Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra (2006)

Chapter: 14 Algebraic This, Algebraic That

Chapter 14

ALGEBRAIC THIS, ALGEBRAIC THAT

§14.1 FROM ABOUT 1870—KLEIN’S Erlangen address forms a convenient milestone—the new understanding of algebra began to be applied all over mathematics. The new mathematical objects (matrices, algebras, groups, varieties, etc.) discovered by 19th-century algebraists began to be used by mathematicians in their work, as tools for solving problems in other areas of math—geometry, topology, number theory, the theory of functions. So far as geometry is concerned, I began to describe some of this spreading algebraicization in Chapter 13. Here I shall extend this coverage to algebraic topology, algebraic number theory, and the further progress of algebraic geometry through the late 19th and early to middle 20th centuries.

§14.2 Algebraic Topology. Topology is generally introduced as I described it in §AG.6, as “rubber-sheet geometry.” We imagine a two-dimensional surface—the surface of a sphere, say—to be made of some extremely stretchable material. Any other surface this rubber sphere can be transformed into by stretching or squeezing is “the same” as a sphere, so far as the topologist is concerned. There is some lawyering to be added to that, to make topology mathematically pre-

cise. You need some rules—which vary slightly in different applications—about cutting, gluing, “pinching off” a finite area into a dimensionless point, or allowing the surface to pass through itself as if the rubber were a kind of mist. The broad, familiar definition will suffice here, though.

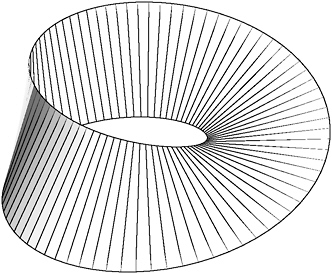

Topology did not actually have much to do with algebra until nearly the end of the 19th century. Its early development was, in fact, very slow. The word “topology” first began to be used in the 1840s by the Göttingen mathematician Johann Listing. Many of Listing’s ideas seem to have come from Gauss, with whom Listing was close. Gauss, however, never published anything on topology. In 1861, Listing described the one-sided surface we now call the Möbius strip (see Figure 14-1). Möbius wrote the thing up four years later, and for some reason it was his presentation that got mathematicians’ attention. It is much too late now to put things right, but I have labeled Figure 14-1 in a way that restores some tiny measure of justice. (If, by the way, you were to take the sphere-with-a-crease of my Figure AG-3 and cut out a small circular patch from it, what was left would be topologically equivalent148 to a Listing strip.)

FIGURE 14-1 A Listing strip.

Bernhard Riemann’s use of complicated self-intersecting surfaces to aid in the understanding of functions, presented in his 1851 doctoral thesis, was another factor in bringing topological ideas forward. Mulling over these Riemann surfaces, Camille Jordan (see §13.7) came up with the idea of studying surfaces—I am of course using the word “surfaces” here as a more easily visualizable substitute for “spaces”—by seeing what happens to closed loops embedded in them.

Imagine the surface of a sphere, for example. Pick a point on that surface. Starting from that point, walk around in a loop until you arrive back at the point. That path you have traced out: Can it, without having any un-topological violence done to it, and without ever leaving the surface, be shrunk right down to the starting point? Smoothly and continuously so shrunk? Yes, it can. So can any path on the surface of the sphere.

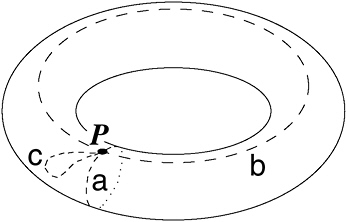

This is not so on the surface of a torus. Neither of the paths a or b drawn in Figure 14-2 can be shrunk down to the point P, though the path c can. So perhaps the study of these paths can indeed tell us something about the topology of a surface.

These ideas were algebraicized in 1895 by a brilliant French mathematician, Henri Poincaré at the École Polytechnique in Paris. Poincaré argued as follows. Consider all possible Jordan loops on a

FIGURE 14-2 Loops on a torus.

surface—all those paths you can traverse that begin and end at the same point. Holding that base point fixed, collect all the loops into families, two loops belonging to the same family if one can be smoothly deformed into the other—that is, is topologically equivalent to it. Contemplate these families, however many there might be. Define the following way of compounding two families: Traverse a path from the first family and then a path from the second. (It doesn’t matter which paths you choose.)

