Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra (2006)

Chapter: 2 The Father of Algebra

Chapter 2

THE FATHER OF ALGEBRA

§2.1 FROM EGYPT TO EGYPT: Diophantus,15 the father of algebra, in whose honor I have named this chapter, lived in Alexandria, in Roman Egypt, in either the 1st, the 2nd, or the 3rd century CE.

Whether Diophantus actually was the father of algebra is what lawyers call “a nice point.” Several very respectable historians of mathematics deny it. Kurt Vogel, for example, writing in the DSB, regards Diophantus’s work as not much more algebraic than that of the old Babylonians and Archimedes (3rd century BCE; see §2.3 below), and concludes that “Diophantus certainly was not, as he has often been called, the father of algebra.” Van der Waerden pushes the parentage of algebra to a point later in time, beginning with the mathematician al-Khwarizmi, who lived 600 years after Diophantus and whom I shall get to in the next chapter. Furthermore, the branch of mathematics known as Diophantine analysis is most often taught to modern undergraduates as part of a course in number theory, not algebra.

I shall give an account of Diophantus’s work and let you make your own judgment, offering my opinion on the matter, for what it is worth, as a conclusion.

§2.2 The people of Mesopotamia went on writing in cuneiform through centuries of ethnic and political churning, down to the region’s conquest by the Parthians in 141 BCE. We have mathematical texts in cuneiform from right up to that conquest. It is an astonishing thing, testified to by everyone who has studied this subject, that there was almost no progress in mathematical symbolism, technique, or understanding during the millennium and a half that separates Hammurabi’s empire from the Parthian conquest. The mathematician John Conway, who has made a study of cuneiform tablets, says that the only difference that presents itself to the eye is a “positional zero” marker in the latest tablets—a way, that is, to distinguish between, say, 281 and 2801. As with Mesopotamia, so with Egypt: We have no grounds for thinking that Egyptian mathematics made any notable progress from the 16th to the 4th century BCE.

If the mathematicians of Babylon and Egypt had made no progress in their homelands, though, their brilliant early discoveries had spread throughout the ancient West, and possibly beyond. From this point on—in fact, from the 6th century BCE—the story of algebra in the ancient world is a Greek story.

§2.3 The peculiarity of Greek mathematics is that prior to Diophantus it was mainly geometrical. The usual reason given for this, which sounds plausible to me, is that the school of Pythagoras (late 6th century BCE) had the idea to found all mathematics—and music, and astronomy—on number but that the discovery of irrational numbers so disturbed the Pythagoreans, they turned away from arithmetic, which seemed to contain numbers that could not be written, to geometry, where such numbers could be represented infallibly by the lengths of line segments.

Early Greek algebraic notions were therefore expressed in geometrical form, often very obscurely. Bashmakova and Smirnova, for example, note that Propositions 28 and 29 in Book 6 of Euclid’s great treatise The Elements offer solutions to quadratic equations. I

suppose they do, but this is not, to say the least of it, obvious on a first reading. Here is Euclid’s Proposition 28, in Sir Thomas Heath’s translation:

To a given straight line to apply a parallelogram equal to a given rectilineal figure and deficient by a parallelogrammic figure similar to a given one: thus the given rectilineal figure must not be greater than the parallelogram described on the half of the straight line and similar to the defect.

Got that? This, say Bashmakova and Smirnova, is tantamount to solving the quadratic equation x (a − x) = S. I am willing to take their word for it.

Euclid lived, taught, and founded a school in the city of Alexandria when it, and the rest of Egypt, was ruled by Alexander’s general Ptolemy (whose regnal dates as Ptolemy I are 306–283 BCE). Alexandria had been founded—by Alexander, of course—on the western edge of the Nile delta, looking across the Mediterranean to Greece, shortly before Euclid was born. Euclid himself is thought to have gotten his mathematical training in Athens, at the school of Plato, before settling in Egypt. Be that as it may, Alexandria in the 3rd century BCE was a great center of mathematical excellence, more important than Greece itself.

Archimedes, who was 40 years younger than Euclid, and who probably studied under Euclid’s successors in Alexandria, continued the geometric approach, though taking it into much more difficult terrain. His book On Conoids and Spheroids, for example, treats the intersection of a plane with curved two-dimensional surfaces of a sophisticated kind. It is clear from this work that Archimedes could solve certain particular kinds of cubic equations, just as Euclid could solve some quadratic equations, but all the language is geometric.

