Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra (2006)

Chapter: 13 Geometry Makes a Comeback

Chapter 13

GEOMETRY MAKES A COMEBACK

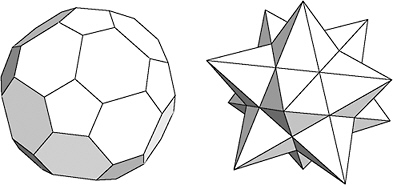

§13.1 TUCKED AWAY IN SOME glass-fronted cabinet in any university math department, anywhere in the world, is a collection of mathematical models. It usually includes several polyhedra, both convex and stellated (see Figure 13-1), some ruled surfaces done with string, glued-together ping-pong balls illustrating the different methods of sphere packing, a Möbius strip, perhaps a Klein bottle, and other oddities.

FIGURE 13-1 Polyhedra, convex (left) and stellated (right).

These models are a little faded and dusty nowadays. With the advent of math-graphics software packages such as Maple and Mathematica, which can generate these figures on one’s computer screen in a trice, and rotate them for inspection, and transform, deform, and intersect them as desired, it seems absurdly laborious to construct them from wood, card, paper, and string. Making physical models of geometric figures was, though, a favorite pastime for mathematicians and math students through most of the 19th and 20th centuries, and I regret that it seems no longer to be done. I myself spent many happy and instructive hours at it in my adolescence, practically wearing out a copy of H. Martyn Cundy and A. P. Rollett’s 1951 classic Mathematical Models. My pride and joy was a card model of five cubes inscribed in a dodecahedron, each cube painted a different color.

This interest in visual aids and models for mathematical ideas is one offspring of the rebirth of geometry in the early 19th century. As I mentioned in §10.1, geometry, despite some interesting advances in the 17th century, was overshadowed from the later part of that century onward by the exciting new ideas brought in with calculus. By 1800, geometry was simply not a sexy area of math, and you could be a respectable professional mathematician at that time without ever having studied any geometry beyond the Euclid you would inevitably have covered in school. A generation later this had all changed.

§13.2 The first advance in the 19th-century geometric revolution was made by a Frenchman, Jean-Victor Poncelet, under very trying circumstances. Poncelet, at the age of 24, set off as an officer of engineers with Napoleon’s army into Russia. He got to Moscow with the conqueror. In the terrible winter retreat that followed, he was left for dead after the battle of Krasnoy (November 16–17, 1812). Spotting his officer’s uniform, a Russian search party carried him off from the battlefield for questioning. Then, a prisoner of war, Poncelet had to walk for five months across the frozen steppe to a prison camp at Saratov on the Volga.

To distract himself from the rigors of imprisonment, Poncelet kept his mind busy by going over the excellent mathematical education he had received at the École Polytechnique. By the time he was allowed to return to France, in September 1814, he had, he tells us, seven manuscript notebooks full of mathematical jottings. These jottings formed the basis for a book, Treatise on the Projective Properties of Figures, the foundation text of modern projective geometry.

Poncelet’s book was not very algebraic. As a matter of fact, it stood on one side of an argument that was conducted quite passionately through the first half of the 19th century, though it seems quaint now: the argument between analytic and synthetic geometers. Analytic geometry, descended from Descartes, uses the full power of algebra and the calculus to discover results about geometric figures—systems of straight lines, conics, more complicated curves and surfaces. Synthetic geometry, descended from the Greeks via Pascal, preferred purely logical demonstrations, with as few numbers and as little algebra as possible.

Since its theorems do not mention distances or angles, projective geometry at first looked like a renaissance of the synthetic approach after two centuries of dull Cartesian number crunching. This proved to be a false dawn. Later in the 1820s, German mathematicians—August Möbius, Karl Feuerbach, and Julius Plücker, working independently—brought in homogeneous coordinates, as described in my primer, allowing projective geometry to be thoroughly algebraized.

In addition to Poncelet’s founding of modern projective geometry, there was another geometric revolution in the 1820s, for it was in 1829 that Nikolai Lobachevsky published his paper on non-Euclidean geometry in a provincial Russian journal. He then submitted it to the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, but they rejected it as being too outrageous. Lobachevsky had argued that the common assumptions of classical geometry—for example, that the three angles in a triangle add up to 180 degrees—might be taken not as universal truths about the world but as optional axioms. By choosing

different axioms, you might be able to get a different geometry, one that didn’t look like Euclid’s at all—a non-Euclidean geometry.

The young Hungarian mathematician János Bolyai had been working along the same lines. So had Gauss, who in 1824 wrote to a friend: “The assumption that the sum of the three angles of a triangle is less than 180 [degrees] leads to a curious geometry, quite different from ours but thoroughly consistent….” Gauss had in fact been mulling over these ideas for some years. He was, however, a man who cherished the quiet life and avoided controversy, so he never published his thoughts.