Here you have a set of elements—the loop-families—and a way to combine two elements together to produce another one. Could it be that these elements, these loop-families, form a group? Poincaré showed that yes, it could, and algebraic topology was born.

It is a short step from this—you need to get rid of dependence on any particular base point for your loops (and they do not, in point of fact, need to be precisely Jordan loops as I have defined them)—to the concept of a fundamental group for any surface. The elements of this group are families of paths on the surface; the rule for composition of two path-families is: First traverse a path from one family and then a path from the other.

The fundamental group of a sphere turns out to be the trivial group having only one element. Every loop can be smoothly deformed down all the way to the base point, so there is just one path-family.

The fundamental group of the torus, on the other hand, is a creature known as C∞ × C∞, which looks a bit alarming but really isn’t. Take the group elements to be all possible pairs of integers (m, n), with addition serving as the rule of composition: (m, n) + (p, q) = (m + p, n + q) The element (m, n) corresponds to going m times around the a path in Figure 14-5 and then n times round the b path. (If m is negative, you go in the opposite direction. It may help you to follow the argument here if you set off from the base point at an angle, then wind spirally round the torus m times before ending up back at the base point.) These integer pairs, with that simple rule of composition, form the group C∞ × C∞.149

I mentioned that the fundamental group for the surface of a sphere is the trivial group with only one member. This fact is itself far from trivial.

It turns out that any two-dimensional surface having the trivial one-member group as its fundamental group must be topologically equivalent to a sphere. Now, the familiar two-dimensional sphere-surface embedded in ordinary three-dimensional space has analogs in higher dimensions. There is, for example, a curved three-dimensional space “just like” a sphere but living in four dimensions—a hypersphere, it is sometimes called.150 Question: Is it also true in four dimensions that any three-dimensional curved space whose fundamental group is the trivial one-member group is topologically equivalent to this hypersphere?

The famous Poincaré conjecture, posed by Henri Poincaré in 1904, asserts that the answer is yes. At the time of this writing (late 2005), the conjecture has neither been proved nor disproved. It is probably true, and in a series of papers made available in 2002 and 2003, the Russian mathematician Grigory Perelman offered a proof that this is so. Mathematicians are still evaluating Perelman’s work as I write. Informal reports from these evaluations suggest a growing consensus that Perelman has, in fact, proved the conjecture. The Poincaré conjecture is one of the seven Millennium Prize Problems for the solution of which the Clay Mathematics Institute of Cambridge, Massachusetts, has offered $1 million each. If Perelman’s proof is indeed sound, he will therefore become $1 million richer.

When a mathematical theory begins to spawn conjectures, it has truly come alive. Topology came alive with Poincaré’s 1895 book, whose title was Analysis situs—“The Analysis of Position.” That is what topology had mostly been called for the first few decades of its existence, Listing notwithstanding. The use of “topology” to name this subject did not become universal until the 1930s, the credit belonging, I think, to Solomon Lefschetz, concerning whom I shall say more about in just a moment.

§14.3 There is a curious contradiction in Poincaré’s having been the founder of modern topology.

In the minds of mathematicians, topology actually comes in two flavors, the inspiration for one being geometry, for the other, analysis. I am using “analysis” here in the mathematical sense, as the branch of math that deals with functions, with limits, with the differential and integral calculus, above all with continuity. If you look back at my numerous mentions of smooth and continuous deformations, you will grasp the topological connections. In a sense, topology “can’t be made to work” without some underlying notion of smoothness, of continuity, of gliding in infinitely tiny increments from one place to another—some analytical way of thinking.

In mathematical jargon, the opposite of analytical is combinatorial. In combinatorial math we study things that can be tallied off, one! two! three!…, with nothing between the integers. Since there is no whole number between consecutive integers, there is no smooth path to take us from one to the next. We just have to leap over a void. Analytical math is legato, gliding smoothly through continuous spaces; combinatorial math is staccato, leaping boldly from whole number to whole number.