§2.4 Alexandrian mathematics went into something of a decline after the glory days of the 3rd century BCE, and in the disorderly 1st century BCE (think of Anthony and Cleopatra) seems to have died out altogether. With the more settled conditions of the early Roman imperial era, there was a revival. There was also a turn of thought away from purely geometrical thinking, and it was in this new era that Diophantus lived and worked.

As I intimated at the beginning of this chapter, we know next to nothing about Diophantus, not even the century in which he lived.

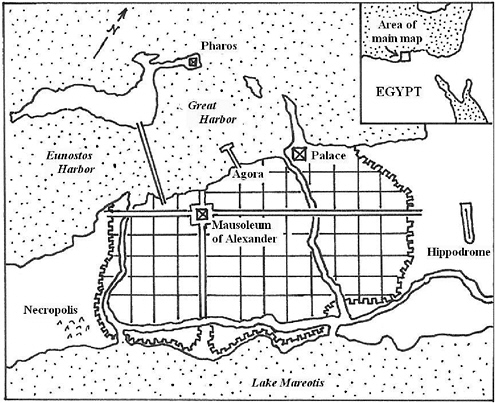

FIGURE 2-1 Ancient Alexandria. The Pharos was the famous lighthouse, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world, destroyed by a succession of earthquakes from the 7th century to the 14th. The great library is thought to have been in the vicinity of the palace, in the northeastern part of the city. The crenellated line shows the original (331 BCE) city walls.

The 3rd century CE is the most popular guess, with the dates 200–284 CE often quoted. Diophantus’s claim on our attention is a treatise he wrote, titled Arithmetica, of which less than half has come down to us. The main surviving part of the treatise consists of 189 problems in which the object is to find numbers, or families of numbers, satisfying certain conditions. At the beginning of the treatise is an introduction in which Diophantus gives an outline of his symbolism and methods.

The symbolism looks primitive to our eyes but was very sophisticated in its own time. An example will show the main points. Here is an equation in modern form:

Here it is as Diophantus writes it:

The easiest thing to pick out here is the numbers. Diophantus used the Greek “alphabetic” system for writing numbers. This worked by taking the ordinary Greek alphabet of 24 letters and augmenting it with three obsolete letters to give a total of 27 symbols. These were divided into three groups of nine each. The first nine letters of this augmented alphabet represented the digits from 1 to 9; the second nine represented the tens from 10 to 90; the third nine represented the hundreds from 100 to 900. The Greeks had no symbol for zero; neither did anyone else at this time.16

So in the equation I have shown, ![]() represents 1,

represents 1, ![]() represents 2,

represents 2, ![]() represents 10, and

represents 10, and ![]() represents 5. (The bars on the top are just to show that these letters are being used as numerals.)

represents 5. (The bars on the top are just to show that these letters are being used as numerals.)

Of the other symbols, ’íσ is short for ’íσoς, meaning “equals.” Note that there are no bars on top here; these are letters being used to spell a word (actually an abbreviation), not to represent numbers. The inverted trident, ![]() , indicates subtraction of everything that follows it, as far as the “equals sign.”

, indicates subtraction of everything that follows it, as far as the “equals sign.”

That leaves us with four symbols left to explain: KY, ς, ΔY, and ![]() . The second one, ς, is the unknown quantity, our modern x. The others are powers of the unknown quantity: KY the third power (from Greek

. The second one, ς, is the unknown quantity, our modern x. The others are powers of the unknown quantity: KY the third power (from Greek ![]() , a cube), ΔY the square (from

, a cube), ΔY the square (from ![]() , strength or power),

, strength or power), ![]() the zeroth power—what we would nowadays call “the constant term.”

the zeroth power—what we would nowadays call “the constant term.”

Armed with this knowledge, we can make a literal, symbol-for-symbol, translation of Diophantus’s equation as follows:

It makes a bit more sense if you put in the understood plus signs and some parentheses:

Since Diophantus wrote the coefficient after the variable, instead of before it as we do (that is, instead of “10x,” he wrote “x10”), and since any number raised to the power of zero is 1, this is equivalent to the equation as I originally wrote it:

It can be seen from this example that Diophantus had a fairly sophisticated algebraic notation at his disposal. It is not clear how much of this notation was original with him. The use of special symbols for the square and cube of the unknown was probably Diophantus’s own invention. The use of ς for the unknown quantity, however, seems to have been copied from an earlier writer, author of the so-called Michigan Papyrus 620, in the collection of the University of Michigan.17

Diophantus’s system of notation had some drawbacks, too. The principal one was that he could not represent more than one unknown. To put it in modern terms, he had an x but no y or z. This is a major difficulty for Diophantus, because most of his book (though not, as Gauss wrongly said, all of it), deals with indeterminate equations. This needs a little explanation.

