Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra (2006)

Chapter: 8 The Leap into the Fourth Dimension

Chapter 8

THE LEAP INTO THE FOURTH DIMENSION

§8.1 MATHEMATICAL FICTION IS, TO PUT IT very mildly indeed, not a large or prominent category of literature. One of the very few such works to have shown lasting appeal has been Edwin A. Abbott’s Flatland, first published in 1884 and still in print today.

Flatland is narrated by a creature who calls himself “A Square.” He is, in fact, a square, living in a two-dimensional world—the Flatland of the book’s title. Flatland is populated by various other living creatures, all having two-dimensional shapes of various degrees of regularity: triangles both isosceles (only two sides equal) and equilateral (all three sides equal), squares, pentagons, hexagons, and so on. There is a system of social ranks, creatures with more sides ranking higher, and circles highest of all. Women are mere line segments and are subject to various social disabilities and prejudices.

The first half of Flatland describes Flatland and its social arrangements. Much space is given over to the vexing matter of determining a stranger’s social rank. Since a Flatlander’s retina is one-dimensional (just as yours is two-dimensional), the objects in his field of vision are just line segments, and the actual shape of a stranger—and therefore his rank—is best determined by touch. A common form of introduction is therefore: “Let me ask you to feel Mr. So-and-so.”

In the book’s second half, A Square explores other worlds. In a dream he visits Lineland, a one-dimensional place, of which the author gives an 11-page description. Since a Linelander can never get past his neighbors on either side, propagation of the species presents difficult problems, which Abbott resolves with great delicacy and ingenuity.

A Square then awakens to his own world—that is, Flatland—where he is soon visited by a being from the third dimension: a sphere, who has a disturbing way of poking more or less of himself into Flatland, appearing to A Square as a circle mysteriously expanding and contracting. The sphere engages A Square in conversations of a philosophical kind, at one point introducing him to Pointland, a space of zero dimensions, inhabited by a being who “is himself his One and All, being really Nothing. Yet mark his perfect self-contentment, and hence learn this lesson, that to be self-contented is to be vile and ignorant, and that to aspire is to be blindly and ignorantly happy.” I think we have all met this creature.

Abbott was not quite 46 years old when Flatland was published. The 240-word entry under his name in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica describes him as “English schoolmaster and theologian.” It does not mention Flatland. Abbott was actually a boys school headmaster of a reforming and progressive cast of mind, inspired by a personal view of Christianity and skeptical of many of the conventions of Victorian society. Flatland was written secondarily as mild social satire.

In the 120-odd years since its publication, Flatland has caught the attention and stirred the imagination of countless readers. It has, in fact, generated a subgenre of spinoff books and stories. Dionys Burger’s Sphereland and Ian Stewart’s Flatterland are noteworthy elaborations on Abbott’s original idea. The physics, chemistry, and physiology of two-dimensional existence—matters on which Abbott is light and not very convincing—were most brilliantly explored by A. K. Dewdney in his 1984 book The Planiverse.75 Of lower literary quality, but sticking in the mind somehow, is Rudy Rucker’s short

story “Message Found in a Copy of Flatland,” whose protagonist actually encounters Flatland in the basement of a Pakistani restaurant in London. He ends up eating the Flatlanders, who have “a taste something like very moist smoked salmon.”76

Spaces of zero, one, two, and three dimensions—why stop there? Probably most nonmathematicians first heard about the fourth dimension from H. G. Wells’s 1895 novel The Time Machine, whose protagonist says this:

Space, as our mathematicians have it, is spoken of as having three dimensions, which one may call Length, Breadth, and Thickness, and is always definable by reference to three planes, each at right angles to the others. But some philosophical people have been asking why three dimensions particularly—why not another direction at right angles to the other three?—and have even tried to construct a Four-Dimensional geometry.

Now, it takes a while for abstruse theories to seep down into popular literature, even today.77 If literary gents in the 1880s and 1890s were writing popular works about the number of dimensions space might or might not have, we can be sure that professional mathematicians must already have been pondering such questions among themselves for decades.

So they were. Ideas about the dimensionality of space were occurring to mathematicians here and there all through the second quarter of the 19th century. In the third quarter these occasional raindrops became a shower, allowing the great German mathematician Felix Klein (1849–1925) to make the following observation in hindsight: “Around 1870 the concept of a space of n dimensions became the general property of the advancing young generation [of mathematicians].”