Now, topology ought to be the most legato of all mathematical studies, with its sheets of rubber flexing and stretching smoothly and continuously. And yet the very first topological invariant that ever showed up—it measures the number of doughnut-type holes in a surface and was discovered by Swiss mathematician Simon l’Huilier in 1813—is a whole number, as well as a hole number…. Dimension, which is another topological invariant (you can’t, topologically, turn a shoelace into a pancake, or a pancake into a brick), is also a whole number. Even those fundamental groups that Poincaré uncovered are not continuous groups, like Sophus Lie’s, but countable ones, as defined in §NP.3. Although they may be infinite, their members can be tallied: one, two, three, …. You can’t do that with the members of a continuous group. So everything of interest in topology seems to be staccato, not legato.

The paradox is that Poincaré came to topology via analysis, specifically via some problems he was studying in differential equations. Yet his results, and his whole cast of mind in Analysis situs, is combinatorial. The analytical approach to topology (the approach nowadays generally called point-set topology) had little appeal to him.

This same paradox was even more marked in Poincaré’s most important successor in algebraic topology, the Dutch mathematician L. E. J. Brouwer, whose dates were 1881–1966. It was actually Brouwer, in 1910, who proved that dimensionality is a topological invariant. Even more important in modern mathematics is his fixed-point theorem. Formally stated:

|

Brouwer’s Fixed-Point Theorem Any continuous mapping of an n-ball into itself |

An n-ball is just the notion of a solid unit disk (all points in the plane no more than one unit distant from the origin) or solid unit sphere (all points in three-dimensional space ditto), generalized to n dimensions. Two-dimensionally, the theorem means that if you send each point of the unit disk to some other point, in a smooth way—that is, points that are very close go to points that are also very close—then some one point will end up where it started.

The fixed-point theorem, together with some straightforward extensions, has many consequences. For instance: Stir the coffee in your cup smoothly and carefully. Some one (at least) point of the coffee—some molecule, near enough—will end up exactly where it started. (Note: Topologically speaking, the coffee in your cup is a 3-ball. By stirring it, you are sending each molecule of coffee from some point X in the 3-ball to some point Y. This is what we mean by “mapping a

space into itself.”) Even less obvious: Place a sheet of paper on the desk and draw around its outline with a marker. Now scrunch up the sheet, without tearing it, and put the scrunched-up paper inside the outline you marked. It is absolutely certain that one (at least) point of the scrunched-up paper is vertically above the point of the table that point rested on when the paper was flat and you were drawing the outline.151

The paradox lurking in Brouwer’s topology was that the results he obtained went against the grain of his philosophy. This would not matter very much to an ordinary mathematician, but Brouwer was a very philosophical mathematician. He was obsessed by metaphysical, or more precisely anti-metaphysical, ideas and with the work of finding a secure philosophical foundation for mathematics.

To this end, he developed a doctrine called intuitionism, which sought to root all of math in the human activity of thinking sequential thoughts. A mathematical proposition, said Brouwer, is not true because it corresponds to the higher reality of some Platonic realm beyond our physical senses yet which our minds are somehow able to approach. Nor is it true because it obeys the rules of some game played with linguistic tokens, as the logicists and formalists (Russell, Hilbert) of Brouwer’s time were suggesting. It is true because we can experience its truth, through having carried out some appropriate mental construction, step by step. The stuff of which math is made (to put it very crudely) is, according to Brouwer, not drawn from some storehouse in a world beyond our senses, nor is it mere language, mere symbols on sheets of paper, manipulated according to arbitrary rules. It is thought—a human, biological activity founded ultimately on our intuition of time, which is a part of our human nature.

That is the merest précis of intuitionism, which has generated a vast literature. Readers who know their philosophy will detect the influences of Kant and Nietzsche.152

Brouwer was not in fact the only begetter of this line of thinking, not by any means. Something like it can be traced all through the

modern history of mathematics, back before Kant and at least as far as Descartes. Sir William Rowan Hamilton, the discoverer of quaternions (Chapter 8), can be claimed for intuitionism, I think. His 1835 essay, “On Algebra as the Science of Pure Time,” attempts to bring over Kant’s idea—mainly based in geometry—of mathematics as founded on “intuition” and “constructions” into algebra.

