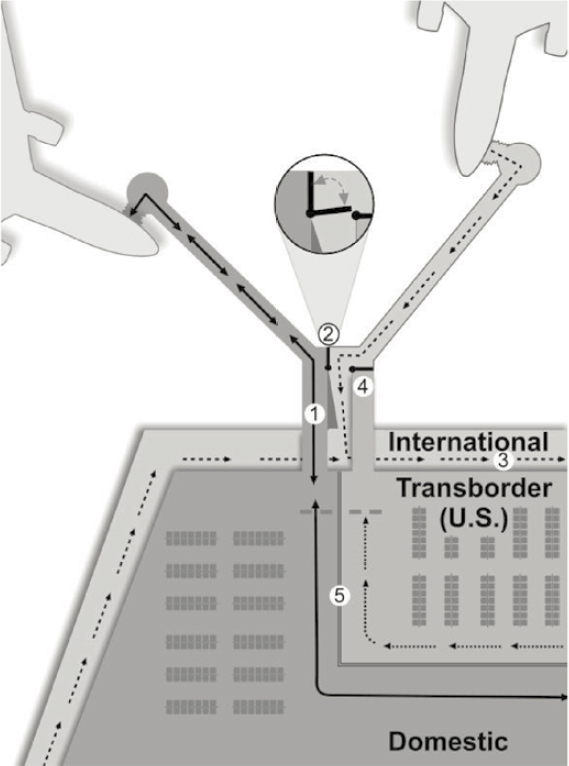

On the more technical side, the use of swing gates or multiple apron ramp system (MARS) gates not only mitigates the uncertainty around the future mix of traffic but can also reduce the overall space requirements if the peaks of different traffic segments occur at different times of the day. Figure 31 shows an example of a swing gate. The swing gate in this example can swing between three types of traffic: domestic, U.S., and international, as is required at some Canadian airports. Similarly, the MARS gate allows the same gate to handle two narrow-body aircraft or one wide-body aircraft, enhancing flexibility in the face of uncertain traffic and fleet development.

Developing robustness to uncertainty can also be applied to individual elements of the airport system. For example, ACRP Research Report 225: Rethinking Airport Parking Facilities to Protect and Enhance Non-Aeronautical Revenue (InterVISTAS 2021) put forward approaches for future-proofing parking developments at airports so they can adapt to changes in use or be converted to other uses. For example, sparse column grids and exterior ramps enable greater flexibility for how the airport can use the space as needs change in the future.

Insurance

Insurance is another means by which airports can mitigate shock events by transferring the risk to another party (at least partially). Many airports have business continuity or business interruption insurance. These typically insure airports against a loss of business due to facilities being damaged or out of action (e.g., due to a fire or hurricane). However, in the case of

COVID-19 there was no property damage and some of the airports interviewed during the project indicated that the insurance had exclusions for pandemics, communicable diseases, and “acts of God.” Thus, it is generally very difficult for airports to obtain insurance (or affordable insurance) for strategic risks such as a pandemic or loss of an air carrier.

It can be viewed that the federal government acted as insurer of last resort during the COVID-19 pandemic, through payments made to airports in the CARES Act and subsequent support measures.