Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra (2006)

Chapter: 11 Pistols at Dawn

Chapter 11

PISTOLS AT DAWN

§11.1 MATHEMATICS IS, LET’S FACE IT, a dry subject, with little in the way of glamour or romance. The story of Évariste Galois has therefore been made much of by historians of math.

A little too much, perhaps. The facts of the Galois story, to the degree that they are known, have been surrounded by a fog of myth, error, speculation, and agenda-peddling. Best known in English is the chapter “Genius and Stupidity” in E. T. Bell’s classic Men of Mathematics, which tells the story of a legion of fools persecuting an ardently idealistic genius who spends his last desperate night on earth committing the foundations of modern group theory to paper. Bell’s story is certainly false in details and probably in the character it draws for Galois. Tom Petsinis’s 1997 novel The French Mathematician, though written in a style not at all to my taste and with an ending that strikes me as improbable, is sounder on the facts of Galois’ case. Best of all for an hour or so of reading is the Web site by cosmologist and amateur math-historian Tony Rothman, which weighs all the sources very judiciously.109

Galois died in a duel at the age of 20 years and 7 months. The duel, fought with pistols, naturally took place at dawn. Galois, apparently sure that he was going to be killed—perhaps even wishing

for it—sat up the night before, writing letters. Some were to political friends, antimonarchist republicans like himself. One, with some annotations to his mathematical work, was to his friend Auguste Chevalier.

The reason for the duel is unclear. It was either political or amorous, possibly both. “I have been provoked by two patriots …,” Galois wrote in one of those letters. In another, however, he says: “I die the victim of an infamous coquette….” Galois had been involved in the extreme-republican politics that flourished in Paris around the time of the 1830 uprising—the uprising portrayed in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. He was also suffering from unrequited love.

Romantic enough, to be sure. As usually happens in these cases, a close look at the circumstances replaces some of the romance with pathos and squalor. Galois’s story is certainly a sad one, though, and the fact that his own awkward personality seems to have played a large part in his misfortunes does little to diminish the sadness.

§11.2 The France of 1830 was not a happy nation. The king, Charles X, of the Bourbon dynasty restored by the allies after the defeat of Napoleon, was old and reactionary. Down at the other end of society, rapid urbanization and industrialization were turning much of Paris into a horrible slum, in which hundreds of thousands dwelt in misery and near-starvation. This was the Paris drawn by Balzac and Victor Hugo, where a thrusting, materialistic bourgeoisie dwelt alongside a seething underclass. The employment prospects of the latter were at the mercy of untamed business cycles; their miseries were alleviated only by occasional charity.

In 1830, there was a recession. Bread prices soared, and more than 60,000 Parisians had no work. In July, barricades went up; the mob took control of the city; Charles X was forced to flee the country. Louis Philippe, the Duke of Orléans, from a distant branch of the Bourbons, was chosen by progressive-bourgeois parliamentary deputies to be the new king—“the July monarch.” Amiable and unpreten-

tious, Louis Philippe was something of a limousine liberal. A radical element was coming up in French politics, however, and they could not be satisfied by any mere liberal. The 1830s were punctuated by insurrections, including a major one in Paris in 1831. These were tense years, when hot-headed young men with strong opinions could reasonably expect to find themselves watched by the police, perhaps to do some brief prison time.

§11.3 Évariste Galois was born in October 1811 in the little town of Bourg-la-Reine, just south of Paris—it is now a suburb—on the road to Orléans. Galois père was a liberal, an anticlericalist and antiroyalist. He had been elected mayor of the town in 1815, during Napoleon’s last days as emperor, the “hundred days” that ended at Waterloo. After the monarchy was restored, this elder Galois took an oath of loyalty to the Bourbons—not from any change of heart but to prevent a real royalist from getting his job.

The first comments we have about Galois’ character come from his Paris schoolmasters. They show a youth who was clever but introverted, not well organized in his work, and not willing to listen to advice. Tony Rothman notes that: “The words ‘singular,’ ‘bizarre,’ ‘original’ and ‘withdrawn’ would appear more and more frequently during the course of Galois’ career at Louis-le-Grand. His own family began to think him strange.” Rothman adds, however, that the opinions of Galois’ teachers were far from unanimous and that his schooldays were by no means the nightmare of uncomprehending persecution described by E. T. Bell.