Later in the 19th century, Leopold Kronecker objected bitterly, on grounds you could fairly call intuitionist avant la lettre, to Georg Cantor’s introduction of “completed infinities” into set theory. Kronecker argued that uncountable sets like ![]() do not belong in math—that math can be developed without them, that they bring unwanted and unnecessary metaphysical baggage into the subject, and that mathematics should be rooted in counting, algorithms, and computation.

do not belong in math—that math can be developed without them, that they bring unwanted and unnecessary metaphysical baggage into the subject, and that mathematics should be rooted in counting, algorithms, and computation.

It is this school of thought that Brouwer brought forward into the 20th century and transmitted to later mathematicians such as the American Errett Bishop (1928–1983). Brouwer’s version was called “intuitionism,” Bishop’s “constructivism.” It is as “constructivism” that these ideas are known nowadays, when their leading exponent in the United States is Professor Harold Edwards of the Courant Institute. Professor Edwards’s 2004 book, Essays in Constructive Mathematics, illustrates the approach very well (as, in fact, do his other books).

Professor Edwards argues that, with easy access to powerful computers, constructivism is now coming into its own and that, once everyone’s thinking has made the appropriate adjustments, much of the mathematics done from 1880 onward will come to seem misconceived. I am not qualified to pass judgment on this prediction, but I do personally, as a matter of temperament, find the constructivist approach very attractive and am a big fan of Professor Edwards’s writings, as can be seen from the numerous references to them in my text. My remarks on the making of mathematical models and the plotting of curves by hand in Chapter 13 are also very constructivist in flavor.

At any rate, Brouwer’s work in algebraic topology, done in his late 20s and early 30s must later have seemed to him philosophically

embarrassing. His fellow-countryman B. L. Van der Waerden, who studied under him in Amsterdam 10 years later, said the following in an interview with the Notices of the American Mathematical Society:

Even though his most important research contributions were in topology, Brouwer never gave courses on topology, but always on—and only on—the foundations of intuitionism. It seemed that he was no longer convinced of his results in topology because they were not correct from the point of view of intuitionism, and he judged everything he had done before, his greatest output, false according to his philosophy. He was a very strange person, crazy in love with his philosophy.

§14.4 Algebraic Number Theory. This is a phrase not easy to pin down. For one thing, there are objects called algebraic numbers, so that algebraic number theory might, in some context, mean the study of those objects. An algebraic number is a number that is a solution of some polynomial equation in one unknown with whole-number coefficients. Every rational number is algebraic: ![]() satisfies the equation 242x − 119 = 0. Any expression made up of rational numbers, ordinary arithmetic signs, and root signs, is also algebraic:

satisfies the equation 242x − 119 = 0. Any expression made up of rational numbers, ordinary arithmetic signs, and root signs, is also algebraic: ![]() satisfies the equation x14 − 36x7 + 313 = 0. It follows from Galois’ work, as I described it in §11.5, that a lot of equations of fifth and higher degree have solutions that can’t be expressed in that way, yet those solutions are algebraic too, by definition. Contrariwise, a lot of numbers are not algebraic, π being the best-known example. (Non-algebraic numbers are called transcendental. The first proof that π is transcendental was given by Ferdinand von Lindemann in 1882.) There is a large body of theory about these algebraic numbers, built on the foundations laid by Gauss and Kummer, the work I described in §§12.3–4. You can call that algebraic number theory, and mathematicians often do.

satisfies the equation x14 − 36x7 + 313 = 0. It follows from Galois’ work, as I described it in §11.5, that a lot of equations of fifth and higher degree have solutions that can’t be expressed in that way, yet those solutions are algebraic too, by definition. Contrariwise, a lot of numbers are not algebraic, π being the best-known example. (Non-algebraic numbers are called transcendental. The first proof that π is transcendental was given by Ferdinand von Lindemann in 1882.) There is a large body of theory about these algebraic numbers, built on the foundations laid by Gauss and Kummer, the work I described in §§12.3–4. You can call that algebraic number theory, and mathematicians often do.

