Development of a MASH Barrier to Shield Pedestrians, Bicyclists, and Other Vulnerable Users from Motor Vehicles (2024)

Chapter: 3 Agency Survey

CHAPTER 3

Agency Survey

This chapter describes the survey designed to solicit information from transportation agencies and design consultants on

- Projects/design contexts in which a barrier to separate vulnerable users from motor vehicles is needed,

- Existing standard drawings of a barrier to separate vulnerable users from motor vehicles,

- Implemented retrofit options of an existing barrier to separate vulnerable users from motor vehicles, and

- Preferences in terms of barrier design options.

The information collected served to determine the initial parameters and improved characteristics to be considered while developing preliminary design options for the proposed system. A copy of the survey instrument is provided in Appendix A. The survey was designed to incorporate a logic to redirect the respondents to different survey portions on the basis of the offered responses.

The survey was administered online with Qualtrics and was sent to all state DOTs and Ontario, Canada. The survey was distributed via email. A total of 25 state DOTs responded to the submitted survey.

Since the survey employed logic that redirected respondents to specific questions on the basis of certain responses, the total number of responses to specific questions may not equal the number of participants in the survey. Conversely, some questions allowed for multiple selections to be made, which resulted in a total number of responses greater than the number of participants in the survey. Although the survey was submitted to both state DOTs and design consultants, the project team received responses primarily from state DOTs. Followings are the 25 state and local agencies that participated in the survey: Alaska, Arkansas, Baltimore City, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York State, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington State, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Survey Responses

Needs and Solutions at Locations with Barrier Separation Needs

Almost all the respondent agencies (the exception being the Arkansas DOT) indicated that they have locations where barrier separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles is a consideration. Table 7 shows the solutions some respondent agencies described for separating vulnerable users from motor vehicles.

Table 7. State agency comments on consideration for barrier separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Colorado | We will have a barrier between pedestrians and roadway for any situations with a speed limit of >45 mi/h. |

| Florida | We address it where we can with the use of concrete barriers, especially for high-speed conditions and on bridges. |

| Louisiana | Typically, we do not install a barrier, since doing so would reduce the already limited space available for pedestrians. Also, the additional weight of the barrier could cause structural issues when installed on a bridge. Typically, the only thing separating pedestrians from traffic is an 8- to 10-in. curb. |

| Minnesota | Typically move bus stations out of the clear zone rather than install a barrier. |

| Missouri | Depending on traffic volumes, speed, and other factors, we will install pedestrian barriers. |

| New York | We often install a barrier, but traffic speeds, offsets, and vehicular and pedestrian volumes are also taken into consideration. |

| Oregon | ODOT [Oregon Department of Transportation] has guidance to consider installing a barrier—usually concrete barrier—for high-speed locations. |

| Texas | In some instances, an MBGF [metal beam guard fence] application or CTB [concrete traffic barrier] application will be used to provide protection. |

| Utah | We often have barrier located between pedestrians and vehicles on bridges or through interchanges, but we are developing a standard for temporary traffic control that does not include barrier separation—at least not anything capable of protecting a pedestrian from a TL-3 hit. We install cast-in-place barrier on a case-by-case basis. Could use guidance on standard practice and design. |