In July of 1829—Galois was not yet 18—his father, who had been enduring a campaign of slander by a malicious local priest, committed suicide in a Paris apartment just a few yards from Évariste’s school. The event caused Galois intense and lasting distress. Just a few days later he had to attend a viva voce examination for entry to the very prestigious École Polytechnique, whose faculty included Lagrange, Laplace, Fourier, and Cauchy. Galois failed the exam through tact-

lessness, possibly rising to the level of willful arrogance. At one point he responded to a request to prove some mathematical statement by saying that the statement ought to be perfectly obvious. A few months later—we are now in early 1830, Galois was 18 1/2—he was accepted into the less prestigious École Preparatoire, essentially a teacher training college (now called the École Normale).

The first version of Galois’ theory on the solution of equations—the paper that E. T. Bell implies was scribbled out frantically the night before Galois died—had actually been submitted to the Academy of Sciences a few weeks before Galois père killed himself. Cauchy was appointed referee for the paper. Bell (and, to be fair, everyone else, until recent researches in the Academy’s archives turned up exculpatory evidence) believed that Cauchy just lost or ignored the paper. To the contrary, the great man seems to have thought highly of it. It is likely he suggested that Galois polish it a little and submit it for the Academy’s grand prize in mathematics. At any rate, whether at Cauchy’s suggestion or not, Galois did just that, submitting the paper a second time in February 1830 to Joseph Fourier, secretary of the Academy. Alas, Fourier died on May 16.

Cauchy might yet have rescued Galois from obscurity. This was the year of revolution, though, and the new liberal regime of Louis Philippe was hard for Cauchy to stomach. He was in any case a man of strong principles. Having sworn an oath of loyalty to Charles X, he did not feel he could now swear one to Louis Philippe. He might have just resigned his chairs and retired to some private provincial position (he was 40 at this point). Instead, he exiled himself, staying out of France for eight years. There is no good explanation for Cauchy’s self-imposed exile, other than the penchant for “quixotic behavior” noted by Freudenthal (§7.5).

Galois himself did not take part in the July revolution. Knowing that his student body contained a large radical element, the director of the École Preparatoire locked the students in, so that they could not take part in the street fighting. Galois was, though, sufficiently free with his radical opinions to get himself expelled from the college.

That was at the beginning of January 1831. The last 17 months of Galois’ life then proceeded as follows:

January 4, 1831—Expelled from the École Preparatoire. Galois seems to have spent the next four months trying to make a living by teaching mathematics privately in Paris, while hanging out with other young people of extremist republican sympathies.

January 17—Submitted a third version of the memoir on the solution of equations to the Academy. Siméon-Denis Poisson was to be the referee.

May 9—Attended a rowdy republican banquet at which he seemed, when proposing a toast, to have threatened the life of Louis-Philippe. Galois was arrested the next day.

June 15—Tried but acquitted, probably on account of his youth.

July 14 (Bastille Day)—Got arrested again, with his friend Ernest(?) Duchâtelet, for wearing the uniform of the banned Artillery Guard. Also, apparently, for being armed. Galois is reported to have been in possession of a loaded rifle, “several pistols,” and a dagger.

(Galois was imprisoned from July 14, 1831, to April 29, 1832. The conditions of imprisonment do not seem to have been very arduous, though. The prisoners were, for example, frequently drunk.)

October—Received a letter of rejection from Poisson at the Academy. He had found Galois’ paper too difficult to follow, though he was not condemnatory, and suggested an improved presentation.

March 16, 1832—Transferred with other inmates from the prison to a sanatorium, to protect them from the cholera epidemic then sweeping Paris. The sanatorium served as an “open prison,” and Galois had considerable freedom to come and go. Here he fell in love with Stéphanie Dumotel, daughter of one of the resident physicians. His love, however, was not requited.

April 29—Galois freed.

May 14—The date on a rejection letter Galois seems to have received from Stéphanie.

May 25—The date on a letter written by Galois to his friend Auguste Chevalier, telling of a broken love affair.

May 30—The fatal duel.

The precise circumstances of the duel, and indeed of Galois’ last few days of life, are mysterious and will probably always remain so. It is likely that Galois had, in some sense, given up on life. The death of his father, the rejection of his paper (following on the misfortunes of its previous submission), his unrequited love for Stéphanie, his own small-to-nonexistent employment prospects, the months of confinement, the wretchedness of Paris during the epidemic—it was all too much for him.

