International Talent Programs in the Changing Global Environment (2024)

Chapter: Appendix F: Profiles of Foreign-Born Scientists

Appendix F

Profiles of Foreign-Born Scientists

KATALIN KARIKÓ

A Nobel Prize winner and pioneer in mRNA therapies who came to the United States from behind the Iron Curtain to perform research leading to the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine.

Katalin Karikó is a Hungarian-born biochemist whose research in ribonucleic acid (RNA) was critical to the development of the COVID-19 vaccine. Dr. Karikó and her colleague Drew Weissman were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2023 for their groundbreaking work in mRNA-based therapeutics. This accomplishment was due in part to Dr. Karikó’s ability to overcome adversity to live and work in the United States.

Dr. Karikó earned her bachelor’s degree in biology in 1978 at the University of Szeged, Hungary, where she began her work in RNA research. She received her doctorate in biochemistry in 1982 from the University of Szeged and worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the Biological Research Center of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The lab lost its funding in 1985, spurring Karikó to search for opportunities abroad. She was granted a postdoctoral position at Temple University and brought her husband, mother, and 2-year-old daughter with her to Philadelphia to begin her career as a foreign scientist in the United States (Kolata, 2021).

I never wanted to leave Hungary … but when it came time to apply for jobs, I knew I had to leave. – Katalin Karikó (Nair, 2021)

Karikó worked on Temple University’s biochemistry research team for 3 years. She was briefly employed by the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland, before accepting a nontenured professorship at the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school in 1989 (Nair, 2021). These early years were marked by struggle as she faced pressure to obtain grants or rely on colleagues with extra funding and navigated multiple immigration and visa-related issues. Karikó was pressured to give up her research on mRNA on multiple occasions; however, she persisted with this “impractical” line of research (Business Standard, 2023).

She was, in a positive sense, kind of obsessed with the concept of messenger RNA. – Anthony Fauci (Kolata, 2021)

New research collaborations and discoveries gradually followed, including the breakthroughs that mRNA could instruct cells to overproduce specific proteins and that mRNA could be modified to produce proteins without activating an immune response (Karikó et al., 1999, 2005). This culminated in Karikó joining German company Biopharmaceutical New Technologies (BioNTech) as a senior vice president in 2013. BioNTech licensed the mRNA technology earlier patented by Karikó and Weissman (Garde and Saltzman, 2020). Karikó lived full time in Germany, only visiting her husband and daughter in the United States for 2 months of the year (Johnson, 2021). In 2020, BioNTech partnered with Pfizer to develop an mRNA vaccine to the novel coronavirus using Karikó’s RNA-mediated mechanism.

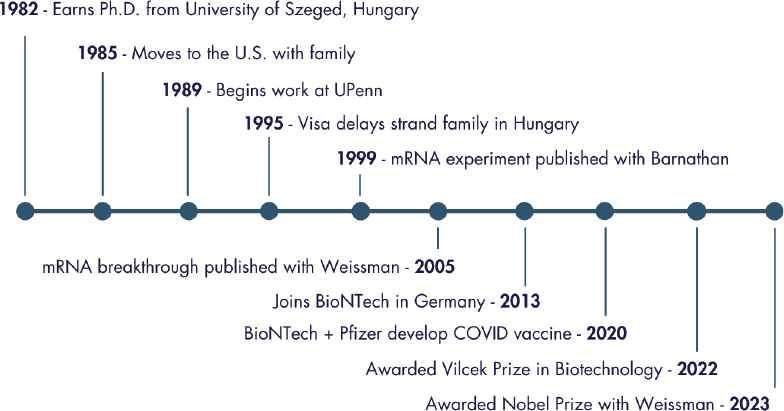

Karikó’s professional career spans long stretches of barely funded, understaffed research experiments that hopscotched multiple universities and labs—punctuated by multiple immigration-related concerns for both her and her family (see Figure F-1 for a timeline of these events). Had Karikó tried to move to the United States to conduct research today, she would be unlikely to have been able to do so given the current state of the U.S. immigration system (Neufeld, 2022a).

A thriving innovation ecosystem depends on the ability to draw on the world’s talent to work on groundbreaking and pressing problems. That ecosystem is at risk of withering as we’ve complacently let our immigration system collapse. What future crises will we be less prepared for because of current failures on our immigration system? – Jeremy Neufeld (Neufeld, 2022a)

TERENCE TAO

A distinguished mathematician whose intellect captivated the world since he was a precocious child in Australia.