Where did these ideas come from? There is no trace of them at the beginning of the 19th century. At the end of that century they are

so widely known as to be showing up in popular fiction. Who first thought of them? Why did they appear at this particular time?

§8.2 During the early decades of the 19th century, mature ideas about complex numbers “settled in” as a normal part of the mental landscape of mathematicians. The modern conception of number, as I sketched it at the beginning of this book, was more or less established in mathematicians’ minds (though the “hollow letters” notation I have used is late 20th century).

In particular, the usual pictorial representations of the real and complex numbers as, respectively, points spread out along a straight line, and points spread out over a flat plane, were common knowledge. The tremendous power of the complex numbers, their usefulness in solving a vast range of mathematical problems, was also widely appreciated. Once all this had been internalized, the following question naturally arose.

If passing from the real numbers, which are merely one-dimensional, to the complex numbers, which are two-dimensional, gives us such a huge increase in power and insight, why stop there? Might there not be other kinds of numbers waiting to be discovered—hyper-complex numbers, so to speak—whose natural representation is three-dimensional? And might those numbers not bring with them a vast new increase in our mathematical understanding?

This question had popped up in the minds of several mathematicians—including, inevitably, Gauss—since the last years of the 18th century, though without any very notable consequences. Around 1830, it occurred to William Rowan Hamilton.

§8.3 Hamilton’s life78 makes depressing reading. It is not that his circumstances were wretched in any outward way—marred by war, poverty, or sickness. Nor are there even any signs of real mental illness—chronic depression, for instance. Nor did he suffer from pro-

fessional neglect or frustration—he was already famous in his teens. It is rather that Hamilton’s life followed a downward trajectory. As a child he was a sensational prodigy; as a young man, merely a genius; in middle age, only brilliant; in his later years, a bore and a drunk.

Of Hamilton’s mathematical talents there can be no doubt. He was possessed of great mathematical insight and worked very hard to bring that insight to bear on the most difficult problems of his day. Today mathematicians honor him and revere his memory.

Born in Dublin of Scottish parents, Hamilton is claimed by both Ireland and Scotland, but he spoke of himself as an Irishman. He was a child prodigy, accumulating languages until, at age 13, he claimed to have mastered one for each year of his age.79 In the fall of 1823, he went up to Trinity College, Dublin, where he soon distinguished himself as a classics scholar. At the end of his first year, however, he met and fell in love with Catherine Disney.80 Her family promptly married her off to someone more eligible, and this lost love blighted Hamilton’s life and perhaps Catherine’s too. Hamilton later (in 1833) married, more or less at random, a sickly and disorderly woman and suffered all his life from an ill-managed household.

Hamilton had picked up math in his teen years, quickly mastering the subject, and graduated from Trinity with the highest honors in both science and classics—an achievement previously unheard of. In his final year he came up with his “characteristic function,” the ultimate source of the Hamiltonian operator so fundamental to modern quantum theory.

In 1827, Hamilton was appointed professor of astronomy at Trinity. Like all young mathematicians of his time, Hamilton was struck by the elegance and power of the complex numbers. In 1833, he produced a paper treating the system of complex numbers in a purely algebraic way, as what we should nowadays call “an algebra,” in fact. For the complex number a + bi, Hamilton just wrote (a, b). The rule for multiplying complex numbers now becomes

and the fact that i is the square root of minus one is expressed by

This may seem trivial, but that is because 170 years of mathematical sophistication stand between Hamilton and ourselves. In fact, it shifted thinking about complex numbers from the realms of arithmetic and analysis, where most mathematicians of the early 19th century mentally located them, into the realm of algebra. It was, in short, another move to higher levels of abstraction and generalization.

Hamilton now, from 1835 on, embarked on an eight-year quest to develop a similar algebra for bracketed triplets. Since passing from the one-dimensional real numbers to the two-dimensional complex numbers had brought such new riches to mathematics, what might not be achieved by advancing up one further dimension?

Getting a decent algebra out of number triplets proved to be very difficult, though. Of course, you can work something out if your conditions are loose enough. Hamilton knew, though, that for his triplets to be anything like as useful as complex numbers, their addition and multiplication needed to satisfy some rather strict conditions. They needed, for example, to obey a distributive law, so that if T1, T2, and T3 are any triplets, the following thing is true:

They also needed, like the complex numbers, to satisfy a law of moduli. The modulus of a triplet (a, b, c) is ![]() . The law says that if you multiply two triplets, the modulus of the answer is the product of the two moduli.