Then again, modern algebraic concepts like “group” have proved very useful in tackling problems in traditional, general number theory. Notable among these problems has been the locating of rational points on elliptic curves. That sounds a bit formidable, but in fact the connection here goes straight back to Diophantus and his questions about finding rational-number solutions to polynomial equations like x3 = y2 + x (see §2.8). If you were to plot that equation as a graph of y against x, you would have what mathematicians call an elliptic curve. One of Diophantus’s solutions would correspond to a point on that curve whose x,y coordinates are rational numbers. Are there any such points? How many are there? How can I locate them? These questions may not sound exciting, but in fact they lead into a fascinating—quite addictive, in fact—area of modern math and to a great unsolved problem: the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture.153

Yet another topic within the scope of the term algebraic number theory is the discovery, just around the time that Poincaré was launching algebraic topology, of entirely new kinds of numbers, organized—as numbers should be!—in rings and fields. This branch of math was opened up by Kurt Hensel, who was born in Königsberg, David Hilbert’s hometown, just 25 days before Hilbert. Hensel studied mathematics under Kronecker in Berlin and then became a professor at Marburg in northwestern Germany, a position he held until his retirement in 1930. His importance to algebra lies in his discovery, around 1897, of p-adic numbers, a brilliant application of algebraic ideas to number theory.

The “p” in p-adic stands for any prime number, so I shall pick the value p = 5 for illustration. To begin with, forget about 5-adic numbers for a moment while I describe 5-adic integers. You probably know that there is a “clock arithmetic” associated with any whole number n greater than 1, an arithmetic in which only the numbers 0, 1, 2, …, n − 1 are used. If we take n = 12, for example, we have the ordinary clock face, but with the 12 erased and replaced by 0. If you add 9 to 7

on this clock (that is, if you ask the question: “What time will it be 9 hours after 7 o’clock?”), you get 4. In the usual notation,

Okay, write out the powers of 5:5, 25, 125, 625, 3125, 15625, …. Set up a clock for each of these numbers: a clock with hours from 0 to 4, one with hours from 0 to 24, one with hours from 0 to 124, and so on forever. Pick a number at random from the first clock face, say 3. Now pick a matching number at random from the second clock face. By matching, I mean this: the number has to leave remainder 3 after division by 5. So you can pick from 3, 8, 13, 18, and 23. I’ll pick 8. Now pick a matching number at random from the third clock face, a number that will leave remainder 8 after division by 25. So you can pick from 8, 33, 58, 83, and 108. I’ll pick 58. Keep going like this … forever. You have a sequence of numbers, which I’ll pack together into neat parentheses and call x. It looks something like this:

That is an example of a 5-adic integer. Note “integer,” not “number.” I’ll get to “number” in a minute. Given two 5-adic integers, there is a way to add them together, applying the appropriate clock arithmetic in each position. You can subtract and multiply 5-adic integers, too. You can’t necessarily divide, though. This sounds a lot like ![]() , the system of regular integers, in which you can likewise add, subtract, and multiply but not always divide. It is a ring, the ring of 5-adic integers. Its usual symbol is

, the system of regular integers, in which you can likewise add, subtract, and multiply but not always divide. It is a ring, the ring of 5-adic integers. Its usual symbol is ![]() 5.

5.

How many 5-adic integers are there? Well, in populating that first position in the sequence, I could choose from five numbers: 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4. Same for the second position, when I could choose from 3, 8, 13, 18, and 23. Same for the third, the fourth, and all the others. So the number of possibilities altogether is 5 × 5 × 5 × … forever. To put it crudely and—certainly from the Brouwerian point of view!—improperly, it is 5infinity.

What other set has this number? Consider all the real numbers between 0 and 1, and represent them in base 5 instead of the usual base 10. Here is the real number ![]() , for example, written in base 5:0.1243432434442342413234230322004230103420024…. Obviously, each position of such a “decimal” (I suppose that should be something like “quinquimal”) can be populated in five ways. Just like our 5-adic integers! So the number of 5-adic integers is the same as the number of real numbers between 0 and 1.

, for example, written in base 5:0.1243432434442342413234230322004230103420024…. Obviously, each position of such a “decimal” (I suppose that should be something like “quinquimal”) can be populated in five ways. Just like our 5-adic integers! So the number of 5-adic integers is the same as the number of real numbers between 0 and 1.

This is an interesting thing. Here we have created a ring of objects that behave like the integers, yet they are as numerous as the real numbers! In fact, there is a sensible way to define the “distance” between two 5-adic integers, and it turns out that two 5-adic integers can be as close together as you please—entirely unlike the ordinary integers, two of which can never be separated by less than 1. So these 5-adic integers are somewhat like the integers and somewhat like real numbers.

