Diagnostic Assessment and Countermeasure Selection: A Toolbox for Traffic Safety Practitioners (2024)

Chapter: 2 What Causes Roadway Crashes?

CHAPTER 2

What Causes Roadway Crashes?

2.1 Objectives

The objectives of this tool are to

- Summarize research into the contributing factors to roadway crashes,

- Present basic human factors concepts and describe how they relate to driving, and

- Describe the four key human factors contributors to crashes.

2.2 Background

Successful safety management practices—including the selection of properly focused and cost-effective countermeasures—depend on an accurate understanding of the underlying contributing causes of crashes. To aid both diagnostics and design activities, researchers have been exploring ways to approach and model accidents (including roadway crashes) for many years (for a useful summary, see Coury et al., 2010).

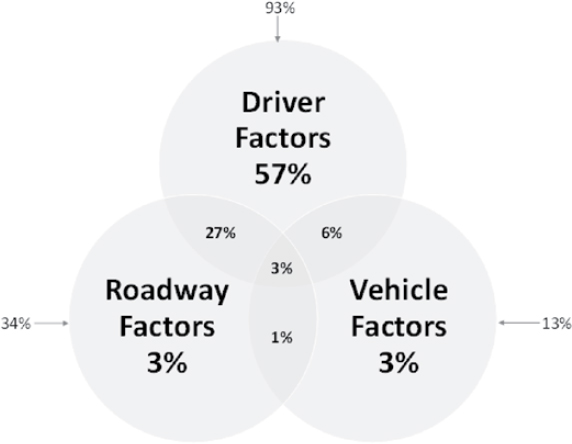

Summary of research into crash causality. Building on this earlier work that focused on industrial accidents, plane crashes, railroad derailments, and nuclear power incidents, more recent research studies and governmental investigations have applied these general approaches to roadway crash causation, in which they fostered ideas about how to prevent crashes from occurring and about implementing countermeasures. For example, in 1979, Treat and colleagues published a seminal report for the United States Department of Transportation (U.S. DOT) that showed in an analysis of over 2,000 motor vehicle crashes that nearly 93% were caused in some part by human factors; more specifically, they identified improper lookout, excessive speed, and inattention as the top reasons for crashes because of human factors issues (Treat et al., 1979). Figure 5 summarizes the results.

Other probable causes for crashes included environmental factors such as view obstructions and slick roads, as well as vehicular factors such as brake failure and tire underinflation. Treat et al. (1979) suggested several countermeasures that are still relevant today, substantiating the notion that most of these crashes are indeed caused by human factors-related issues rather than vehicular or environmental factors that would otherwise be solved with advances in automotive technology or improved infrastructure.

In 2008, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) conducted the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey (NMVCCS), in which 6,950 crashes from 2005 to 2007 were evaluated (NHTSA, 2008a; Singh, 2015). The results acquired from this survey allowed for identifying common pre-crash events and scenarios, such as turning or crossing at intersections, and for determining critical reasons underlying these events, which include driver errors, vehicle and environmental conditions, and roadway design. The National Transportation

Safety Board (NTSB) has also helped clarify the contributing factors of crashes by generating detailed investigative reports of numerous transportation crashes, which identify major safety issues and assess the efficacy of traffic control measures in protecting pedestrians and vehicles from crashes (NTSB, 2004; NTSB, 2009). These investigative reports have resulted in recommendations for improving roadway safety and preventing crashes.

Most recently, Dong and Wood (2023) assessed the contributing factors to crashes using 2017–2020 data from the Crash Investigation Sampling System (CISS) (NHTSA, n.d.b) and 2010–2015 data from the National Automotive Sampling System (NASS) Crashworthiness Data System (NHTSA, n.d.d) using taxonomies that included those used by Treat et al. (1979) and Singh (2015) (i.e., human factors, vehicle factors, and roadway and environmental factors). These data sets are very detailed and include police-reported crash information, crash reconstructions, hospital data, and interviews of people involved in the collisions. The findings were overall very similar to those reported previously; more than 95% of the crashes investigated involved human factors or included a human error.

