Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra (2006)

Chapter: Endnotes

ENDNOTES

Introduction

Math Primer: Numbers and Polynomials

|

6. |

In modern usage, |

|

7. |

The common proof, first given by Euclid, argues reductio ad absurdum. Suppose the thing is not true. Suppose, that is, that some rational number |

|

8. |

Pythagoras’s theorem concerns the lengths of the sides of a plane right-angled triangle. It is a matter of simple observation that the side opposite the right angle must be longer than either of the other two sides. The theorem asserts that the square of its length is equal to the squares of their lengths, added together: c2 = a2 + b2, where a and b are the lengths of the sides forming the right angle and c the length of the side opposite it. Another way to say this, as in Figure NP-4, is |

Chapter 1: Four Thousand Years Ago

Chapter 2: The Father of Algebra

Chapter 3: Completion and Reduction

|

31. |

A right-angled triangle with shorts sides 103 and 159 has, by Pythagoras’s theorem (Endnote 8), a hypotenuse of length |

Math Primer: Cubic and Quartic Equations

Chapter 4: Commerce and Competition

|

|

appear. The term in xn−6, for example, will have coefficient 21 − 13 − 8, which is zero. You are left with Setting x equal to each of the two roots of x2 − x − 1 = 0 in turn eliminates S, giving you a pair of simultaneous equations in two unknowns, un and un−1. Eliminate un−1 and the result follows. |

|

36. |

The binomial theorem gives a formula for expanding (a + b)N. In the particular case N = 4, it tells us that (a + b)4 = a4 + 4a3b + 6a2b2 + 4ab3 + b4, and that’s what I used here. |

|

37. |

Not, as often written, Liber abaci, at any rate according to Kurt Vogel’s DSB article on Fibonacci, to which I refer argumentative readers. The title translates as “The Book of Computation,” not “The Book of the Abacus.” As with the names of operas, the titles of books in Italian do not need to have every word capitalized. |

|

38. |

He was born, in other words, within a year or two of the famous Leaning Tower, construction on which began in 1173, though it was not finished for 180 years. The lean became obvious almost at once, when the third story was reached. |

|

39. |

Nowadays the town of Bejaïa (written “Bougie” in French) in Algeria, about 120 miles east of Algiers. |

|

40. |

Flos is Latin for “flower,” in the extended sense “the very best work of….” |

|

41. |

The scholar-statesman Michael Psellus, who served Byzantine emperors through the third quarter of the 11th century—he was prime minister under Michael VII (1071–1078)—certainly knew of Diophantus’s literal symbolism. |

|

42. |

Full title Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita—“A Summary of Arithmetic, Geometry, Proportions, and Proportionalities.” Note, by the way, that we have now passed into the era of printed books in Europe. Pacioli’s, printed in Venice, was one of the first printed math books. |

|

43. |

A later book of Pacioli’s enjoyed the highly enviable distinction of having Leonardo da Vinci for its illustrator. Da Vinci and Pacioli were close friends. See Endnote 123 for another distinction of this sort. Yet an- |

|

|

other of Pacioli’s claims to fame is that of having coined the word “million.” |

|

44. |

The Italians had just spelled out “plus” and “minus” as piu and meno, respectively; though, like the powers of the unknown, these had increasingly been abbreviated, usually to “p.” and “m.” |

|

45. |

The German algebraists of the 15th and 16th centuries were in fact called Cossists, and algebra “the Cossick art.” The English mathematician Robert Recorde published a book in 1557 titled The Whetstone of Witte, which is the second part of Arithmeticke, containing the Extraction of Roots, the Cossike Practice, with the Rules of Equation. This was the first printed work to use the modern equals sign. |

|

46. |

This book was not published in Cardano’s lifetime. There is a translation of it included as an appendix to Oystein Ore’s biography of Cardano mentioned below (Endnote 48). |

|

47. |

Charles V is the ghostly monk in Verdi’s opera Don Carlos. The title Holy Roman Emperor was elective, by the way. To secure it, Charles spent nearly a million ducats in bribes to the electors. He was the last emperor to be crowned by a pope (in Bologna, February 1530). Most of his contemporaries regarded him as king of Spain (the first such to have the name Charles and therefore sometimes confusingly referred to as Charles I of Spain), though he had been raised in Flanders and spoke Spanish poorly. |

