Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra (2006)

Chapter: 7 The Assault on the Quintic

Chapter 7

THE ASSAULT ON THE QUINTIC

§7.1 I HAVE DESCRIBED HOW SOLUTIONS to the general cubic and quartic equations were found by Italian mathematicians in the first half of the 16th century. The next obvious challenge was the general quintic equation:

Let me remind the reader of what is being sought here. For any particular quintic equation, a merely numerical solution can be found to whatever degree of approximation is desired, using techniques familiar to the Muslim mathematicians of the 10th and 11th centuries. What was not known was an algebraic solution, a solution of the form

where the word “algebraic” in those brackets means “involving only addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and the extraction of roots (square root, cube root, fourth root, fifth root, …).” I had better specify, for the sake of completeness, that the bracketed expression should contain only a finite number of these operations. The expression for a solution of the general quartic, given in §CQ.7, is the kind of thing being sought here.

We now know that no such solution exists. So far as I can discover, the first person who believed this to be the case—who believed, that is, that the general quintic has no algebraic solution—was another Italian, Paolo Ruffini, who arrived at his belief near the very end of the 18th century, probably in 1798. He published a proof the following year. (Gauss recorded the same opinion in his doctoral dissertation of that same year, 1799, but offered no proof.) Then Ruffini published second, third, and fourth proofs in 1803, 1808, and 1813. None of these proofs satisfied his fellow mathematicians, insofar—and it was not very far—that they paid any attention to them. Credit for conclusively proving the nonexistence of an algebraic solution to the general quintic is generally given to the Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrik Abel, who published his proof in 1824.

For practically the entire 18th century, therefore, it was believed that the general quintic equation had an algebraic solution. To find that solution, though, must have been reckoned a problem of the utmost difficulty. By 1700 it had, after all, been 160 years since Lodovico Ferrari had cracked the quartic, and no progress on the quintic had been made at all. The kinds of techniques used for the cubic and the quartic had not scratched the quintic. Plainly some radically new ideas were needed.

The matter fell into neglect during the 17th and early 18th centuries. With the powerful new literal symbolism now available, the discovery of calculus, the domestication of complex numbers, and the accelerating growth of the theoretical sciences, there was a great deal of low-hanging fruit for mathematicians to pick. Well-tried and apparently intractable problems of no obvious practical application tend to lose their appeal under such circumstances. This was, remember, a quintessentially—if you will pardon the expression—pure-mathematical problem. Anyone who needed an actual numerical solution to an actual quintic equation could easily find one.

§7.2 The great Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler (pronounced “oiler”) first tackled the problem of the general quintic in 1732 while living in St. Petersburg, Russia. He did not get very far with it on that occasion, but 30 years later, while working for Frederick the Great in Berlin, he had another go. In this paper (“On the Solution of Equations of Arbitrary Degree”), Euler suggested that an expression for the solutions of an nth-degree equation might have the form

where α is the solution of some “helper” equation of degree n − 1, and A, B, C, … are some algebraic expressions in the original equation’s coefficients. Well and good, but how do we know that this helper equation of degree n − 1 can be found?

We don’t, and with that the greatest mathematical mind of the 18th century63 (counting Gauss as belonging to the 19th) let matters stand. Euler’s work was not without result, though. Abel’s 1824 proof of the unsolvability of the general quintic opens with a form for the solutions very much like that last expression above.

§7.3 In the odd way these things sometimes happen, the crucial insights first came not from the 18th century’s greatest mathematician but from one of its least.

Alexandre-Théophile Vandermonde, a native Frenchman in spite of his name, read a paper to the French Academy64 in Paris in November 1770, when he was 35 years old. He subsequently read three more papers to the academy (to which he was elected in 1771), and these four papers were his entire mathematical output. His main life interest seems to have been music. Says the DSB: “It was said at that time that musicians considered Vandermonde to be a mathematician and that mathematicians viewed him as a musician.”

Vandermonde is best known for a determinant named after him (I shall discuss determinants later); yet the determinant in question does not actually appear in his work, and the attribution of it to him

seems to be a misunderstanding. Vandermonde is altogether an odd, shadowy figure, like one of Vladimir Nabokov’s inventions. Later in life he became a Jacobin, an ardent supporter of the French Revolution, before his health failed and he died in 1796.