Nature and types of driver errors. The concept that humans play a fundamental role in roadway crashes has been utilized to develop taxonomies to better understand and assess the driver errors that lead to crashes. To elaborate, in the 1990s, James Reason detailed how the psychological nature of humans contributes to accident causation by categorizing the types of errors that they commit into two groups: (1) slips (i.e., unplanned actions), lapses (i.e., covert memory failures) and mistakes (i.e., planning or problem-solving failures); and (2) violations (i.e., motivational problems) (Reason, 1995). Reason began developing such distinctions between categories by having individuals complete a driver behavior questionnaire, which asked them to judge the frequency with which they committed various types of errors and violations when driving (Reason et al., 1990). From these results, Reason identified three factors: violations, dangerous errors, and relatively harmless lapses. These survey results emphasized the view that different psychological mechanisms mediate errors and violations when driving. For example, individuals who reported having the most violations tended to rate themselves as skillful drivers, errors and lapses when driving involved cognitive competence (e.g., attentional) failures, and violations involved the motivational factors of the driver (Reason et al., 1990). Taken together, these

findings highlight the importance of considering the driver’s psychological state when assessing the errors and violations involved in crash causation.

Driver error categorization has been used as a methodology by others to create more specific categories in the formation of diagnostic tools, such as checklists and questionnaires, that may be used for assessing the causes of roadway crashes. Wierwille et al. (2002) collected data from focus groups with police officers and interviews with drivers involved in crashes to develop a novel taxonomy to describe driver errors, which included topics such as inadequate knowledge, training, and skill; impairment; willful inappropriate behavior; and infrastructure or environment problems (Wierwille et al., 2002). These topics highlighted the need to consider not only willful violations but also how drivers interact with the surrounding infrastructure features; this concept is exemplified by organizing the driver-related issues into a tree diagram that branches off into other contributing psychology- and infrastructure-related components (Wierwille et al., 2002). For example, failure to yield at an intersection may be the general category that describes the crash type, but that kind of driver error may branch off into more particular components, like the type of intersection (infrastructure-related) and specific reasons for not yielding (related to human factors) (Wierwille et al., 2002).

Most crashes reflect multiple contributing causal factors. Crashes are complex, and multiple converging elements are associated with many roadway crashes. Thus, an effective framework and methodology for the diagnostic assessment of crashes should include not just a review and analysis of relevant road user, environmental, and vehicle factors but also the interactions between these factors. This perspective is emphasized by the crash trifecta concept, which includes unsafe pre-incident behavior or maneuvers; transient driver inattention; and unexpected traffic events. The first element of the crash trifecta, unsafe pre-incident behavior or maneuvers, includes actions that are typically under the driver’s control and may occur before the safety-critical event. Examples of this element include speeding, tailgating, and making an unsafe turn (Dunn et al., 2014). The second element is transient driver inattention, which may or may not be related to the act of driving. For instance, a driver may be suddenly distracted when checking mirrors to determine whether or not they could safely move to the adjacent lane.

However, the driver may also become transiently distracted if their mobile phone falls on the car floor and they reach to retrieve it, which is not linked to the act of driving itself (Dunn et al., 2014). The final element of the crash trifecta includes an unexpected traffic event, which refers to an unexpected action or random event committed by another vehicle or obstacle, such as a deer suddenly running out in front of the vehicle (Dunn et al., 2014). Taken together, these three elements make clear that factors contributing to many vehicle crashes involve an interaction between driver-related and non-driver-related factors and events.

Looking at the role of interactions between contributing factors is not a new perspective on crashes; the Haddon Matrix (Haddon, 1972; Haddon, 1980) has long provided a technique and tool for looking at factors related to personal attributes, vehicle attributes, and environmental attributes before, during, and after an injury or death. Human factors evaluations of crashes have similar goals: to conduct site-specific human factors evaluations and to consider and list the individual road user, vehicle, and environment factors (plus interactions) that could contribute to driver confusion, misperceptions, high workload, or other mistakes and errors. In this regard, Campbell et al. (2018) proposed using the Human Factors Interaction Matrix (HFIM) to specifically identify road users and other factors that could contribute to driver errors across a range of various scenarios and driving situations.