Controversial those thoughts were, as Lobachevsky’s experience showed. The flat plane (and “flat” space, in its three-dimensional form) geometry of Euclid, with its parallel lines and planes that never meet, its triangles whose angles invariably add up to two right angles, its subtle demonstrations of similarity and congruence, was at this point firmly imbedded in European consciousness. It had been further reinforced by the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, dominant at that time among thinking Europeans. In his 1781 Critique of Pure Reason, Kant had argued that Euclidean geometry is (to express it in modern terms) “hard-wired” into the human psyche. We perceive the universe to be Euclidean, Kant argued, because we cannot perceive it otherwise. In that sense, according to Kant, the universe is Euclidean, and Euclidean truths lie beyond the scope of logical analysis.133

Under these circumstances, the strange new geometries forcing themselves into the consciousness of mathematicians in the 1820s and 1830s were revolutionary—were indeed regarded by good Kantians as subversive. People took their philosophy seriously in those days, when memory of the horrors of the French Revolution and wars were still fresh. What was metaphysically subversive, they thought, might encourage what was socially subversive. If the projective geometry of Poncelet was the first revolution in 19th-century geometry, then the non-Euclidean geometries of Lobachevsky and Bolyai were the second. A third, a fourth, and a fifth were to follow, as we shall see.

§13.3 In the primer preceding this chapter, I mentioned Julius Plücker and his line geometry. Born in 1801—he was a year older than Abel—Plücker had a long career, 43 years (1825–1868) as a university teacher, most of it as a professor at the University of Bonn. His two-volume Analytic-Geometric Developments (1828, 1831) was a state-of-the-art account of algebraic geometry in that time, though mostly done with old-fashioned nonhomogeneous coordinates. In the 1830s he worked on higher plane curves, the word “higher” in this context meaning “algebraic, of degree higher than 2”—to put it another way, algebraic curves more difficult than conics.

This work on plane curves was all done from an “analytical” point of view—that is, employing all the resources of algebra, as it existed in the 1830s, and calculus, to deduce laws governing these curves and their properties. Plücker’s 1839 book Theory of Algebraic Curves dealt definitively with the asymptotes of these curves—that is, with the behavior of the curves near infinity.

Plücker’s line geometry came much later, after a 17-year interval (1847–1865) in which he took up physics, occupying the Bonn University chair in that subject. The work on line geometry was in fact unfinished when he died in 1868, and it was left to his young research assistant, Felix Klein, to finish it. I shall have much more to say about Klein a little later.

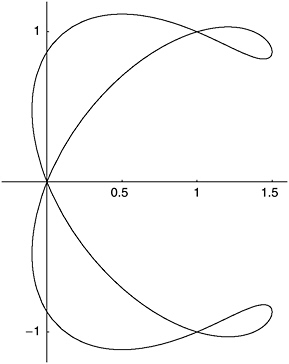

This interest in curves was a great mathematical growth point in the middle 19th century, nourished by algebra and calculus as well as by geometry. It is an easy interest to acquire, or rather it was in the days before math software came up, the days when you had to work hard, using a lot of computation and a lot of insight, to turn an algebraic equation into a curve on a sheet of graph paper. Who knew, for example, that this rather pedestrian algebraic equation of the fourth degree,

represents, when you plot y against x, the lovely ampersand shape shown in Figure 13-2? Well, I knew, having plotted that curve with

FIGURE 13-2 Ampersand curve.

pencil, graph paper, and slide rule during my youthful obsession with Cundy and Rollett’s Mathematical Models, which gives full coverage to plane curves as well as three-dimensional figures.

The reader who at this point might be beginning to suspect that the author’s adolescence was a social failure would not be very seriously mistaken. In partial defense of my younger self, though, I should like to say that the now-lost practices of careful numerical calculation and graphical plotting offer—offered—peculiar and intense satisfactions. This is not just my opinion, either; it was shared by no less a figure than Carl Friedrich Gauss. Professor Harold Edwards makes this point very well, and quotes Gauss on it, in Section 4.2 of his book Fermat’s Last Theorem. Professor Edwards:

Kummer, like all other great mathematicians, was an avid computer, and he was led to his discoveries not by abstract reflection but by

the accumulated experience of dealing with many specific computational examples. The practice of computation is in rather low repute today, and the idea that computation can be fun is rarely spoken aloud. Yet Gauss once said that he thought it was superfluous to publish a complete table of the classification of binary quadratic forms “because (1) anyone, after a little practice, can easily, without much expenditure of time, compute for himself a table of any particular determinant, if he should happen to want it … (2) because the work has a certain charm of its own, so that it is a real pleasure to spend a quarter of an hour in doing it for one’s self, and the more so, because (3) it is very seldom that there is any occasion to do it.” One could also point to instances of Newton and Riemann doing long computations just for the fun of it…. [A]nyone who takes the time to do the computations [in this chapter of Professor Edwards’s book] should find that they and the theory which Kummer drew from them are well within his grasp and he may even, though he need not admit it aloud, find the process enjoyable.