Terence Chi-Shen Tao is an Australian-American mathematician described as “the Mozart of Math.” A child prodigy, Tao had obtained a bachelor’s and master’s degree in mathematics from Flinders University of South Australia by age 17 and was accepted into the Department of Mathematics Ph.D. program at Princeton University. He completed his doctorate at age 20 and immediately joined the faculty at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He was appointed as a full tenured professor of mathematics at UCLA less than less than 4 years later (Wolpert, 2006).

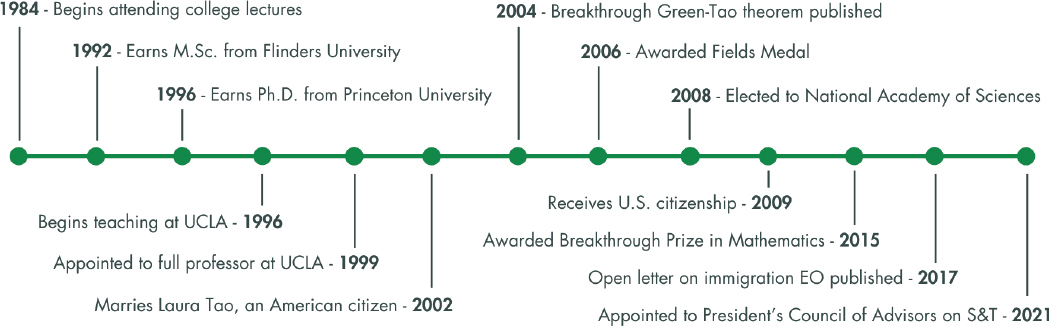

Tao’s work spans multiple complex mathematical branches, but he is best known for co-inventing the breakthrough Green-Tao theorem with Oxford mathematician Ben Green in 2004 (Wood, 2015). He has received myriad awards including the International Mathematical Union’s Fields Medal and a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship (Wolpert, 2019). Furthermore, Tao has consulted to U.S. government agencies in the areas of number theory, compressive sensing, and cryptography and currently serves as a member of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (see Figure F-2 for a timeline of these events) (K. Chang, 2007; White House, 2021; Wood, 2015).

To initially be hired as a tenure-track faculty member by UCLA, U.S. immigration officials granted Tao an O-1 visa, for individuals with extraordinary ability or achievement. UCLA submitted a petition to immigration authorities on Tao’s behalf along with written documented evidence of his extraordinary ability (Tao, 2003). The O-1 visa has many rigid renewal requirements and does not provide a pathway to permanent residency. To this end, Tao expressed in an open letter that he had struggled with U.S. immigration bureaucracy, including various glitches in the application and renewal of both his J-1 and O-1 visas (Tao, 2017). Tao ultimately was able to apply for permanent residency and U.S. citizenship after marrying his wife, a U.S. citizen (Tao, n.d.). He currently holds dual U.S. and Australian citizenship.

Talent is important, of course; but how one develops and nurtures it is even more so. – Terence Tao (Tao, 2024)

Tao has stated publicly that leading global mathematics departments actively recruit top mathematicians regardless of national origin. These institutions also will often retain counsel to ensure that such talent is able to obtain work authorization and residency. He has written about visa- and immigration-related provisions on his blog and advocated against Executive Order 13769 in 2017, arguing that this provision destroyed trust in the U.S. immigration system (Tao, 2017; Trump, 2017).

Mathematical research ability is highly non-fungible, and the value added by foreign students and faculty to a mathematics department cannot be completely replaced by an equivalent amount of domestic students and faculty, no matter how large and well educated the country. – Terence Tao (Tao, 2017)

MORRIS CHANG

An engineer, entrepreneur, and titan of industry who reshaped global trade with the invention of the foundry model of semiconductor manufacturing.

Morris Chang overcame humble beginnings in war-torn China— including foreign occupation and a civil war—to study engineering in the United States. By 1955, Chang held three degrees in mechanical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) (Dunn, 2013).

After leaving MIT, Chang pivoted into industry, accepting roles at Sylvania and Texas Instruments that had him working on transistors. His success in improving production yields for an IBM contract landed him a promotion and managerial role, in which he directed his own department of 20 engineers developing germanium transistors. In 1961, Chang entered a Ph.D. program at Stanford University, with his full salary and tuition paid for by Texas Instruments. Chang obtained U.S. citizenship in 1962, and a Ph.D. in electrical engineering from Stanford in 1964. He returned to Texas Instruments to oversee a department of 3,000 employees working on germanium transistors and was in charge of the company’s worldwide semiconductor business by 1972. After his career at Texas Instruments started to decline, Chang resigned and accepted the role of president and chief operating officer at General Instrument Corporation in 1984. However, he resigned this new role after 1 year due to differences in corporate strategy and vision (M. Chang, 2007; Perry, 2011).