Critically then, it is often the interactions among road users, vehicles, and the environment that lead to errors, conflicts, crashes, and fatalities. Errors made by road users do not generally reflect the breakdown or occurrence of a single factor; they reflect a confluence of factors that occur more or less simultaneously. For example, a crash does not generally happen just because a driver is older; rather, it might happen to an older driver driving at night, under bad weather

conditions, when faced with a sign that may be wordy, complicated, damaged, or worn out. This emphasis on the role of interactions in crashes is well-supported by crash-data research such as that reported by Treat et al. (1979) and Singh (2015).

2.3 Key Concepts: Contributing Factors to Roadway Crashes

Human factors refer to the role of user capabilities and limitations in crashes. As shown in Figure 5, while most crashes reflect some sort of driver error, some of these errors (approximately 57%) reflect driver behavior issues, such as impaired driving because of drugs or alcohol, road rage, fatigue, and distraction/inattention, while others (approximately 30%) reflect human factors issues, that is, roadway designs and traffic operation features that unknowingly place demands on road users that may exceed their capabilities. Chapter 3 describes the distinctions between these types of contributing factors and provides some diagnostic questions that will aid the practitioner in discerning between them. The chapter briefly introduces human factors and identifies the key ways in which roadway designs and traffic operation features can place demands on road users that may exceed their capabilities.

The study of human factors applies knowledge from human sciences such as psychology, physiology, sociology, and kinesiology to the design of systems, tasks, and environments to promote and support safe and effective use. The goal of understanding the effects of human factors is to reduce the probability and consequences of human error—especially the injuries and fatalities resulting from these errors—by designing systems, tasks, and environments that consider inherent, relatively stable human capabilities and limitations.

These human capabilities and limitations are relevant to roadway design, driver performance, and the general safety performance of a roadway. The roadway system reflects complex interactions between different road users (e.g., drivers, pedestrians, and bicyclists), vehicle types (e.g., cars, motorcycles, trucks, and trains), and elements in the environment (e.g., roadways, markings, signs, and weather conditions). The design of the roadway system impacts numerous safety-relevant behaviors on the part of drivers, such as where they are looking as they drive, how they maintain their lane position, and how they select their speed. These behaviors have been studied by human factors researchers and practitioners for many years. Drivers make frequent mistakes because of their physical, perceptual, and cognitive limitations; some of these mistakes may lead to conflicts between road users or even near misses, but others may lead to crashes that result in injuries or deaths.

What are these capabilities and limitations, and how do they relate to driving, a pedestrian trying to cross a street, or a bicyclist sharing the roadway with vehicles? Capabilities and limitations may be summarized by reference to a human information processing model, which is a frequent and convenient way to represent how humans relate to their environment (Wickens, 1992). In a nutshell, as a road user directs their attention to the environment, their senses receive and process raw information (i.e., they see, hear, and feel); they interpret and organize this information into more concrete perceptions; they store that information in memory and then use that information (along with other information they have stored in the past) to make decisions and execute responses.

While a thorough review of the human information processing model is beyond the scope of this chapter, suffice it to say that these processes—seeing, perceiving, remembering, deciding, and responding—have elements and constraints that reflect the inherent physical and mental abilities of all road users. For example,

- Seeing requires having sufficient light and visual contrast between an object and its background;

- Perceiving involves an awareness of the elements within the environment, such as the speed and distance of approaching vehicles;

- Remembering includes memory of traffic rules or of the meanings of signs passed;

- Deciding involves knowledge, mental ability; and

- Responding requires physical ability and time.