I note, by the way, that according to the DSB, Julius Plücker was a keen maker of mathematical models.

Cundy and Rollett did not pluck my Figure 13-2 out of thin air. They got it from a little gem of a book titled Curve Tracing, by Percival Frost. I know nothing about Frost other than that he was born in 1817 and became a fellow of King’s College, Cambridge, and also of the Royal Society. His book, first published in 1872, shows the reader every conceivable method, including some ingenious shortcuts, for getting from a mathematical expression—Frost does not restrict himself to algebraic expressions—to a plane graph. My own copy of Curve Tracing, a fifth edition from 1960, includes a neat little booklet pasted to the inside back cover, containing pictures of all the scores of curves described in the text. The ampersoid curve of my Figure 13-2 is Frost’s Plate VII, Figure 27.

Frost’s book in turn looks back to the midcentury algebraic geometers, of whom Plücker was one of the earliest of the big names. Along the same lines (so to speak) as Frost’s Curve Tracing, but math-

ematically far deeper, are Irish mathematician George Salmon’s four textbooks: A Treatise on Conic Sections (1848), A Treatise on Higher Plane Curves (1852), Lessons Introductory to the Modern Higher Algebra (1859), and A Treatise on the Analytic Geometry of Three Dimensions (1862). I have a copy of Higher Plane Curves on my desk. It is full of wonderful jargon, mostly extinct now, I am very sorry to say: cissoids, conchoids, and epitrochoids; limaçons and lemniscates; keratoid and ramphoid cusps; acnodes, spinodes, and crunodes; Cayleyans, Hessians, and Steinerians.134 Homogeneous coordinates had “settled in” by Salmon’s time, though he calls them “trilinear” coordinates.135

§13.4 Salmon was another “avid computer.” In the second edition of his Higher Algebra he included an invariant he had worked out for a general curve of the sixth degree. If you look at the invariants for the general conic I gave in my primer, you will believe that this was no mean feat. In fact, it fills 13 pages of Salmon’s book.

I mention this as a useful reminder that this midcentury fascination with curves and surfaces was being fed in part from pure algebra and was feeding some results back in turn. The invariants I described in my primer were first conceived in entirely algebraic terms; the geometrical interpretations were secondary.

Arthur Cayley (a close friend of Salmon’s, by the way) and J. J. Sylvester were key names in this field from the 1840s on. Most of their work concerned invariants of polynomials, not unlike the ones I illustrated in my primer for the degree-2 polynomial in x and y (or x, y, and z, if we use homogeneous coordinates) that represent a conic. Now, the set of all polynomials in, say, three unknowns x, y, z, with coefficients taken from some field, say the field ![]() of complex numbers, forms a ring under ordinary addition and multiplication. You can add two polynomials, or subtract them, or multiply them:

of complex numbers, forms a ring under ordinary addition and multiplication. You can add two polynomials, or subtract them, or multiply them:

However, you can’t reliably divide them. It’s a ring. The study of invariants in polynomials is therefore really just a study of the structure of rings.

Nobody thought like that in the 19th century. The first glimpses of the larger river—theory of rings—into which the smaller one—theory of invariants—was going to flow, came in the late 1880s, with the work of Paul Gordan and David Hilbert.

Both these men were German, though Gordan was the older by a generation. Born in 1837, from 1874 on he was a professor at Erlangen University, a colleague of Emmy Noether’s father. Emmy was in fact Gordan’s doctoral student. She is said to have been his only doctoral student, for his style of mathematics—he had studied at Berlin—was highly formal and logical, with much lengthy computation, Roman rather than Greek. By the 1880s, Gordan was the world’s leading expert on invariant theory. He had not, however, been able to prove the one key theorem that would have tied up the theory into a neat package. He could prove it in certain special cases but not in all generality.

Enter David Hilbert. Born in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia) in 1862, Hilbert became a Privatdozent at that city’s university in 1886. Visiting Erlangen in 1888, he met Gordan, and his attention was snagged by that outstanding problem of invariant theory—Gordan’s problem, it was called, since Gordan pretty much owned the theory. Hilbert mulled over it for a few months—then solved it!

Hilbert published his proof in December of that year and promptly sent a copy to Cayley at Cambridge. “I think you have found the solution of a great problem,” wrote Cayley (who was 68 years old at this point). Gordan was much less enthusiastic. Though Hilbert had not yet held any position at Göttingen, his proof was “very Göttingen” in style: brief, elegant, abstract, and intuitive—Greek, not Roman. This did not suit Gordan’s Berlin sensibility. Sniffed he: Das is nicht Mathematik, das ist Theologie. (“That’s not math, that’s theology.”) Felix Klein, who was at Göttingen, having taken up a professor-

ship there in 1886, was so impressed with the proof that he decided there and then to get Hilbert on his staff as soon as possible.