§2.5 The word “equation” as mathematicians use it just means the statement that something is equal to something else. If I say “two plus two equals four,” I have stated an equation. Of course, the equations that mathematicians, including Diophantus, are interested in are ones with some unknown quantities in them. The presence of an unknown moves the equation from the indicative mood, “this is so,” to the interrogative, “is this so?” or, more often, “when is this so?” The equation

is implicitly a question: “What plus two equals four?” The answer is of course 2. This equation is so when x = 2.

Suppose, however, I ask this question:

What is the answer? We are now in deeper waters.

In the first place, a mathematician will immediately want to know what kind of answers you are seeking. Positive whole numbers only? Then the only solution is x = 1, y = 1. Will you settle for non-negative whole numbers (that is, including zero)? Now we have two more solutions: (a) x = 0, y = 2, and (b) x = 2, y = 0. Will you allow negative numbers as solutions? If you will, there is now an infinity of solutions—this one, for example: x = 999, y = −997. Will you allow rational numbers? If so, again there is an infinity of solutions, like this one: ![]() ,

, ![]() . And, of course, if you permit irrational numbers or complex numbers as solutions, then infinities pile upon infinities.

. And, of course, if you permit irrational numbers or complex numbers as solutions, then infinities pile upon infinities.

Equations of this sort, with more than one unknown in them and a potentially infinite number of solutions (depending on what kind of solutions are asked for), are called indeterminate.

The most famous of all indeterminate equations is the one that occurs in Fermat’s Last Theorem:

where x, y, z, and n must all be positive whole numbers. This equation

has an infinity of solutions if n = 1 or n = 2. Fermat’s Last Theorem states that it has no solutions when n is greater than 2.

Pierre de Fermat was reading Diophantus’s Arithmetica (in a Latin translation), around the year 1637, when the theorem occurred to him, and it was in the margin of this book that he made his famous note, stating the theorem, then adding (also in Latin): “Of which I have discovered a really wonderful proof, but the smallness of the margin cannot contain it.” The theorem was actually proved 357 years later, by Andrew Wiles.

§2.6 As I said, most of the Arithmetica consists of indeterminate equations. And, as I also said, this put Diophantus at a grave disadvantage, since he had a symbol for only one unknown (with those extra symbols for its square, cube, and so on).

To see how he got around this difficulty, here is his solution to the problem alongside which Fermat wrote that famous marginal note: Problem 8 in Book 2.

Diophantus states the problem: “A square number is to be decomposed into a sum of squares.” We should nowadays express this problem as: “Given a number a, find numbers x and y such that x2 + y2 = a2.” Diophantus, of course, did not have a notation as sophisticated as ours, so he preferred to spell out the problem in words.

To solve the problem, he begins by giving a a definite value, a = 4. So we are seeking x and y for which x2 + y2 = 16. He then writes y as an expression in x, the particular, though apparently arbitrary, expression y = 2x − 4. So now we have a specific equation to solve, one to which Diophantus could apply his literal symbolism:

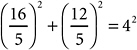

This is just a quadratic equation, and Diophantus knew how to solve it. The solution is ![]() . (There is another solution: x = 0. Diophantus, who had no symbol for zero, ignores this.) It follows that

. (There is another solution: x = 0. Diophantus, who had no symbol for zero, ignores this.) It follows that ![]() .

.

This does not look very impressive. In fact, it looks like cheating. The equation x2 + y2 = a2 has an infinity of solutions. Diophantus only got one. He got it by a procedure that can easily be generalized, though, and he knew—he says it elsewhere in his book—that there are infinitely many other solutions.