On June 4, a Lyons newspaper printed a brief report on the duel that makes it appear to be a competition between two old friends for some woman’s favors, settled by a sort of Russian roulette. “The pistol was the chosen weapon of the adversaries, but because of their old friendship they could not bear to look at one another….” The newspaper identified Galois’ adversary only as “L. D.” Presumably the woman was Stéphanie, but who is L. D.? The D could, under the prevailing standards of orthography, stand for either Duchâtelet or Perscheux d’Herbinville, another republican acquaintance of Galois. Neither is known to have had a forename beginning with L, but then neither is known not to have. French parents can be generous with forenames.

Galois’ brother and friends copied out his papers and circulated them to big-name mathematicians of the day, including Gauss, but with no immediate result. At length, 10 years after the fatal duel, the French mathematician Joseph Liouville took an interest in the papers. He announced Galois’ main result to the French Academy in 1843 and published all of Galois’ papers three years later in a math journal he had founded himself.110 Only then did the name of Évariste Galois become known to the larger mathematical community.

§11.4 What was the nature of Galois’ work on the solution of equations that made it so important to the development of algebra? I shall give a brief account here, but I shall use modern language, not the language Galois himself used.

In Figure 10-1, I displayed a Cayley table—that is, a “multiplication” table—for the permutations of three objects. There are six possible permutations, and they can be compounded (first do this one, then do that one) according to the table. After that, in Figure 10-2, I showed another table, the one for multiplication of the sixth roots of unity. I said that these two tables illustrated the two groups having six members—groups of order 6.

Those tables show the essential features of abstract group theory. A group is a collection of objects—permutations, numbers, anything—together with a rule for combining them. The rule is most often represented as multiplication, though this is just a notational convenience. If the objects are not numbers, it can’t be real multiplication.

To qualify as a group, the assemblage (objects plus rule) must obey the following principles or axioms:

Closure. The result of compounding two of the elements must be another one of them—must “stay within the group.”

Associativity. If a, b, and c are any elements of the group and × is the rule for compounding them, then a × (b × c) = (a × b) × c always. With this rule we can unambiguously compound three or more elements of the group.

Existence of a unity. There is some element of the group that, when compounded with any other element, leaves the other element unchanged. If we call this special element 1, then for every element a in the group it is the case that 1 × a = a.

Every element has an inverse. If a is any element of the group, I can find an element b for which b × a = 1. This element is called the inverse of a and is frequently written as a−1.

This highly abstract way of defining a group by means of axioms, using the language of set theory—“elements,” “compounding”—is typical of the 20th-century axiomatic approach I have mentioned. This approach was of course not available to Galois, who expressed his ideas in terms of the particular properties of permutation groups.

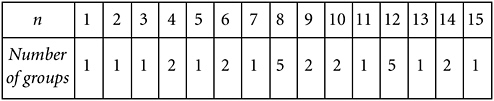

The number of elements in a group is called its order. You can easily check that both those six-member groups in §10.6 satisfy the axioms for a group. What is not so easy to check is that there are no other groups of order 6. I mean abstract groups, of course—there are many other instances of six things that behave groupily (I shall produce one in a moment), but their rules of combination all follow the pattern in one or another of the Cayley tables of §10.6. Those multiplication tables offer the only two possible patterns for groups of six elements. There are no others. That is, there are only two abstract groups of order 6, though each one has numerous illustrating instances. Cayley, in his 1854 papers, listed all the groups of order up to 6. Nowadays we of course know far more groups. Figure 11-1 shows the number of abstract groups of order n, for n from 1 to 15.

How can we find the number of groups for any given order n? There is no general method and no formula. There are, however, some things to be noticed. If n is a prime number, for example, there seems never to be more than one group of order n. That is correct. For any prime number p, the only group of order p is Cp, the group illustrated by the pth roots of unity with ordinary multiplication and known technically as the cyclic group of order p.

FIGURE 11-1 The number of groups of order n, for n from 1 to 15.

Here are the two groups of order 4. Both were found by Cayley. I am just going to use arbitrary symbols α, β, and γ for their elements (other than the unity, which I shall write as 1).

FIGURE 11-2 The two abstract groups of order 4, C4 and C2 × C2.