These information-processing elements translate into roadway design principles that will support accurate and timely behaviors from drivers and other road users. While there are differences in these capabilities and limitations across individuals (e.g., older versus younger drivers), proficiency (e.g., experienced versus inexperienced drivers), and circumstances (distracted versus unimpaired driving), they vary within relatively restricted and well-known boundaries. For example, vision is the primary source for obtaining information while operating a motor vehicle, and researchers have estimated that as much as 90% of the information needed for the driving task is obtained through vision, highlighting the importance of treating roadways as an information system (Dewar and Olson, 2007). Roadways are always sending messages to the road user. The roadway designer should aim to design the road in such a way that the right messages are being sent at the right time.

Driving example: responding to an advance warning sign. Consider the information processing elements and the roadway as an information system in the context of a simple and common driving activity such as slowing a car in response to a sharp curve in the road. See the example in the text box.

Suppose a driver is approaching a curve in the roadway and sees a roadway sign just ahead of the curve that provides an advance warning (“Curve Ahead” sign) of the approaching curve. The driver sees the sign, processes the words on the sign (including other cues such as sign color, shape, and location), and then recognizes the sign given the driving context. The driver processes the curve itself as well and, based on features such as lane width, radius, and current speed, re-assesses the current vehicle speed. From the driver’s perception of current speed and memory about the sign’s meaning given the driving context, the driver determines that the sign means it is necessary to slow down. The driver decides to slow down, and then lets off on the accelerator and steps on the brake in such a way as to slow down at the right location to support positioning within the curve that is efficient and keeps the vehicle within the lane boundaries.

Table 4 integrates the description of human information processing elements with this simple task of slowing a car in response to a sharp curve in the road; consider how different roadway elements combine to communicate with and provide messages to the driver. In the table, the sensation, perception, and attention elements might be characterized as the active information-seeking portions of driving; the decision-making element is where the driver determines what to do; and the response execution element includes the physical acts involved in making steering, accelerator, and brake inputs to the vehicle. However, the elements do not necessarily occur in a fixed sequence, and under most circumstances, they reflect a series of stages with multiple feedback loops and no fixed starting point.

Human factors are important to highway safety because human factors issues related to the infrastructure can contribute to driver errors, and such errors can—in turn—contribute to crashes. Many crashes occur when the demands of the roadway environment exceed the capabilities of the roadway user. For example, the roadway can include objects that you cannot see because of limitations in your visual abilities (e.g., a dark-clad pedestrian at night), or it can require you

Table 4. Application of the information processing model of human capabilities to a simple driving task.

| Human Information Processing Element | Description | Application of the Curve Ahead Sign to What the Driver Does |

|---|---|---|

| Attention | Actively processing information—can occur unconsciously or under active control | Focusing awareness on the critical aspects of the roadway environment |

| Sensation | Seeing, hearing, feeling | Sensing specific features of the environment—the roadway, lane width and edges, and the Curve Ahead sign |

| Perception | Organizing and interpreting senses into a coherent “picture” through a series of top-down (context, whole scene) and bottom-up (individual elements) processes | Extracting meaning from the scene by using aspects of the environment such as color and luminance gradients, separations between the roadway itself and scene elements on the roadway, and the relative location of these scene elements |

| Decision-making | Selecting between response options | What to do? Deciding to slow down and to adjust steering |

| Response Execution | Acting, doing | Releasing the accelerator, pressing the brake in a controlled manner, and matching steering inputs to road curvature |

| Memory | Retaining and recalling | Supporting the entire task by providing meaning to the sign, based on knowledge and past experience with this stretch of roadway |

to respond to changing conditions faster than you can perceive and respond to these conditions (e.g., an off-ramp that is too close to a decision point).

Even crashes associated with impaired driving fit this “demands versus capabilities” framework, as impaired driving (e.g., driving while drunk or under the influence of drugs, distracted driving, fatigued driving) can reduce baseline capabilities related to information processing elements such as vision, perception, decision-making, and response times. For example, distracted driving may reduce the time available to perceive and extract important information from the roadway environment, drugs may impair decision-making abilities, and alcohol may slow response times to roadway hazards. Thus, understanding inherent human capabilities and limitations and how roadway infrastructure can be misaligned with them will aid practitioners in diagnosing crashes and in identifying and balancing trade-off decisions among countermeasures.