|

48. |

Oystein Ore, Cardano, the Gambling Scholar (1953). Ore’s is, by the way, the most readable book-length account of Cardano I have seen, though unfortunately long out of print. For a very detailed account of Cardano’s astrology, see Anthony Grafton’s Cardano’s Cosmos (1999). There are numerous other books about Cardano, including at least three other biographies. |

|

49. |

They are given in detail in Ore’s book. Ore gives over 55 pages to the Cardano–Tartaglia affair, which I have condensed here into a few paragraphs. It is well worth reading in full. For another full account, though with facts and dates varying slightly from Ore’s (whose I have used here), see Martin A. Nordgaard’s “Sidelights on the Cardan-Tartaglia Controversy, in National Mathematics Magazine 13 (1937–1938): 327–346, reprinted by the Mathematical Association of America in their |

|

|

2004 book Sherlock Holmes in Babylon, M. Anderson, V. Katz, and R. Wilson, Eds. |

Chapter 5: Relief for the Imagination

Chapter 6: The Lion’s Claw

Math Primer: Roots of Unity

|

|

powers of 3 are 3, 9, 27, 81, 243, 729, 2187, 6561, 19683, and 59049. Dividing by 11 and taking remainders: 3, 9, 5, 4, 1, 3, 9, 5, 4, and 1. Not a primitive root. This concept of primitive root is in fact related to the one in my main text, but it is not the same. Since 11 is a prime number, every 11th root of unity is a primitive 11th root of unity, but the primitive roots of 11 in a number-theoretic sense are only 2, 6, 7, and 8. Incidentally, I can now explain that “more restricted sense” of the term “cyclotomic equation.” It is the equation whose solutions are all the primitive nth roots of unity. So in the case n = 6, it would be the equation (x + ω)(x + ω2) = 0, that being the equation with solutions x = −ω and x = −ω2. This equation multiplies out as x2 − x + 1 = 0. |

Chapter 7: The Assault on the Quintic

|

63. |

William Dunham’s book Euler, The Master of Us All (1999) manages to do justice to both the man and his mathematics. |

|

64. |

More properly, the Académie des Sciences, founded in Paris in 1666 by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, part of the great awakening of European science in the late 17th century. Compare Britain’s Royal Society, 1660. The Académie used to meet in the Louvre. |

|

65. |

Galois Theory, p. 19. |

|

66. |

Lagrange is one of the greats, with index score 30 in Charles Murray’s scoring (Human Accomplishment, 2003). Euler leads the field with an index score of 100. Newton has 89, Euclid 83, Gauss 81, Cauchy 34. Poor Vandermonde has index score only 1, and that is probably on account of “his” determinant. |

|

67. |

I am simplifying here to the point of falsehood. Instead of “polynomial,” I should really say “rational function.” I’m going to explain that when I get to field theory, though. “Polynomial” will do for the time being. |

|

68. |

Either J. J. O’Connor or E. F. Robertson, joint authors of the article on Ruffini at the indispensable math Web site of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, www-groups.dcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/~history/index.html. |

Chapter 8: The Leap into the Fourth Dimension

Chapter 9: An Oblong Arrangement of Terms

|

88. |

That is one reason the ancient Chinese written language has such a severely abbreviated style. The classical texts were not so much narrative as mnemonic. Shen zhong zhui yuan, Confucius tells us (Analects, 1.ix). James Legge translates this as: “Let there be a careful attention to perform the funeral rites to parents, and let them be followed when long gone with the ceremonies of sacrifice.” That’s four Chinese syllables to 39 English ones. |

|

89. |

This calendar was the work of Luoxia Hong, who lived about 130–70 BCE. |

|

90. |

George MacDonald Ross, Leibniz (Oxford University Press, 1984). |

|

91. |

Bernoulli numbers turn up when you try to get formulas for the sums of whole-number powers, like 15 + 25 + 35 + … + n5. The precise way they turn up would take too long to explain here; there is a good discussion in Conway and Guy’s Book of Numbers. The first few Bernoulli numbers, starting with B0, are: 1, |