. The law says that if you multiply two triplets, the modulus of the answer is the product of the two moduli.

Hamilton fretted over this problem—the problem of turning his triplets into a workable algebra—more or less continuously through those eight years. During that time he acquired three children and a knighthood.

The mathematical conundrum was resolved for Hamilton with a flash of insight. He told the story himself, at the end of his life, in a letter to his second son, Archibald Henry:

Every morning in the early part of [October 1843], on my coming down to breakfast, your (then) little brother, William Edwin, and yourself, used to ask me, “Well, papa, can you multiply triplets?” Whereto I was always obliged to reply, with a sad shake of the head: “No, I can only add and subtract them.”

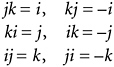

But on the 16th day of the same month—which happened to be Monday, and a Council day of the Royal Irish Academy—I was walking in to attend and preside, and your mother was walking with me along the Royal Canal, to which she had perhaps driven; and although she talked with me now and then, yet an undercurrent of thought was going on in my mind which gave at last a result, whereof it is not too much to say that I felt at once the importance. An electric circuit seemed to close; and a spark flashed forth the herald (as I foresaw immediately) of many long years to come of definitely directed thought and work by myself, if spared, and, at all events, on the part of others if I should even be allowed to live long enough distinctly to communicate the discovery. Nor could I resist the impulse—unphilosophical as it may have been—to cut with a knife on a stone of Brougham Bridge, as we passed it, the fundamental formula with the symbols i, j, k:

which contains the Solution of the Problem, but, of course, the inscription has long since mouldered away.

The insight that came upon Hamilton that Monday by Brougham Bridge81 was that triplets could not be made into a useful algebra, but quadruplets could. After the step from one-dimensional real numbers a to two-dimensional complex numbers a + bi, the next step was not to three-dimensional super-complex numbers a + bi + cj but to four-dimensional ones a + bi + cj + dk. By dint of some simple rules for multiplying i, j, and k, rules like those Hamilton inscribed on Brougham Bridge, these could be made into an algebra. Van der Waerden, in his History of Algebra, calls this inspiration “the leap into the fourth dimension.”

§8.4 To make this new algebra work, Hamilton had to violate one of the fundamental rules of arithmetic, the rule that says a × b = b × a. I have already mentioned, in relation to Cauchy’s compounding of permutations (§7.7), that this is known as commutativity. The rule a × b = b × a is the commutative rule. It is familiar to all of us in ordinary arithmetic. We know that multiplying 7 by 3 will give the same result as multiplying 3 by 7. The commutative rule applies just as well to complex numbers: Multiplying 2 − 5i by −1 + 8i will give the same result as multiplying −1 + 8i by 2 − 5i (38 + 21i in both cases).

Quaternions can only be made to work as an algebra, though—as a four-dimensional vector space with a useful way to multiply vectors—if you abandon this rule. In the realm of quaternions, for example, i × j is not equal to j × i; it is equal to its negative. In fact,

It was this breaking of the rules that made quaternions algebraically noteworthy and Hamilton’s flash of insight one of the most important revelations of that kind in mathematical history. Through all the evolution of number systems, from the natural numbers and fractions of the ancients, through irrational and negative numbers, to the complex numbers and modular arithmetic that had exercised the great minds of the 18th and early 19th centuries, the commutative rule had always been taken for granted. Now here was a new system of what could plausibly be regarded as numbers, in which the commutative rule no longer applied. The quaternions were, to employ modern terminology, the first noncommutative division algebra.82

Every adult knows that when you have broken one rule, it is then much easier to break others. As it is in everyday life, so it was with the development of algebra. In fact, Hamilton described quaternions to a mathematical friend, John Graves, in a letter dated October 17, 1843. By December, Graves had discovered an eight-dimensional algebra, a

system of numbers later called octonions.83 To make these work, though, Graves had to abandon yet another arithmetic rule, the associative rule for multiplication, the one that says a × (b × c) = (a × b) × c.

This, it should be remembered, was just the time when the non-Euclidean geometries—“curved spaces”—of Nikolai Lobachevsky and János Bolyai were becoming known. (I shall say more about this in §13.2.) Kant’s notion that the familiar laws of arithmetic and geometry are inbuilt, immutable qualities of human thought were slipping away fast. If such fundamental arithmetic principles as the commutative and associative rules might be set aside, what else might? If four dimensions were needed to make quaternions work, who was to say that the world might not actually be four-dimensional?84 Or that there might be creatures somewhere living in a two-dimensional Flatland?