2.3.1 Human Factors and the Demands of the Driving Task

While the tools for diagnostic assessment summarized in Chapter 1 include behavioral elements (i.e., road users’ responses to the roadway environment), they can lack insights to help clarify the relationships between roadway design and operations decisions, crash frequency and severity outcomes, and the underlying needs and characteristics of road users. In keeping with the role that user errors and mistakes play in roadway crashes (Treat et al., 1979; Wierwille et al., 2002; Singh, 2015), the tools provided in this toolbox incorporate and refer to human factors topics (i.e., interactions between the road user and the infrastructure) and address roadway design from an engineering standpoint.

When task demands exceed user capabilities, crashes are more likely. The discussions in several sections of this chapter focus on the important role that demands play in road user performance and—in general—the safety performance of a roadway. Indeed, understanding how drivers interact with the roadway allows highway agencies to plan and construct highways in a manner that minimizes human error and its resultant crashes. A key premise of this toolbox is that human factors are important to highway safety because human factors issues related to the infrastructure can contribute to driver errors, and such errors contribute to crashes. In short, many crashes happen when the demands of the roadway environment exceed the capabilities of the roadway user.

Driving involves a complex series of physical actions and mental operations that vary considerably across driving contexts, situations, and conditions. For example, there are differences in the demands and effort associated with merging onto a busy urban freeway at night compared to driving a long section of freeway with light traffic in the middle of the day. Another approach is to link specific features of the driving environment with the information processing elements through a more detailed task analysis of driver activities and associated demands. Task analysis is a technique that can be used to describe any goal-oriented set of human activities. It typically includes the successive decomposition of a high-level activity into smaller elements (e.g., segments, tasks, and subtasks) with specific information processing elements and workload estimates developed at the subtask level. The technique is highly flexible in terms of how information may be generated (e.g., through observations, interviews, or expert analysis) and how task details are presented (e.g., from the simple text presented in tabular form to complex graphical depictions).

