Gender Differences at Critical Transitions in the Careers of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Faculty (2010)

Chapter: 4 Professional Activities, Institutional Resources, Climate, and Outcomes

4

Professional Activities, Institutional Resources, Climate, and Outcomes

Once Ph.D.s have been hired into an academic position, it is natural to ask, what happens next? The milestones of an academic career are hiring, tenure, and promotion. In the context of these decisions, a primary question must be whether male and female faculty are treated similarly while they are employed. Is the day-to-day experience of being a faculty member similar for men and women?

Equitable treatment and opportunity are important for several reasons. First, how a faculty member is treated affects the ability of that faculty member to do the best research and teaching of which he or she is capable. This in turn affects subsequent decisions on the part of the university about salary, tenure, and promotion. It also affects subsequent decisions on the part of the faculty member about whether to entertain outside offers and whether to leave that university for a position elsewhere. Furthermore, the equitability with which a faculty member is treated can contribute powerfully to whether a faculty member feels he or she is a central part of the enterprise, as well as to the faculty member’s sense of well-being and satisfaction with his or her professional life.

As noted in Chapter 1, there was anecdotal evidence that women do not fare as well as men professionally, but such differences can be subtle and hard to detect. The survey data presented in this report will provide information that is relevant to this perception and will help clarify the current status for women in the six disciplines surveyed at research-intensive (Research I or RI) institutions. According to one commentator:

The study initiated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) several years ago by Nancy Hopkins has now been replicated at several other institutions, including Cal Tech. The reports have shown that women in science and

engineering faculty are more likely to report that they feel marginalized and isolated at their institution, have less job satisfaction, have unequal lab space, unequal salary, unequal recognition through awards and prizes, unequal access to university resources, and unequal invitations to take on important administrative responsibilities, especially those that deal with the future of the department or the research unit. The fact that this study has been replicated at other institutions says that this is not an MIT specific problem. This is a generalized problem about the way women faculty at research-intensive universities experience their career environment. (Tilghman, 2004:9)1

This chapter examines variables that could contribute to a faculty member’s ability to excel at teaching and research. It asks about factors related to equitable treatment of male and female faculty at research-intensive institutions in the six disciplines surveyed, whether there are gender differences in salary, publications, or the inclination to remain at that university, and whether differential treatment accounts for any gender differences in salary, publications, or the inclination to move on. The variables of primary interest to us fall into three categories: professional life, institutional resources, and climate. Under professional life, we include how much of each of the following a faculty member does: the amount of research; the amount of teaching, advising, supervising, and mentoring; and the amount of service to the university or broader community. Under institutional resources sometimes provided to support a faculty member’s teaching and research, we include start-up funds, summer salary, travel funds, reduced teaching loads, laboratory space and equipment, and staff (postdocs, research assistants, clerical support). Under climate, we include variables that can contribute to a faculty member’s sense of engagement or marginalization within the department and the institution, such as whether the faculty member is mentored by more experienced colleagues, whether the faculty member is asked to contribute to important decisions in the department and the university, and whether a faculty member regularly engages in conversation about research and teaching with his or her colleagues.

Three initial comments are necessary prior to proceeding with the assessment. First, there are dozens of factors that together comprise a faculty member’s job, from the number of students she teaches, to whether she has the newest equipment in her lab, to whether she thinks her peers are collegial. One major benefit that studies of hiring, tenure, and promotion have is that there is a dichotomous end point that helps to focus attention. The study of professional activities, institutional resources, climate, and outcomes lacks this. Therefore, anchoring the analysis is somewhat more challenging. Second, the following analysis is descriptive. Essentially, what is reported here about professional life, institutional resources, and climate is the average response of male and female faculty to a

series of questions about their work habits and environment. In the final section of this chapter, we look at how professional life, institutional resources, and climate contribute to important outcomes, such as research productivity and salary. In these analyses, we attempt to control for as many factors as we can that might contribute to the outcome, but it is likely that there are additional relevant variables about which we have no data. Without all relevant controls accounted for in the analysis, the results need to be taken as preliminary and as an impetus for further, more sophisticated research, rather than a definitive statement on the existence of disparities between male and female faculty. Finally, it should be noted that the analyses presented here provide an aggregated, often average, view. That view is not inconsistent with some women having very few resources and some women having quite a lot, nor does it negate the possibility that individual women (or men) are discriminated against in their access to resources. The deviation around average individual accounts of satisfaction or dissatisfaction can reflect a difficult reality, even when the averages among male and female faculty are the same.

The next three sections focus on professional activities, institutional resources, and climate issues. Professional activities include teaching, research, and service. Institutional resources cover a gamut of variables, including lab space, start-up packages, and research assistants. Climate focuses on such issues as mentoring and collegiality. Several of the above factors are further disaggregated into a variety of component elements. To study whether male and female faculty members reported different experiences on these dimensions and variables, we examine four types of information. First and foremost is our survey of faculty in six disciplines in RI institutions.2 A second valuable resource is the U.S. Department of Education’s National Survey of Postsecondary Faculty (NSOPF), undertaken in 2004 (“NSOPF:04”).3 That survey queried respondents regarding the fall 2003 term and thus occurred in a similar timeframe as the faculty survey. The other two information sources used throughout the chapter are individual research studies undertaken by scholars and gender equity reports completed by RI institutions.

After reviewing the three elements of day-to-day careers, we turn our attention to faculty outcomes. In the fourth section, we ask whether there are differences between male and female faculty in publication rates, grant funding, laboratory space (which is both an institutional resource and an outcome), nominations for honors and prizes, salary, outside offers, or the inclination to remain at the current institution, and which professional life qualities, institutional resources,

or climate variables contribute to differences in these outcome variables. This section draws on research done by individuals or as part of institutional studies to examine the issues of retention and job satisfaction, as our survey did not gather data on these variables.

PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES

In this section, we examine the three key areas of professional activities that characterize the day-to-day job of a faculty member: teaching, service, and research. Different departments weigh the value of these three activities differently, but in the Research I institutions, research is likely to be a primary concern. It is commonly believed that women spend more time teaching or performing service-related activities and less time on research than male faculty.

A note about time spent in professional activities is necessary. There are two ideas here: how many hours male and female faculty work and how they divide up the time they spend. Several studies have looked at the number of hours male and female faculty work and have found they tend to work long hours and similar numbers of hours. For example, a self-assessment conducted by the University of Pennsylvania found both men and women work nearly 60 hours per week. The NSOPF:04 found that full-time, professoriate faculty at Research I institutions in science and engineering (S&E) worked about 58 hours per week on average (58.5 for women and 58.1 for men).4 Rather than ask faculty members how many hours they work, our survey asked respondents how they divide their time among research, teaching, and service. That is what we report here.