Agency Standard Barriers

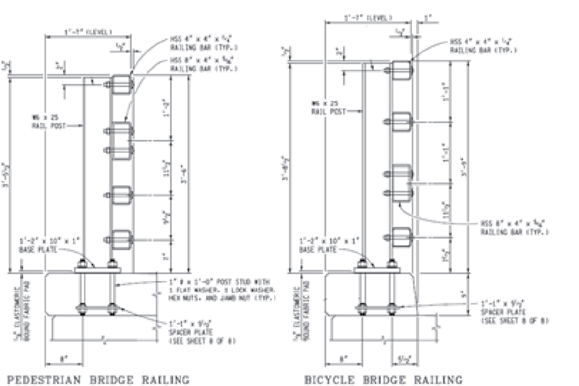

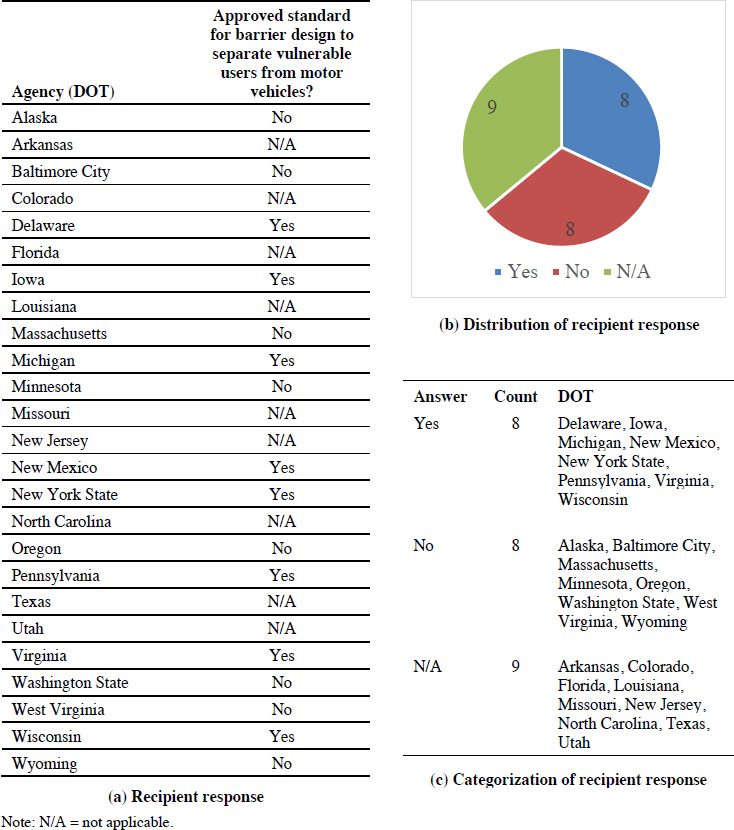

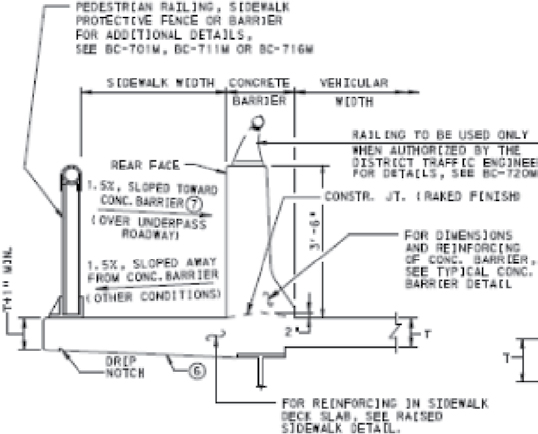

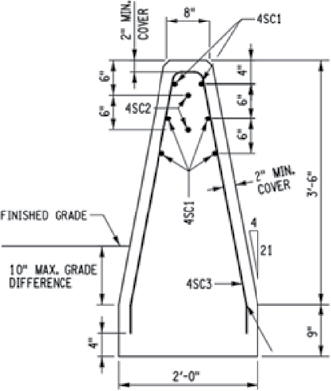

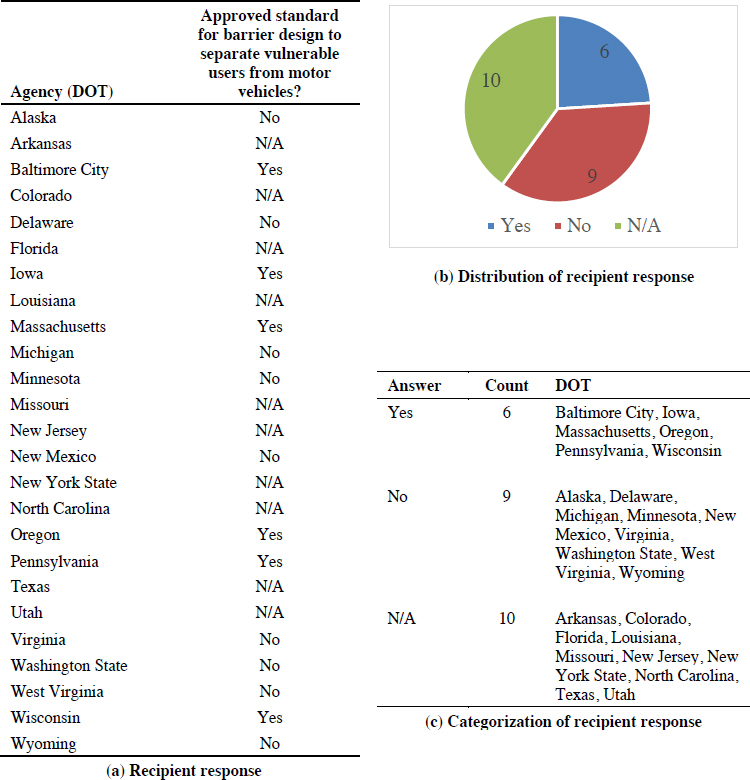

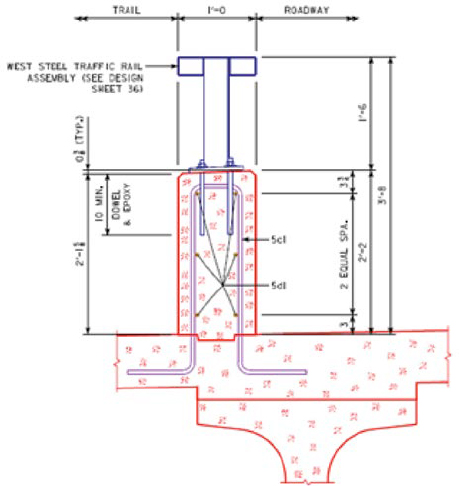

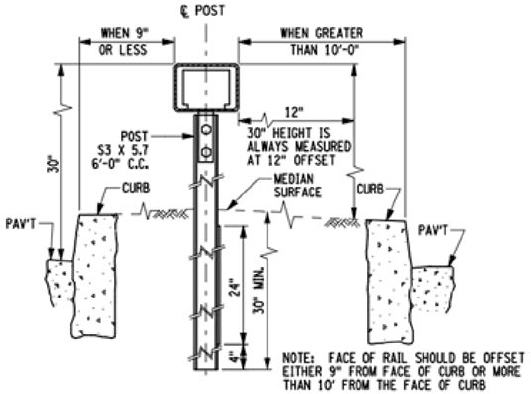

The agencies were asked whether they had approved standard drawings in their roadside safety hardware standard that they could use to separate vulnerable users from motor vehicles (see Figure 20). Eight state agencies indicated that they had an approved standard and provided related information (Tables 8 through 11).

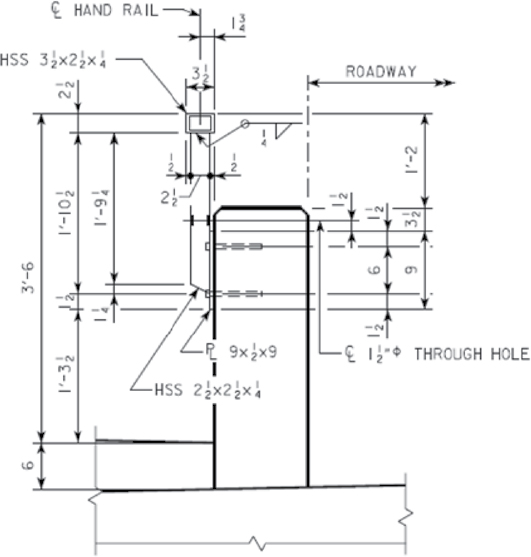

On the basis of the feedback, it appears that the majority of the respondent DOTs utilize either a concrete barrier or a combination concrete-metal (on top) barrier as their standard for those locations where a barrier separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles is needed. There are a few exceptions, such as the Delaware DOT, which indicated use of a standard 31-in. guardrail in roadway areas, with the understanding that this is not a statewide practice but used only in certain areas. The New York State DOT also specified use of a heavy-post blocked-out (HPBO) beam median barrier, indicating that “the face towards the path users shields them from its posts.” The New York State DOT also identified use of a box-beam median barrier with rounded corners, indicating the post corners are not directly accessible to path users since the posts are underneath the rail and have paddles that extend up into transverse slots in the bottom of the rail.