Now, just as with the ring ![]() of ordinary integers, you can go ahead and define a “fraction field”

of ordinary integers, you can go ahead and define a “fraction field” ![]() —the rational numbers—so with

—the rational numbers—so with ![]() 5 there is a way to define a fraction field

5 there is a way to define a fraction field ![]() 5 in which you can not only add, subtract, and multiply but also divide. That is the field of 5-adic numbers.

5 in which you can not only add, subtract, and multiply but also divide. That is the field of 5-adic numbers.

![]() 5, like

5, like ![]() 5, has a foot in each camp. In some respects it behaves like

5, has a foot in each camp. In some respects it behaves like ![]() , the rational numbers; in others it behaves like

, the rational numbers; in others it behaves like ![]() , the real numbers. Like

, the real numbers. Like ![]() , for instance, but unlike

, for instance, but unlike ![]() (or

(or ![]() 5), it is complete. This means that if an infinite sequence of 5-adic numbers closes in on a limit, that limit is also a 5-adic number. This is not so with every field. It is not so with

5), it is complete. This means that if an infinite sequence of 5-adic numbers closes in on a limit, that limit is also a 5-adic number. This is not so with every field. It is not so with ![]() , for example. Take this sequence of numbers in

, for example. Take this sequence of numbers in ![]() :

:

Each denominator is the sum of the previous numerator and denominator; each numerator is the sum of the previous numerator and twice the denominator. (So 29 = 17 + 12 and 41 = 17 + 12 + 12.) All the

numbers in that sequence are in ![]() , but the limit of the sequence is

, but the limit of the sequence is ![]() , which is not in

, which is not in ![]() .154 So

.154 So ![]() is not complete.

is not complete.

We can, however, complete ![]() by adding the irrational numbers to it:

by adding the irrational numbers to it: ![]() is the “completion” of

is the “completion” of ![]() . Or rather,

. Or rather, ![]() is a completion of

is a completion of ![]() . The p-adic numbers offer us other ways to complete

. The p-adic numbers offer us other ways to complete ![]() .

.

Prime numbers, rings and fields, infinite sequences and limits—here we have a mix of notions from number theory, algebra, and analysis. That is the beauty and fascination of p-adic numbers. They were carried forward into mid-20th-century math by Hensel’s student and eventual successor in the Marburg chair, Helmut Hasse. Hasse generalized the p-adic numbers by basing them not just on ordinary primes but on “primes” in more general number systems, like those in my primer on field theory and those developed by Gauss and Kummer in their work on factorization of complex and cyclotomic integers.

Hasse went from Marburg to Göttingen in 1934, and thereby hangs a tale. It had been in the previous year, 1933, that the Nazi Party had come to power in Germany. All the Jewish professors at Göttingen were obliged to leave, and many non-Jews who found the Nazis objectionable—I have already mentioned Otto Neugebauer in this context in §1.3—were also driven out or left in protest.

Under the racial classification system of the time, Hasse was not Jewish. Because he had a Jewish ancestor, however, he was not altogether racially “pure” either and so was ineligible for party membership. He seems not to have been at all anti-Semitic, but he was a strong German nationalist and supported Hitler’s nonracial policies.

After the resignation of Neugebauer, and then of his successor, Hermann Weyl (another Gentile, though with a part-Jewish wife), Hasse was made head of Göttingen’s Mathematical Institute. His motives seem to have been honestly nationalist—to keep German mathematics alive—and he was disliked by the Nazi functionaries he had to deal with, partly for being racially dubious and partly for his intellectual idealism, a quality not much in favor among National Socialists. However, he was dismissed from the university by the British

occupation forces following the defeat of Hitler in 1945 and, then in his late 40s, was faced with the necessity to rebuild his professorial career, a thing he did without complaint.

§14.5 Algebraic Geometry. I left algebraic geometry, in the form of “modern classical geometry,” under the care of early 20th-century Italian mathematicians such as Corrado Segre, Guido Castelnuovo, Federigo Enriques, and Francesco Severi. I noted that by the 1910s, geometry in this style was beginning to encounter a crisis of foundations, with awkward conundrums showing up, most of them related to “degenerate cases” of surfaces and spaces, analogous to those degenerate cases of the conics I described in §AG.3. By 1920 these conundrums had become sufficiently serious to stall further progress.