Research

It is often assumed that men spend a greater percentage of their time doing research than women. The percentage of time spent on research or scholarship was combined with percentage of time spent seeking funding in our survey data. Overall, men reported spending a slightly greater percentage of their time on research activities than women: 42.1 compared to 40.0 percent. This difference, while approaching significance, is quite small in absolute terms. Drawing on similar faculty from the NSOPF:04, there was no significant difference between men and women in the time spent on research activities: 43.2 compared to 39.7 percent.5

|

4 |

Data was created using the Department of Education’s Data Analysis System (DAS) available online at http://www.nces.ed.gov/dasol/. Gender was used as the row variable. The column variable was average total hours per week worked. Filters were only Research I institutions; full-time employed; with faculty status; assistant, associate, or full professors; with instructional duties for credit; and with principal fields of teaching as engineering, biological sciences, physical sciences, mathematics, and computer sciences. |

|

5 |

See previous footnote on how the DAS analysis was conducted. |

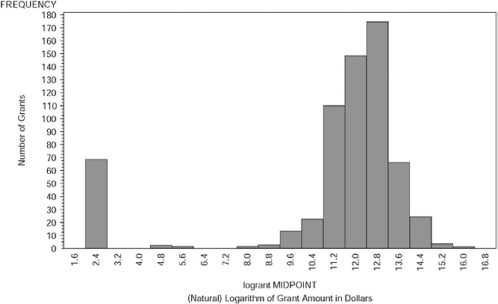

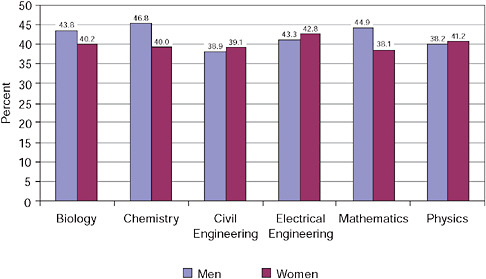

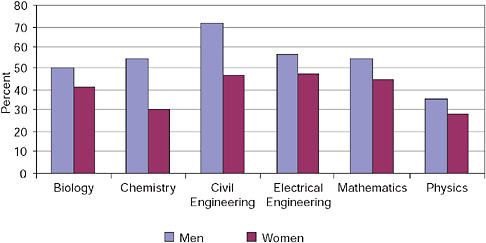

FIGURE 4-1 Mean percentage of time faculty spent on research (self-reported) by gender.

SOURCE: Faculty survey carried out by the Committee on Gender Differences in the Careers of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Faculty.

It is worth noting that the overall percentage of time faculty report spending on research activities is remarkably similar in the two surveys.6

Figure 4-1 shows the reported percentage time spent by faculty in research activities (including preparation of grant and contract proposals) disaggregated by gender and by discipline. Averages were computed over faculty who provided this information on the survey. To investigate whether there are differences in the percentage of time spent in research across disciplines or across genders, we fitted a simple linear model with percent time as the response variable and with discipline, gender, and the interaction between discipline and gender as the effects. We found no significant differences in percentage time spent in research, either across disciplines or between genders within discipline. Because comparing genders within discipline involved carrying out six comparisons, we used the Tukey-Kramer approach7 to adjust the individual p-values. The smallest of the six p-values was obtained when comparing men and women faculty in chemistry (p-value = 0.217). All other p-values were above 0.35. Please note that discipline and gender accounted for a very small (about 2 percent) proportion of the variability observed in self-reported time spent in research activities. Thus, these p-values

are to be interpreted cautiously. A model in which other potential confounders are also included is presented later in this chapter.

In the NSOPF:04 data, there were no significant gender differences in any of the aggregated disciplinary groups reported (biology, physical sciences, mathematics, and computer science).

Teaching

In this section, the percentage of time spent on teaching, the number of classes taught, and the number of students advised are examined for gender differences. It is often assumed that female faculty spend a greater percentage of their time on instructional duties than male faculty.

Using the data from our faculty survey, the percentages of time men and women spent teaching and advising undergraduate and graduate students were combined and the average percentages were compared for men and women. Overall, female and male respondents reported spending approximately the same percentage of time on teaching and advising (men, 41.4 percent; women, 42.6 percent). The NSOPF:04 provided similar data: 44.2 percent for men and 42.0 percent for women. Here again, the percentages in the two surveys are remarkably similar.

Disaggregated by field, the difference between men and women faculty is approaching significance in chemistry and civil engineering, with women reporting more time spent on teaching and advising than men. In the NSOPF:04 data, there were no significant differences between men and women in the aggregated fields reported (biology, physical sciences, mathematics, and computer science).

Amount of Teaching

Our faculty survey also asked respondents how many undergraduate courses they were teaching in the current term/semester. In general, answers ranged from zero to two. There were no significant differences in the average number of undergraduate courses men and women were teaching (men, 0.83 courses; women, 0.82 courses; see Appendix 4-1). The NSOPF:04 data presented a similar picture, with a lower average number of undergraduate courses for women (men, 0.7 courses; women, 0.6 courses).

Looking at each of the six disciplines we surveyed, men were teaching marginally more undergraduate courses than women in electrical engineering; none of the other fields had significant differences between men and women. In the NSOPF:04 data, there were no significant gender differences in the teaching of undergraduate courses in the biological sciences, physical sciences, mathematics, and computer science. (There were too few cases to do this analysis for engineering faculty.)

The above analyses were repeated for graduate courses. Faculty teach fewer graduate courses, so here the distinction is between faculty who were doing no

graduate teaching in the current term or semester and faculty who were doing some graduate teaching in the current term or semester. There was no significant difference found between men and women in terms of whether they were teaching graduate courses in our data (percent doing no graduate teaching: men, 50.8; women, 54.9; see Appendix 4-2.) or in the NSOPF:04 data (percent doing no graduate teaching: men, 46.8; women, 47.3).

There was no significant difference in any of the six fields we surveyed between men and women faculty in terms of whether they are teaching graduate courses. The data approaches significance in physics, where men are less likely to be teaching graduate courses than women. We conducted a similar analysis of the NSOPF:04 data and found that men were significantly more likely to be teaching graduate courses in the biological sciences (men, 65.8 percent; women, 59.7 percent) and in the physical sciences (men, 37.3 percent; women, 29.6 percent). In mathematics and computer science, there was no significant difference between men and women in terms of whether they taught graduate courses (men, 52.9 percent; women, 55.4 percent). (There were too few cases to conduct this analysis for engineering faculty.)

Finally, we explored whether gender is associated with the number of graduate thesis or honor thesis committees on which a faculty member serves. These data are shown in Appendix 4-6, and from the table, we see that the number of thesis committees on which faculty report serving is quite variable, ranging from zero all the way to 30. There appear to be some differences between men and women in terms of the numbers of committees on which they serve, but these differences appear to vary by discipline.8 The NSOPF:04 asked faculty how many hours they spent on thesis and dissertation committees, and men spent marginally more time than women (men, 1.8 hours; women, 1.3 hours).

Service

There is a general awareness that female faculty spend a greater proportion of their time serving on departmental, school, or university-wide committees than men. In looking at the percentage of time faculty spend on service work, we combined the percentage of time spent on administration or committee work within the university with service outside the university. Overall, there was no difference between men and women in the percentage of time spent on service (men, 14.4 percent; women, 15.4 percent; see Appendix 4-7.). The NSOPF:04 found similar percentages of time spent on service, with no difference between men and women faculty (men, 16.1 percent; women, 14.8 percent).9

Disaggregated by field, there appear to be no gender differences in the percentage of time spent on service in any of the six fields we surveyed (see Appendix 4-7). The NSOPF:04 found similar results (biology—men, 15.8 percent, women, 15.3 percent; physical sciences—men, 16.2 percent, women, 12.0 percent; and mathematics and computer science—men, 14.4 percent, women, 14.1 percent).

Committee Service

In addition to asking about the percentage of time spent on service, our faculty survey asked respondents how many committees they have served on. The view is that, in order to make committees more diverse, women are more frequently asked to serve on them, with the result that they serve on more committees than men do. The faculty survey asked respondents if they had participated in 10 types of departmental committees: undergraduate curriculum, graduate curriculum, executive, promotion and tenure, faculty search, fellowship, graduate admissions, facilities or space, program review, and “other.” An initial variable was created that summed participation on the nine identified committees. While the actual range was between zero and nine, few faculty served on more than six committees, and disaggregated by field, there were many cells which contained no faculty members. Therefore, faculty members who served on six or more committees were aggregated into one category of those serving on six or more committees, so that at least one faculty member fit into each cell when the respondents were disaggregated by gender and field. Overall, the average number of committees served on was similar for men (1.61 committees) and women (1.76 committees) (see Appendix 4-8).