§2.7 I noted before that the first question in a mathematician’s mind when faced with an indeterminate equation like x + y + 2 = 4 is: What kind of solutions are you looking for? In Diophantus’s case the answer is positive rational numbers, like the ![]() and

and ![]() of the problem I worked out a moment ago. Negative numbers, along with zero, had not yet been discovered; Diophantus remarks of the equation 4x + 20 = 4 that it is “absurd.” He knows about irrational numbers, of course, but displays no interest in them. When they show up in a problem, he adjusts the terms of the problem to get rational solutions.

of the problem I worked out a moment ago. Negative numbers, along with zero, had not yet been discovered; Diophantus remarks of the equation 4x + 20 = 4 that it is “absurd.” He knows about irrational numbers, of course, but displays no interest in them. When they show up in a problem, he adjusts the terms of the problem to get rational solutions.

Seeking rational-number solutions to problems like the ones Diophantus tackled is really equivalent to seeking whole-number solutions to very closely related problems. The equality

is really

in thin disguise. So nowadays we use the phrase “Diophantine analysis” to mean “seeking whole-number solutions to polynomial equations.”

§2.8 Possibly the reader is still unimpressed by Diophantus’s attack on the equation x2 + y2 = a2. There seems to be remarkably little there to show for 2,000 years of mathematical reflection on the Babylonians’ solution of the quadratic equation and their other achievements.

In fairness to Diophantus, I should say that while that particular problem is a handy one to bring forward, he tackled much harder problems than that. The equation x2 + y2 = a2 illustrates his methods very well, it has that interesting connection with Fermat’s Last Theorem, and it doesn’t take long to explain; that is why it’s a popular example. Elsewhere Diophantus takes on cubic and quartic equations in a single unknown; systems of simultaneous equations in two, three, and four unknowns; and a problem equivalent to a system of eight equations in 12 unknowns.

Diophantus knew much more than is on display in his solution of x2 + y2 = a2. He knew the rule of signs, for example, stating it thus:

Wanting (that is, negativity) multiplied by wanting yields forthcoming (that is, positivity); wanting multiplied by forthcoming equals wanting.

This is a pretty remarkable thing, considering that, as I have already said, negative numbers had not yet been discovered!

In fact, that “not discovered” needs some slight qualification. While Diophantus had no notion of, let alone any notation for, negative numbers as independent mathematical objects and would not admit them as solutions, he actually makes free use of them inside his computations, for example, subtracting 2x + 7 from x2 + 4x + 1 to get x2 + 2x − 6. Clearly, even though he regarded −6 to be “absurd” as a mathematical object in its own right, he nonetheless knew, at some level, that 1 − 7 = −6.

It is situations like this that make us realize how deeply unnatural mathematical thinking is. Even such a basic concept as negative numbers took centuries to clarify itself in the minds of mathematicians, with many intermediate stages of awareness like this. Something similar happened 1,300 years later with imaginary numbers.

Diophantus also knew how to “bring a term over” from one side of an equation to the other, changing its sign as he did so; how to

“gather up like terms” for simplification; and some elementary principles of expansion and factorization.

His insistence on rational solutions also pointed into the far future, to the algebraic number theory of our own time. That equation x2 + y2 = a2 is, we would say nowadays, the equation of a circle with radius a. In seeking rational-number solutions to it, Diophantus is asking: Where are the points on that circle having rational-number coordinates x and y? That is a very modern question indeed, as we shall see much later (§14.4).

§2.9 So, was Diophantus the father of algebra? I am willing to give him the title just for his literal symbolism—his use of special letter symbols for the unknown and its powers, for subtraction and equality. The first time I saw one of Diophantus’s equations laid out in his own symbolism, my reaction was, as yours probably was: “Say what?” Looking through some of his problems, though, I quickly got used to it, to the degree that I could “read off” a Diophantine equation without much pause for thought.

At last I appreciated what a great advance Diophantus made with his literal symbolism. I do take Vogel’s point about the absence of general methods in the Arithmetica and am willing to take on faith Diophantus’s lack of originality in choice of topics. Probably it is also the case that he was not the first to deploy a special symbol for the unknown quantity.

Diophantus was, however, by the fortunes of history, the earliest to pass down to us such a widely comprehensive collection of problems so imaginatively presented. It is a shame we do not know who first used a symbol for the unknown, but since Diophantus used it so well, so early, we ought to honor him for that. Probably someone of whom we have no knowledge, nor ever will have any knowledge, was the true father of algebra. Since the title is vacant, though, we may as well attach it to the most worthy name that has survived from antiquity, and that name is surely Diophantus.