It was clear that algebraic geometry was in need of an overhaul to put the subject on a more solid foundation, as had been done with analysis in the 19th century by a succession of mathematicians from Cauchy to Karl Weierstrass. The overhaul of algebraic geometry in the 1930s and 1940s was likewise a joint effort by several mathematicians. The essence of it was the raising of geometry to a higher level of abstraction.

I have already mentioned Felix Klein’s Erlangen program, the idea of tidying up the mess of geometries that had proliferated in the 19th century—projective geometry, non-Euclidean geometry, Riemann’s geometry of manifolds (“curved spaces”), geometry done with complex-number coordinates—by using group as an organizing principle.

Once mathematicians, following Klein, began to think of the new geometries as a totality, as a single collection of ideas in need of organizing, they began to notice patterns and principles common to all geometries. The idea of making geometry perfectly abstract, without reference to any visualized points or lines in any particular space, took hold, and several mathematicians of the later 19th century—Moritz

Pasch (in Giessen, Germany), Giuseppe Peano (Turin, Italy), Hermann Wiener (Halle, Germany)—attempted this abstraction.

David Hilbert caught this bug in 1892, when he was still a Privatdozent at the University of Königsberg. He traveled to Halle with some colleagues to attend a lecture by Hermann Wiener, in which Wiener expounded on his method of abstraction for geometry. Returning to Königsberg, Hilbert’s party had to change trains at Berlin. While waiting in the Berlin station, they talked about Wiener’s ideas. Hilbert passed the following remark: “One must at all times be able to say ‘tables, chairs, and beer mugs’ in place of ‘points, straight lines, and planes’.”155 (Compare the remarks about algebra made by Peacock, Gregory, and De Morgan in 1830–1850, quoted in §10.1.)

Hilbert did not follow up this memorable apothegm with action for another six years, by which time he was installed as a professor at Göttingen. He then gave a series of lectures during the winter of 1898–1899, in which the traditional geometry of Euclid was derived from a clear, complete set of abstract rules, of axioms, like those I gave for groups in §11.4. The objects referred to by the axioms, said Hilbert, might be any objects at all, but he chose to speak of them as points, lines, and planes in order to preserve the clarity of his exposition. These lectures were printed up as a book with the title The Foundations of Geometry.

The book was widely read by mathematicians and was very influential. Hilbert’s own mathematics subsequently went off in other directions, but he often returned to geometry for brief visits. In the winter of 1920–1921 he gave a series of lectures called “Intuitive Geometry” in which he ranged more widely, but less abstractly, than in the 1898–1899 lectures. This series, too, was printed up as a book, Geometry and the Imagination, which still remains popular today.156

Hilbert’s axiomatic treatment of Euclid’s geometry was an inspiration to younger mathematicians. It was some years, however, before the way forward became clear. There were simply too many different viewpoints jostling for attention: Hilbert’s axiomatic approach; Klein’s group-ification program of 1872 and his reworking of topol-

ogy in 1895; Hilbert’s work on algebraic invariants (the Nullstellensatz and basis theorems); and, toiling steadily away in the background, the Italian geometers, taking the mid-19th-century approach to the study of curves, surfaces, and manifolds as far as it could be taken.

§14.6 Two names stand out from the crowd in the eventual reworking of algebraic geometry: Solomon Lefschetz and Oscar Zariski. Both were Jewish; both were born in the Russian empire, as it stood in the late 19th century.

Lefschetz was the older, born in 1884. Though Moscow was his birthplace, his parents were Turkish citizens, obliged to travel constantly on behalf of Lefschetz Senior’s business. Solomon was actually raised in France and spoke French as his first language. Of Brouwer’s generation, he made his name in algebraic topology, as Brouwer did. In fact, even more remarkably like Brouwer, Lefschetz has a fixed-point theorem named after him. He moved to the United States at age 21 and worked in industrial research labs for five years before getting his Ph.D. in math in 1911. One consequence of this industrial work was that he had both his hands burned off in an electrical accident. He wore prostheses for the rest of his life, covered with black leather gloves. When teaching at Princeton (from 1925), he would begin his day by having a graduate student push a piece of chalk into his hand. Energetic, sarcastic, and opinionated, he was something of a character—Sylvia Nasar’s book A Beautiful Mind has some stories about him. He summed up his own relevance to the history of algebra very vividly: “It was my lot to plant the harpoon of algebraic topology into the body of the whale of algebraic geometry.”