INSTITUTIONAL RESOURCES

This section focuses on a single, general question: do male and female faculty receive similar institutional resources? To explore this question, we examine a number of different resources. In order, they are start-up packages received on joining a department, summer salary, travel funds, reduced teaching loads, lab space, equipment, and support staff, including access to graduate research assistants (RAs) and postdocs.

Start-up Funds

Start-up packages are given to new faculty hires. A number of elements can be found in start-up packages, which makes it important to define clearly what is being quantified. Systematic surveys of start-up funds began in earnest around 2000. Examples include surveys conducted by the University of Colorado at Boulder in 1999 and surveys conducted by the Council of Colleges of Arts & Sciences—the New Hires Survey and the 2000 Big 10+ Chemical Engineer-

ing Chairs Survey. Summarizing their data, Ehrenberg and Rizzo (2004) write, “at research universities, these [start-up packages needed to attract new faculty members in the sciences] cost an average of $300,000 to $500,000 for assistant professors and often well over $1 million for senior faculty.” A survey of start-up funds conducted by the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute (CHERI) in 2002 found:

At the new assistant professor level, with few exceptions, Carnegie Research I universities provide larger start-up packages than other universities in the sample, and private research universities provide larger start-up packages than public universities. When the departments are broken down into four broad fields, physics/astronomy, biology, chemistry, and engineering, the average reported start-up package for new assistant professors at private Research I universities varied across fields between $337,000 and $475,000. Estimates of the average high-end (most expensive) assistant professor start-up package costs at these institutions varied across fields from $587,000 to $725,000.10

The data on start-up funds that is disaggregated by gender has been collected by individual institutions. A 2003 task force report at Princeton University, which collected data from five S&E departments, concluded “in the five departments examined, we found no statistical support for gender differences in start-up space, current space, or start-up financial packages. However, we did detect certain patterns. For example, the largest start-up packages have generally gone to men.”

Both the committee’s faculty survey and departmental survey requested data on start-up costs. On the faculty survey, faculty who were tenured or tenure-track and hired after 1996 were asked, “When you were first hired at this institution, how much were you given in start-up funds?” Respondents were asked to break down start-up costs into four categories: equipment, renovation of lab space, staff (e.g., postdocs), and other.

Summer Salary

The faculty questionnaire asked tenure-track or tenured faculty hired after 1996 whether they received summer salary funds when they were first hired at their current institution. Of those who responded, 71 percent of men and 68 percent of women indicated they did. When disaggregated by discipline, interesting differences appeared, with female faculty having a higher percentage in chemistry (81.8 percent compared to 71.2 percent for male faculty) who received summer

|

10 |

The 2002 Cornell Higher Education Research Institute (CHERI) Survey on Start-up Costs and Laboratory Allocation Rules: Summary of the Findings is available at http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/cheri/surveys/2002surveyResults.html, accessed October 7, 2008. See also the presentation by Ronald G. Ehrenberg, Michael J. Rizzo, and George H. Jakubson, “Who Bears the Growing Cost of Science at Universities?” presented at the 2003 Conference. See also Ronald G. Ehrenberg, Michael J. Rizzo, and Scott S. Condie, “Start-up Costs in American Research Universities,” CHERI working paper, WP-33, March 2003, Cornell University. |

salary; while in mathematics the reverse was true, with 42.9 percent of male faculty as contrasted with 29.1 percent of female faculty (see Appendix 4-10).

Travel Funds

The faculty questionnaire asked tenure-track or tenured faculty hired after 1996 whether they received travel funds when they were first hired at their current institution. Of those who responded, 56 percent of men and 59 percent of women indicated that they did (see Appendix 4-11). Again, there was no substantial gender difference at this level of aggregation. There were some differences for men and women among the six disciplines in terms of the percentages of people receiving travel funds initially.

The survey also asked faculty respondents, “During the last five years, have you been given travel money by your department or institution to attend professional conferences or to conduct research offsite?” Of those who answered, approximately 42 percent of men and 43 percent of women answered yes.

Reduced Teaching Loads

Faculty may negotiate a reduced teaching load for an initial period after they are hired. New faculty often desire a reduced teaching load to allow them time to get settled in a new environment and to get their labs and their research set up and underway. The committee’s survey asked all tenure-track and tenured faculty hired after 1996 whether they had received a reduced teaching load when hired. A large majority of new faculty reported receiving a reduced teaching load when they were hired (see Appendix 4-3). However, there was not a significant difference between men and women, in terms of the percentage who received a reduced teaching load when hired in any of the six fields surveyed.

Lab Space

Much of the discussion on lab space stems from the 1999 MIT report, Report of the School of Science, which found an “unequal distribution” of resources, including lab space, allocated to women.11 This focused attention on the issue, and a number of other gender equity assessments at other universities have taken it up.12

Stanford’s report, for example, found no disparity in lab space: “The Provost’s Advisory Committee on the Status of Women Faculty on Thursday issued a variety

|

11 |

Sara Rimer, “For Women in Science, Slow Progress in Academia,” New York Times, April 15, 2005. |

|

12 |

See, for example, a thorough assessment conducted by New Mexico State University in 2003, “Space Allocation Survey,” available at http://www.advance.nmsu.edu/Documents/PDF/ann-rpt-03.pdf. |

of recommendations to strengthen the recruitment and retention of women faculty and, in a first-ever comprehensive analysis, has preliminarily found ‘insignificant’ differences between men and women in benefits and support such as laboratory space, equipment, start-up funds, research funds, and summer salaries” (James Robinson, Report: ‘No Pattern’ of Disparity Between Men, Women Faculty, Stanford Report, May 20, 2003).13 The University of Pennsylvania found mixed results: “With respect to the professional status of women faculty, the committee determined that at the more junior ranks women had more research space per grant dollar than men, but women full professors averaged somewhat less space per grant dollar14 than their male colleagues; in both SAS science departments and the School of Medicine, senior women faculty had about 85 percent of the space assigned to males.”15 Case Western Reserve found women had less lab space: “Despite these heavier workloads, participants believe that women often receive fewer benefits and support resources. Women tend to enter the university with more limited start-up packages…. They receive less space, have less access to graduate student assistance, and get fewer services from support staff.”16

However, quantitative data on lab space are hard to find. It is critical that it be measured, because, as Purdue’s report noted, it may be a perceptual or an actual discrepancy:

Females responded differently than males on a number of these issues. However, most differences appear to simply reflect perceptual differences across the schools and the varying distribution of women in the schools (e.g., women are less satisfied than men with library resources, but this largely reflects the fact that Education and Liberal Arts schools, where faculty are the least satisfied with library resources, are also schools with relatively high proportions of women faculty).