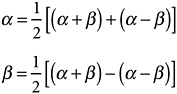

Vandermonde’s key insight was a way of writing each solution of an equation in terms of all the solutions. Consider, for example, the quadratic equation x2 + px + q = 0. Suppose its solutions are α and β. The following two things are obviously true:

To put it slightly differently: If you consider the square root sign to indicate two possible values, one plus and one minus, then the solutions of the quadratic equation are given by the two possible values of this expression:

What is the point of that? Well, (α − β)2 is equal to α2 − 2αβ + β2, which is equal to (α + β)2 − 4αβ, and that is a symmetric polynomial in α and β. Symmetric polynomials in the solutions, remember, can always be translated into polynomials in the coefficients, in this particular case p2 − 4q.

From this comes the familiar solution to the general quadratic equation. That, of course, is not the main point. The main point is that this approach looks like one that can be generalized to an equation of any degree, whereas previous approaches to the solutions of the quadratic, cubic, and quartic were all ad hoc and not generalizable.

Let’s generalize the above procedure to the depressed cubic equation x3 + px + q = 0. Using ω and ω2 for the complex cube roots of

unity as usual and recalling from §RU.3 that they satisfy the quadratic equation 1 + ω + ω2 = 0, I can write my general solution as

Since this is a depressed cubic, (α + β + γ) is zero (see §5.6), and we need only bother with the two cube root terms. It seems that there is a drawback here, though: The expressions under the cube root signs are not symmetric in α, β, and γ as the one under the square root sign was symmetric in α and β when I tackled the quadratic equation.

Let me investigate that a little more closely. I’ll put U = (α + ωβ + ω2γ)3, and V = (α + ω2β + ωγ)3. What happens to U and V under the six possible permutations of α, β, and γ? Well, denoting the permutations in a way that I hope is obvious:

|

Permutation |

U |

V |

|

α → α, β → β, γ → γ: |

(α + ωβ + ω2γ)3 |

(α + ω2β + ωγ)3 |

|

α → α, β → γ, γ → β: |

(α + ω2β + ωγ)3 |

(α + ωβ + ω2γ)3 |

|

α → γ, β → β, γ → α: |

(ω2α + ωβ + γ)3 |

(ωα + ω2β + γ)3 |

|

α → β, β → α, γ → γ: |

(ωα + β + ω2γ)3 |

(ω2α + β + ωγ)3 |

|

α → β, β → γ, γ → α: |

(ω2α + β + ωγ)3 |

(ωα + β + ω2γ)3 |

|

α → γ, β → α, γ → β: |

(ωα + ω2β + γ)3 |

(ω2α + ωβ + γ)3 |

(That first nothing-happens permutation is the “identity permutation.”)

This doesn’t look very informative. Remember, though, that ω is a cube root of unity. We can use this fact to “pull out” the ω and ω2 from in front of the α terms. For example, taking the first term in the fifth row:

which is just U. In fact, every one of those permutations works out to deliver either U or V. Half work out to U, half to V. The effect on U and V of any possible permutation of the solutions is either to leave U as U and V as V or to exchange U with V.

Let me just state that again, slightly differently, for effect. I tried all possible permutations of the solutions and found that half the permutations left U and V unchanged; the other half turned U into V and V into U.

The key concept here is symmetry. A polynomial in the solutions α, β, and γ may be totally symmetric, like the ones Viète and Newton investigated: Permute the solutions in all six possible ways and the value of the polynomial won’t change. It only has one value. Or a polynomial might be totally asymmetric: Permute the solutions in all six possible ways and the value of the polynomial will take six different values. Or, as in my example, the polynomial may be partially symmetric: Permute the solutions in all six possible ways and the value of the polynomial will take some number of values greater than 1 but less than 6.

Proceeding now to the solution: It follows from all this that any possible permutation of the solutions α, β, and γ will leave U + V and UV (or any other symmetric polynomial in U and V) unchanged. So U + V and UV must themselves be symmetric polynomials in the solutions α, β, and γ, and therefore they can be expressed in terms of the coefficients p and q of the cubic. In fact, if you chew through the algebra (and remember again that for a depressed cubic, α + β + γ, the coefficient of the x2 term, is zero), you will get

So if you solve the quadratic equation

for the unknown t, you shall have U and V. You have then solved the cubic. (Compare this approach with the one in §CQ.6.)