§13.5 Rather than attempt to describe that proof,136 I am going to dwell for a moment on Hilbert’s slightly later, less sensational, but more accessible result: the Nullstellensatz (“Zero Points Theorem,” but always referred to by its German name). The Nullstellensatz introduces the concept of a variety and offers an easy connection with geometry.

That connection is an odd one, historically speaking, since Hilbert developed the Nullstellensatz in the context of algebraic number theory, not algebraic geometry. It is a theorem about the structure of commutative rings and properly belongs in ring theory. The algebraic geometers have got their hands on it very firmly by now, though. Open any textbook on algebraic geometry137 and you will find the Nullstellensatz in the first two or three chapters. I am therefore not going to feel too guilty about offering a geometric interpretation, but I ask the reader to keep in mind that this is really a theorem in pure algebra, in ring theory.

Well, what does it say, this Nullstellensatz? Consider the ring of all polynomials in three unknowns x, y, and z. Just pause to remind yourself that this is indeed a ring: addition, subtraction, and multiplication all work; division works only sometimes. Remind yourself, too, that setting one of those polynomials equal to zero defines some region—usually a curved surface—of three-dimensional space. (I am using ordinary Cartesian coordinates here, not homogeneous ones.) The polynomial x2 + y2 + z2 − 8, for example, is equal to zero when (x,y,z) are the coordinates of some point on the surface of a sphere centered on the origin, radius ![]() . Associate that polynomial, in your imagination, with the surface of that sphere.

. Associate that polynomial, in your imagination, with the surface of that sphere.

Now let’s consider an ideal in that polynomial ring. An ideal, just to remind you, is a subring, a ring within the ring, having this one

extra property: If you multiply any element of the subring by any element of the parent ring, the result is still in the subring.

Consider, for example, all polynomials that look like this: Ax2 + Bxy + Cy2, where A, B, and C are any polynomials at all in x, y, and z (including the zero polynomial). This is an ideal within the larger ring of all x, y, z polynomials. The polynomial (x + y + z)(x2 + y2) is in the ideal; the polynomial x3 + y3 + z3 is not.

Now I am going to introduce the key concept of a variety, more properly an algebraic variety. Geometrically speaking, this is just a generalization of the notion of a curve in two dimensions, or of a surface or “twisted curve” in three dimensions. In fact, a variety is the set of zero points of some polynomial, or some family of polynomials.138

So the sphere-surface I mentioned above, the points in space at which the polynomial x2 + y2 + z2 − 8 is equal to zero, is a variety. So is the intersection of that sphere with the circular cylinder whose equation is x2 + y2 − 4 = 0. (See Figure 13-3.) That intersection consists of the perimeters of two horizontal circles of radius 2 in three-dimensional space, one at height 2 above the xy coordinate plane, the other at 2 below it. These circles are the variety, the zero-point set, of the polynomial pair x2 + y2 + z2 − 8 and x2 + y2 − 4.

FIGURE 13-3 Two polynomials meet (left) to create a variety (right).

Now, that ideal I described a moment ago is a set of polynomials. It therefore defines a variety—all the points for which every polynomial in the ideal works out to zero. What, actually, is that variety, that zero point set? For which set of points do all those polynomials in the ideal work out to zero? The answer is the z-axis. The variety defined by that ideal is just that single straight line you get when x = 0, y = 0, and z can be anything you like.

Here is what Hilbert’s Nullstellensatz says: If a polynomial equals zero on every point of that variety—in this case, every point of the z-axis—then some power of that polynomial is in the ideal. The polynomial 7x − 3y, for example, is zero on every point of the z-axis. It is not in the ideal but its square is: 49x2 − 42xy + 9y2.

I have, of course, oversimplified dramatically there. There need not just be three unknowns x, y, and z; there might be any number. The variety of my example is a particularly simple one … and so on. Perhaps the worst of my sins of oversimplification has been the assumption (I didn’t say it, but left it “understood”) that the coefficients of the x, y, z polynomials making up my ring are real numbers. In fact, they need to be complex numbers—the Nullstellensatz is not generally true for polynomials with real-number coefficients.139

In this respect the Nullstellensatz resembles the fundamental theorem of algebra. The two theorems are in fact connected at a deep level, and the Nullstellensatz is sometimes called the fundamental theorem of algebraic geometry. The connection is better expressed by the so-called weak form of the Nullstellensatz: The variety corresponding to some ideal in a polynomial ring won’t be empty (unless the ideal is the whole ring). The polynomials making up an ideal are bound to have some common zero points—hence the name of the theorem. Compare the FTA, which says that the zero set of a polynomial in one unknown will, likewise, not be empty.

§13.6 Hilbert’s statement of the Nullstellensatz came in 1893. That was three further revolutions in geometry on from the midpoint of

the century. Only the last, the fifth, of these revolutions was algebraically inspired, though revolutions three and four had profound effects on algebra in the 20th century.

Those third and fourth revolutions were both initiated by Bernhard Riemann, perhaps the most imaginative mathematician that ever lived. (His dates were 1826–1866.)

