Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra (2006)

Chapter: Math Primer: Vector Spaces and Algebras

Math Primer

VECTOR SPACES AND ALGEBRAS

§VS.1 THE HISTORY OF THE CONCEPT vector in mathematics is rather tangled. I shall try to untangle it in the main text. What follows in this primer is an entirely modern treatment, developed in hindsight, using ideas and terms that began to be current around 1920.

§VS.2 Vector space is the name of a mathematical object. This object has two kinds of elements in it: vectors and scalars. The scalars are probably some familiar system of numbers, with full addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division—![]() will do just fine. Vectors are a little more subtle.

will do just fine. Vectors are a little more subtle.

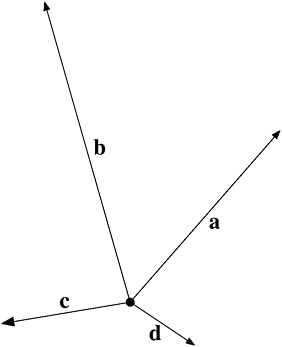

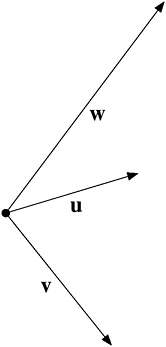

Let me give a very simple example of a vector space. Consider an infinite flat plane. I select one particular point of the plane, which I call the origin. A vector is a line going from the origin to some other point. Figure VS-1 shows some vectors. You can see that the two characteristics of a vector are its length and its direction.

Every vector in this vector space has an inverse. The inverse is a line of the same length as the vector but pointing in the opposite direction (see Figure VS-2). The origin by itself is counted as a vector, called the zero vector.

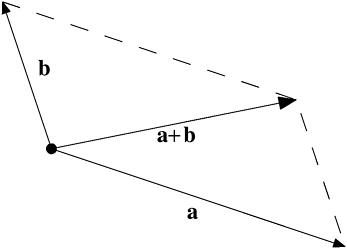

FIGURE VS-3 Adding vectors.

Any two vectors can be added together. To add two vectors, look at them as adjacent sides of a parallelogram. Sketch in the other two sides of this parallelogram. The diagonal proceeding from the origin to the far corner of the parallelogram is the sum of the two vectors. (see Figure VS-3).

If you add a vector to the zero vector, the result is just the original vector. If you add a vector to its inverse, the result is the zero vector.

Any vector can be multiplied by any scalar. The length of the vector changes by the appropriate amount (for example, if the scalar is 2, the length of the vector is doubled), but its direction is unchanged—except that it is precisely reversed when the multiplying scalar is negative.

§VS.3 That’s pretty much it. Of course, the flat-plane vector space I have given here is just an illustration. There is more to vector spaces than that, as I shall try to show in a moment. My illustration will serve for a little longer yet, though.

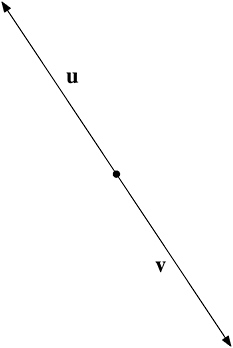

An important idea in vector space theory is linear dependence. Take any collection of vectors in your vector space, say u, v, w, … etc. If it is possible to find some scalars p, q, r, …, not all zero, such that

then we say that u, v, w, … are linearly dependent. Look at the two vectors u and v in Figure VS-4. v points in precisely the opposite direction to u, and is ![]() its length. It follows that 2u + 3v = 0. So u and v are linearly dependent. Another way of saying this is: You can express one of them in terms of the other:

its length. It follows that 2u + 3v = 0. So u and v are linearly dependent. Another way of saying this is: You can express one of them in terms of the other: ![]() .

.

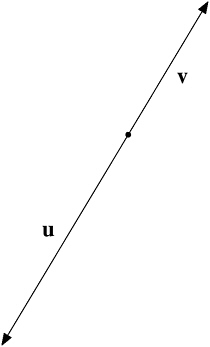

Now look at the vectors u and v in Figure VS-5. This time the two vectors are not linearly dependent. You cannot possibly find any scalars a and b, not both zero, making au + bv equal to the zero vector. (A good way to convince yourself of this is to argue that since a and b can’t both be zero, we can divide through that expression by one of

FIGURE VS-4 Linear dependence.

FIGURE VS-5 Linear independence.

them—say b—to get it in this form: cu + v. Now imagine the diagram for adding u and v, with the parallelogram and its diagonal drawn in—Figure VS-3 above. Leaving v alone, change the size of the u vector by varying c through all possible values, making it as big as you like, as small as you like, zero, or negative—reversing its direction for negative values of c, of course—and watch what happens to the diagonal. It can never be zero.)