There is a second drawback to this method. As before, the root sign in that expression for a general solution is understood to embrace all possible values of the root—in this case, all three possible values of the cube root: a number, ω times that number, and ω2 times that number. Since there are two cube roots in my square brackets, the expression represents nine numbers altogether: the three solutions of my cubic and six other irrelevant numbers. How do I know which are which?

Vandermonde did not really overcome this problem. He had, though, introduced the key insight. In terms of the cubic:

Write a general solution in terms of a symmetric, or partially symmetric, polynomial in all the solutions.

Ask: How many different values can this polynomial take under all six possible permutations of α, β, and γ?

The answer is two, the ones I called U and V; this fact leads us to a quadratic equation.

This was the first attempt at solving equations by looking at the permutations of their solutions and at a subset of those permutations that left some expression—the cube of α + ωβ + ω2γ in my example—unchanged. These were key ideas in the attack on the general quintic.

§7.4 Alas for Vandermonde, his work was completely overshadowed by a much greater talent. Says Professor Edwards: “Unlike Vandermonde, who was French but did not have a French name, Lagrange had a French name but was not French.”65

Giuseppe Lodovico Lagrangia was born in Turin, in northwest Italy just 30 miles from the French border, in 1736. Though not French, he was of part-French ancestry and seems to have preferred writing in French, using the French form of his surname from an early age. (He spoke French with a strong Italian accent all his life,

however.) He became a member of the French Academy in 1787 and spent the rest of his life in Paris, dying there in 1813. He weathered the French Revolution and was instrumental in setting up the metric system of weights and measures. It is therefore not unjust that he is known to us as Joseph-Louis Lagrange. There is a pretty little park in Paris named after him; it contains the city’s oldest tree.66

Lagrange’s early working life was spent in Turin, where he was a professor of mathematics at age 16. By the time Vandermonde was presenting his paper to the French Academy in 1770, Lagrange had moved to Berlin, to the court of Frederick the Great. He was in fact Euler’s successor at that court, having arrived in 1766 as Euler left. Frederick apparently found Lagrange, who was well read in contemporary politics and philosophy and had a sly, ironic style of wit, much more gemütlich than the no-frills Euler and pronounced himself delighted with the change.

Lagrange’s great contribution to algebra came in 1771, a few months after Vandermonde’s presentation to the Academy in Paris. It was published by Frederick the Great’s own Academy, in Berlin, as a paper titled “Reflections on the Algebraic Solution of Equations.” It was this paper, by an already distinguished mathematician, that brought ideas about approaching equations via permutations of their solutions to the front of mathematicians’ minds.

It is all very unfair. Vandermonde thought of this first and is duly acknowledged in modern textbooks. His paper, however, went unnoticed and, according to Bashmakova and Smirnova, “had no effect on the evolution of algebra.” It was not even published until 1774, by which time Lagrange’s paper had been widely circulated. There is no evidence that Lagrange knew of Vandermonde’s work. He was not, in any case, a devious man and would have acknowledged that work if he had known about it. It was just a case of great minds—or more accurately, a great mathematical mind and a good one—thinking alike.

Lagrange followed the same train of thought as Vandermonde, but he was a stronger mathematician and took the argument further.

I shall stick with the general depressed cubic equation x3 + px + q = 0 by way of illustration.

Beginning with the same expression that Vandermonde had used, α + ωβ + ω2γ (it is technically known as the Lagrange resolvent), Lagrange noted that this takes six different values when you permute the solutions α, β, and γ, though its cube takes only two, as I showed above. The values are

As before, I can “pull out” the omegas from the α terms, using the fact that ω is a cube root of 1. Then, t3 = ω2t2, t4 = ωt2, t5 = ω2t1, and t6 = ωt1.

Now form the sixth-degree polynomial that has the t’s as its solutions. This will be

Lagrange calls it the resolvent equation. It easily simplifies to

which is the quadratic equation we got before, with solutions U = t13 and V = t23.

