Effects of Past Global Change on Life (1995)

Chapter: CONCLUSIONS

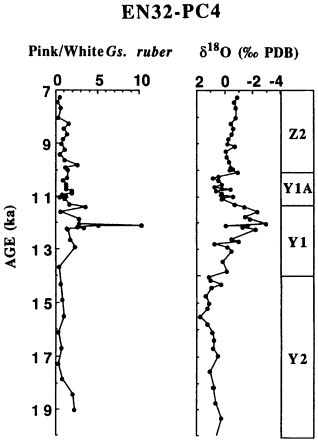

FIGURE 12.6 Percentage ratio (percent pink:percent white) for the pink and white varieties of Globigerinoides ruber is plotted for EN32-PC4 from the Orca Basin against 14C age, as discussed in text. Also shown are the d18O record (f) of Globigerinoides ruber (white variety) and foraminiferal subzones of Kennett and Huddlestun (1972). Subzones Y2, Y1, Y1A, and Z2 correspond to the late glacial, the meltwater spike, the Younger Dryas, and the early Holocene, respectively.

ruber during the meltwater spike also cannot be translated into temperature because of the low-salinity overprint. However, modern field observations (Hemleben et al., 1987) suggest that most planktonic foraminifera probably migrated to deeper waters below the relatively fresh surface waters that were perhaps colder.

The end of the low-salinity meltwater interval was marked by an important reappearance of cold-water forms characteristic of the last glacial episode. A brief reappearance of Gr. inflata occurs within a few centimeters in both cores and is dated at 11.4 ka. This species is today associated with the transition zone in the North Atlantic between the subtropical and subpolar surface water masses. Its reappearance in the Gulf of Mexico represents a major shift in the position of this boundary and is inferred to mark the onset of the Younger Dryas. The speed of the biotic response was remarkable, occurring in less than 200 yr.

The reappearance of Gr. inflata was followed by increased relative abundances of Gg. falconensis and decreased abundances of N. dutertrei, until about 10.2 ka. These changing abundances mark an interval between 11.4 and 10.2 ka of very cold, followed by cool, surface water conditions. The correspondence of this cool interval with the Younger Dryas centered in the North Atlantic region shows that oceanic cooling extended to the Gulf of Mexico. Its presence in the Gulf of Mexico (Kennett et al., 1985; Flower and Kennett, 1990; this chapter), the Sulu Sea (Linsley and Thunell, 1990; Kudrass et al., 1991), and the Gulf of California (Keigwin and Jones, 1990) suggests that expressions of the Younger Dryas occur throughout the Northern Hemisphere, if not worldwide.

The end of the Younger Dryas is marked by faunal and isotopic changes over less than 500 yr. Declining cool-water assemblages coincide with a decrease in d18O and are followed by increases in warm-water assemblages. The reappearance of consistent Gr. menardii, usually taken as marking the beginning of the Holocene, occurs at 9.8 ka. It is accompanied by large increases in Pu. obliquiloculata and N. dutertrei.

Further increases in the warm-water species Gr. menardii and Pu. obliquiloculata along with a decrease in the marginally warm-water species N. dutertrei occur at 5.5 ka and distinguish a warmer subzone in the late Holocene. This warmer late Holocene assemblage is not accompanied by any change in d18O of Gs. ruber, underlining the importance of independent faunal analysis in addition to geochemical methods in the investigation of paleoenvironmental change.

CONCLUSIONS

Oxygen isotopic and faunal analyses of high-resolution, radiometrically dated sediment sequences in the Gulf of Mexico demonstrate that planktonic foraminiferal communities were sensitive to deglacial environmental changes, including rapid temperature and salinity changes. Fossil assemblages reflect deglacial warming and low-salinity meltwater influx from the Laurentide ice sheet, the rapid onset and conclusion of the Younger Dryas, and stepwise warming into the Holocene. Rapid migrations characterized the dynamic response of oceanic biota and water masses in an area that amplified deglacial environmental change.

Warm-water planktonic foraminifera including Pulleniatina obliquiloculata and Neogloboquadrina dutertrei began to replace cold-water forms at 14 ka as the glacial species Globorotalia inflata disappeared in response to early deglacial warming. Simultaneously, the euryhaline