These two groups both have names. The one on the left is named C4. It is the cyclic group of order 4, illustrated by the fourth roots of unity, as you can see by setting α, β, γ equal to i, −1, and −i, respectively. The one on the right is named C2 × C2, or the Klein 4-group. Both are commutative.111

Looking at that left-hand group C4, if I tell you that the groups of order 3, 5, and 7 are named C3, C5, and C7, respectively, you should be able to write out their multiplication tables very easily. The only group of order 2 is the one in my Figure FT-3. The order-1 group is of course trivial, included only for completeness. So now you know all the groups of order up to 7, which puts you slightly ahead of Arthur Cayley.

§11.5 Galois’ great insight concerned the structure of abstract groups. Look at that group on the right in Figure 11-2, the Klein 4-group. The two elements 1 and α form a little group within the group—a subgroup, of order 2. So, for that matter, do 1 and β or 1 and γ. If you now look at the left-hand group in Figure 11-2, though, the one I introduced as C4, you will see that 1 and β form a

little group within a group, but 1 and α or 1 and γ do not. This is what I mean by structure. These groups-within-groups, these subgroups, play a key role in group theory.

Look back to that multiplication table for the group S3, the group of permutations on three objects, in Figure 10-1. A number of subgroups are present. There is a subgroup of order 3, consisting of I, (123), and (132) (all the even permutations, please note). Then there are three subgroups of order 2: the one consisting of I and (23), the one consisting of I and (13), and the one consisting of I and (12). Each of these four subgroups forms its own happy little self-contained unit. Within it you can multiply as much as you like, take inverses as often as you like, and you will never be dragged outside the subgroup. In the second order-6 subgroup (Figure 10-2), the one named C6, there is one subgroup of order 3, consisting of the cube roots of unity (1, ω, and ω2), and there is one subgroup of order 2, consisting of the square roots of unity (1 and −1).

The first great theorem about group structure was Lagrange’s theorem, which I mentioned in §7.4: The order of a subgroup divides the order of a group exactly. The quotient of this division is called the index of the subgroup. Lagrange’s theorem forbids a fractional index. We may find subgroups of order 2 or 3 (index 3 or 2, respectively) in a group of order 6, but we can be sure we shall never find a subgroup of order 4 or 5 because neither 4 nor 5 divides into 6.

Galois added a key concept to the notion of group structure, the concept of what we nowadays call a normal subgroup. Here is a very brief account, using for illustration the group S3, and the subgroup made up of I and (12), which I’ll call H, and which is, of course, an instance of the one and only abstract group of order 2, shown in Figure FT-3.

Pick an element of the main group—one either inside or outside the subgroup; it doesn’t matter. I’ll use (123). Multiply I and (12) in turn by this element. Do the multiplication “from the left,” applying first (123) and then the other permutation, as in §10.6. Result: a set—not a subgroup, just a set—consisting of (123) and (23). This is called

a “left coset” of H. Repeat what you just did with (123), using every other element of the main group S3. This gives you an entire family of left cosets. There is the one I just showed, {(123), (23)}. (Note: Those curly brackets are the usual way to denote a set. The set consisting of London, Paris, and Rome is written mathematically as {London, Paris, Rome}.) Then there is this one: {(132), (13)}. And there is this one: {I, (12)}, which is just H itself. (Since S3 has order 6, you might have expected six members in the left-coset family, but they turn out to be equal in pairs.)

Repeat the entire process, but this time multiply “from the right.” This gives you a family of “right cosets”: {(123), (13)}, {(132), (23)}, and {I, (12)}. Now, if the family of left cosets is identical to the family of right cosets, then H is a normal subgroup. In my example the two families are not identical, so this particular H is not a normal subgroup of S3. It’s just a plain-vanilla subgroup. However, the order-3 subgroup of S3, the one consisting of all the even permutations, is a normal subgroup. I leave you to check that. And notice one thing that follows from this definition: If a group is commutative, then every subgroup is normal.

Galois showed that to any polynomial equation of degree n in one unknown

we can, by studying the relationship between the field of coefficients and the field of solutions (see §FT.8), associate a group. If this “Galois group” of the equation has a structure that satisfies certain conditions, in which the concept of a normal subgroup is of central importance, then we can express the equation’s solutions using only addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and extraction of roots. If it doesn’t, we can’t. If n is less than 5, the equation’s Galois group will always have the appropriate structure. If n is 5 or more, it may or may not have, depending on the actual numerical values of p, q, and the other coefficients. Galois uncovered those group-structural conditions, thereby supplying a definitive, final answer to the question:

When is it possible to find algebraic formulas for the solutions of polynomial equations?