Lagrange carried out the same procedure for the general quartic, this time getting a resolvent equation of degree 24. Just as the resolvent for the cubic, though of degree 6, “collapsed” into a quadratic, so the degree-24 resolvent for the quartic collapses into a degree-6 equation. That looks bad, but the degree-6 equation in X turns out to actually be a cubic equation in X2, and so can be solved.

The number of possible permutations of five objects is 1 × 2 × 3 × 4 × 5, which is 120. Lagrange’s resolvent equation for the quintic therefore has degree 120. With some ingenuity, this can be collapsed into an equation of degree 24. There, however, Lagrange got stuck. He had, though, like Vandermonde, grasped the essential point: In order to understand the solvability of equations, you have

to investigate the permutations of their solutions and what happens to certain key expressions—the resolvents—under the action of those permutations.

He had also proved an important theorem, still taught today to students of algebra as Lagrange’s theorem. I shall state it in the terms in which Lagrange himself understood it. The modern formulation is quite different and more general.

Suppose you have a polynomial67 in n unknowns. There are 1×2×3×…×n ways to permute these unknowns. This figure, as you probably know, is called “the factorial of n” and is written with an exclamation point: n! So, 2! = 2, 3! = 6, 4! = 24, 5! = 120, and so on. (The value of 1! is conventionally taken to be 1. So, for deep but strong reasons, is 0!) Suppose you switch around the unknowns in all n! possible ways, as I did with α, β, and γ in the previous section. How many different values will the polynomial have? The answer in that previous section was 2, the values I called U and V. But what, if anything, can be said about the answer in general? If some polynomial takes A different values, is there anything we can say for sure about A?

Lagrange’s theorem says that A will always be some number that divides n! exactly. So form any polynomial you like in α, β, and γ, shuffle the three unknowns in all six possible configurations, and tally how many different values your polynomial takes. The answer will be 1, if your polynomial is symmetric. It may be 2, as was the case in my example up above. It may be 3, as in the case of this polynomial: α + β − γ. It may be 6, as with this one: α + 2β + 3γ. However, it will never be 4 or 5. That’s what Lagrange proved—though, of course, he proved it for any number n, not just n =3.

(Note that Lagrange’s theorem tells you a property of A: that it will divide n! exactly. It does not guarantee that every number that divides n! exactly is a possible A—a possible number of values for some polynomial to take on under the n! permutations. Suppose n is 5, for instance. Then n! is 120. Since 4 divides exactly into 120, you might expect that there exists some polynomial in five unknowns which, if you run the unknowns through all 120 possible

permutations, takes on four values. This is not so. The fact of its not being so was discovered by Cauchy, of whom I shall say more in the next section, and is critical to the problem of finding an algebraic solution to the general quintic.)

Lagrange’s theorem is one of the cornerstones of modern group theory—a theory that did not even exist in Lagrange’s time.

§7.5 The first name in this chapter was that of Paolo Ruffini, author of several attempts to prove there is no algebraic solution of the general quintic. Ruffini followed Lagrange’s ideas. For the general cubic equation we can get a resolvent equation that is quadratic, which we know how to solve. For a quartic equation, we can get a resolvent equation that is cubic, and we know how to solve cubics, too. Lagrange had shown that for an algebraic solution of the general quintic equation, we need to devise a resolvent equation that is cubic or quartic. Ruffini, by a close scrutiny of the values a polynomial can take when you permute its unknowns, showed that this was impossible.

“One has to feel desperately sorry for Ruffini,” remarks one of his biographers.68 Indeed one does. His first proof was flawed, but he kept working on it and published at least three more. He sent these proofs off to senior mathematicians of his day, including Lagrange, but was either ignored or brushed off with uncomprehending condescension—which must have tasted especially bitter coming from Lagrange, whom Italians considered a compatriot. Ruffini submitted his proofs to learned societies, including the French Institute (a replacement for the Academy, which had been temporarily abolished by the Revolution) and Britain’s Royal Society. The results were the same.