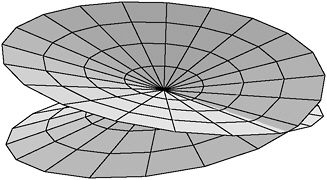

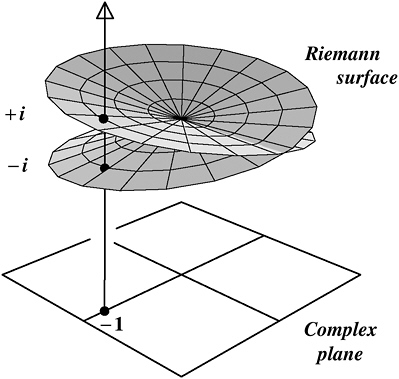

In his doctoral thesis at Göttingen in 1851, Riemann presented his Riemann surfaces, self-intersecting curved sheets that can be used as replacements for the ordinary complex plane when investigating certain kinds of functions.

Riemann surfaces arise when we regard a function as acting on the complex plane. The complex number −2i, for example, lives on the negative imaginary axis, south of zero. If you square it, you get −4, which lives on the negative real axis west of zero. You can imagine the squaring function having winched −2i around counterclockwise through 270 degrees to get it to its square at −4.

Bernhard Riemann thought of the squaring function like this. Take the entire complex plane. Make a straight-line cut from the zero point out to infinity. Grab the top half of that cut and pull it around counter-clockwise, using the zero point as a hinge. Stretch it right around through 360 degrees. Now it’s over the stretched sheet, with the other side of the cut under the sheet. Pass it through the sheet (you have to imagine that the complex plane is not only infinitely stretchable but also is made of a sort of misty substance that can pass through itself) and rejoin the original cut. Your mental picture now looks something like Figure 13-4. That is a sort of picture of the squaring function acting on ![]() .

.

The power of Riemann surfaces really applies when you look at them from the inverse point of view. Inverse functions are a bit of a nuisance mathematically. Take the square root function, which is the inverse of the squaring function. The problem with it is that any nonzero number has two square roots. Square root of 4? Answer: 2 … or −2. Both 2 and −2 give result 4 when you square them. There is no

FIGURE 13-4 A Riemann surface corresponding to the squaring function.

getting around this, but Riemann surfaces offer a more sophisticated way to cope with it.140

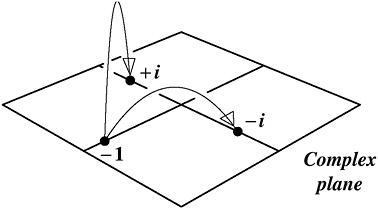

Consider, for example, the fact that the square root of −1 is i … or −i. Pre-Riemann, a mathematician would have visualized that statement using some image like Figure 13-5.

The Riemann surface shown in Figure 13-4, however, has all the complex numbers stacked up in pairs, one on top of the other (except along the “crease”—but the position of the crease is arbitrary, and if I had available to me the four dimensions I really need for drawing this diagram, I could make it disappear).

FIGURE 13-5 The number −1 has two square roots (the pre-Riemann view).

This suggests Figure 13-6 as an alternative way to contemplate the square root function. The Riemann surface that I developed by thinking about the squaring function turns out to be an excellent way to illustrate the inverse of that function—the square root function. The number −1 has two square roots, and there they are, on a single line piercing the Riemann surface in two points.

The importance of this first Riemann revolution is that it threw a bridge between the theory of functions, which belongs to the mathematical topic called analysis, and topology—a branch of geometry that had barely gotten off the ground when Riemann came up with all this!

I shall say more about topology in my next chapter. Here I shall only note that the analysis-topology bridge that Riemann created

FIGURE 13-6 The number −1 has two square roots (the post-Riemann view).

opened up function theory to attack by all the sophisticated tools of algebraic geometry and algebraic topology that developed during the 20th century. One of the central theorems here, the Riemann–Roch theorem,141 relates the analytic properties of a function to the topological properties of the corresponding Riemann surface. In a joint paper published in 1882, Richard Dedekind and Heinrich Weber found a purely algebraic proof of Riemann–Roch, by applying the theory of ideals to Riemann surfaces. That was the result I mentioned in §12.6.

(It may very well be the case, in fact, that Riemann–Roch, in ever more generalized forms, has provided mathematicians of the past 140 years with more work than any other single theorem.)

Not content with having started one revolution in geometry, in 1854 Riemann fired off revolution number four with his stunning habilitation thesis, “On the Hypotheses That Lie at the Foundations of Geometry.” Here Riemann created all of modern differential geometry, laying out the mathematics that Albert Einstein would pick up, 60 years later, to use as the framework for his general theory of relativity.