Agency Nonstandard Barriers

The agencies were asked whether they had nonstandard barriers they could utilize to separate vulnerable users from motor vehicles (Figure 21). Six agencies indicated that they had a nonstandard barrier for such use; however, only New York State provided details regarding the nonstandard system currently used:

If the path is to be closer than 3 ft to the barrier, then a barrier must be used that does not have any post corners exposed to the path users. We have one special option for barriers that satisfy this condition: roadside box or roadside HPBO with timber rail bolted to the back (path side) of the posts. This typically consists of a pressure-treated 2 × 12 or 2 × 10 bolted to the flange of the steel post so that the top of the plank is an inch or two above the top of post.

Table 8. State agency standards for barrier separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles: Delaware, Iowa, and Michigan.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Delaware | Some of our newer bridges are designed with a parapet separating pedestrians. Some roadway areas have guardrail installed. This is not a statewide practice, just certain areas. |

| We used standard F-shaped barrier on bridges and standard 31-in. guardrail in roadway areas. | |

| Iowa | Iowa state provided a rendering of their standard barrier used for shared-use path. |

| Michigan | Michigan provided a picture of the standard barrier they use for shared-use path. |

Table 9. State agency standards for barrier separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles: New Mexico and Pennsylvania.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| New Mexico |

https://dot.state.nm.us/content/dam/nmdot/Plans_Specs_Estimates/2019_Standard_Drawings.pdf (543-05)

|

| Pennsylvania | PennDOT has standards for barriers on bridges for high-speed environments, see attached. However, for along highways, if a buffer cannot be provided, standard F-shape concrete barriers are typically used. |

For bicycle requirements, they follow AASHTO requirements, meaning that height is 42 in. |

Note: PennDOT = Pennsylvania Department of Transportation.

Table 10. State agency standards for barrier separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles: Virginia and Wisconsin.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

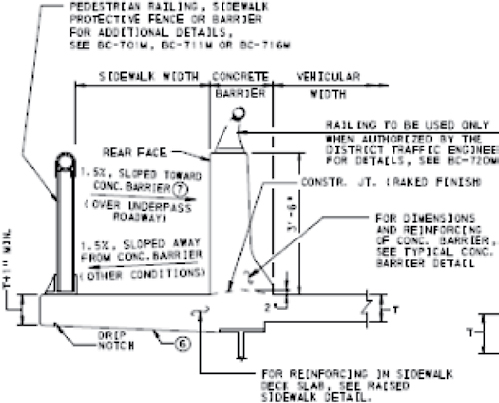

| Virginia | At this time, we use W-beam to shield the parapet on bridges. The shared-use path transitions away from the roadway beyond the bridge. |

| Standard 27¾-in. W-beam or MGS is used to shield the parapet, which is then terminated with a W-beam energy-absorbing terminal. | |

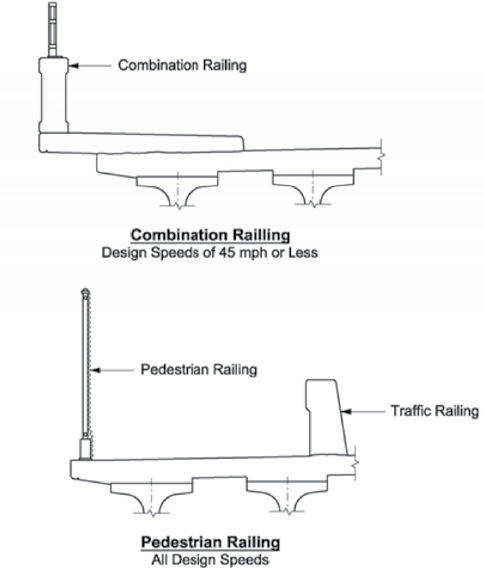

| Wisconsin | https://wisconsindot.gov/dtsdManuals/strct/manuals/bridge/ch30.pdf |

| https://wisconsindot.gov/rdwy/fdm/fd-11-35.pdf#fd11-35-1.6 | |

From the manuals provided, the minimum height of a barrier for shared-use path is 42 in. |

|

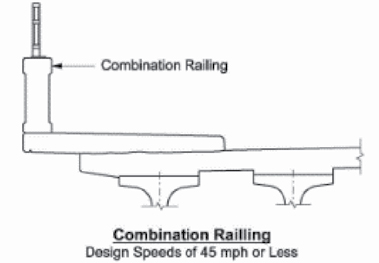

| “Combination Railings can be used concurrently with a raised sidewalk on roadways with a design speed of 45 mph or less. Combination Railings can be composed of, but are not limited to: single slope concrete parapets with chain link fence, vertical face concrete parapets with tubular steel railings such as type 3T, and aesthetic concrete parapets with combination type C1-C6 railings.” |

Table 11. State agency standards for barrier separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles: New York State.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

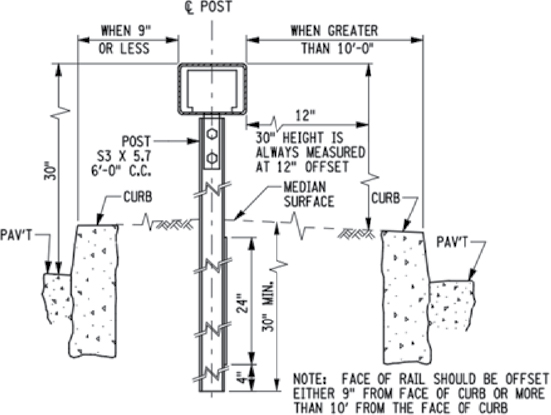

| New York State |

If the path is to be closer than 3 ft to the barrier, then a barrier must be used that does not have any post corners exposed to the path users. We have three standard barrier options (…).