Almost until he died in 1822, poor Ruffini tried without success to get recognition for his work. Only in 1821 did any real acknowledgment come to him. In that year the great French mathematician Augustin-Louis Cauchy sent him a letter, which Ruffini must have treasured in the few months he had left. The letter praised his work

and declared that in Cauchy’s opinion Ruffini had proved that the general quintic equation has no algebraic solution. In fact, Cauchy had produced a paper in 1815 clearly based on Ruffini’s.69

I should pause here to say a word or two about Cauchy, since his name will crop up again in this story. It is a great name in the history of mathematics. “More concepts and theorems have been named for Cauchy than for any other mathematician (in elasticity alone there are sixteen concepts and theorems named for Cauchy).” That is from Hans Freudenthal’s entry on Cauchy in the DSB—an entry that covers 17 pages, the same number of pages as the entry for Gauss.

Cauchy’s style of work was very different from Gauss’s, though. Gauss published sparingly, only making known those results he had worked and polished to perfection. (This is why his publications are nearly unreadable.) It has been a standing joke with mathematicians for 150 years that when one has come up with a brilliant and apparently original result, the first task is to check that it doesn’t appear in Gauss’s unpublished papers somewhere. Cauchy, by contrast, published everything that came into his head, often within days. He actually founded a private journal for this purpose.

Cauchy’s personality has also generated much comment. Different biographers have drawn him as a model of piety, integrity, and charity, or as a cold-blooded schemer for power and prestige, or as an idiot savant, blundering through life in a state of unworldly confusion. He was a devout Catholic and a staunch royalist—a reactionary in a time when Europe’s intellectual classes were beginning to take up their long infatuation with secular, progressive politics.70

Modern commentary has tended to give Cauchy the benefit of the doubt on many issues once thought damning (though see §8.6). Even E. T. Bell deals evenhandedly with Cauchy: “His habits were temperate and in all things except mathematics and religion he was moderate.” Freudenthal inclines to the idiot-savant opinion: “[H]is quixotic behavior is so unbelievable that one is readily inclined to judge him as being badly melodramatic…. Cauchy was a child who was as

naïve as he looked.” Whatever the facts of the man’s personality, that he was a very great mathematician cannot be doubted.

§7.6 Under the circumstances, then, we should pity poor Ruffini and look with scorn on Niels Henrik Abel, to whom credit is commonly given for proving the algebraic unsolvability of the general quintic.

In fact, nobody thinks like that. For one thing, Cauchy’s opinion notwithstanding, mathematicians of his own time thought Ruffini’s proofs were flawed. (Modern views have been kinder to Ruffini, and the algebraic unsolvability of the general quintic is now sometimes called the Abel-Ruffini theorem.) For another the proofs were written in a style difficult to penetrate—this was Lagrange’s main problem with them. And for another, Abel is a person whose life presents a much more pitiable spectacle than Ruffini’s, though he seems to have been a cheerful and sociable man despite it all.

Abel was the first of the great trio of 19th-century Norwegian algebraists. We shall meet the other two later. He came from a place on the northern windswept fringes of Europe—near Stavanger, on the “nose” of Norway—poor in itself and made poorer and unhappier by the instability of the times. His own family belonged to the genteel poor. His father and grandfather were both country pastors. Abel’s father fell into political misfortune, took to drink, and “died an alcoholic, leaving nine children and a widow who also turned to alcohol for solace. After his funeral, she received visiting clergy while in bed with her peasant paramour.”71

For the rest of his short life—he died a few weeks before his 27th birthday—Abel was chronically hard up at the best of times and deep in debt at the worst. His country’s condition was similar. By the time Abel reached his teens, Norway was semi-independent as part of the joint kingdoms of Norway and Sweden, with a capital at Oslo, then called Christiania,72 and a parliament of her own, but living in the

economic and military shadow of the richer, more populous Sweden. It is to the Norwegians’ great credit that they scraped together enough funds to send this unknown young mathematician on a European tour from 1825 to 1827, though the meagerness of those funds and the vigilance with which their expenditure was supervised has aroused indignation in some of Abel’s biographers and seems to have inspired guilt in later Norwegian governments.

Abel had discovered mathematics very early and had had the good fortune to come under the guidance of a teacher, Bernt Michael Holmboë, who recognized his talent and who, though not a creative mathematician himself, knew his way around the major texts of the time. With Holmboë’s encouragement and financial help, Abel attended the new University of Christiania in 1821–1822.