Taking into account these differences in gender representation across the schools, females are still less likely to believe that they have adequate laboratory space (48 percent) than are males (60 percent). In particular, women in agriculture, health sciences, and science are substantially less likely than their male counterparts to feel that they have adequate lab space.17

|

13 |

Available at http://news-service.stanford.edu/news/2003/may21/womenfaculty-521.html. |

|

14 |

Note that the University of Pennsylvania’s research used an unusual metric of research space per grant dollar. |

|

15 |

University of Pennsylvania Gender Equity Committee, “The Gender Equality Report, Executive Summary, Almanac, Vol. 48, No. 14, December 4, 2001, available at http://www.upenn.edu/almanac/v48/n14/GenderEquity.html. See the full report at: http://www.upenn.edu/almanac/v48pdf/011204/GenderEquity.pdf. |

|

16 |

CWRU Equity Study Committee, “Resource Equity at Case Western Reserve University: Results of Faculty Focus Groups,” March 3, 2003, pp. 46-47. Available at http://www.case.edu/president/aaction/resourcequity2003.doc. |

|

17 |

Purdue conducted a survey in 2001, which asked female and male faculty whether they were satisfied with the amount of lab space. Women were less satisfied. (This is different from how much lab |

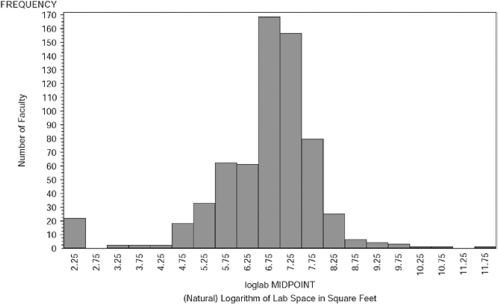

The committee’s survey asked faculty to identify how much lab space they have. It should be noted that lab space may mean different things to different people and in different disciplines. One problem, for example, is how to count shared lab space. Overall, lab square footage ranged from zero to 100,000 square feet. The two largest figures—47,000 and 100,000—both occurred in civil engineering and appear to be outliers.18 Both observations were changed to missing. Estimated lab space was reported by 769 respondents. Overall, men reported significantly more lab space, with an average of about 1,550 square feet, than women, with an average of about 1,160 square feet. Disaggregated by field (see Figure 4-2), men had significantly more lab space in civil engineering and physics and marginally more in biology.19

One concern about studying lab space is that some faculty are theoretical while others are experimental, and the former might not need a lot of lab space. As the Report of the Task Force on the Status of Women Faculty in the Natural Sciences and Engineering at Princeton (2003:24) noted:

Experimental science is heavily resource dependent. Consequently, in many departments, an individual’s success is highly dependent on his/her access to space, equipment, supplies, students, postdoctoral fellows, and other laboratory personnel. At the time faculty members are hired, experimentalists are given laboratory space and start-up funds, which are used to purchase equipment and supplies as well as to support personnel. Funds for future support of the lab usually come from research grants, which are obtained from external, not University, funding. For faculty hired at the assistant professor level, additional laboratory space is usually needed to allow growth of research programs. Most experimentalists also require expensive equipment (e.g., electron microscopes, mass spectrometers, multi-node parallel processors) or services (animal care facilities, instrument specialists, technicians for common facilities and analytical labs) that are beyond the means of individual faculty members and that are purchased and/or maintained on a departmental basis.

This suggested a modified comparison conducted only on faculty who labeled themselves “experimental” or “both theoretical and experimental faculty” in the faculty survey. This comparison was conducted on 663 faculty and found that men who did experimental research reported a mean of 1,670 square feet of lab space, which was larger than the mean of 1,250 square feet reported by women who did experimental research. There are some interesting disciplinary differences. For example, in physics, men reported a median of 1,079 square feet of lab space and women report 800 square feet of lab space (see Appendix 4-12).

|

space each gender has.) Available at http://www.cyto.purdue.edu/facsurvey/faculty/survey/http://www.cyto.purdue.edu/facsurvey/faculty/survey/results/intro.htm. |

FIGURE 4-2 Mean lab space reported by respondents by gender and field.

NOTE: Rounded to the nearest 10 square feet.

SOURCE: Survey of Faculty carried out by the Committee on Gender Differences in Careers of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Faculty.

The committee’s survey also asked faculty who were hired after 1996 to report whether they had more, the same, or less lab space than they had when they were first hired. The analysis focused on comparing respondents who reported they had the same amount of lab space now compared to those who reported having more lab space now compared to when they were first hired. (Only 15 respondents noted that they had less lab space today.) A majority of both men and women reported no change in the size of their lab space (men, 72 percent; women, 70 percent). (See Appendix 4-13 for a multivariate treatment of this issue.)

Equipment

The survey asked respondents whether they had access to all the equipment they needed to perform their research. Three answers were coded: 2 = “Yes, I have everything I need,” 1 = “I have most of what I need,” and 0 = “I do not have access to major pieces of equipment that I need for my research.” We dichoto-

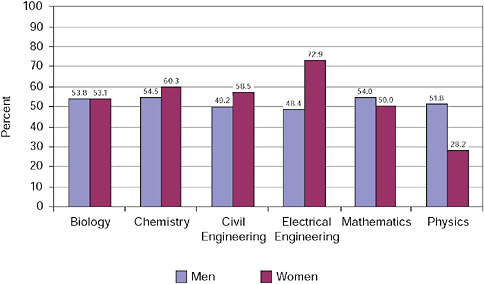

FIGURE 4-3 Percentage of men and women reporting having access to the equipment they need to conduct their research.

SOURCE: Survey of Faculty carried out by the Committee on Gender Differences in Careers of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Faculty.

mized the answers to examine faculty who had access to an acceptable amount of the equipment they needed compared to those who did not (a “1” or “0”). Of those who responded, men were more likely than women to indicate that they had access to sufficient equipment (95 compared to 91 percent), which was a difference that is approaching significance (see Appendix 4-14). Disaggregated by field (see Figure 4-3 and Appendix 4-14), men were more likely to report that they had all the equipment they needed in chemistry and marginally more likely to report that they had all the equipment they needed in physics. We wanted to compare these results to data from the NSOPF:04. Unfortunately, that survey questionnaire does not include questions on satisfaction with equipment. The 1993 survey did ask respondents to rate the quality of “basic research equipment/instruments,” “laboratory space and supplies,” and “availability of research assistants,” but those questions have been dropped from the more recent (1999, 2004) surveys.

Support Staff

The survey focused next on the number of research assistants (RAs) and postdocs supervised by the faculty, and the amount of available clerical support. For faculty, supervising RAs and postdocs is both an advantage and disadvantage. Such supervision may take a lot of faculty time and effort, yet support staff contributes a great deal to faculty research and publications, and thus, the avail-

ability of support staff can increase the productivity of faculty. Finally, supervising postdocs, who are the next generation of scholars, is recognized as one of the key activities of research faculty.

Faculty reported supervising between zero and 23 RAs, although 80 percent reported supervising between zero and 5 RAs. There was no difference between male (3.18 RAs supervised) and female (3.36 RAs supervised) faculty in the mean number of RAs supervised. Differences were small in every field.

Turning to postdocs, more than half of the faculty reported that they supervised no postdocs (see Appendix 4-15). The binary case (supervising no postdocs and supervising some postdocs) was then examined.20 In general, there was no difference between male and female faculty in the probability of faculty who reported supervising one or more postdocs. The field with the largest difference was in biology where 49 percent of the women compared to 62 percent of the men supervised postdocs.

Finally, we examined clerical support. Faculty were asked whether they had all of the clerical support they needed, some of the clerical support they needed, or no clerical support. The variable was collapsed to focus on those who reported that they were satisfied compared to those who had less than they wanted or no access. In general, 54 percent of men reported that they had all of the clerical support that they needed, compared to 40 percent of women (see Appendix 4-16). Examined by discipline (Figure 4-4 and Appendix 4-16), men were more likely to report that they had all of the clerical support that they needed in chemistry and civil engineering.

CLIMATE

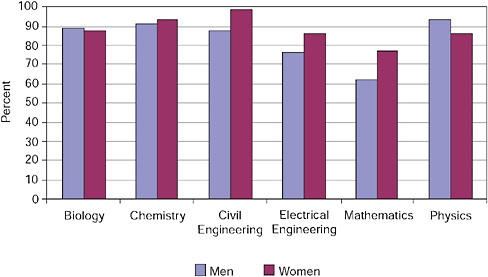

The Committee next examined some resources that may generally affect professional development. Here, the committee sought to assess whether male and female faculty were similarly engaged in their departments and institutions. There is a body of literature suggesting that women are isolated and marginalized. The former refers to not being part of the community in the department, institution, and more broadly (but not examined here), the scientific community. The latter refers to how much decision-making power women have on campus. In the wake of the 1999 MIT report, a number of universities conducted climate surveys on campus, discovering in some cases that female faculty face what is often termed a “chilly climate.” For example, a 2003 climate survey of assistant, associate, and full professors by the University of California, Berkeley, found that women did not feel very included (Figure 4-5).