Box Beam Median Barrier https://www.dot.ny.gov/main/business-center/engineering/cadd-info/drawings/standard-sheets-us-repository/606-05.pdf

|

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

|

HPBO (Heavy-Post Blocked-Out) Median Barrier https://www.dot.ny.gov/main/business-center/engineering/cadd-info/drawings/standard-sheets-us-repository/606-09_050814e2_0.pdf  Single-Slope Concrete Median Barrier https://www.dot.ny.gov/main/business-center/engineering/cadd-info/drawings/standard-sheets-us-repository/606-14_090612.pdf

|

Table 12 and Table 13 provide additional information on testing and evaluation of existing barriers used by the DOTs for separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles.

Agency Needs

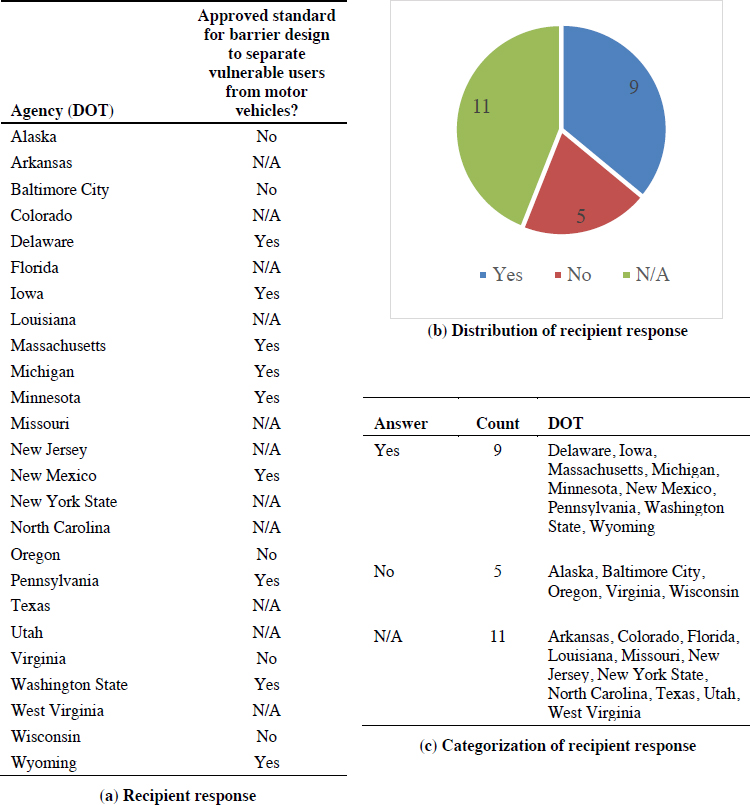

The agencies were asked whether the barrier options they were using satisfied all their needs, given considerations in regard not only to errant motorists, but also to protecting vulnerable users. Figure 22 illustrates the feedback obtained from the respondent agencies.

Tables 14 through 18 record feedback from the respondent agencies regarding a general description of the roadway types (e.g., functional class or design/posted speed or both) and pedestrian/bicyclist facilities (e.g., bike lanes, shared-use paths, separated bikeways) where a barrier to separate vulnerable users from motor vehicles could be helpful.

Tables 19 through 22 present feedback from the respondent agencies regarding required/ desirable characteristics for the development of a new barrier for separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles.

Tables 23 through 25 summarize the roadside barriers currently available/in use by the agencies for separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles.

Table 12. Testing/evaluation information from state agencies on reported barriers used for separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles: Massachusetts, New Mexico, Oregon, Virginia, and Wyoming.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Massachusetts | Barrier was used to separate a multiuse path from an Interstate on a bridge. Barrier was just a standard bridge rail that had previously been crash tested to NCHRP Report 350 [29]. |

| New Mexico | Since we do not have testing facilities, we use other approved devices from other states. |

| Oregon | We have been using Tuff Curb with vertical delineators for our first physically separated bike lanes on state facilities. We selected this product because it is included on ODOT’s Qualified Products List (QPL), which means it has been crash tested and approved for use on state highways. Tuff Curb is currently only approved in the QPL as a temporary traffic control device, so we will need to do before/after studies on our pilot bikeway installations to get it approved for permanent use. |

| Virginia | Standard 27¾-in, W-beam or MGS is used to shield the parapet, which is then terminated with a W-beam energy-absorbing terminal. |

| Wyoming | We used our standard box beam guardrail that is used to mitigate against roadside hazards. |

Table 13. Testing/evaluation information from state agencies on reported barriers used for separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles: Iowa.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Iowa |

The concrete safety shape barrier we use as the basis of our standard separator has been crash tested, though the steel railing attachment has not. Our TL-2 nonstandard separator is based on a crash tested 32-in. vertical parapet, but the back-mounted steel railing attachment has not been crash tested.