Abel had already been working on the problem of the general quintic since 1820, had proved the unsolvability theorem, and in 1824 had paid from his own pocket to have the proof printed up. To save on expenses he condensed it to just six pages, sacrificing much of the proof’s coherence in the process. Still, he felt sure that those six pages would open the doors of Europe’s greatest mathematicians to him.

That was, of course, not quite what happened. The great Gauss, presented with a copy of Abel’s proof in advance of a visit from Abel in person, tossed it aside in disgust. This is not quite as shameful as it sounds. Gauss was already famous, and famous mathematicians, then as now, suffer considerably from the attention of cranks with claims to have proved some outstanding problem or other.73 Gauss was not a person who suffered fools gladly at the best of times, and he seems to have had little interest in the algebraic solution of polynomial equations. Abel canceled the planned visit to Gauss.

To make up for this disappointment, Abel had a great stroke of luck in Berlin. He met August Crelle, a unique figure in the history of math. Crelle—his dates are 1780–1855—was not a mathematician, but he was a sort of impresario of math. He had a keen eye for mathematical talent and excellence and, when he found it, did what he could to nourish it. Crelle was a self-made man and largely

self-educated, too, from humble origins. He got a job as a civil engineer with the government of Prussia and rose to the top of that profession. He was in part responsible for the first railroad in Germany, from Berlin to Potsdam, 1838. Sociable, generous, and energetic, Crelle played the barren midwife to great mathematical talents. He made a huge contribution to 19th-century math, though indirectly.

At just the time when Abel arrived in Berlin in 1825, Crelle had made up his mind to found his own mathematics journal. Crelle spotted the young Norwegian’s talent (they apparently conversed in French), introduced him to everyone in Berlin, and published his unsolvability proof in the first volume of his Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics in 1826. He published many more of Abel’s papers, too. The unsolvability of the quintic was merely one aspect, a minor one, of Abel’s wide-ranging mathematical interests. His major work was in analysis, in the theory of functions.

Abel returned penniless to Christiania in the spring of 1827 and died in 1829 from tuberculosis, the great curse of that age, without having left Norway again. Two days later, of course not knowing of Abel’s death, Crelle wrote to tell him that the University of Berlin had offered him a professorship.

Abel’s proof is assembled from ideas he picked up from Euler, Lagrange, Ruffini, and Cauchy, all mortared together with great ingenuity and insight. Its general form is of the type called reductio ad absurdum: that is, he begins by assuming the opposite of what he wants to prove and shows that this implies a logical absurdity.

What Abel wants to show is that there is no algebraic solution to the general quintic. He therefore begins by assuming that there is such a solution. He writes his general quintic like this:

Then he says: OK, let’s say there is an algebraic solution, all the solutions y being represented by expressions in a, b, c, d, and e, these expressions involving only a finite number of additions, subtractions, multiplications, divisions, and extractions of roots. Of course, the

root extractions might be “nested,” like the square roots under the cube roots in the solution of the general cubic. So let’s express the solutions in some general yet useful (for our purposes) way that allows for this nesting, in terms of quantities that might have roots under them, and under them, and under them….

Abel comes up with an expression for a general solution that closely resembles the one of Euler’s that I showed in §7.2. Borrowing from Lagrange (and Vandermonde, though Abel did not know that), he argues that this general solution must be expressible as a polynomial in all the solutions, along with fifth roots of unity, as in my §§7.3–7.4. Abel then picks up on the result of Cauchy’s that I mentioned at the end of §7.4: A polynomial in five unknowns can take two different values if you permute the unknowns, or five different values, but not three or four. Applying this result to his general expression for a solution, Abel gets his contradiction.74

§7.7 Abel’s proof—or, if you want to be punctilious about it, the Abel-Ruffini proof—that the general quintic has no algebraic solution, closes the first great epoch in the history of algebra.

In writing of the closing of an epoch, I am imposing hindsight on the matter. Nobody felt that way in 1826. In fact, Abel’s proof took some time to become widely known. Nine years after its publication, at the 1835 meeting of the British Association in Dublin, the mathematician G. B. Jerrard presented a paper in which he claimed to have found an algebraic solution to the general quintic! Jerrard was still pressing his claim 20 years later.