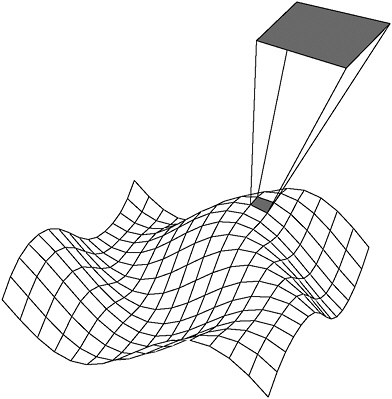

As with Riemann surfaces, the algebraic consequences were indirect. Riemann’s thesis provides the primary source for the key 20th-century concept of a manifold—a space, of any number of dimensions, that is “locally flat,” that is, that can be treated as an ordinary Euclidean space as a first approximation at small scales, just as we regard the curved surface of the Earth as flat for most everyday purposes (see Figure 13-7). This became a key concept in 20th-century algebraic geometry. (The word “manifold”—Mannigfaltigkeit in his German—was in fact coined by Riemann, though not in this paper.)

The fifth geometric revolution of the 19th century was the most purely algebraic, though its consequences reached into topology, analysis, and physics. To understand it, we shall have to revisit a topic, and a place. The topic is group theory; the place, the rocky windswept fjords of Norway.

FIGURE 13-7 A manifold may have many folds, but it is “locally flat” at every point.

§13.7 In §11.6, I mentioned the Norwegian mathematician Ludwig Sylow and the lectures he gave on group theory at Oslo University in 1862. Among those who attended the lectures was a young fellow countryman named Sophus Lie, then just 19 years old. At this point Lie was a full-grown Viking: tall, blond, strong, handsome, and fearless. A keen hiker, he was said to be able to cover 50 miles in a day. That is pretty good over any terrain; over Norwegian terrain, it is phenomenal. Mathematical folklore says that if it started to rain when Lie was hiking, he would take off his clothes and stuff them in his backpack. There is no reference to this, however, in Arild Stubhaug’s meticulous but very respectful biography.142

Although he is now written of as an algebraist, Lie always considered himself to be a geometer. All his work had a geometrical inspira-

tion. In 1869, on the strength of a paper about projective geometry that he published at his own expense, Lie applied to the university for a grant to visit the mathematical centers of Europe. (It was under one of these grants that Ibsen had made his escape from Norway five years earlier.) Lie left Norway in 1869 and was away for 15 months. He went to Berlin, where he struck up a deep and productive friendship with Felix Klein, who was also visiting that city. Klein had seen Julius Plücker’s work on line geometry to publication after Plücker’s death; Lie had read the work in Norway and been greatly influenced by Plücker’s ideas. Lie went to Göttingen too and then to Paris. In Paris he was joined by Klein again, and the two young men—Lie was 27, Klein had just turned 21—went to lectures given by Camille Jordan.

Though slightly older—he was 32—Jordan was of their own intellectual generation. He had trained as an engineer but was a strong mathematical all-rounder. He had just, in the spring of this year, 1870, published the first book ever written on group theory, the Treatise on Algebraic Substitutions and Equations. Jordan’s book did not attain the level of generality of Cayley’s 1854 papers. He wrote of groups as being groups of permutations and transformations. His coverage of the subject was very comprehensive, though, and the Treatise is considered the founding text of modern group theory. How much Lie remembered of Sylow’s 1862 lectures we do not know, but it seems certain that it was those weeks in Paris with Jordan that put groups firmly into his head and into Felix Klein’s, too.

All this happy and, as we shall see, exceptionally productive mathematical fellowship was rudely interrupted on July 19 when the empire of France declared war on the kingdom of Prussia. Klein, a Prussian, had to leave Paris in haste. In mid-August, Lie too left Paris, heading south for Switzerland on foot, with only a backpack. Thirty miles from Paris he was arrested as a German spy, apparently because he was overheard talking to himself in a language that sounded like German.

Examining the contents of Lie’s backpack, the gendarmes found letters and notebooks with German postmarks, filled with cryptic

symbols. Lie protested that he was a mathematician. He was ordered to prove it by explaining some of the notes. According to Stubhaug:

Lie was supposed then to have burst out, saying, “You will never, in all eternity, be able to understand it!” [Words that return an echo from many of us who have tackled Lie Theory …—J.D.] But when he realized what danger he was in, he was said nevertheless to have made an effort, and he began thus: “Now then, gentlemen, I want you to think of three axes, perpendicular to each other, the x-axis, the y-axis, and the z-axis …” and while he drew figures in the air for them with his finger, they broke into laughter and needed no further proof.

Lie nonetheless had to sit in prison for a month reading Sir Walter Scott’s novels in French translation before being allowed to continue to Geneva. When he got back to Christiania in December, he found that he was the 19th-century Norwegian equivalent of a media sensation—the scholar who had been arrested as a spy. The next month he got a research fellowship and lecturing position at the university in Christiania. Shortly afterward, Felix Klein, whose brief service as a medical orderly in the Franco-Prussian War had been curtailed by illness, took up a position as lecturer at Göttingen. Jordan’s Treatise was being read by mathematicians everywhere. The 1870s, the first great decade of group theory, were under way. So was the fifth revolution in geometry to occur in that amazing century: the “groupification” of geometry.