(Iowa DOT nonstandard TL-2 separator) |

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

Our TL-4 nonstandard separator is a Michigan BR 27C barrier modified by the Vermont Agency of Transportation to include a bicycle railing. Both nonstandard design evaluations can be found here: https://static.tti.tamu.edu/tti.tamu.edu/documents/FHWA-RD-93-058.pdf

(Iowa DOT nonstandard TL-4 separator) While many would characterize our separators as NCHRP Report 350–compliant [29], their actual crash testing was performed under NCHRP Report 230 (30) with the possible exception of the concrete safety shape. The barriers in NCHRP Report 230 were carried forward under NCHRP Report 350. |

Table 14. Additional information from state and local agencies on facilities needing barrier separation for vulnerable users: Alaska, Baltimore City, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, and New Mexico.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Alaska | Major arterial or above, speed limits ≥5 mi/h, and crash data to suggest the barrier is needed. In most cases, that would lead to separating the path/trail behind a ditch and/or outside of the clear zone. Where that is not practicable and crash data warrant further protection, then MASH-tested guardrail or concrete barrier have been our current solutions of choice. |

| Baltimore City | Arterial roadways with a low posted/target speed of 25 mi/h to 30 mi/h, but with a high 85th percentile speed, that include a mix of bicycle and pedestrian traffic based on adjacent land uses (e.g., parks, dense residential). |

| Colorado | We provide barrier between roadway and pedestrian when speed is >45 mi/h. |

| Delaware | 45- to 50-mi/h roadways that run adjacent to shared-use paths. It is mostly when the shared-use path and roadway merge together at a pinch point (e.g., bridge, ROW issue). |

| Florida | We use concrete barriers on bridges and where there are higher-speed conditions. Florida does not have the solution you are seeking. |

| Louisiana | This is typically a concern in urban areas where the sidewalk is carried across the bridge. These routes are typically high ADT but low speed (45 mi/h or less), and the only thing separating pedestrians from the vehicles is an 8- to 10-in. curb. |

| Michigan | Bridges with posted speeds of 45 mi/h or greater and a pedestrian and/or bicyclist facility. Barrier separation is required on bridges with pedestrian/shared-use facilities and a posted speed limit greater than 40 mi/h. |

| Minnesota | Considering a BRT system in a 50-mi/h road using 14-in. platforms located in the clear zone. Arterials, low and high speed, shared-use trails. |

| New Mexico | Several busy arterials; barrier has been used for pedestrian and bicycle facilities on bridges. The facilities have been separated from vehicles with a barrier and railing has been installed for the pedestrian protection from drop-offs. |

Note: ADT = average daily traffic; BRT = bus rapid transit.

Table 15. Additional information from state and local agencies on facilities needing barrier separation for vulnerable users: Iowa, Missouri, New York State, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Iowa | Our highest need for separators is on bridges that carry both vehicles and shared-use paths (pedestrians/bicyclists). Approach roadways leading to these structures also require these separators. The new MASH-tested separator we have under development at MwRSF is a potential solution to most of these installations, since the majority occur in TL-2 conditions. However, our new MASH policy states that we cannot be the only state to employ any individual piece of barrier hardware. We need additional states to adopt our proposed separator in order for the Iowa DOT to use it. This project may provide a venue for other states to see this proposed bridge separator and consider its use. The Iowa DOT’s occasional needs for TL-4 separators can be handled by the use of TL-4 traffic barriers that meet the 42-in. minimum height specifications for this hardware (e.g. BR 27C, Texas T80HT), if those barriers are carried forward under MASH. We have not had other instances arise where similar positive separation of vulnerable users from traffic is necessary, but that does not mean we will never have this need. It would be beneficial to have ready options available for future applications of this type. |

| Missouri | Barrier construction is based on traffic volumes, speed, and other factors. This is done on a project-by-project need. We also work with our planning partners on their community needs for vulnerable road users. |

| New York State | Numerous such possibilities exist. The final decision generally comes down to a question of the likelihood that a path user might be struck by an errant vehicle. One common scenario involves a narrow corridor where a popular recreation path will need to be close to a high-volume, high-speed highway. Another scenario involves park areas where children could be path users adjacent to medium-speed park roads. A double standard exists, as urban sidewalks are not separated from high-volume urban traffic. “Paths” are more likely to receive special treatment. |

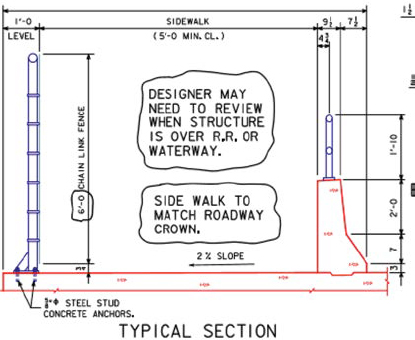

| Pennsylvania | When sidewalks are provided on bridges with a posted vehicular speed greater than 45 mph or structures longer than 200 ft (regardless of the speed), the sidewalk shall be protected by a barrier, unless waived by the Department. An example where the Department may waive the sidewalk barrier requirement is a structure longer than 200 ft. in an urban environment where a curbed approach walkway exists and the posted vehicular speed is less than or equal to 45 mph. When a barrier is required on a bridge to protect the sidewalk, the barrier shall be transitioned to the appropriate roadway protection device (e.g., guide rail, barrier, curb) beyond the end of the structure and maintain pedestrian access. |

| Texas | Higher-level functional classifications and those with higher design speeds would be likely candidates for a barrier to protect pedestrians on sidewalk. A barrier application for shared-use paths that are not significantly separated from the traveled way would also be helpful. |

| Virginia | We would like to have a positive barrier that can be used for the entire length of the shared-use path (or other path types) other than the W-beam. The W-beam must have a rail on the back to shield the posts if it remains adjacent to the path. |

| West Virginia | Most locations are multilane with TWLTLs and sidewalks on either side. Speed limits vary from 35 to 55 and are in urban locations. |

Note: TWLTL = two-way left-turn lane.