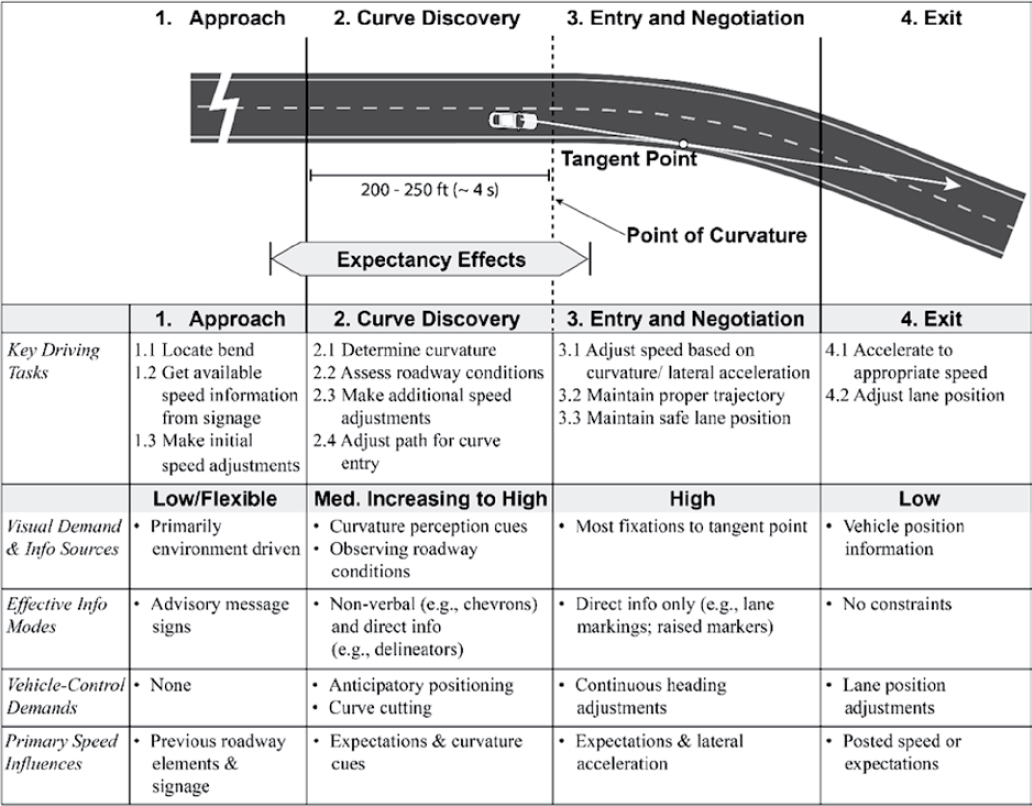

The driver demands associated with navigating a curve were illustrated in a task analysis included in the Human Factors Guidelines for Road Systems (HFG) (Campbell et al., 2012) and can serve as an example of how analyzing driver tasks can be helpful for understanding how roadway design impacts driver performance. Figure 6 describes the activities that drivers would typically perform while navigating a single horizontal curve. From this example, it is evident that certain tasks—like maintaining speed and lane position while entering and following the curve—are more demanding and challenge the driver to pay closer attention to basic vehicle control and visual information acquisition. Also, since the task analysis identifies the key information and vehicle control elements in different parts of the curve driving task, Figure 6 illustrates how and when driver demands are influenced by design aspects such as design consistency, degree of curvature, and lane width. In particular, identifying highly demanding (or high-workload) components of the curve driving task indicates where drivers might benefit from information regarding delineation or benefit from the elimination of potential visual distractions. The concept of driver demands and workload is discussed in more detail in Chapters 8 and 11.

2.3.2 Key Human Factors Issues Associated with Crashes

Human factors issues as contributors to roadway crashes have been the subject of empirical studies for decades, with many such studies summarized in the HFG (Campbell et al., 2012). These studies have identified several human factors issues that are frequently linked to crashes. For example, the recent Primer on the Joint Use of the Highway Safety Manual (HSM) and the Human Factors Guidelines (HFG) for Road Systems (Campbell et al., 2018) identified several candidate human factors issues, including age, visual capabilities, driving experience, cognitive ability, language/culture, road familiarity, physical abilities, attitudes, and training (in addition to driver behavior issues). Though this set of candidate issues provides a good foundation for understanding of the role of human factors issues in crashes, it is too broad and lengthy to serve as the core of a crash diagnostics process. In general, it is important to focus on those human factors issues that reflect (1) significant contributors to crashes in terms of their influence on

safety performance and (2) topics that can be addressed by the practitioner through roadway planning, design, and/or operations.

In this regard, several relevant human factors data sources [e.g., Wierwille et al., 2002; Campbell et al., 2012; Theeuwes and van der Horst, 2012; Theeuwes, 2021; Permanent International Association of Road Congresses (PIARC), 2016; PIARC, 2019a] make clear that four human factors topics in particular are key to the efficacy of roadways as information systems and the general safety performance of roadways: perception-response time, expectations, visibility, and workload. This toolbox provides more detailed descriptions and diagnostic questions associated with each of these key human factors-related contributors to crashes. The following summarizes each factor:

- Perception-Response Time: The facility should provide enough time for road users to perceive, then decide, and then respond/act.

- Expectations: The facility should be laid out logically, be consistent with road user expectations, and avoid confusing users.

- Visibility: The facility should support the visual perception and comprehension of relevant objects in the environment.

- Workload: The facility should not place demands on road users that are inconsistent with their inherent capabilities (e.g., perceptual/visual, decision-making, and physical capabilities).