§11.6 Although Galois’ work marked the end of the equation story, it also marked the beginning of the group story. That is how I am treating Galois theory in this book: as a beginning, not an end.

I left the historical thread at the end of §11.3 with Liouville’s publication of Galois’ papers in 1846. Then, as now, Galois’ theory could be taken either as an end or a beginning. Those mathematicians who took notice of Galois’ work seem mainly to have adopted the “end” view. A family of problems dating back for centuries, concerning the solution of polynomial equations, has been wrapped up once and for all. Good! Now let’s press forward with the new, promising areas of mathematics: function theory, non-Euclidean geometry, quaternions….

The first really significant turn toward the future was taken by a mathematician who came, as Abel had, from Norway. This was Ludwig Sylow (pronounced SÜ-lov), who was born in Oslo, still named Christiania at that time, in 1832, the year of Galois’ death.

The supply of Norwegian mathematicians being greater than the local demand, Sylow spent most of his working life as a high school teacher in the town of Halden, then called Frederikshald, 50 miles south of Oslo. He did not get a university appointment until he was well into his 60s. All through the years of schoolteaching, though, he kept up his mathematical studies and correspondence.

Sylow was naturally drawn to the work of his fellow countryman Abel on the solvability of equations. Then—this would be in the late 1850s—one of the professors at the University of Christiana showed him Galois’ paper, and Sylow began to investigate permutation groups. Bear in mind that abstract group theory, despite Cayley’s 1854 paper, was not yet part of the outlook of mathematicians. Group theory was still a theory of permutations, with the only fruitful application being research into the solutions of algebraic equations.

In 1861, Sylow obtained a government scholarship for a year of travel in Europe. He visited Paris and Berlin, attending lectures by several mathematical luminaries of the time, including that Liouville who had resurrected and published Galois’ papers 15 years before. On his return to Oslo he gave a course of lectures at the university on permutation groups. This was one of the rare lectures on group theory before the 1870s112 and is interesting for another reason I shall mention in §13.7.

Sylow’s inquiries concerned the structure of permutation groups. I have already mentioned Lagrange’s theorem, which imposes a necessary condition for H to be a subgroup of G: The order of H must divide the order of G exactly. Thus a group of order 6 may have subgroups of order 2 and 3, but it may not have subgroups of order 4 or 5.

Sylow’s work centers on that word “may.” All right, a group of order 6 may have subgroups of order 2 and 3. But does it? Can we get some better rules than Lagrange’s simple necessary-but-not-sufficient division test for subgroups? Cauchy had already shown that if the order of a group has prime factor p, there is a subgroup of order p. Can this result be improved on?

It certainly can. In a paper published in 1872, Sylow presented three theorems on this topic, still taught to algebra students today as fundamental results in group theory. I shall state only the first here.

Sylow’s First Theorem. Suppose G is a group of order n, p is a prime factor of n, and pk is the highest power of p that divides n exactly. [Example: n = 24, p = 2, k = 3.] Then G has a subgroup of order pk.

A subgroup of this kind, with order pk, is called a Sylow p-subgroup of G. And it is infallibly the case, at any point in time, that somewhere in the world is a university math department with a rock band calling themselves “Sylow and his p-subgroup.”

§11.7 The theory of finite groups has subsequently had a long and fascinating history in its own right. It has also found applications in numerous practical fields from market research to cosmology. An entire taxonomy of groups has been developed, with groups of different orders organized into families.

The two groups whose multiplication tables I showed in §10.6 illustrate two of those families. The first was S3, the group illustrated by all possible permutations of three objects, which has order 6. The other was C6, the group illustrated by the sixth roots of unity, also of order 6. Both are members of families of groups. The set of all possible permutations of n objects, with the ordinary method for compounding permutations, illustrates the group Sn, the symmetric group of order n! (that is, factorial n). The nth roots of unity, with ordinary multiplication, illustrate Cn, the cyclic group of order n. We have in fact already spotted a third important family of groups: If you extract from Sn the normal subgroup of even permutations, that is called the alternating group of order n!—to say it more simply, “of index 2”—and always denoted by An.