§8.5 As brilliant as Hamilton’s insight was, it was only one of a number of occurrences of four-dimensional thinking at around the same time. The fourth dimension, and the fifth, the sixth, and the nth dimensions too, were “in the air” in the 1840s. If the 1890s were the Mauve Decade, the 1840s were, at any rate among mathematicians, the Multidimensional Decade.

In that same year of 1843, in fact, the English algebraist Arthur Cayley, whom we shall meet again in the next chapter, published a paper titled “Chapters of Analytic Geometry of n-Dimensions.” Cayley’s intention was, as his title says, geometrical, but he used homogeneous coordinates (which I shall describe in my primer on algebraic geometry), and this gave the paper a strongly algebraic flavor.

In fact, homogeneous coordinates had been thought up by the German astronomer and mathematician August Möbius, who had published a classic book on the subject, The Barycentric Calculus, some years before. Möbius seems to have understood at that time that an irregular three-dimensional solid could be transformed into its mirror-image by a four-dimensional rotation. This—the date was

1827—may actually be the first trace of the fourth dimension in mathematical thinking.

The mention of Möbius here leads us to the Germans. Though these years were great ones for British algebraists, across the channel there was already swelling that tidal wave of talent that brought Germany to the front of the mathematical world and kept her there all through the later 19th and early 20th centuries.

§8.6 There was at that time a schoolmaster in the Prussian city of Stettin (now the Polish city of Szczecin) named Hermann Günther Grassmann. Thirty-four years old in 1843, he had been teaching in a gymnasium (high school, roughly) since 1831. He continued to teach school until nearly the end of his life. He was self-educated in mathematics; at university he had studied theology and philology. He married at age 40 and fathered 11 children.

The year after Hamilton’s discovery, Grassmann published a book with a very long title beginning Die lineale Ausdehnungslehre…—“The Theory of Linear Extensions…” In this book—always referred to now as the Ausdehnunsglehre (pronounced “ows-DEHN-oongz-leh-reh”)—Grassmann set out much of what became known, 80 years later, as the theory of vector spaces. He defined such concepts as linear dependence and independence, dimension, basis, subspace, and projection. He in fact went much further, working out ways to multiply vectors and express changes of basis, thus inventing the modern concept of “an algebra” in a much more general way than Hamilton with his quaternions. All this was done in a strongly algebraic style, emphasizing the entirely abstract nature of these new mathematical objects and introducing geometrical ideas as merely applications of them.

Unfortunately, Grassmann’s book went almost completely unnoticed. There was just one review, written by Grassmann himself! Grassmann, in fact, belongs with Abel, Ruffini, and Galois in that sad company of mathematicians whose merit went largely unrecognized

by their peers. In part this was his own fault. The Ausdehnungslehre is written in a style very difficult to follow and is larded with metaphysics in the early 19th-century manner. Möbius described it as “unreadable,” though he tried to help Grassmann, and in 1847 wrote a commentary praising Grassmann’s ideas. Grassmann did his best to promote the book, but he met with bad luck and neglect.

A French mathematician, Jean Claude Saint-Venant, produced a paper on vector spaces in 1845, the year after the Ausdehnungslehre appeared, showing ideas similar to some of Grassmann’s, though plainly arrived at independently. After reading the paper, Grassmann sent relevant passages from the Ausdehnungslehre to Saint-Venant. Not knowing Saint-Venant’s address, though, he sent them via Cauchy at the French Academy, asking Cauchy to forward them. Cauchy failed to do so, and six years later he published a paper that might very well have been derived from Grassmann’s book. Grassmann complained to the Academy. A three-man committee was set up to determine whether plagiarism had occurred. One of the committee members was Cauchy himself. No determination was ever made….

The Ausdehnungslehre did not go entirely unread. Hamilton himself read it, in 1852, and devoted a paragraph to Grassmann in the introduction to his own book, Lectures on Quaternions, published the following year. He praised the Ausdehnungslehre as “original and remarkable” but emphasized that his own approach was quite different from Grassmann’s. Thus, nine years after the book’s publication, precisely two serious mathematicians had noticed it: Möbius and Hamilton.