As important as these contributing factors are to crashes, these factors should not be considered in isolation from one another or from other factors that might contribute to crashes. As noted earlier, errors made by road users do not generally reflect the breakdown or occurrence of a single factor; they reflect a confluence of factors that occur more or less simultaneously. Specifically, it is often the interactions among road users, vehicles, and the environment that lead to errors, conflicts, crashes, and fatalities (Dingus et al., 2006). As noted recently by Hauer (2020), crashes usually have more than one cause, and “[a] crash cause is a circumstance or action that, were it different, the frequency of crashes and/or their severity would be different” (p. 4). Thus, an effective framework and methodology for the diagnostic assessment of crashes must include not just a review and analysis of relevant road user, environmental, and vehicle factors, but also the interactions between these factors (see also the HFIM from Campbell et al., 2018). For example, a crash does not generally happen just because a driver is older; rather, it might happen to an older driver driving at night, under bad weather conditions, when faced with a sign that may be wordy, complicated, damaged, or worn out.

PIARC Human Factors Guidelines highlights “three classes of human factors accident triggers in the man-road interface”:

- The road should give the driver enough time to react safely (time).

- The road must offer a safe field of view (visibility).

- The road has to follow the driver’s perception logic (expectations) (PIARC, 2016, p. 13).

The HFG (Campbell et al., 2012) is closely aligned with these highlights in the PIARC document, with numerous guidelines addressing the importance of time, visibility, and expectations. The HFG—consistent with general guidance for all person-machine interactions—also focuses on the crucial topic of demand or workload. Indeed, the crash record makes it clear that the overwhelming majority of crashes in which driver error plays a role involve situations in which the demands of the driving task exceed the driver’s capabilities (Treat et al., 1979; Singh, 2015). Thus, to time, visibility, and expectations, workload is added to those human factors topics that reflect key contributors to crashes.

Key Concepts

- While the great majority of crashes involve some type of driver error, it is often the interactions among road users, vehicles, and the environment that lead to crashes.

- Many crashes occur when the demands of the roadway environment exceed the capabilities of the roadway user.

- Roadways are always sending messages to the road user—the key is to design the road so that the right messages are provided at the right time.

- Four human factors issues are key to the safety performance of roadways: (1) perception-response time, (2) driver expectations, (3) visibility, and (4) workload/demand.

2.4 Diagnostic Questions Related to the Contributing Factors to Roadway Crashes

As a designer or traffic engineer, consider if and how your roadway places demands on users that might be greater than their inherent capabilities:

- Consider the individual roadway elements (e.g., signs, markings, traffic lights, lane widths, shoulder widths) present within the facility under study:

- What messages are these individual elements likely to be communicating to the typical road user?

- Is this the message you intend to communicate?

- If not, consider how to communicate your message more effectively.

- Is the message being communicated in the right way?

- If not, consider alternative methods for communicating to road users [e.g., adding signs to augment lane markings, adding dynamic roadway features, or Transportation Systems Management and Operations (TSM&O) strategies to support timely communications to road users (AASHTO, n.d.b)].

- Is the message being communicated at the right time and place?

- If not, consider relocating signs or other elements to a location where they will be more effective.

- Is this the message you intend to communicate?

- What messages are these individual elements likely to be communicating to the typical road user?

- Consider both the individual roadway elements (e.g., signs, markings, traffic lights, lane widths, shoulder widths) and the broader facility under study:

- Does it seem that road users may have insufficient time to respond to typical demands?

- If yes, see Chapter 5: “Perception-Response Time as a Contributing Factor to Crashes” for more information.

- Does it seem that some roadway features may be inconsistent with what users might expect or include abrupt changes in driving requirements?

- If yes, see Chapter 6: “The Role of Expectations in Road User Behavior” for more information.

- Does it seem that road users may have problems seeing or perceiving key roadway elements under a range of operating conditions (e.g., day and night)?

- If yes, see Chapter 7: “The Role of Visibility in Road User Behavior” for more information.

- Does it seem that some typical or required tasks associated with the roadway may place excessive demands on the capabilities of a typical user?

- If yes, see Chapter 8: “Task Demand as a Contributing Factor to Crashes” for more information.

- Does it seem that road users may have insufficient time to respond to typical demands?