Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra (2006)

Chapter: Math Primer: Roots of Unity

Math Primer

ROOTS OF UNITY

§RU.1 IN MY PRIMER ON THE SOLUTION of the general cubic, I mentioned the cube roots of 1 (§CQ.4). There are three of these little devils. Obviously 1 itself is a cube root of 1, since 1×1×1 = 1. The other two cube roots of 1 are

They are conventionally called ω and ω2, respectively. If you cube either of these numbers—try it, remembering of course that i2 = −1—you will find that the answer is indeed 1 in either case. Furthermore, the second of these numbers is the square of the first, and the first is the square of the second. ω2 is of course the square of ω. Only a bit less obviously, ω is the square of ω2 (because the square of ω2 is ω4 which is ω3 × ω and ω3 is 1, by definition).

§RU.2 The study of the nth roots of 1—“of unity,” we more often say—is very fascinating, and touches on several different areas of math, including classical geometry and number theory. It became

possible only when mathematicians were at ease with complex numbers, which is to say from about the middle of the 18th century. The great Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler broke it wide open in 1751 with a paper titled “On the Extraction of Roots and Irrational Quantities.”

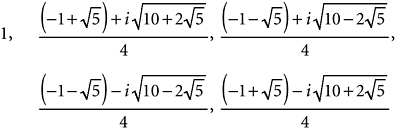

The square roots of 1 are of course 1 and −1. The cube roots of 1 are 1 and the two numbers I gave above, ω and ω2. The fourth roots of 1 are 1, −1, i, and −i. Any one of those will, if you raise it to the fourth power, give you 1. Euler showed that the fifth roots of unity are as follows:

Numerically speaking, these work out to: 1, 0.309017 + 0.951057i, −0.809017 + 0.587785i, −0.809017 − 0.587785i, 0.309017 − 0.951057i. If you plot them on the usual complex-number plane, their real parts plotted west-east and their imaginary parts plotted south-north, they look like Figure RU-1.

They are in fact the vertices of a regular pentagon with center at the origin. To put it another way, they lie on the circumference of the unit circle—the circle with radius 1—and they divide that circumference into five equal arcs. If you use Greek words to devise an English term meaning “dividing up a circle,” you get “cyclotomic.” These complex numbers—points of the complex plane—are called cyclotomic points.61

§RU.3 Where did all those numbers come from? How do we know that the complex cube roots of 1 are those numbers ω and ω2 spelled out above? By solving equations, that’s how.

FIGURE RU-1 The fifth roots of unity.

If x is a cube root of 1, then of course x3 = 1. To put it slightly differently, x3 − 1 = 0. But this is just a cubic equation, which we can solve. In fact, since we know that x = 1 must be one of the three solutions, we can factorize it right away, to this form:

So to get the other two roots, we just have to solve that quadratic equation. The solutions are ω and ω2 just as I described them, from the ordinary quadratic formula (see Endnote 14).

It is generally true, in fact, that the equation whose solutions are the nth roots of unity, the equation xn − 1 = 0, can be factorized like

and then all the other nth roots of unity—other than 1 itself, I mean—are gotten by solving the equation

The solution of this equation for general values of n provided 18th- and 19th-century mathematicians with a good deal of employment. Carl Friedrich Gauss gave over a whole chapter of his great 1801 classic Disquisitiones Arithmeticae to it—54 pages in the English translation. It is sometimes called the cyclotomic equation of order n, though most modern mathematicians use the term “cyclotomic equation” in a more restricted sense.

§RU.4 The crowning glory of Gauss’s investigation was a proof that the regular heptadecagon (that is, a 17-sided polygon) can be constructed in the classical style, using only a ruler and compass.

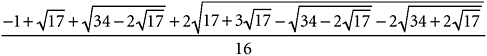

In the terms in which I have been writing, a regular polygon can be so constructed if and only if the cyclotomic points making up its vertices in the complex plane can be written out with only whole numbers and square root signs. This is the case for n = 5, as my display of the fifth roots of unity above show clearly. So a regular pentagon can be constructed with ruler and compass. So, Gauss proved, can a regular heptadecagon. In fact, he wrote out the real part of one of the 17th roots of unity:

Nothing but whole numbers and square roots, albeit “nested” three deep, and therefore constructible by ruler and compass. This was the young Gauss’s first great mathematical achievement and one so famous that a heptadecagon is inscribed on a memorial at his birthplace of Braunschweig, Germany.

Gauss showed that the same thing is true for any prime (not, as is occasionally said in error, any number) having the form ![]() . When k = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, this works out to 3, 5, 17, 257, 65537, all prime numbers. When k = 6, however, you get 4294967297, which is, “as the

. When k = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, this works out to 3, 5, 17, 257, 65537, all prime numbers. When k = 6, however, you get 4294967297, which is, “as the

distinguished Euler first noticed” (I am quoting Gauss) not a prime number.

§RU.5 The roots of unity have many interesting properties and connect not only to classical geometry but to the theory of numbers—of primes, factors, remainders.

For a glimpse of this, consider the sixth roots of unity. They are 1, −ω2, ω, −1, ω2, and −ω where ω and ω2 are the familiar (by now, I hope) cube roots of unity. If you take each one of these sixth roots in turn and raise it to its first, second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth powers, the results are as follows. The roots, denoted by a generic α in the column headings, are listed down the left-hand column. The first, second, etc., powers of each root can then be read off along each line. (The first power of any number is just the number itself. The sixth power of every sixth root is of course 1.)

|

α |

α1 |

α2 |

α3 |

α4 |

α5 |

α6 |

|

1: |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

−ω2: |

−ω2 |

ω |

−1 |

ω2 |

−ω |

1 |

|

ω: |

ω |

ω2 |

1 |

ω |

ω2 |

1 |

|

−1: |

−1 |

1 |

−1 |

1 |

−1 |

1 |

|

ω2: |

ω2 |

ω |

1 |

ω2 |

ω |

1 |

|

−ω: |

−ω2 |

ω2 |

−1 |

ω |

−ω2 |

1 |

Only two of the sixth roots, −ω2 and −ω, generate all the sixth roots in this process. The others just generate some subset of them. This agrees with intuition, since while −ω2 and −ω are only sixth roots of unity, the others are also square roots (in the case of −1) or cube roots (in the case of ω and ω2) of unity.

Those nth roots of unity like −ω2 and −ω in the case of n = 6, whose successive powers generate all the nth roots, are called primitive nth roots of unity.62 The “first” nth root (proceeding counter-

clockwise around the unit circle in the complex-number diagram) is always primitive. After that the other primitive nth roots are the kth ones, for every number k that has no factor in common with n. The primitive ninth roots of unity, for example, would be the first, second, fourth, fifth, seventh and eighth. If n is a prime number, then every nth root of unity, except for 1, is a primitive nth root of unity. And here we are, as I promised, in number theory, speaking of primes and factors.