Grassmann tried again, rewriting the Ausdehnungslehre to make it more accessible and publishing a new edition of 300 copies in 1862 at his own expense. That edition contains the following preface, which I find rather moving:

I remain completely confident that the labor I have expended on the science presented here and which has demanded a significant

part of my life as well as the most strenuous application of my powers, will not be lost. It is true that I am aware that the form which I have given the science is imperfect and must be imperfect. But I know and feel obliged to state (though I run the risk of seeming arrogant) that even if this work should again remain unused for another seventeen years or even longer, without entering into the actual development of science, still that time will come when it will be brought forth from the dust of oblivion and when ideas now dormant will bring forth fruit. I know that if I also fail to gather around me (as I have until now desired in vain) a circle of scholars, whom I could fructify with these ideas, and whom I could stimulate to develop and enrich them further, yet there will come a time when these ideas, perhaps in a new form, will arise anew and will enter into a living communication with contemporary developments. For truth is eternal and divine.

The 1862 edition fared little better than the 1844 one had, however. Disillusioned, Grassmann turned away from mathematics to his other passion, Sanskrit. He produced a massive translation into German of the Sanskrit classic Rig Veda, with a lengthy commentary—close to 3,000 pages altogether. For this work he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Tübingen.

The first major mathematical advance based directly on Grassmann’s work came in 1878, the year after his death, when the English mathematician William Kingdon Clifford published a paper with the title “Applications of Grassmann’s Extensive Algebra.” Clifford used Grassmann’s ideas to generalize Hamilton’s quaternions into a whole family of n-dimensional algebras. These Clifford algebras proved to have applications in 20th-century theoretical physics. The modern theory of spinors—rotations in n-dimensional spaces—is descended from them.

§8.7 The 1840s thus brought forth two entirely new mathematical objects, even if they were not understood or named as such by their

creators: the vector space and the algebra. Both ideas, even in their early primitive states, created wide new opportunities for mathematical investigation.

For practical application, too. These were the early years of the Electrical Age. At the time of Hamilton’s great insight, Michael Faraday’s discovery of electromagnetic induction was only 12 years in the past. Faraday himself was just 52 years old and still active. In 1845, two years AQ (After Quaternions), Faraday came up with the concept of an electromagnetic field. He saw it all in imaginative terms—“lines of force” and so on—having insufficient grasp of mathematics to make his ideas rigorous. His successors, notably James Clerk Maxwell, filled out the math and found vectors to be exactly what they needed to express these new understandings.

It is hard not to think, in fact, that interest in this wonderful new science of electricity, with currents of all magnitudes flowing in all directions, was one of the major impulses to vectorial thinking at this time.85 Not that physicists found it easy to take vectors on board. There were three schools of thought, right up to the end of the 19th century and beyond.

The first school of vectorial thinking followed Hamilton, who had actually been the first to use the words “vector” and “scalar” in the modern sense. Hamilton regarded a quaternion a + bi + cj + dk as consisting of a scalar part a and a vector part bi + cj + dk and developed a way of handling vectors based on this system, with vectors and scalars rolled up together in quaternionic bundles.

A second school, established in the 1880s by the American Josiah Willard Gibbs and the Englishman Oliver Heaviside, separated out the scalar and vector components of the quaternion, treated them as independent entities, and founded modern vector analysis. The end result was an essentially Grassmannian system, though Gibbs testified that his ideas were already well formed before he picked up Grassmann’s book, and Heaviside seems not to have read Grassmann at all. Gibbs and Heaviside were physicists, not mathematicians, and had the empirical attitude that the more snobbish kinds of pure

mathematicians deplore. They just wanted some algebra that would work for them. If that meant taking a meat cleaver to Hamilton’s quaternions, they had no compunctions about doing so.

A third school, exemplified by the British scientist Lord Kelvin (William Thomson), eschewed all this newfangled math completely and worked entirely in good old Cartesian coordinates x, y, and z. This cheerfully reactionary approach lingered for a long time, at any rate among the English, to whose rugged philistinism it had deep appeal. I learned dynamics in the 1960s from an elderly schoolmaster who was firmly in Lord Kelvin’s camp and declared that vectors were “just a passing fad.”

Disputes over the merits of these systems led to the slightly ludicrous Great Quaternionic War of the 1890s, of which there is a good account in Paul Nahin’s 1988 biography of Oliver Heaviside (Chapter 9). Grassmann, or at any rate Gibbs/Heaviside, was the ultimate victor—the vector victor, if you like. Doing mathematical physics Lord Kelvin’s way, with coordinates, came to seem quaint and cumbersome, while quaternions fell by the wayside.