Nor did Abel’s proof put an end to the general theory of polynomial equations in a single unknown. Even though there is no algebraic solution to the general quintic, we know that particular quintics have solutions in roots. In my primer on roots of unity, for example, I showed exactly such a solution for the equation x5 − 1 = 0, which is indisputably a quintic. So the question then arises: Which quintic equations can be solved algebraically, using just +, −, ×, ÷, root signs,

and polynomial expressions in the coefficients? A complete answer to this question was given by another French mathematical genius, Évariste Galois, whose story I shall tell in Chapter 11.

There was, though, a great, slow shift in algebraic sensibility in the early decades of the 19th century. It had been under way for some time, since well before Abel printed up his six-page proof. I have characterized this new way of thinking as “the discovery of new mathematical objects.” Through the 18th century and into the beginning of the 19th, algebra was taken to be what the title of Newton’s book had called it: universal arithmetic. It was arithmetic—the manipulation of numbers—by means of symbols.

All through those years, however, European mathematicians had been internalizing the wonderful new symbolism given to them by the 17th-century masters. Gradually the attachment of the symbols to the world of numbers loosened, and they began to drift free, taking on lives of their own. Just as two numbers can be added to give a new number, were there not other kinds of things that might be combined, two such being merged together to give another instance of the same kind? Certainly there were. Gauss, in his 1801 classic Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, had dealt with quadratic forms, polynomials in two unknowns, like this:

His investigations led him to the idea of the composition of such forms, a way of melding two forms together to get a new one, more subtle than simple addition or multiplication of expressions. This was, wrote Gauss, “a topic no one has yet considered.”

And then there was Cauchy’s 1815 memoir on the number of values a polynomial can take when its unknowns are permuted. This was the memoir Abel had used in his proof. In it Cauchy introduces the idea of compounding permutations.

To give a simple illustration: Suppose I have three unknowns α, β, and γ, and suppose I refer to the switching of β and γ as permutation X, the switching of α and β as permutation Y. Now suppose I first

do permutation X and then permutation Y. What has happened? Well, permutation X turned (α, β, γ) into (α, γ, β). Then permutation Y turned this into (β, γ, α). So the net effect is to turn (α, β, γ) into (β, γ, α), which is another permutation! We could call it permutation Z, and speak of compounding permutation X and permutation Y to get permutation Z. That is in fact exactly how Cauchy did describe his manipulations, thereby essentially inventing the theory of groups (though he did not use that term).

In doing so Cauchy entered a strange new world. Note, for example, how the analogy between compounding permutations and adding numbers breaks down in an important respect. If you first do permutation Y and then permutation X, the result is (γ, α, β). So it matters which order you do your compounding in. This is not the case with addition of numbers, in which 7 + 5 is equal to 5 + 7. This particular property of ordinary numbers is technically known as commutativity. Cauchy’s compounding of permutations was noncommutative.

All of this was in the air in the early 19th century. After half a dozen generations of working with the literal symbolism of Viète and Descartes, mathematicians were beginning to understand that the compounding of numbers by addition and multiplication to get other numbers is only a particular case of a kind of manipulation that can be applied much more widely, to objects that need not be numbers at all. Those symbols they had gotten so used to might stand for anything: numbers, permutations, arrays of numbers, sets, rotations, transformations, propositions, … When this sank in, modern algebra was born.

§7.8 For the next few chapters I shall set aside a strictly chronological approach to my narrative. I have come to a period—the middle two quarters of the 19th century—of great fecundity in new algebraic ideas. Not only were groups discovered in those years, but also many other new mathematical objects. “Algebra” ceased to be

only a singular noun, and became a plural. The modern concepts of “field,” “ring,” “vector space,” and “matrix” took form. George Boole brought logic under the scope of algebraic symbolism, and geometers found that, thanks to algebra, they had many more than three dimensions to explore.

The historian of these fast-moving developments has two choices. He can stick to a strictly chronological scheme, trying to show how new ideas came up and interacted with others year by year, or he can follow one single train of thought through the period, then loop back and pick up another. I am going to take the latter approach, making several passes at this period of tumultuous growth in algebra and of radical changes in algebraic thinking. First, a trip into the fourth dimension.