|

92. |

More observations give you better accuracy. Furthermore, the planets are perturbed out of their ideal second-degree curves by each other’s gravitational influence. This accounts for Gauss using six observations on Pallas. Did Gauss know Cramer’s rule? Certainly, but for these ad hoc calculations, the less general elimination method was perfectly adequate. |

|

93. |

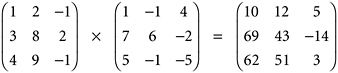

As an undergraduate I was taught to think of this as “diving rows into columns.” To calculate the element located where the mth row of the product matrix meets the nth column, you take the mth row of the first matrix, “tip” it through 90 degrees clockwise, then drop it down alongside the nth column of the second matrix. Multiplying matched-off pairs of numbers and adding up the products gives you the element. Here, for example, is a matrix product, written with proper matrix notation:

|

Chapter 10: Victoria’s Brumous Isles

|

95. |

See Endnote 56. |

|

96. |

Commenting on a different drinking song on a similar theme in his Budget of Paradoxes, De Morgan notes that “in 1800 a compliment to Newton without a fling at Descartes would have been held a lopsided structure.” |

|

97. |

And British affection for it lingered, at least in school textbooks. At a good British boys’ school in the early 1960s, I learned physics and applied mathematics with the Newtonian dot notation. |

|

98. |

The Scot I quoted, Duncan Gregory, only committed himself to mathematics at about the time of that remark and died less than four years later. He was a major influence on Boole, though. In fact, I lifted that Duncan quote not from its original publication (Transactions of the |

|

|

There was no possibility of education in the ordinary sense, but Mrs. Boole’s friendship with [mystic, physician, eccentric, and social radical] James Hinton attracted to the house a continual stream of social crusaders and cranks. It was during those years that Hinton’s son Howard brought a lot of small wooden cubes, and set the youngest three [Boole] girls the task of memorizing the arbitrary list of Latin words by which he named them, and piling them into shapes. [This] inspired Alice [sic] (at the age of about eighteen) to an extraordinarily intimate grasp of four-dimensional geometry….” That Howard, by the way—full name Charles Howard Hinton—was the author of some speculations on the fourth dimension that may have helped inspire Abbott’s Flatland. |

Math Primer: Field Theory

|

|

quadratic equation to F3 This is a particular case of a general theorem: If q = pn, Fq can be constructed by appending to Fp some solution of an irreducible equation of the nth degree. |

Chapter 11: Pistols at Dawn

|

109. |

The Web site is dilip.chem.wfu.edu/Rothman/galois.html |

|

110. |

Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées, though called Journal de Liouville in its early years. Founded in 1836 and still going strong, it boasts itself “the second oldest mathematical journal in the world”—the oldest being Crelle’s, started in 1826. |

|

111. |

Somehow I have forgotten to mention that commutative groups are now called Abelian, in honor of a theorem of Abel’s. Hence the hoary old mathematical joke: “Q—What is purple and commutes? A—An Abelian grape.” It is also customary, when dealing with Abelian groups, to represent the group operation by addition, instead of by the more usual multiplication. The identity element for an Abelian group is therefore often represented by 0 (because 0 + a = a for all a), and the inverse of an element a is written as −a. I shall ignore all this in what follows, to keep things simple. |

|

112. |

Richard Dedekind gave some lectures on Galois theory at Göttingen in the later 1850s. |

|

113. |

More precisely, D3 and S3 are both instances of the same abstract group. The one and only abstract group of order 2, illustrated by my Figure FT-3, has not only D2 and S2 as instances but also C2. Strictly speaking, all such notations as D3, S3, and C2 name particular instances of abstract groups, and we should eschew phrases like “the group S3” in favor of “the group of which S3 is the most familiar instance,” but noone can be bothered to speak that strictly. |

|

114. |

I shall not cover it in any more detail. For a very full and lucid account, see Keith Devlin’s 1999 book, Mathematics, The New Golden Age. For a look at the final tally, though presented at a high level, see The Atlas of Finite Groups by J. H. Conway et al., published by the Clarendon Press, Oxford (1985). |