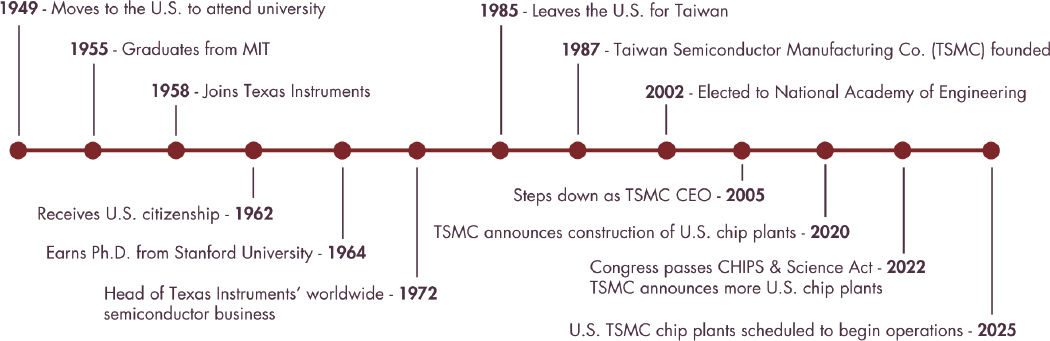

It was at this point, in 1985, that a Taiwanese government official reached out to Chang to manage the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI). Chang accepted, leaving the United States and moving to Taiwan to serve as president of ITRI. Shortly after, the Taiwanese official came to Chang with another proposal: to start a Taiwanese semiconductor company (Perry, 2011). Chang once again accepted, and in 1987, led the establishment of the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) that attracted contracts to produce semiconductors for companies that designed them (see Figure F-3 for a timeline of these events). This business model allowed companies to outsource chip production to TSMC, which was especially beneficial for smaller companies that otherwise would have had to direct significant resources to manufacturing capacity (Mozur and Liu, 2023). Year after year, as semiconductors became more complex and expensive to produce, Chang’s foundry model of semiconductor

manufacturing eliminated barriers to entry for many companies. TSMC outcompeted other chip manufacturers and attracted customers like Nvidia, whose breakthroughs in generative artificial intelligence were made possible by the large number of semiconductors it purchased. Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia, claims that his company would not exist without TSMC (Mozur and Liu, 2023).

The foundry model spearheaded by Chang has had far-reaching implications, influencing industries from consumer electronics to defense. Chang not only revolutionized the manufacturing and technology industries but also changed the global network of trade, played a role in Taiwan’s economic ascent, and fundamentally altered the global geopolitical and geoeconomic landscapes.

QIAN XUESEN

Deported from his adoptive country of the United States during the Second Red Scare, Qian invested in China, the country that invested in him, shaping the future of space exploration and national security.

Qian Xuesen (alternative spelling, Tsien Hsue-shen) was born in 1911, in the final year of China’s last imperial dynasty. He graduated from Shanghai Jiao Tong University in 1934 at the top of his class and came to the United States a year later to study aeronautical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on a Boxer Rebellion Indemnity Scholarship. In 1936, Qian transferred to the California Institute of Technology (BBC, 2020).

At Caltech, Qian studied at the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory under its director, Theodore Von Kármán. In 1943, after attracting research funding from the U.S. Army, Caltech established the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, with Von Kármán serving as its inaugural director. Qian was granted a security clearance to work on classified weapons research (Chang, 1995). He participated in the Manhattan Project, and his team provided the Army with a technical analysis of the German V-2 rocket program (Brown, 2009; Kivelson and Michelson, 2023; Jet Propulsion Laboratory, n.d.). In 1945, Qian moved to Washington, DC, to serve as a member of the Scientific Advisory Board to the Department of War. Upon achieving victory in Europe, the Pentagon sent Qian on a mission to Germany to inspect captured German military technology and interview Nazi rocket engineers, including Wernher Von Braun (BBC, 2020).