To examine isolation, our faculty survey collected data on mentoring, collaborative research, and interaction with colleagues. To examine marginalization,

FIGURE 4-4 Percentage of faculty reporting having access to the clerical support they need, by gender and field.

SOURCE: Survey of Faculty carried out by the Committee on Gender Differences in Careers of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Faculty.

we asked about participation in several types of committees (see Appendixes 4-4 through 4-8). We compared the number of women in the department with the number of women on search committees for hiring, on tenure and promotion committees, and engaged in other forms of university service.

Mentoring

Mentoring is often described as having significant positive effects on the retention and advancement of faculty. The survey asked tenure-track faculty and faculty tenured after 2001 whether they had or have a faculty mentor at their current institution. Among tenure-track faculty, 49 percent of the men and 57 percent of the women reported having a faculty mentor—a difference approaching significance. Among recently tenured faculty, 45 percent of the men and 51 percent of the women reported having a faculty mentor, which was not statistically significant. Disaggregated by field with tenure-track and recently tenured faculty combined (Figure 4-6), women were more likely to report having a mentor in electrical engineering and physics (see Appendix 4-17). Mentoring appears to be becoming more popular, and mentoring programs are spreading to more universities.21 Thus, it is discouraging to find that only between half and two-thirds of

|

21 |

See for example, Center for Research on Learning and Teaching (CRLT), The University of Michigan, “Resources on Faculty Mentoring.” Available at http://www.crlt.umich.edu/publinks/facment.html. |

FIGURE 4-5 Inclusion in unit processes and culture by gender and discipline.

NOTE: Numbers at the end of bars represent sample sizes.

SOURCE: Angelica Stacy and Marc Goulden, UCB Faculty Climate Survey Report, 2003.

younger faculty have mentors in their home institutions. This does not seem to differ very much by discipline.

Collaborative Research

A second climate issue was whether the faculty member has been part of a research team at the institution. In this era of increasing collaboration and interdisciplinarity on campuses, it was expected that most faculty would report that they had been part of a research team, and indeed, 65 percent of women and 62 percent of men responded that they had. By field, more than half of the faculty in every discipline except mathematics reported that they had been part of a research team, with no substantial gender differences.

Faculty Interaction

The survey also examined how often respondents interacted with each other. The survey asked, “Over the past year, how many faculty members did you discuss ___________ with?” Respondents could answer: zero, one, two, three or more, or not applicable. The 10 topics were:

FIGURE 4-6 Percentage of faculty responding that they had a mentor by gender and field.

SOURCE: Faculty Survey carried out by the Committee on Gender Differences in the Careers of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Faculty.

Teaching

Research

Funding

Interaction with other faculty members

Interaction with administration

Climate in the department

Personal life

Family obligations

Salary

Benefits

We looked at whether there were significant gender differences for each issue separately. Men and women faculty did not differ in their reports of discussions with colleagues about 4 of the 10 issues (teaching, funding, interaction with administration, and personal life). Men reported significantly more discussion with colleagues about research, salary, and benefits than women. Men also reported marginally more conversation with colleagues about interaction with other faculty members and climate in the department. Only in the area of family obligations did women report marginally more conversations with colleagues than men reported.

Participation on Committees

Chairing committees was examined as one proxy for measuring marginalization—not having decision-making power within the department. As a first step, a variable was created to reflect the proportion of committees chaired by considering committees served on (i.e., the numerator is the number of committees chaired and the denominator is the number of committees served on, where the denominator is between zero and 9). Among the 1,063 faculty who served on at least one committee, 387 had chaired at least one committee. The variable was then dichotomized for faculty who participated on at least one committee into those who chaired at least one committee and those who chaired none of the committees on which they served. There was no significant difference between men and women in whether they chaired a committee on which they served (39 percent compared to 34 percent). An example of one of the committees reviewed is the chairing of undergraduate thesis committees. For this committee, there were disciplinary differences between male and female faculty in terms of chairing committees, with women chairing more committees than men in all fields except electrical engineering (see Appendix 4-5).

OUTCOMES

Professional activities, institutional resources, and climate can all be seen as inputs in the lives of faculty members. It is useful to know how faculty members spend their time, what resources are available to them, and how well integrated they are into the lives of their departments, universities, and disciplines. These factors are, however, only important to the extent that they contribute positively or negatively to a faculty member’s ability to perform at the highest level in his or her teaching and research. Each of these factors may contribute directly to a faculty member’s performance, or they may contribute to professional satisfaction and quality of life, which may in turn mediate between professional activities, institutional resources, and climate on the one hand and professional accomplishments on the other.

Teaching performance or effectiveness has been assessed in a variety of ways. The most prevalent is teaching evaluations (either by students or by peers), which are frequently used as performance indicators in salary, tenure, and promotion decisions (as well as for hiring decisions). Another possible approach that is interesting in principle but difficult in practice is the assessment of what students have learned in a course or while doing a project. One could also ask where a faculty member’s graduate students land postdocs, faculty positions, or other employment. Unfortunately, this information was not gathered as part of our survey, and there are no national studies on these outcomes, with the exception of a number of studies on student evaluations of teaching. Some of those studies have looked at whether there are gender differences in the evaluations male and female faculty receive

from students (Andersen and Miller, 1997; Centra and Gaubatz, 2000). However, a review of the literature suggests ambiguous results: “In many of these studies, male professors receive higher ratings than their female counterparts (Basow and Silberg, 1987; Kierstead et al., 1988; Sidanius and Crane, 1989). Others have female professors receiving higher evaluations than males (Tatro, 1995). Cashin’s (1995) review of the literature showed little to no difference. Feldman’s (1992, 1993) reviews found little to no difference in laboratory studies, while in observational studies, females had higher ratings in two-thirds of the cases” (Andersen and Miller, 1997:217). There could be a concern that women, who are particularly underrepresented in science and engineering, may be evaluated more harshly because they do not fit the perceived stereotypes of scientists or engineers.

In our survey, we asked about several important kinds of research performance or accomplishments. We asked respondents to tell us about their publications in the past 3 years, grant funding for their research, and how much lab space they had.

We also asked respondents to tell us about their salaries and whether they have been nominated for prizes or awards. Both salary and nominations for prizes or awards can be seen as indicators of the perceived quality of a faculty member’s teaching and research. Finally, we asked our respondents whether they had received an outside offer in the past 5 years. This can be seen as an indicator largely based on the faculty member’s research accomplishments.

We did not ask the respondents about their satisfaction with their professional lives. However, we do have data from the NSOPF:04, and we did ask our respondents whether they were thinking of leaving or retiring, which may be seen as an indirect measure of job satisfaction.

Research Productivity

Tenure and promotion often largely depend on research productivity, making it a crucial issue. Thus, the central question in this section: Is there a gender disparity in productivity? Faculty productivity can be defined in many ways. Here, we focus on grants received, lab space, and demonstrated, discrete output in the form of refereed publications and presentations.22 Some of these can be the result of the efforts of a single faculty member or a collaboration between faculty members. For example, journal articles are sole authored as well as co-authored. Different disciplines place different amounts of emphasis on individual versus joint efforts. In the analysis of our survey data, we have combined individual and collaborative outcomes. In addition, one can measure productivity over the career of a scholar or more recently. For example, the NSOPF approach is to ask survey respondents to consider their scholarly activity both recently (over the past 2 years) and over

their “entire career.” Previous studies have found in the past that female faculty evidenced less research productivity than male faculty; however, this gap appears to be shrinking over time (Cole and Zuckerman, 1984; Fox, 1983, 1985; Long, 1992; NAS, NAE, and IOM, 2007; Xie and Shaumann, 2003). This suggests focusing on recent publications and grant funding, and on current lab space, which is what we have done in our survey data.