§13.8 In Chapter 11, I described several different kinds of groups. Those were all finite groups, though. Each had just a finite number of elements. Groups can be infinite as well as finite. The family of integers ![]() , with ordinary addition as the rule of combination, forms an infinite group.

, with ordinary addition as the rule of combination, forms an infinite group.

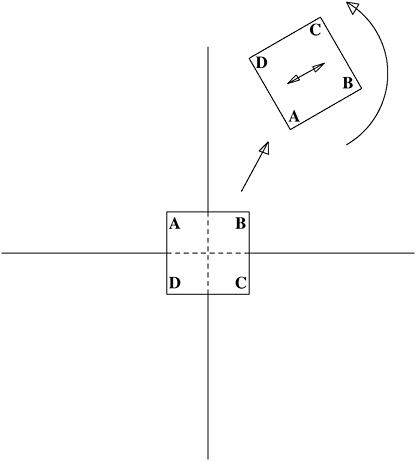

Geometry is rich with examples of infinite groups. In §11.7, I showed the dihedral group D4, a group of eight elements that can be

illustrated by rotating and flipping a square in such a way that it always occupies the same region of two-dimensional space. That is a finite group, but what if I remove the restriction? What if I allow the square to move around the plane in any way at all—sliding to some new position, rotating through any angle at all, flipping over? (See Figure 13-8.) What can be said about that family of motions?

What can be said is that it’s a group! The operation “moving the square to some new position and orientation” satisfies all the requirements of a group operation. If you do it one way, then follow by doing it another way, the combined result is just as if you had done it

FIGURE 13-8 An isometry.

some third way: a × b = c. The associative law a × (b × c) = (a × b) × c obviously applies (“do this, then do the result of doing that-and-that …”); the do-nothing “motion” will serve as an identity, and every movement can be undone—“has an inverse.” It’s a group. (Question: Is it commutative?)

Plainly this is a group with infinitely many members. And if you imagine the square drawn on an infinite transparency, sliding and turning as it moves over the “original” plane, you can see that this is a group of transformations of the entire plane. Its proper name is, in fact, the group of isometries of the Euclidean plane. The word “isometry” is an important one here. From Greek roots meaning “equal measure,” it refers to transformations that “preserve distances.” If two points are a distance x apart, they remain x apart under any isometry. There is no stretching or shearing. The distance between any two points is an invariant under this group of transformations.

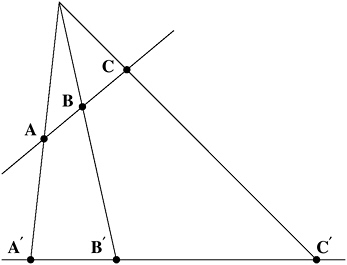

Felix Klein, inspired by his conversations with Lie and Jordan, conceived of a brilliant idea, an idea by means of which the wild jungle growth of geometries that had proliferated in the first 70 years of the 19th century could be unified under a single great organizing principle. The organizing principle should be that a geometry is distinguished by the group of transformations under which its propositions remain true. Two-dimensional Euclidean geometry remains true under the group of plane isometries I just described.143 And characteristic of that group is some invariant—the invariant in this case being the distance between any two points.

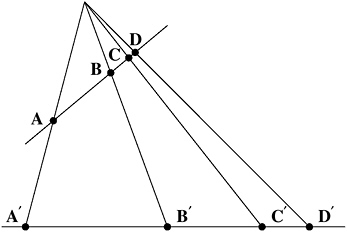

Can we extract some similar group, and characteristic invariant, from projective geometry? From the “hyperbolic geometry” of Lobachevsky and Bolyai? From Riemann’s yet more general geometries? We can indeed. The groups here are not easy to describe, but I can at least show you an invariant in projective geometry. Obviously the distance between two points is not preserved in projective geometry. Less obviously, but as illustrated in Figure 13-9, neither is the ratio of two distances between three points: the ratio AC/AB is 2 on the transparency, but 3 on the projection. If you were to take four

FIGURE 13-9 AC / AB not a projective invariant.

points, though, as in Figure 13-10, and compute the ratio of ratios (AC/AD) / (BC/BD) you would find that it remains the same under projection (in my diagram, it is 5/4), with only some slight, manageable complications when one of the points is projected to infinity. This “cross-ratio” is a projective invariant.

FIGURE 13-10 (AC / AD) / (BC / BD) is a projective invariant.

In the fall of 1872, Klein moved from Göttingen to take up a professorship at Erlangen. It was the custom for a new professor to give an inaugural lecture, a sort of keynote speech for his professorship, laying out the areas of research he intended to encourage. Lie was with Klein in Erlangen for two or three weeks from the beginning of October and helped him work on that speech. In the end, though, Klein did not use this speech for inaugural purposes but published it separately as a paper with the title “Comparative Considerations of Newer Geometric Researches.”