The vectors u and v in Figure VS-5 are therefore not linearly dependent. They are linearly independent. You can’t express one in terms of the other. In Figure VS-4, you can express one in terms of the other: v is ![]() .

.

Equipped with the idea of a linearly independent set of vectors, we can define the dimension of a vector space. It is the largest number of linearly independent vectors you can find in the space. In my sample vector space, you can find plenty of examples of two linearly independent vectors, like the two in Figure VS-5; but you can’t find

three. The vector w in Figure VS-6 can be expressed in terms of u and v, in fact the way I have drawn it: w = 2u − v. To put it another way, 2u − v − w = 0. The three vectors u, v, and w are linearly dependent.

Since the largest number of linearly independent vectors I can find in my sample space is two, this space is of dimension two. I guess this is not a great surprise.

In a two-dimensional vector space like this one, if two vectors are linearly independent, they will not lie in the same line. In a space of three dimensions, if three vectors are linearly independent, they will not lie in the same flat plane. Contrariwise, three vectors all lying in the same flat plane—the same flat two-dimensional space—will be linearly dependent, just as two vectors lying in the same line—the same one-dimensional space—will be linearly dependent. Any four vectors all in the same three-dimensional space will be linearly dependent … and so on.

FIGURE VS-6 w = 2u − v.

Given two linearly independent vectors, like u and v in Figures VS-5 and VS-6, any other vector in my sample space can be expressed in terms of them, as I did with w. This means that they are a basis for the space. Any two linearly independent vectors will do as a basis; any other vector in the space can be expressed in terms of them.

Dimension and basis are fundamental terms in vector space theory.

§VS.4 The concept of a vector space is purely algebraic and need not have any geometric representation at all.

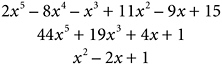

Consider all polynomials in some unknown quantity x, of degree not more than 5, with coefficients in ![]() . Here are some examples:

. Here are some examples:

These polynomials are my vectors. My scalars are just ![]() . This is a vector space. Look, I can add any two vectors to get another vector:

. This is a vector space. Look, I can add any two vectors to get another vector:

Every vector has an inverse (just flip all the signs). The ordinary real number zero will do as the zero vector. And of course, I can multiply any vector by a scalar:

It all works. An obvious basis for this space would be the six vectors x5, x4, x3, x2, x, and 1. These vectors are linearly independent, because

(that is, the zero polynomial) for any value of the unknown x only if a, b, c, f, g, and h are all zero. And since any other vector in the space

can be expressed in terms of these six, no group of seven or more vectors can be linearly independent. The space has dimension 6.

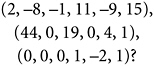

You might grumble that since I am not really doing any serious work on these polynomials—not, for example, trying to factorize them—the powers of x are really nothing more than place holders. What I am really playing with here is just the sextuplets of coefficients. Might I not just as well forget about x and write my three example polynomials as

If I then define addition of two sextuplets in the obvious way,

with scalar multiplication as

wouldn’t this be, in some sense, the same vector space as the polynomial one?

Well, yes, it would. The mathematical object “vector space” is just a tool and an abstraction. We may choose to express it differently—geometrically, polynomially—to give us insights into the particular task we are using it for. But in fact every six-dimensional vector space over ![]() is essentially the same as (mathematicians say “isomorphic to”) the vector space of real-number sextuplets, with vector addition and scalar multiplication as I have defined them.

is essentially the same as (mathematicians say “isomorphic to”) the vector space of real-number sextuplets, with vector addition and scalar multiplication as I have defined them.

§VS.5 Vector spaces, while not very exciting in themselves, lead to much more potent and fascinating consequences when we (a) study their relations with each other or (b) enhance them slightly by adding new features to the basic model.

Under the first of those headings comes the large topic of linear transformations—the possible mappings of one vector space into another, assigning a vector in the second to a vector in the first, according to some definite rule. The word “linear” insists that these mappings be “well behaved”—so that, for example, if vector u maps into vector f and vector v maps into vector g, then vector u + v is guaranteed to map into vector f + g.

You can see the territory we get into here if you think of mapping a space of higher dimension into one of lower dimension—a “projection,” you might say. Contrariwise, a space of lower dimension can be mapped into a space of higher dimension—an “embedding.” We can also map a vector space into itself or into some lower-dimensional subspace of itself.