Publications

The survey asked respondents to report on the number of articles they had published in refereed journals and in refereed conference proceedings during the 3 years prior to the survey. Data for sole authorship and co-authorship were combined into a single variable.

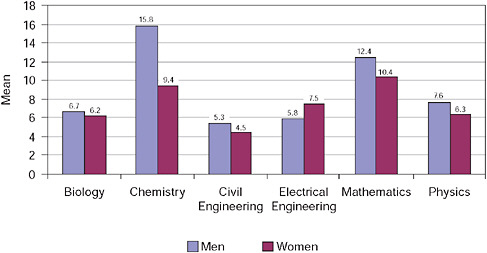

We looked first at journal articles published in refereed journals. Overall, male faculty published marginally more journal articles in the past 3 years than female faculty (men, 8.9 articles; women, 7.4 articles). It is important to note that these statistics and those that follow related to publications could be misleading, given the significant interactions discovered in our multivariate analysis of gender, discipline, publications, and other variables. Disaggregated by field (see Figure 4-7), men appear to publish more papers than women in chemistry (men, 15.8; women, 9.4). The differences between men and women in mathematics and physics were smaller, with women publishing more than men in electrical engineering.

We then looked at the total number of publications in refereed journals and conference proceedings combined. Overall, there appears to be no difference between male and female faculty in the total number of publications (men, 13.9; women, 12.8). Disaggregated by field, men published significantly more than women in chemistry, but not in any other field; women published marginally more in electrical engineering, but not in any other field.

There are two differences between our survey data and the data from the NSOPF:04. The first is that we only asked about articles in refereed journals and in refereed conference proceedings, while the NSOPF:04 asked about articles both in refereed and nonrefereed journals, as well as books, textbooks, reports, and presentations. The second is that we asked respondents to sum information over the previous 3 years, while the NSOPF:04 asked about the past 2 years. A summary of the NSOPF:04 data is shown in Table 4-1. In these data, male faculty had significantly more publications than female faculty in the previous 2 years (men, 10.9 publications; women, 8.2 publications). Looking at the gender differences in the various subcategories, however, we find that the only significant difference between men and women was in articles in nonrefereed journals, a category we did not include in our survey.

Both the faculty survey and the NSOPF use simple numerical counts as measures of publications. Counts are one sensible approach, but they have their problems. “Simple counts of articles and books published account for neither

FIGURE 4-7 Mean number of sole or co-authored articles in refereed journals by gender and discipline.

SOURCE: Faculty Survey carried out by the Committee on Gender Differences in Careers of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Faculty.

quality nor the importance of scholarship” (NSF, 2004b:8). Alternative approaches include weighting publications by the prestige of the source (e.g., top journals or university versus commercial presses for books) and counting citations of the publications to measure the impact of the faculty member’s research. Both of these approaches are very difficult, but as the debate over quantity is increasingly clarified, taking an approach such as one of these may be fruitful in the future.

Next, we asked which variables might contribute to the number of articles a faculty member published in refereed journals and conference proceedings in the past 3 years. (Again, given the interactions, this more conditional look is more likely to accurately reflect the nature of the impact of gender and discipline on number of publications. Specifically, because disciplinary area interacts with gender and number of publications, one cannot directly interpret the effect of discipline in isolation from gender, and gender in isolation from discipline.) First we looked at the number of refereed journal publications. This model was fit to 1,404 observations corresponding to full-time faculty, tenured or tenure-track. Only 934 (of the 1,404 faculty) had complete information on all covariates in the model and had reported a number of journal articles. The number of journal publications is a count variable, making a Poisson model plausible for this outcome variable. We found, however, that a normal distribution was also a plausible model because the number of journal publications varied between zero and 40 with a mean of about 9. Therefore, to facilitate interpretation of results, we fitted an ordinary linear model to the number of journal publications and included the

TABLE 4-1 Average Measures of Recent Research Productivity by Gender

following covariates: gender, discipline, faculty rank, type of institution (public or private), prestige of institution, percent of time spent in research activities, having or not having a mentor, and all of the two-way interactions between gender and the other factors. The R2 for the model was 19.0 percent (0.19).

Significant effects in the model were discipline (p-value < 0.0001), gender (p-value = .0001), rank (p-value < 0.0001), prestige (p-value = 0.0012), indicator for mentor (p-value = 0.005), percentage of time spent in research (p-value = 0.0001); and the three interactions gender with discipline (p-value = 0 .037), gender with rank (p-value = 0.042), and gender with mentor (p-value = 0.049).

Appendix 4-19 contains the least-squares (or marginal) mean number of journal publications for each level of each combination of fixed effects, and the lower and upper bounds of the 95 percent confidence intervals around each mean. Discipline has a very significant impact on the number of publications, as does gender, rank, prestige, and presence of a mentor. Also, discipline, rank, and presence of a mentor had modestly significant interactions with gender. Regarding the interaction of discipline and gender, we can assert that men publish more journal articles than women in biology; men publish more than women in chemistry; there is no significant difference between men and woman in mathematics, in electrical engineering, or in civil engineering; and men publish a borderline significant more than women in physics. Regarding the interaction of rank by gender, men increase the number of journal publications between the ranks of assistant and associated more than women do. The difference in the degree of increase from associate to full professor is less pronounced between the two genders. Regarding the interaction of mentor with gender, the difference between number of journal publications between men and women is more pronounced when faculty have mentors. Finally, the number of journal articles increases by 0.06 when a faculty member spends an additional 1 percent of his or her time in research activities.

The same analysis was then carried out in modeling total number of refereed publications (journal articles and refereed proceedings). Due to data quality

issues, this analysis was conducted on 1,019 faculty members who reported both their refereed journal publications and their refereed proceedings articles, and whose values were not unrealistically high. Of the 1,019, only 774 had complete covariate information. The least-squares regression model with the same covariates obtained an R2 of 23 percent. Since in this case no interactions were significant, it is easier to interpret the main effects. The significant effects were those of discipline (p-value < 0.00001), gender (p-value = 0.04), rank (p-value < 0.0001), prestige (p-value = 0.0002), mentor (p-value = 0.01), and percent time spent in research (p-value = 0.04). The marginal means and their 95 percent confidence intervals are provided in Appendix 4-19. Again, since none of the interactions among the main effects was significant, all the effects in this appendix can be interpreted in a straightforward manner. For instance, electrical engineers publish the most, followed by chemists, physicists, and civil engineers. Also, men publish more than women, and full professors publish more than associate professors, who in turn publish more than assistant professors. Furthermore, those at prestigious institutions publish more than those at less prestigious ones, and having a mentor increases the number of publications. Finally, since the regression coefficient of percent research time on fitting total number of refereed publications was 0.045 (with a p-value of 0.04), when research time increases by 1 percent, one can estimate that that will be accompanied by an increase in total publications of .045 per year.

Grants

In the sciences and engineering, grant activity is an important demonstrator of research ability. There are a number of approaches to comparing male and female faculty as grant recipients. Basic measures are whether faculty have received any grants and the total dollar value of any grants received. More in-depth measures include whether the grantee is a principal investigator (PI) or co-principal investigator (Co-PI), the source of grants, and the type of grants.