Thus the algebra of quaternions never fulfilled Hamilton’s great hopes for it, except indirectly. Instead of opening up broad new mathematical landscapes, as Hamilton had believed it would, and as he worked for the last 20 years of his life to ensure it would, the formal theory of quaternions turned out to be a mathematical backwater, of interest in a few esoteric areas of higher algebra but taught to undergraduates only as a brief sidebar to a course on group theory or matrix theory.86

§8.8 The study of n-dimensional spaces went off in other directions in the years AQ. In the early 1850s the Swiss mathematician Ludwig Schläfli worked out the geometry of “polytopes”—that is, “flat”-sided figures, the analogs of two-dimensional polygons and three-dimensional polyhedra—in spaces of four and more dimensions. Schläfli’s papers on these topics, published in French

and English in 1855 and 1858, went even more completely ignored than Grassmann’s Ausdehnungslehre and only became known after Schläfli’s death in 1895. This work properly belongs to geometry, though, not algebra.

Another line of development sprang from Bernhard Riemann’s great “Habilitation” (a sort of second doctorate) lecture of 1854, titled The Hypotheses That Underlie Geometry. Picking up on some ideas Gauss had left lying around, Riemann shifted the entire perspective of the geometry of curves and surfaces, so that instead of seeing, say, a curved two-dimensional surface as being embedded in a flat three-dimensional space, he asked what might be learned about the surface from, so to speak, within it—by a creature unable to leave the surface. This “intrinsic geometry” generalized easily and obviously to any number of dimensions, leading to modern differential geometry, the calculus of tensors, and the general theory of relativity. Again, though, this is not properly an algebraic topic (though I shall return to it in §13.8, when discussing modern algebraic geometry).

§8.9 The theory of abstract vector spaces and algebras (vector spaces in which we are permitted to multiply vectors together in some manner) developed ultimately into the large area gathered today under the heading “Linear Algebra.” Once you start liberating vector multiplication from the rigidities of commutativity and associativity, all sorts of odd things turn up and have to be incorporated into a general theory.

There are some algebras, for example, in which the zero vector has factors! Actually, Hamilton himself had noticed this when he tried to generalize his quaternions so that the coefficients a, b, c, and d in the quaternion a + bi + cj + dk are not just real numbers (as he originally saw them) but complex numbers. Over the field of complex numbers, for instance, I can do this factorization:

(I have written “![]() ” there to avoid confusion with the i of Hamilton’s quaternions, which is not quite the same thing as the i of complex numbers.) If I substitute Hamilton’s j for x, I get

” there to avoid confusion with the i of Hamilton’s quaternions, which is not quite the same thing as the i of complex numbers.) If I substitute Hamilton’s j for x, I get

But by Hamilton’s definition, j2 = −1, so ![]() and

and ![]() are factors of zero. This is not a unique situation in modern algebra. Matrix multiplication, which I shall cover in the next chapter, will often give you a result matrix of zero when you multiply two nonzero matrices. This result does, though, show how quickly the study of abstract algebras slips away from the familiar world of real and complex numbers.

are factors of zero. This is not a unique situation in modern algebra. Matrix multiplication, which I shall cover in the next chapter, will often give you a result matrix of zero when you multiply two nonzero matrices. This result does, though, show how quickly the study of abstract algebras slips away from the familiar world of real and complex numbers.

It is an interesting exercise to enumerate and classify all possible algebras. Your results will depend on what you are willing to allow. The narrowest case is that of commutative, associative, finite-dimensional algebras over (that is, having their scalars taken from) the field of real numbers ![]() and with no divisors of zero. There are just two such algebras:

and with no divisors of zero. There are just two such algebras: ![]() and

and ![]() , a thing proved by Karl Weierstrass in 1864. By successively relaxing rules, allowing different ground fields for your scalars, and permitting things like factors of zero, you can get more and more algebras, with more and more exotic properties. The American mathematician Benjamin Peirce carried out a famous classification along these lines in 1870.

, a thing proved by Karl Weierstrass in 1864. By successively relaxing rules, allowing different ground fields for your scalars, and permitting things like factors of zero, you can get more and more algebras, with more and more exotic properties. The American mathematician Benjamin Peirce carried out a famous classification along these lines in 1870.

A Scottish algebraist, Maclagen Wedderburn, in a famous 1908 paper titled “On Hypercomplex Numbers” took algebras to a further level of generalization, permitting scalars in any field at all … But now I have wandered into topics—fields, matrices—to which I have so far given no coverage. Matrices, in particular, need a chapter to themselves, one that starts out in Old China.