Table 16. Additional information from state agency on facilities needing barrier separation for vulnerable users: Oregon.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

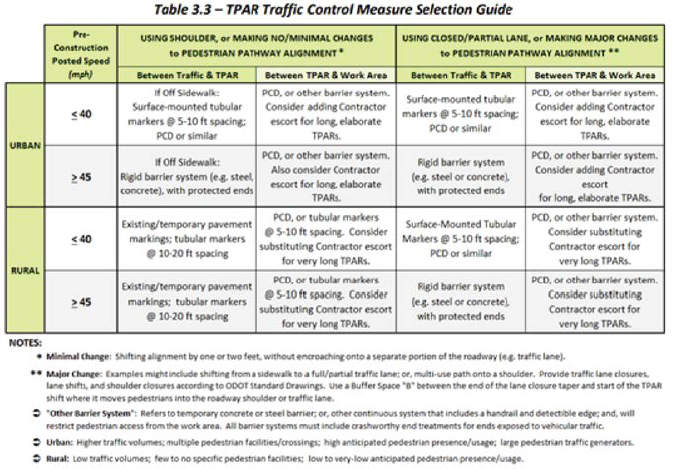

| Oregon |

ODOT will be adopting a separation chart similar to the draft AASHTO bike facility selection chart where speeds and volume are the primary factors. At slower speeds (say, 35 and below), the separation treatment does not need to redirect a motor vehicle; it only needs to be very visible, which means it probably needs a vertical component. The treatment needs to be sufficiently crashworthy that it does not cause an errant vehicle to lose control or become a hazard to the occupants or any nearby vulnerable road users. The treatment needs to be [able] to withstand a vehicle hit and not require extensive maintenance. At higher speeds (say 40 and above), the separation treatment does need to be capable of redirecting an errant vehicle. ODOT's Pedestrian and Bicycle Design guide includes a separation matrix that advises on where to physically separate bikeways from traffic based on speed and volume of the roadway. ODOT is currently finalizing the Blueprint for Urban Design, which includes an updated bikeway selection process, which is essentially the new FHWA Bikeway Selection model with minor modifications. ODOT has guidance in the Traffic Control Plans design manual for when to consider positive protection for pedestrians. See pages 85 & 86, table 3.3. https://www.oregon.gov/ODOT/Engineering/Docs_TrafficEng/TCP-Design-Manual.pdf

|

Note: TPAR = temporary pedestrian-accessible route.

Table 17. Additional information from state agency on facilities needing barrier separation for vulnerable users: Wisconsin.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Wisconsin |

The majority of bicycle accommodations in rural areas will be provided through paved shoulders and in urban areas through bike lanes. If a bridge or approaching highway has either pavement-marked bike lanes or is signed as a bicycle route and the bicycle accommodation is immediately adjacent to the bridge railing, the railing height should be a lower minimum of 42-in. If the bridge/highway is not marked or signed as a bicycle facility, then use the typical 32-in. barrier height on the bridge (i.e., even if the bridge/highway has a paved shoulder wider than typical paved width shoulder and is not marked or signed as a bicycle facility, use the typical barrier height). Refer to FDM 11-46-15 for additional information on bicycle accommodations. Two-way shared-use paths are required to be separated from the traveled way for all posted speeds with a 42-in. barrier wall, except that a 32-in. barrier wall may be considered if

Facilities Development Manual 11-35 <<https://wisconsindot.gov/rdwy/fdm/fd-11-35.pdf#fd1135>> There is criteria when inadequate separation cannot be provided from motor vehicles or along bridge structures, etc. https://wisconsindot.gov/rdwy/fdm/fd-11-35.pdf#fd11-35-1.6

|

Table 18. Additional information from state agency on facilities needing barrier separation for vulnerable users: Utah.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Utah |

We typically use barriers in and around freeways—for instance, at diverging diamond interchanges, we will use barrier on both sides of the median walkway. We will also in some cases place the walkway to the outside of the TL-3 parapet and use chain link for the outside railing. Arterials on structures, arterials at grade interchanges, diverging diamond interchanges, high-speed road with narrow ROW, separate light and heavy rail, routing pedestrians in the road during temporary traffic control.

Use of barrier for center walkway in a diverging diamond interchange |

Table 19. State and local agency feedback on the development of a new barrier for separation of vulnerable users: Alaska, Baltimore City, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Louisiana, and Massachusetts.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Alaska | Barrier should protect the vulnerable user but also at minimal increased risk to the motor vehicle user. |

| Baltimore City |

|

| Colorado | Preferably, the barrier would include standard crash-tested barrier with additional height or rail to provide appropriate requirements for pedestrians. Challenge has been that pedestrians/bikes are generally on an elevated sidewalk, so 42-in. barrier at roadway level is still too short for 42-in. rub rail at sidewalk height. Should have a concrete barrier and metal barrier options. Add-ons for pedestrian requirements should not affect the crashworthiness of the roadway barrier, i.e., create additional snagging points, etc. |

| Delaware | Meet TL-3 requirements. |

| Florida | We would like you to develop a steel railing with horizontal steel members for use in lower-speed conditions. We feel that a TL-2 test level is appropriate for this barrier. There would likely be horizontal members on the bicycle face as well to prevent snagging of the bicyclist on the steel posts. The challenge will be the termination of these barriers. There will be a lot of breaks in the barrier for driveways and side streets. We would want to see a TL-2 crashworthy end treatment. |

| Louisiana | It would be helpful if this was a retrofit type of detail that could be applied to bridges already in service, not just new construction. Also, I think deflection should be kept as low as possible, since the barrier should not excessively deform or break apart into the sidewalk area. It would be helpful if this was a retrofit type of detail that could be applied to roadways and sidewalks already in service, not just new construction. Also, I think deflection should be kept as low as possible, since the barrier should not excessively deform or break apart into the sidewalk area. For installations on bridges with sidewalks, a low-weight barrier would be preferred. |

| Massachusetts | In general, MassDOT will only consider barrier-separating motor vehicles from vulnerable road users in cases where a bridge is shared by both users. In those cases, we would be looking for a bridge-rail style design that meets MASH TL-4. |

Note: MassDOT = Massachusetts Department of Transportation.