NSOPF:04 asked respondents whether any of their scholarly activity was funded. One hundred percent of both male and female full-time, professoriate faculty in S&E at Research I institutions indicated that it was. Our faculty survey found a lower percentage of faculty who responded that they were receiving sponsored research grants. It asked respondents, “What is the total dollar amount of the research grants on which you served as principal investigator or co-principal investigator during the 2004-2005 academic year? Include only direct costs for academic year 2004-2005.” There were 213 faculty out of a total of 1,404 full-time faculty who did not provide an answer to the question. Of the 1,191 respondents, 163 (14 percent) answered zero, which means 86 percent of respondents (and 73 percent of all full-time faculty) reported some grant funding. This lower percentage found in our faculty survey compared to the NSOPF:04 is probably due to the fact that we asked faculty to limit their response to grants on which

they served as a PI or Co-PI. Further, not all faculty may have interpreted the question in the same way; it may be that some among those reporting no funding had research funding during 2004 to 2005 but did not receive any new funding. A similar proportion of men and women (16 percent and 14 percent, respectively) had missing grant information. Thus, we base the remainder of the discussion on those faculty members who reported either no grant funding or some grant funding in the survey.

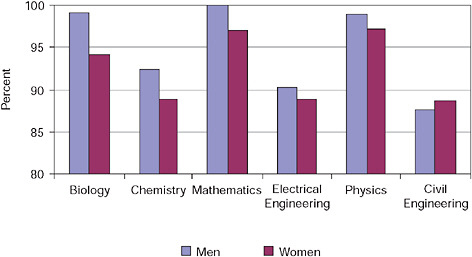

Women were more likely than men to report that they had grant income (88.6 percent compared to 83.8 percent). The University of Pennsylvania gender equity report found that women and men were equally likely to obtain grant support. As shown in Figure 4-8, disaggregated by field, women and men were equally likely to have at least one research grant on which they served as a PI or Co-PI, except in civil engineering (women, 99 percent; men, 88 percent) and mathematics (women, 77 percent; men, 62 percent), in which the differences were significant.

However, there may be differences when grants are examined in more depth. Although the University of Pennsylvania gender equity report found that men and women were equally likely to obtain grant support, it also found that men were more likely to be PIs, which suggests that an important focus for research would be which faculty have been PIs and which have been Co-PIs. Second, men and women may not be receiving the same types of grants. For example, while women’s participation in National Institutes of Health grants is growing, the percentage is still quite small, and in some categories, the size of awards of the same type are smaller for women than for men (OER, 2005). However, a recent study by RAND (Hosek et al., 2005) found no gender differences in the amount of funding requested or awarded during the period 2001 to 2003 at National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Interestingly, the study also found “gender differences in the fraction of first-year applicants who submit another proposal in the following two years” (p. xii). Women were less likely to reapply.

The next question in the faculty survey focused on the size of the grants received by the faculty member. About 6 percent of respondents answered that they had received $1 million or more in grant funding. The median response was $160,000.23

To explore the association between individual and institution-level factors and the success with which faculty raise research funding, we proceeded in two steps. We first modeled the binary outcome “grants/no grants” using logistic regression as a function of the following covariates: (1) gender, (2) disciplinary area (e.g., biology), (3) faculty rank (assistant, associate, or full), (4) type of institution (e.g., public versus private), (5) prestige of the institution, (6) number of publications,

FIGURE 4-8 Percentage of faculty reporting having at least one research grant on which they served as a PI or Co-PI by gender and field.

SOURCE: Faculty Survey carried out by the Committee on Gender Differences.

(7) percent of time spent on research, (8) whether the faculty member reported that he or she had a mentor or not, and (9) all two-way interactions between the above covariates (see Appendix 4-20a and 4-20b for the analysis). This provided an estimate of the chance that a faculty member would or would not receive a research grant, regardless of the size. It is important to mention that whether a faculty member was or was not awarded a grant is of interest in itself because in some disciplines, receiving funding from a competitive agency is at least as important as the actual amount of funding received.

In a second modeling step, we estimated the amount of funding received conditional on having at least some research funding. The dependent variable was not the amount of grant funding, but instead the logarithm of the amount of grant funding to provide a dependent variable with a less skewed distribution, which can be useful in such models. There were 799 faculty (out of 1,191 who responded to the question about grants) with complete information for all model covariates. Of these, 697 (87 percent) reported receiving some grant funding during the period of interest.

We cannot conclude whether gender is associated with the probability of having a grant because the interaction between gender and discipline and between gender and rank were both statistically significant (p < 0.05). Women were significantly more likely (p < 0.05) to report having some grant funding in mathematics and in civil engineering, but the differences between the two

genders were not significant in the other disciplines. Female full professors were significantly more likely to report some grant funding than their colleagues at the associate and assistant professor ranks, but for men, the gender rank interaction term was significant (see Appendix 4-20a and 4-20b). Overall discipline was significantly associated with the probability of having a grant, with faculty in electrical engineering being less likely (p < 0.05) to have a grant than faculty in the other disciplines. Faculty in civil engineering were significantly more likely (p < 0.001) than faculty in other disciplines to report some grant funding. The effect of discipline, however, is impossible to isolate, since the interaction between discipline and gender is highly significant, even after accounting for confounders such as rank, type of institution, and others. Assistant professors were less likely than associate professors (p = 0.007) and full professors (p < 0.0001) to have a grant, but there was no significant difference between full and associate professors. Again, discussing the effect of rank independently of gender is not reasonable, given the significant interaction between the two factors. Faculty at private institutions were equally likely to have a grant than those at public institutions (p > 0.05), and faculty at institutions of lower prestige were only marginally less likely (p = 0.06) to have a grant than faculty at institutions of either medium or higher prestige (which did not differ from one another). The number of publications a faculty member had was not associated (p = 0.9) with the probability of having a grant. Faculty who spent a greater percentage of their time on research were more likely to have a grant (p < 0.01). Finally, a faculty member who had a mentor appeared at first glance to be less likely to have a grant than a faculty member who did not have a mentor (p < 0.0001). However, this effect is difficult to interpret because the beneficial effect of the mentor depended on the gender of the faculty being mentored (p < 0.03). In fact, and contrary to what we might have anticipated, survey results suggest that the effect of having a mentor is not statistically significant among men. However, among women, a strong association between having a mentor and having grant funding was demonstrated.

Regarding the data on the interplay of gender and the availability of a mentor, we find in Table 4-2 that female assistant professors who do not have a mentor have a substantially lower probability of having a grant than female assistant professors who do have a mentor.24 For male assistant professors, the presence of a mentor seems to make little difference. For associate professors, the presence of a mentor is associated with an increase in the probability of receiving a grant for both men and women, but the effect is much less pronounced than for female assistant professors.

We now consider the size of the grant and model the amount of funding as

TABLE 4-2 Percentage of People Who Received Grant Funding by Gender, Rank of Faculty, and Mentor Status

|

Gender |

Assistant |

Associate |

|

Males with mentor |

.83 |

.93 |

|

Males with no mentor |

.86 |

.86 |

|

Females with mentor |

.93 |

.98 |

|

Females with no mentor |

.68 |

.87 |

|

SOURCE: Survey of faculty carried out by the Committee on Gender Differences in Careers of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Faculty. |

||

a function of the same covariates. We used a log transformation on the response variable to better meet the normality assumption in the linear model. Because the log transformation collapses at zero, we added a negligibly small amount ($10) to the funding reports of zero. Figure 4-9 shows the distribution of funding amounts for all disciplines (except mathematics) in the log scale. Note that the distribution has a point mass at 2.3, which corresponds to the log of 10—the small amount added to grants of zero.

To explore the association between gender and other covariates on size of the grant, we considered all observations but fitted a Tobit regression model where the truncation bound was set to 3.0 (since the log of 10 is 2.30). That is, we obtained estimates of regression coefficients in the model that are unbiased and consistent once we account for the truncation. Of the observations, 485 exceeded the lower truncation bound and 221 did not.

There was no difference in the amount of grant funding received by male and female faculty after accounting for possible confounders of discipline, rank, type of institution, prestige of the institution, and research productivity (as measured by the number of publications).