Fifteen years younger than Lefschetz, Oscar Zariski was born in 1899. This was a particularly bad time to be born in Russia—to be born Jewish anywhere in the Old World, in fact. The turmoil of World War I, the revolutions of 1917, German occupation, and the subsequent civil war eventually drove Zariski out of his homeland. In 1920 he went to Rome, where he studied under Guido Castelnuovo, a

leader of the Italian school of “modern classical” geometers. By this time Castelnuovo and his colleagues understood that their methods had taken them as far as they could go. Castelnuovo, in his mid-50s at this point, felt that it was time to pass the torch. He urged Zariski to study the topological approach of Lefschetz.

This was at the time in the mid-1920s when Mussolini and his fascists were tightening their grip on Italian public life. Zariski got his doctorate at Rome in 1925. Within a year or two it was plain that Italy was not going to be the refuge from turmoil he had hoped for. Lefschetz was in Princeton now, and Zariski, following Castelnuovo’s encouragement, had established a working friendship with him. With Lefschetz’s help, in 1927, Zariski got a minor teaching position at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Two years later he joined the faculty of that institution.

Through the late 1920s and early 1930s, Zariski worked away at bringing Lefschetz’s modern topological ideas to bear on the “modern classical” geometry he had learned from the Italians. The result of this was a book, Algebraic Surfaces, published in 1935.

In the course of writing and researching that book, though, Zariski came to realize that the way forward in algebraic geometry lay not through topology alone but through the axiomatic methods pioneered by Hilbert in Foundations of Geometry and applied to abstract algebra by Emmy Noether. (This idea that mathematics had reached a fork in the road was on the minds of many mathematicians in the late 1930s. It is the context for that remark by Hermann Weyl that I quoted in my Introduction.) Beginning in 1937, Oscar Zariski set himself the task of reworking the foundations of algebraic geometry.

Though by this time he had become an American mathematician, Zariski spent the 1945–1946 academic year as a visiting instructor at the University of São Paolo, Brazil. His duties there included giving one lecture course of three hours a week. Only one person attended these lectures, the slightly younger French mathematician André Weil.

Born in 1906, Weil, who was a pacifist as well as being Jewish, had fled from the European war to some teaching positions in the United States before taking a post in São Paolo at the same time as Zariski.157 He was an established and quite well-known mathematician—Zariski had actually met him at least twice before, at Princeton in 1937 and at Harvard in 1941. The year they spent together in São Paolo was, however, exceptionally productive for both of them.

Weil, like Zariski, had gotten the idea of reworking algebraic geometry using the abstract algebra of Hilbert and Emmy Noether. In particular, he worked to generalize the theory of algebraic curves, surfaces, and varieties so that its results would be valid over any base field—not just the familiar ![]() and (by this time)

and (by this time) ![]() of the “modern classical” algebraic geometers but also, for example, the finite number fields I described in my primer on field theory. That opened up a connection with the prime numbers and with number theory in general, and Weil’s work was fundamental to the algebraicization of modern number theory. Without it, Andrew Wiles’s 1994 proof of Fermat’s last theorem would have been impossible.

of the “modern classical” algebraic geometers but also, for example, the finite number fields I described in my primer on field theory. That opened up a connection with the prime numbers and with number theory in general, and Weil’s work was fundamental to the algebraicization of modern number theory. Without it, Andrew Wiles’s 1994 proof of Fermat’s last theorem would have been impossible.

The various streams of thought that arose in the 19th century were now about to flow together into a new understanding of geometry, one based in abstract algebra and incorporating themes from topology, analysis, “modern classical” ideas about curves and surfaces, and even number theory. Hilbert’s beer mugs and Emmy Noether’s rings, Plücker’s lines and Lie’s groups, Riemann’s manifolds and Hensel’s fields, were all brought together under a single unified conception of algebraic geometry. That was one of the grand achievements of 20th-century algebra, though by no means the only one—nor the least controversial.