Since a number field like ![]() or

or ![]() is just a vector space of dimension 1 over itself (you might want to pause for a moment to convince yourself of this), you can even map a vector space into its own scalar field. This type of mapping is called a linear functional. An example, using our vector space of polynomials, would be the mapping you get by just replacing x with some fixed value—say x equals 3—in every polynomial. This turns each polynomial into a number, linearly. Astoundingly (it has always seemed to me), the set of all linear functionals on a space forms a vector space by itself, with the functionals as vectors. This is the dual of the original space and has the same dimension. And why stop there? Why not map pairs of vectors into the ground field, so that any pair (u, v) goes to a scalar? This gets you the inner product (or scalar product) familiar to students of mechanics and quantum physics. We can even get more ambitious and map triplets, quadruplets, n-tuplets of vectors to a scalar, leading off into the theories of tensors, Grassmann algebras, and determinants. The humble vector space, though a simple thing in itself, unlocks a treasure cave of mathematical wonders.

is just a vector space of dimension 1 over itself (you might want to pause for a moment to convince yourself of this), you can even map a vector space into its own scalar field. This type of mapping is called a linear functional. An example, using our vector space of polynomials, would be the mapping you get by just replacing x with some fixed value—say x equals 3—in every polynomial. This turns each polynomial into a number, linearly. Astoundingly (it has always seemed to me), the set of all linear functionals on a space forms a vector space by itself, with the functionals as vectors. This is the dual of the original space and has the same dimension. And why stop there? Why not map pairs of vectors into the ground field, so that any pair (u, v) goes to a scalar? This gets you the inner product (or scalar product) familiar to students of mechanics and quantum physics. We can even get more ambitious and map triplets, quadruplets, n-tuplets of vectors to a scalar, leading off into the theories of tensors, Grassmann algebras, and determinants. The humble vector space, though a simple thing in itself, unlocks a treasure cave of mathematical wonders.

§VS.6 So much for heading (a). What about (b)? What theories can we develop by enhancing a vector space slightly, adding new features to the basic model?

The most popular such extra feature is some way to multiply vectors together. Recall that in the basic definition of a vector space the scalars form a field, with full addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. The vectors, however, can only be added and subtracted. You can multiply them by scalars but not by each other. One obvious way to enhance a vector space would be to add on some consistent and useful method for multiplying two vectors together, the result being another vector.

A vector space with this additional feature—that two vectors can not only be added but also multiplied, giving another vector as the result—is called an algebra.

This is, I agree, not a very happy usage. The word “algebra” already has a perfectly good meaning—the one that is the topic of this book. Why confuse the issue by sticking an indefinite article in front and using it to name this new kind of mathematical object? It’s no use complaining, though. The usage is now universal. If you hear some mathematical object spoken of as “an algebra,” it is almost certainly a vector space with some way to multiply vectors added on to it.

The simplest example of an algebra that is not completely trivial is ![]() . Recall that the complex numbers can best be visualized by spreading them out on an infinite flat plane, with the real part of the number as an east-west coordinate, the imaginary part as a north-south coordinate (Figure NP-4). This means that

. Recall that the complex numbers can best be visualized by spreading them out on an infinite flat plane, with the real part of the number as an east-west coordinate, the imaginary part as a north-south coordinate (Figure NP-4). This means that ![]() can be thought of as a two-dimensional vector space. A complex number is a vector; the field of scalars is just

can be thought of as a two-dimensional vector space. A complex number is a vector; the field of scalars is just ![]() ; zero is the zero vector (0 + 0i, if you like); the inverse of a complex number z is just its negative, −z; and the two numbers 1 and i will serve as a perfectly good basis for the space. It’s a vector space … with the additional feature that two vectors—that is, two complex numbers—can be multiplied together to give another one. That means that

; zero is the zero vector (0 + 0i, if you like); the inverse of a complex number z is just its negative, −z; and the two numbers 1 and i will serve as a perfectly good basis for the space. It’s a vector space … with the additional feature that two vectors—that is, two complex numbers—can be multiplied together to give another one. That means that ![]() is not just a vector space, it is an algebra.

is not just a vector space, it is an algebra.

Turning a vector space into an algebra is not at all an easy thing to do, as the hero of my next chapter learned. That six-dimensional space of polynomial expressions I introduced a page or two ago, for instance, is not an algebra under ordinary multiplication of polynomials. This is why useful algebras tend to have names—there aren’t that many of them. To make an algebra work at all, you may have to relax certain rules—the commutative rule in most cases. That’s the rule that says that a × b = b × a. Often you have to relax the associative rule, too, the rule that says a × (b × c) = (a × b) × c.

If, as well as wanting to multiply vectors together, you also want to divide them, you have narrowed your options down even more dramatically. Unless you are willing to relax the associative rule, or allow your vector space to have an infinite number of dimensions, or allow your scalars to be something more exotic than ordinary numbers, you have narrowed those options all the way down to ![]() ,

, ![]() , and the field of quaternions.

, and the field of quaternions.

Ah, quaternions! Enter Sir William Rowan Hamilton.