Chapter 12: Lady of the Rings

|

115. |

This resemblance between integers and polynomials was first noticed, or at any rate first remarked on, by the Dutch algebraist Simon Stevin around 1585. Stevin, by the way—I am sorry I have not found room for him in my main text—was a great propagandist for decimals and did much to make them known in Europe. His book on the subject inspired Thomas Jefferson to propose a decimal currency for the newborn United States, and it is to him (indirectly) that we owe the word “dime.” |

|

116. |

Howls of outrage from professional algebraists here. Yes, I am oversimplifying, though only by a little. In fact, the algebraic notion of a ring is somewhat broader than is implied by the examples I have given. A ring need not, for instance, have a multiplicative identity—that is, a “one”—which both |

|

117. |

As an example of the counterintuitive surprises that ring theory throws up, note that in the ring of numbers having the form |

|

118. |

There is no easy way to define regular primes. The least difficult way is as follows. A prime p is regular if it divides exactly into none of the numerators of the Bernoulli numbers B10, B12, B14, B16, …, Bp−3. (I have notes on the Bernoulli numbers in §9.3 and Endnote 91.) For example: Is 19 a regular prime? Only if it does not divide into any of the numerators of the numbers B10, B12, B14, and B16. Those numerators are 5, 691, 7, and 3617, and 19 indeed does not divide into any of them. Therefore 19 is a regular prime. The first irregular prime is 37, which divides exactly into the numerator of B32, that numerator being 7,709,321,041,217. |

|

119. |

At the time of this writing (April 2005), there has just been an anti-Japanese riot in Beijing, over similar indignities inflicted on China by Japan 60 years ago. |

|

120. |

The town is now in western Poland and renamed Zary. Similarly, Breslau is now the city of Wrocslaw in Poland. The entire German-Polish border was shifted westward after World War II. |

|

121. |

With a dusting of good old Teutonic romanticism. “Poets are we” (Kronecker). “A mathematician who does not at the same time have some of the poet in him, will never be a mathematician” (Weierstrass)—und so weiter. |

|

122. |

Proof. Suppose this is not so. Suppose there is some integer k that is not equal to 15m + 22n for any integers m and n whatsoever. Rewrite 15m + 22n as 15m +(15 + 7)n, which is to say as 15(m + n) + 7n. Then k can’t be represented that way either—as 15 of something plus 7 of something. But look what I did: I replaced the original pair (15 and 22) with a new pair (the lesser of the original pair and the difference of the original pair: 15 and 7). Plainly I can keep doing that in a “method of descent” until I bump up against something solid. It is a matter of elementary arithmetic, proved by Euclid, that if I do so, the pair I shall eventually arrive at is the pair (d, 0), where d is the greatest common divisor of my original two numbers. The g.c.d. of 15 and 22 is 1, so my argument ends up by asserting that k cannot be equal to 1 × m + 0 × n, for any m and n whatsoever. That is nonsense, of course: k = 1 × k + 0 × 0. The result follows from reductio ad absurdum. |

|

123. |

I have depended on the biography by J. Hannak, Emanuel Lasker: The Life of a Chess Master (1959), which I have been told is definitive. My copy—it is Heinrich Fraenkel’s 1959 translation—includes a foreword by Albert Einstein. That is almost as enviable as having Leonardo da Vinci as your book’s illustrator (see Endnote 43). |

|

124. |

There is a Penguin Classics translation by Douglas Parmée. Rainer Werner Fassbinder made a very atmospheric movie version in 1974, with Hanna Schygulla as Effi and Wolfgang Schenck as her husband, Baron von Instetten. |

|

125. |

Aber meine Herren, wir sind doch in einer Universität und nicht in einer Badeanstalt. You can’t help but like Hilbert. The standard English-language biography of him is by Constance Reid (1970). |

|

126. |

To a modern algebraist, “commutative” and “noncommutative” name two different flavors of algebra, leading to different kinds of applications. I can’t hope to transmit this difference of flavor in an outline history of this kind, so I am not going to dwell on the commutative/noncommutative split any more than necessary to get across basic concepts. |

|

127. |

Though for reasons I do not know it was published as a letter to the editor: “The Late Emmy Noether,” New York Times, May 5, 1935. |