Table 20. State agency feedback on the development of a new barrier for separation of vulnerable users: Iowa.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Iowa | For the Iowa DOT to be able to employ barriers that meet our own MASH policy on file with FHWA, they must have the full suite of crash tests for the test level, and all components of the complete system (transitions, end sections, joints, etc.) must be tested. This level of completeness currently results in an FHWA eligibility letter, which is what our policy prioritizes. It would be ideal if any new nonproprietary separator hardware had an FHWA eligibility letter and is adopted by multiple states, so that Iowa can use it and meet the 1st priority of our policy. And, again, we hope that this project can bring attention to our proposed MASH TL-2 bridge separation barrier with bicycle railing under development at MwRSF, in the hopes that other states will adopt it. |

Table 21. State agency feedback on the development of a new barrier for separation of vulnerable users: Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Mexico, New York State, and Oregon.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Michigan | Speed, facility (bridge versus roadway). Even though a 42-in. tall barrier is acceptable, the Michigan DOT prefers to use a 54-in.-tall barrier when it is necessary to shield a shared-use facility on a bridge. |

| Minnesota | Would need to have openings for transit users to access three BRT bus doors in a seamless fashion. Verify that the barrier selected is appropriate for the current and future roadway characteristics. |

| Missouri | We have currently not established that criteria. |

| New Mexico | Barrier need is assessed based on the test level requirement in the mainline, so it varies. |

| New York State | Barrier system needs to be free from sharp corners or edges that could injure a pedestrian or bicyclist who runs into them. The typical steel guide rail posts have quite hazardous corners. Rail systems for bicyclists need to be tall enough so that a bicyclist will not fall over them and into traffic. The barrier system exposed to vehicles needs to minimize the number and strength of any vertical elements that an impacting vehicle will be able to snag on. The system needs to be modular, with bolted connections, so that a damaged section may be readily replaced. |

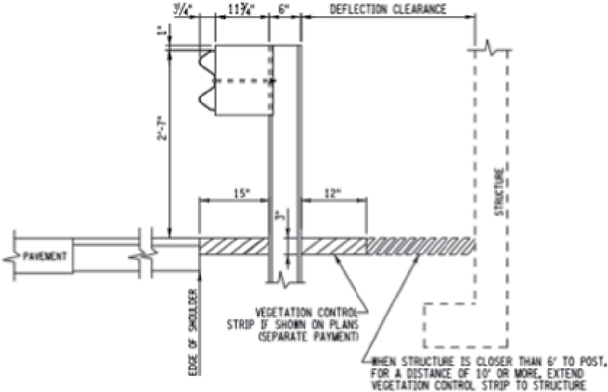

| Oregon | At slow speeds, visibility is the most important factor. Crashworthiness and low maintenance needs are other criteria. The barrier should ideally have some ability to redirect slightly errant vehicles, but that is not the most important criteria. At high speeds, the treatment’s ability to redirect vehicles becomes more of a factor. A treatment’s inability to fully redirect vehicles should not automatically disqualify it from further consideration by this research project or by an agency that is considering its use. Barriers need to be crashworthy and recoverable if a vehicle hits them (e.g., tested and on ODOT’s Qualified Products List), or outside of the clear zone. Maintenance is also a major consideration. Width is important; the narrower the barrier is the better to facilitate limited spaces. Deflection is important; if have to design for deflection and provide clear space for the deflection, [it] just uses the already limited space available for both vehicles and pedestrians. |

Table 22. State agency feedback on the development of a new barrier for separation of vulnerable users: Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

| Agency (DOT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| Pennsylvania | Meet MASH, ADA, and AASHTO bicycle requirements. |

| Texas | MASH-compliant for impacting vehicle. Minimal deflection into the area of the sidewalk or shared-use path. Easily installed for varying site conditions. |

| Utah | End treatments are an important element; in the photo of the DDI, we are using a sloped end section, which is probably OK in a DDI, where the geometry of the interchange limits speed. When we do pedestrian protection on a bridge, the question is always how to protect the blunt end. The other issue we deal with is in temporary applications, where we place precast barrier—how do we control deflection of the barrier into the pedestrian walkway? This is particularly important when we are placing barrier on a surface that we do not want to drive pins into. On top of structure, when you reach the end of structure, how to protect barrier blunt ends with limited ROW or space in general. In work zones, how to limit deflection with minimal damage to road surface. |

| Virginia | We would like to see a barrier that has a height range (42 in. plus additional height if zone of intrusion is considered) and, possibly, a handrail, if needed on the back side. Another consideration would be drainage along the wall and whether the barrier will have adjacent curb and gutter. |

| West Virginia | Concerns have been sight distance at intersections and width of barrier since sidewalk width is ess t an t. |

| Wisconsin | Barrier causing a pinch point on ADA sidewalk. Barrier working width and risk of having sidewalk close to a barrier. Bikes or pedestrians interacting with post or other edges. It seems that most information is provided from the motor vehicle’s needs. It is unclear if you wanted to have barriers to separate between bike/pedestrian or other types of vehicles (e.g., snowmobiles, ATVs). |

| Wyoming | The Wyoming DOT generally does not use barriers to separate pathway users from motor vehicles. We have installed box beam barrier in one location within the state that I am aware of, where pathway was within the clear zone of the highway. |

Note: DDI = diverging diamond interchange; ATV = all-terrain vehicle.