In 1947, Qian married in Shanghai, accepted a teaching position at MIT, and was granted permanent residency. Qian gave up his professorship to return to California in 1949 to accept a position as the first director of the Guggenheim Jet Propulsion Center at Caltech. He applied for U.S. citizens hip, but his application was denied (GALCIT, n.d.). In 1950, Qian was detained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation on charges of espionage and accused of being a member of an organization that advocated the overthrow of the U.S. government by force. The FBI was referring to an American Communist Party document that showed he attended what law enforcement officials believed to be a meeting of members at a Caltech scientist’s residence in 1938 (Fang, 2019). Qian denied the accusations, insisting that the event was an innocent social gathering. His colleagues,

including Von Kármán wrote to the U.S. government affirming his innocence (BBC, 2020). Nevertheless, his security clearance was revoked, and his naturalization application denied. Qian attempted to travel to China to visit his aging parents, but U.S. immigration officials apprehended and arrested him (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1955). He would spend the next 2 weeks in prison and the following 5 years under house arrest, only being able to continue teaching at Caltech in a limited capacity under strict supervision (Qiu, 2009).

Qian’s extended detention in the United States was a result of two conflicting orders against him: a deportation order and a travel ban. U.S. officials were concerned that Qian’s work in critical and sensitive areas might have compromised U.S. national security if he were allowed to leave (Fang, 2019). Officials in Washington, DC, lifted Qian’s exit ban in August 1955, as a part of the conditions for China’s releasing several U.S. prisoners of war (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1955). Qian’s deportation order was executed 1 month later. He departed the United States in September 1955 via an ocean liner accompanied by his wife and his two American-born children (Qiu, 2009). “I do not plan to come back,” he told reporters. “I have no reason to come back” (Atomic Heritage Foundation, n.d.).

It was the stupidest thing this country ever did. He was no more a communist than I was, and we forced him to go. – Dan Kimball (Osnos, 2009)

Arriving in Beijing, Qian was asked by government officials to create a missile program. His experience designing weapons and rockets for the United States became integral to China’s technological advancement. In 1956, he established the Institute of Mechanics in the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which later became a global leader in aeronautics education. He introduced policies that reshaped research and development processes and reformed the science and engineering training at Chinese universities (Qiu, 2009).

Qian personally trained the first generation of Chinese aerospace engineers, who in turn, created an industrial base for the design and production of rockets and weaponry. Chinese engineers completed construction on Dongfeng-2, a medium-range ballistic missile, in 1964. That same year, China tested their first nuclear weapon, and in 1966, the nation produced its first intercontinental ballistic missile capable of carrying a nuclear warhead (Qiu, 2009). In 1968, Qian became the director of the Chinese

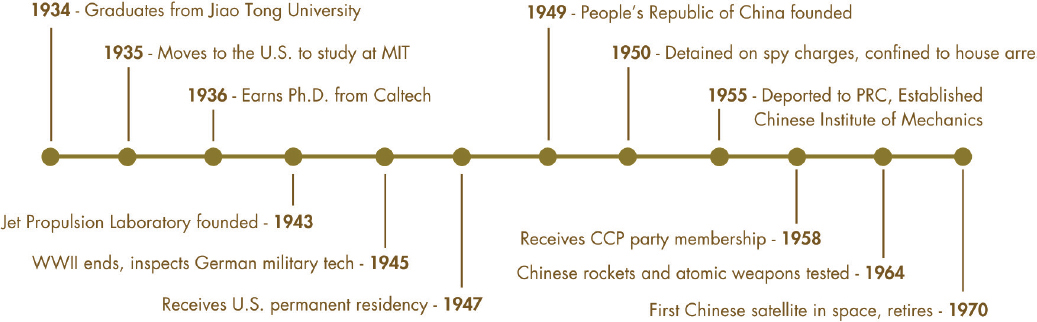

Academy of Space Technology. He retired in 1970, the same year China launched their first satellite into space on the Long March-1, a version of the Dongfeng ballistic missile adapted for space (see Figure F-4 for a timeline of events).

There was never any evidence produced that Qian engaged in espionage or transferred classified information to agents outside of the United States (BBC, 2020). Federal agents seized luggage Qian had intended to mail to his Shanghai address in 1950, later admitting that after searching the packages, they did not contain restricted materials (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1955). Qian’s contributions to the field of aeronautical engineering transformed the geopolitical landscape and lifted China into the atomic age. His contributions dubbed him “the father of Chinese rocketry” (Wines, 2009).

There is no evidence that Qian ever spied for China or was an intelligence agent when he was in the U.S. – Zuoyue Wang (Puri, 2020)

This page intentionally left blank.