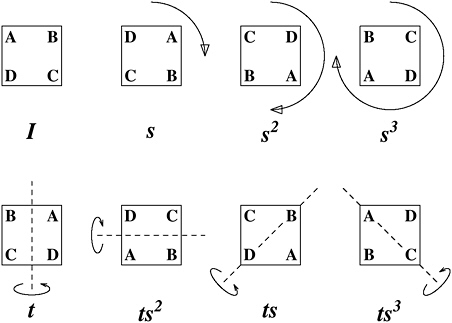

Another important family is the dihedral groups. “Dihedral” means “two-faced,” in the geometric not the personal sense. Cut a perfectly square shape from a piece of stiff card. The shape has two sides—it is dihedral. Label the four corners A, B, C, and D, going in order like that. Lay the square down on a sheet of paper and pencil around its outline, to make a square on the paper. Now ask the question: In how many basic, elementary ways, to which all other ways are equivalent (as a rotation through 720 degrees is equivalent to one through 360 degrees), can I move this square so that it always ends up securely and precisely in its outline?

The answer is 8, and I have sketched them in Figure 11-3, showing the effect of each one on a certain starting configuration, represented by the do-nothing identity movement I. There is that identity; there is clockwise rotation through 90, 180, or 270 degrees; and there are four ways to flip the card over, depending on the axis of

the flip (north-south, east-west, northeast-southwest, or northwest-southeast—these are the four axes of symmetry of the square).

These movements (“transformations” to a mathematician) form a group under the following rule of combination: Apply first one basic movement, then another. Plainly the group has order 8. Its name is D4, the dihedral group of the square. You might want to try writing up a Cayley table for this group. There is a similar group corresponding to any regular n-sided polygon. That group is called Dn. The case n = 2, where the “polygon” is just a line segment AB, has only two members, but for every n from 3 onward, Dn has 2n members. So here is another family of groups.

FIGURE 11-3 The eight elements of the dihedral group D4.

(Note that I have been a little sophisticated with my notation in labeling the members of D4. Once I have defined the 90-degree rotation as s, for example, and the compounding rule as “do this one, then do that one,” the 180-degree rotation is just s2—do an s, then do an-

other s—and the 270-degree one is s3 Similarly, I only need define the flip with a north-south axis as t. The one with a northeast-southwest axis is then ts, and so on. When you can use a smallish number of basic elements, like my s and t, to build up a group, those elements are called generators of the group. What are the generators of the order-4 groups in Figure 11-2?)

Suppose I did that exercise with a triangle, to get D3. Wouldn’t D3 have six members? And haven’t I already said that there are only two abstract groups of order 6, S3 and C6? The answer to this little conundrum is that D3 is an instance113 of S3. If you think about permutations for a moment, you will see why this is so for a triangle but not for a square, nor for any other regular polygon with more than three sides. Any permutation of A, B, and C corresponds to a dihedral motion in D3. This is not so with A, B, C, and D. Permutation (AC) corresponds to the motion ts, but permutation (AB) does not correspond to any motion in D4 (which, by the way, like S3, has both normal and plain-vanilla subgroups—you might try identifying them).

I have already mentioned that if p is a prime number, the only group of order p is the cyclic group Cp, modeled by the p-th roots of unity. Well, if p is a prime number greater than 2, there are only two groups of order 2p. One of them is C2p, the other is Dp.

Looking back to Figure 11-1, which shows the number of groups of each order, you can now very nearly take your understanding up to n = 11. The fly in the ointment is n = 8, for which there are five different groups. Three of them are cyclic, or built up from cyclic, groups: C8, C4 × C2, and C2 × C2 × C2. Another one is of course D4. The fifth is an oddity, the quaternion group, which has the very peculiar property that even though it is not commutative, all its subgroups are normal.

§11.8 I hope by this point you can see the fascination of classifying groups. Perhaps the most historically interesting region of this field of inquiry has been the attempt to classify all simple finite groups. A

simple group is a group with no normal subgroups. Cp, for prime p, has no proper subgroups at all and so is simple by default. An, the group of even permutations of n objects, is simple when n is 5 or more—that, fundamentally, is why the general quintic equation has no algebraic solution. As well as five other families of simple groups, there are 26 “oddities”—one-off simple groups that don’t fit into any family. The biggest one of these “oddities” has order

The classification of all simple finite groups was accomplished in the middle and later 20th century, being finished in 1980. It was one of the great achievements of modern algebra.114