Faculty in mathematics received grants of significantly smaller size (p < 0.001) than faculty in all other disciplines. Mathematics aside, the differences among all other disciplines were not statistically significant, with the exception of biology. Full professors had significantly larger grants than associate professors (p < 0.0001), who in turn had significantly larger grants than assistant professors (p < 0.003). Faculty at universities of highest prestige had significantly more grant funding (p-value = 0.002) than faculty at institutions of lower prestige, but the difference between the size of the grants received by faculty at the highest and the medium-prestige institutions was not significantly different (p = 0.12). Faculty at institutions of medium prestige had, in turn, marginally more funding than faculty at institutions of lower prestige (p = 0.07). These results are supported by the following average grant sizes: The average size of a grant obtained by faculty in 2004-2005 was $336,257, $352,639 and $463,231, respectively, at institutions of lowest, medium, and highest prestige. These values must be interpreted with caution. Making sweeping inferences

about funding levels across institutions, ranks, or even gender is unwarranted, given that we are considering only 1 year of funding data. Neither the number of publications nor the percent of time spent on research activities were associated with the size of grants obtained by faculty (p = 0.3 and p = 0.7, respectively); faculty with a mentor had less funding than faculty without a mentor (p = 0.01), which may reflect the fact that mentors are more prevalent among younger faculty who in turn tend to receive the smaller grants.

It is also of interest to investigate the association between gender and covariates conditional on funding. That is, if we were to consider only those faculty members who reported receiving some funding during 2004 to 2005, would results differ from those obtained when analyzing the entire set of outcomes? We anticipated that gender would not be associated with the amount of funding received by a faculty member even in the conditional analysis, given that gender was not found to be a predictor of the probability of receiving a grant or of the amount of grant funding unconditionally. A multivariate normal regression model fitted to the log-transformed positive grant values leads to approximately the same conclusions as the analysis that considers both zero and positive values together. Gender was still not associated with the amount of funding received, given that at least some funding was received. Full professors received significantly more funding than associates, who in turn received more funding than assistant professors. As before, the prestige of the university was positively associated with the amount of funding; the higher the prestige, the higher the average size of grants, everything else being equal. As before, we found that discipline was significantly associated with grant size, but essentially all of this effect is due to the fact that faculty in mathematics received significantly smaller grants than those in the other five disciplines.

Laboratory Space

We have already considered laboratory space as an institutional resource, because it is so crucial to the ability of faculty to get their research done. In our survey, male faculty reported having significantly more lab space than female faculty. This holds true both when we consider all faculty taken together and when we consider only those faculty who do experimental research. Here we look at what factors might contribute to the amount of lab space that a faculty member has and to the gender disparity in lab space.

Figure 4-10 shows the distribution of lab space in the entire sample (except mathematics) in the log scale. When space was reported as “0,” a negligible amount (10 square feet) was added to allow for the transformation. Note that after the log transformation, lab space has a distribution that is approximately symmetric. Thus, a linear model was fitted to the log of lab space.

Explanatory variables in the model were gender, discipline, faculty rank, type of institution (public or private), prestige of the institution, grant funding, publi-

cations (refereed journal articles and conference proceedings), type of research (experimental, theoretical, both, educational, other), academic age (defined as time elapsed between receipt of Ph.D. and December 2004), and all two-way interactions with gender. Gender, discipline, rank, institution type, and prestige were classification variables; other variables were included as continuous. A random effect for institution was included, but the institution variance component was negligibly small. Because none of the interactions between gender and the other covariates were significantly different from zero, the model was re-fitted, but included only main effects. The model fitted the data reasonably well (R2 = .32).

Significant associations with lab space were found for discipline (p < 0.0001), rank (p < 0.0001), type of institution (p < 0.05), prestige (p < 0.01), grant funding (p < 0.0001), research type (p < 0.0001), and publications (p = 0.012). Importantly, gender was not associated with lab space. Since, overall, when other variables were not taken into account, male faculty had significantly more lab space than female faculty, the absence of a significant gender difference in this analysis suggests that the overall difference is a function of gender differences in one or more of the other variables in the analysis. The most likely candidates were discipline and rank. We know that the percentage of female faculty varies between disciplines and between ranks. Therefore, if the disciplines and ranks with more male faculty were also the disciplines and ranks with more lab space, a simple comparison of the lab space of male and female faculty would show an overall advantage for men.

There are several interesting effects of variables on lab space. First, there was a positive association between grants and lab space. Everything else being equal, a faculty member who doubles his or her funding in a year can expect an 11 percent increase in lab space. Therefore, the effect of increased funding on space depends on the level of funding. A faculty member who has $10,000 in sponsored funding would only need to raise about $20,000 to increase his or her space by 11 percent. Yet someone who already has $100,000 would need to reach $200,000 in funding to have the same effect on his or her space. Second, not surprisingly, experimental researchers (most faculty call themselves experimental, and therefore research type was dichotomized to experimental or nonexperimental—and most women declared themselves to be experimental) reported having more lab space. Third, faculty at public institutions received more lab space than faculty at private institutions. Fourth, faculty at the most prestigious institutions reported having more lab space than faculty at institutions of medium prestige, who in turn report having more lab space than faculty at the least prestigious institutions. Fifth, our study indicated that the more senior faculty (those who have moved up in rank) had more lab space. This, however, is not a conclusion well supported by our data, which by their cross-sectional nature do not permit drawing longitudinal inferences. A snapshot impression can be misleading if, for example, senior faculty with large labs at a given point in time also had large labs when they were junior faculty. The effect of increase in rank and the effect of time itself are confounded when we

can only explore faculty with a range of rank but during a single period of time. Finally, every additional publication, all else being equal, was associated with an increase in lab space of about 1 percent.

Nominations for Honors and Awards

Recognition in the field can be seen as another indicator of productivity, broadly defined, and as a goal that can bring greater job satisfaction, and perhaps indirectly affect such outcomes as likelihood of receiving a grant. One recent report examining the percentage of women nominated to an honorific society or for a prestigious award, and the percentage of women nominees elected or awarded from 1996 to 2005, found the percentages to be quite low (NAS, NAE, and IOM, 2007:128).

We asked respondents whether they had been nominated by their current department or institution for any international or national prizes or awards. Appendix 4-22 gives the number of faculty in each discipline who reported being nominated for at least one award at their current institution, as well as the number of missing responses in each discipline, by gender group. Overall, there was no gender difference in rate of nomination, with 28 percent of men and 26 percent of women reporting that they had been nominated. There were differences across gender when the data were disaggregated into the six disciplines we surveyed. Women were more likely to be nominated than men in electrical engineering and in civil engineering, and men were more likely to be nominated than women in biology and mathematics. Future research should also ask about nominations for university prizes or awards, and should ask separately about awards for research and those for teaching.

We looked at whether the probability that a faculty member would be nominated for an international or national prize or award was associated with various institutional or individual variables. There were 796 faculty with information for nominations and about all covariates in the model, and 240 of these reported having been nominated for an award. The probability that a faculty member would be nominated for an award was significantly associated with discipline, prestige of the institution, and type of institution. With one exception, none of the interactions between gender and any of the other variables was significantly related to the probability of being nominated for a prize or award. The exception was the interaction between gender and discipline, which was statistically significant (p < 0.01). This significant interaction prevents us from discussing the effect of discipline in isolation.

The probability that a faculty member would be nominated for an award was higher at private than at public institutions (p = 0.03). At institutions of high or medium prestige, faculty were either 1.5 or 5.5 times more likely, respectively, to be nominated for awards than at institutions of lower prestige. Not surprisingly,

faculty with more refereed publications were more likely to be nominated for a prize or award than faculty with fewer, but this difference was not substantial.

Salary