Math Primer: Algebraic Geometry

Chapter 13: Geometry Makes a Comeback

Chapter 15: From Universal Arithmetic to Universal Algebra

|

161. |

Professor Swan adds the following interesting historical note: “The homotopy groups were discovered by [Eduard] Cech in 1932, but when he found they were mainly commutative he decided that they were uninteresting, and he withdrew his paper. A few years later, [Witold] Hurewicz rediscovered them, and is usually given the credit.” |

|

162. |

“Pentatope” is the word H. S. M. Coxeter uses for this object in his book Regular Polytopes (Chapter 7). I have not seen the word elsewhere, don’t know how current it is, and do not think it would survive a challenge in Scrabble. As I have shown it, of course, the wire-frame pentatope has been projected down from four dimensions into two, so the diagram is very inadequate. |

|

163. |

A procedure related to the notion of duality that crops up all over geometry. The classic “Platonic solids” of three-dimensional geometry illustrate duality. A cube (8 vertices, 12 edges, 6 faces) is dual to an octahedron (6 vertices, 12 edges, 8 faces); a dodecahedron (20 vertices, 30 edges, 12 faces) is dual to an icosahedron (12 vertices, 30 edges, 20 faces); a tetrahedron (4 vertices, 6 edges, 4 faces) is dual to itself. I ought to say, by the way, in the interest of historical veracity, that it was Emmy Noether who pointed out the advantage of focusing on the group properties here. Earlier workers had described the homology groups in somewhat different language. |

|

164. |

The term “universal algebra” has an interesting history, going back at least to the title of an 1898 book by Alfred North Whitehead, the British mathematician-philosopher of Principia Mathematica co-fame (with Bertrand Russell). Emmy Noether used it, too. My own usage here, though, is only casual and suggestive and is not intended to be precisely congruent with Whitehead’s usage, or Noether’s, or anyone else’s. |

|

165. |

Category theory’s only appearance in popular culture, so far as I know, was in the 2001 movie A Beautiful Mind. In one scene a student says to John Nash: “Galois extensions are really the same as covering spaces!” Then the student, who is eating a sandwich, mumbles something like: “… functor … two categories ….” The implication seems to be that Galois extensions (see my primer on fields) and covering spaces (a topological concept) are two categories that can be mapped one to the other by a functor—quite a penetrating insight. |

|

166. |

Allyn Jackson quotes some revealing remarks about this by Justine Bumby, with whom Grothendieck was living at the time: “His students in mathematics had been very serious, and they were very disciplined, very hard-working people…. In the counterculture he was meeting people who would loaf around all day listening to music.” |

|

167. |

The Grothendieck Biography Project, at www.fermentmagazine.org/home5.html. |

|

168. |

Both the Lorentz group and the one used by Gell-Mann to organize the hadrons—technically known as the special unitary group of order 3—can be modeled by families of matrices, though the entries in the matrices are complex numbers. |

|

169. |

The precise definition, just for the record, is “A Riemannian manifold admitting parallel spinors with respect to a metric connection having totally skew-symmetric torsion.” |

|

170. |

Yau, winner of both a Fields Medal and a Crafoord Prize, was a “son of the revolution,” born in April 1949 in Guangdong Province, mainland China. Following the great famine and disorders of the early 1960s, his family moved to Hong Kong, and he got his early mathematical education there. He is currently a professor of mathematics at Harvard. |

|

171. |

Printed up as “Mathematics in the 20th Century” in the American Mathematical Monthly, 108(7). |

|

172. |

The sense here is that Newton was the absolute-space man, while Leibniz was more inclined to the view that, as the old ditty explains: Space Is what stops everything from being in the same place. |

|

173. |

It is a common misconception that Einstein banished all absolutes from physics and hurled us into a world of relativism. In fact, he did nothing of the sort. Einstein was as much of an “absolutist” as Newton. What he banished was absolute space and absolute time, replacing both with absolute space-time. Any good popular book on modern physics should make the point clear. Einstein’s close friend Kurt Gödel was, by the way, a strict Platonist: The two pals were yin and yin. |