Table 24. Barriers state agencies reported using for separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles: New Mexico and Pennsylvania.

| Agency (DOT) | Drawing | Test Level | Testing Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

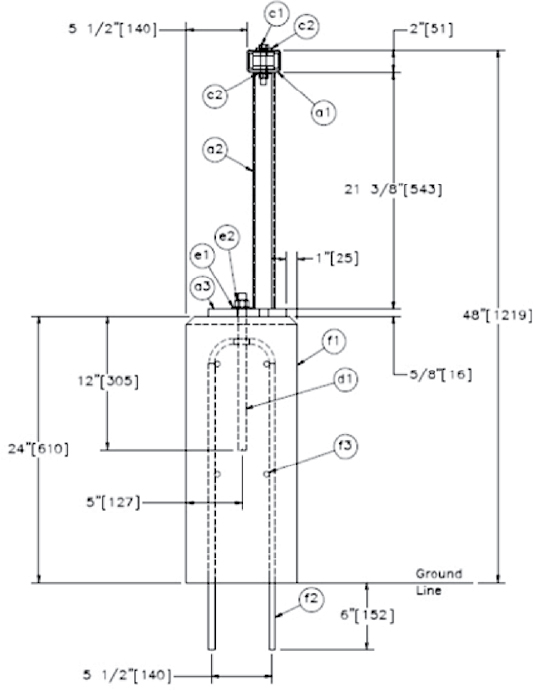

| New Mexico |  |

TL-2 and TL-5 | MASH (1) |

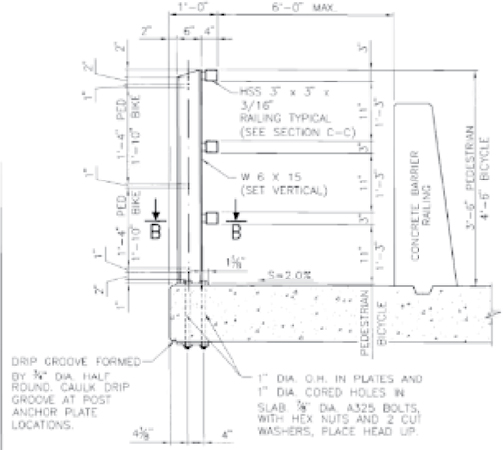

| Pennsylvania |  |

TL-4 | MASH (1) |

Table 25. Barriers state agencies reported using for separation of vulnerable users from motor vehicles: Iowa and New York.

| Agency (DOT) | Drawing | Test Level | Testing Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iowa |  |

TL-2 and TL-4 | MASH (1) |

| New York State |  |

N/A | N/A |

Conclusions

Most existing barrier systems that are currently utilized to shield vulnerable users from the roadway are rigid concrete or concrete and metal combination rails (a concrete parapet or concrete curb with metal railing on top). Some DOTs also utilize metal-only barrier options; however, those are generally considered for bridge applications. Currently, few existing systems of this type have passed MASH requirements for high-speed applications and can be directly implemented where needed. However, the cost for these combination concrete barriers is a factor that represents a limitation for some agencies, which would prefer having a more economical metal-only system option.

Table 26 and Table 27 summarize the design preferences suggested by the survey respondents for consideration during the development of the new barrier to shield vulnerable users from errant vehicles. The tables are organized to identify specific design preferences, barrier material type and minimum height, and system crashworthiness level (Table 26), and consider other barrier characteristics, such as working width, damage, and maintenance requirements (Table 27).

When the development of a metal-only barrier system is being considered, special attention needs to be given to dynamic deflection of the barrier when it is impacted by errant vehicles as well as working width and vehicle zone of intrusion. This is especially true for barriers that could potentially be implemented to shield vulnerable users from the roadway. In addition, maintenance is also an important factor for metal-only barriers. However, metal-only barriers can offer acceptable sight distance or drainage capability as compared with a concrete-only barrier option.

Specific design considerations also must be given to potential protruding railing elements or sharp post or rail edges. The barrier would need to be designed to account for potential interaction between vulnerable users and the barrier system; therefore, protruding and sharp elements would need to be avoided or shielded through a proper barrier design. In addition, consideration needs to be given to specific elements that might need to be added to comply with PROWAG/ADA requirements, with the understanding that add-ons for pedestrian requirements should not create additional snagging points for errant vehicles.

Some DOTs offered feedback with respect to the roadway-posted speed conditions where this new barrier should be deployed. While some DOTs specified that the majority of installations for these types of barriers would be for MASH TL-2 conditions—meaning low speeds (≤45 mi/h posted speed limit) and urban areas—a similar number of respondent DOTs indicated a need for a barrier meeting MASH TL-3 requirements (high posted speed of ≥45 mi/h).

Table 26. Design preferences for development of a new barrier to shield vulnerable users from errant vehicles.

| Design Consideration for Vulnerable Users | Material | Height | Road Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Table 27. Other considerations for development of a new barrier to shield vulnerable users from errant vehicles.

| Suggesting Agency | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Baltimore City |

|

| Florida |

|

| Iowa |

|

| Louisiana |

|

| Utah |

|

| Virginia |

|

| Wisconsin |

|

| West Virginia |

|

Recommendations

On the basis of the literature review and the survey responses, the research team compiled recommendations for barrier development (Table 28). Feedback was requested from the project panel to guarantee that the panel’s directions and guidance were followed through the preliminary options design phase.

Table 28. Research team recommendations for development of a new barrier to shield vulnerable users from errant vehicles.

| Required | Minimum barrier rail height: 42 in. [AASHTO Bike Guide (2) and AASHTO Bridge Design Specifications (8)]. |

| Required | No protruding objects (PROWAG)—objects with leading edges between 27 and 80 in. shall not protrude more than 4 in. |

| Preferred | Open metal-only rail. |

| Preferred | Handrail not required on pedestrian circulation paths (PROWAG); however, the Texas Department of Licensing and Registration requires handrails at 34 to 38 in. when running slope is 1:20. The TTI research team still suggests including this feature in the proposed barrier design. |

| Preferred | Safety toe rail or curb—serves as cane detection—maximum of 15 in. above sidewalk. It is preferred (and not required) as long as the bottom edge of metal barrier is lower than 27 in. If bottom edge is higher than 27 in., then this is required. |

| Preferred | MASH TL-3 (high-speed) conditions. |

Note: TTI = Texas A&M Transportation Institute.