This is one of the great mathematical documents of all time, universally known as the Erlangen program.144 It is not a mathematical paper, in the common sense of one reporting some result or solving some problem. It retains the hortatory quality of an inaugural address, even though Klein did not deliver it at his inauguration. In this program, Klein laid out the idea I sketched above for unifying geometry under the theories of groups and invariants. The program is regarded now, in hindsight, as a bugle call to mathematicians to get busy “group-ifying” their subject.

§13.9 The geometric transformation groups I spoke of in the last section, like the group of isometries in the plane, are not merely infinite; they are continuous, their infinity being of the uncountable kind. You can slide that square along an inch, or a thousandth of an inch, or a trillionth of an inch. You can rotate it through 90 degrees, or 90 one-thousands of a degree, or 90 one-trillionths of a degree. There is no limit to how fine you can “cut” these isometries. They can even be “infinitesimal.” Translation: In admitting these kinds of transformations into the groupish scheme of things, we have opened the door to let calculus and analysis come into group theory, and vice versa.

Klein himself was not deterred by this. At the end of the Erlangen program, he called for a theory of continuous transformation groups as rigorous and fruitful as the theory of finite groups. (“Of groups of

permutations,” is what he actually said. The reader must remember that group theory was still far from mature.)

Lie thought this too ambitious, his role in having inspired the Erlangen program notwithstanding. He was now—we are at the end of 1872—a full professor, the Norwegian government having created a chair of mathematics for him. Having little in the way of teaching duties to distract him, Lie absorbed himself in a problem that had gotten his attention. The problem concerned the solving of differential equations, equations in which the unknown quantity to be determined is not a number but a function. An example would be

which can be solved for y in terms of trigonometric and exponential functions of x. Lie had the idea to treat these equations in a way analogous to the way Galois had treated ordinary algebraic equations, but by using these newer continuous groups in place of the finite groups of permutations in Galois theory.

Having gotten fairly deep into this material at the time Klein came out with the Erlangen program, Lie was inclined to think that the whole subject of transformation groups was too large and tangled to permit the kind of rigorous classification Klein suggested. A year later he had changed his mind. A full general theory of continuous groups, of their actions not merely in the plane but on the most general kind of manifold, and of their consequences for the higher calculus was possible. Lie set out to create that theory, and it bears his name to this day.145

§13.10 With Klein’s announcement of the Erlangen program for the group-ification of geometry, with Lie embarked on his theory of continuous groups, and with Hilbert’s discoveries in ring theory around 1890, the picture of 19th-century algebra and algebraic geometry is almost complete. One country has been missing from my

account, though, and this is inexcusable in a chapter on algebraic geometry.

The nation of Italy, as we know it today, came into existence in the 1860s following the Risorgimento (“re-rising”) movement of national consciousness that flourished through the middle decades of the 19th century. Thus relieved from the distractions of getting themselves a nation, the Italians picked up their grand mathematical tradition, populating the later 19th century with some fine scholars: Enrico Betti, Francesco Brioschi, Luigi Cremona, Eugenio Beltrami.

Riemann’s influence on these Italian mathematicians was strong. When, in the early 1860s, Riemann’s tuberculosis became a hindrance to his work, he traveled to Italy for the warmer air. While in that country he made friends with several mathematicians; it is no coincidence that the student of tensor calculus—the modern development of Riemann’s geometry—soon encounters the names of two end-century Italian mathematicians, Gregorio Ricci and Tullio Levi-Civita.

The Italians were indeed especially strong in geometry. They took the midcentury approach of investigating curves and surfaces for their own interest—“modern classical geometry,” one historian of mathematics146 called it—and brought it into the 20th century. This was the work of a second cohort of Italian geometers born in the 1860s and 1870s: Corrado Segre, Guido Castelnuovo, Federigo Enriques, and Francesco Severi.

By the time the work of these geometers reached maturity, however, algebraic geometry had ceased to be sexy. This was no mere capricious change in mathematical fashion. By the 1910s, logical and foundational problems had begun to appear in “modern classical geometry,” the geometry launched by Poncelet and Plücker a hundred years before. Algebraic geometry was due for an overhaul, via methods presaged by Hilbert and Klein. That overhaul will be one of the topics of my next chapter. Here I only note the achievement of the Italians in keeping algebraic geometry alive while the algebraic tools were prepared for its 20th-century transformation.

The end point of “modern classical geometry” can conveniently be marked, I think, by Julian Lowell Coolidge’s 1931 textbook, A Treatise on Algebraic Plane Curves. Coolidge, born 1873 in Brookline, Massachusetts,147 taught at Harvard for most of his life and was chairman of the mathematics department at that noble institution from 1927 until his retirement in 1940. The epigraph of his book reads:

AI GEOMETRI ITALIANI

MORTI, VIVENTI

(“To the Italian geometers, dead and living”)