Development of a MASH Barrier to Shield Pedestrians, Bicyclists, and Other Vulnerable Users from Motor Vehicles (2024)

Chapter: 2 Literature Review

CHAPTER 2

Literature Review

This chapter provides a review of U.S. and international literature on roadside safety devices and corresponding designs for vulnerable road users. The chapter consists of four key sections:

- Design characteristics of roadside safety devices for accommodating vulnerable users.

- Safety and planning implications of the relevant types of vulnerable road user facilities. This section also reviews relevant sections of the AASHTO Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities, 4th ed. (2) and the U.S. Access Board’s Public Right-of-Way Accessibility Guidelines (3) for public ROW and shared-use paths.

- Vegetation control methods for guardrail installations based on application conditions, and

- MASH testing standards.

Review of Crashworthy Roadside Barriers and Railings

While roadside safety barriers are not new, no current barrier has been both tested for redirective crashworthiness in relation to vulnerable road users and designed to specifically accommodate the needs of these vulnerable users. Such a barrier would need to safely redirect a vehicle away from a vulnerable user on the backside of the device during an impact and also provide necessary protections for that vulnerable user, such as handrails. The first portion of this literature review summarizes various barrier systems and guidelines for systems that involve vulnerable user protection.

While this project focused on developing a crashworthy pedestrian/bicyclist barrier, many agencies incorporate systems that focus solely on protecting pedestrian/bicyclist traffic from hazards. The Vermont Agency of Transportation has various types of barriers focused on protecting vulnerable road user traffic (4). Table 1 and Figure 1 show some general examples of the types of barriers that can be implemented to protect pedestrians and bicyclists.

The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) maintains standards on handrail designs (5). One such design is the PR11 pedestrian railing, which is a steel pipe rail system designed for pedestrian loads. This system has not been crash tested and is not intended for exposure to traffic. Table 2 shows the specifications for this railing, and Figure 2 shows the railing.

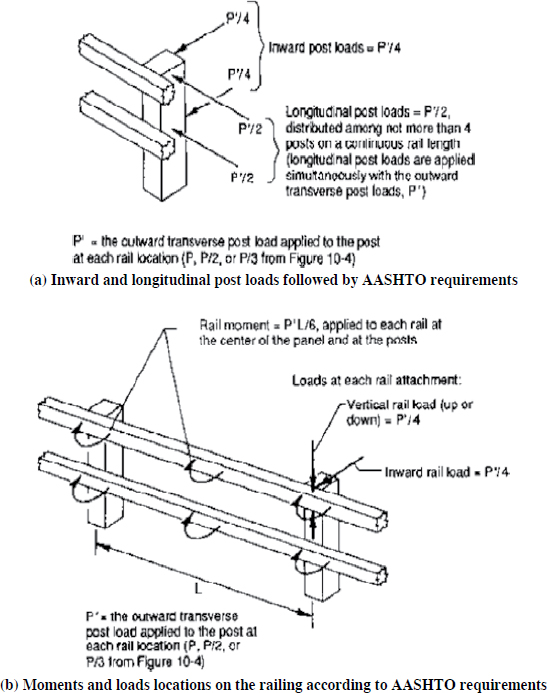

In addition to geometric requirements, the handrail must also be designed for strength considerations (6). AASHTO specifies loading requirements for both the rail elements and the posts. Figure 3 shows the minimum requirements for combination railing.

AASHTO also recognizes the need for accommodating the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (6). For example, AASHTO discusses the addition of certain elements to the rail system to aid in cane navigation. A rail or plate element along the base of the rail system will allow cane users to properly navigate along the length of the rail.

Table 1. General types of barriers (4).

| Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Hard | Fences (e.g., metal, wood, picket, pipe railing, wrought iron, chain-link), railings |

| Live | Vegetation, trees, bushes, plants |

| Terrain | Naturally occurring boundaries (e.g., rock walls) |

Table 2. TxDOT PR11 specifications (5).

|

Classification: Pedestrian.

Description: Six pipe rails, with 3.5-inch (in.) hollow structural section (HSS) steel pipe for the top rail and 2.375-in. HSS steel pipe for the lower rails. Its 5-in.-wide steel plate posts are spaced a maximum of 10 feet (ft) apart. |

|

Approved test criteria and level: The PR11 railing is designed for pedestrian loads only. It has not been crash-tested and it is not intended for exposure to traffic. If this railing is used on a bridge or culvert, it must be protected from vehicular impact by an approved bridge rail type. |

|

Nominal height: 42 in. |

|

Minimum height after maintenance overlays: 42 in. |

The Midwest Roadside Safety Facility (MwRSF) has investigated pedestrian rails that will be implemented near the roadside (7). The outside diameter of the gripping surface of a circular cross section of the handrail must be 2 in. Noncircular cross sections must be between 4 and 6.25 in. in perimeter measurement. Figure 4 explains the ADA dimensions for the noncircular cross section. According to the AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Specifications (also known as the Bridge Design Guide), the design height of the railing for pedestrians must be at a minimum of 42 in. above the walking surface (8). In addition, the railing must be able to support a live load of at least 50 pounds (lb)/ft, with a concentrated live load of 200 lb. Figure 4 also shows how the loading is applied to the railing.

According to the International Building Code, handrails must be between 34 and 38 in. above the surface (7). Handrails must have minimum clearance space of 1.5 in. between a wall and any other surfaces. Additionally, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) provides guidelines for railings. The standard railing must have a height of 42 in. The nominal diameter of posts, pipe railings, and intermediate railings should be a minimum of 1.5 in. OSHA provides a maximum of 8 ft of space between posts. With regard to loading requirements, OSHA requires the top railing to be able to support a 200-lb load at any point in any direction.

Barriers can incorporate nontraditional structural materials, including timber, high-density polyethylene (HDPE), fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) (7). These materials are typically used for handrails because of their durability and resistance to corrosion. Figure 5 shows examples of these barriers as well as others that are typically found. Table 3 and Table 4 show a comparative view of these types of materials versus traditional structural materials such as steel and aluminum.

In the review of barriers currently used to protect pedestrians and bicyclists from motor vehicles, the research team identified several designs that could provide inspiration for this project. Practical uses of these barriers are shown in Figure 6.

Review of Pedestrian and Bicyclist Facility Guidelines

AASHTO publishes two guides that are intended to be the national standard for pedestrian and bicyclist facility design:

- Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operation of Pedestrian Facilities (9, 10), also known as the Pedestrian Guide, and

- Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities, 4th ed. (2), also known as the Bike Guide.

Table 3. Comparison of materials used for barrier designs (7).

| Consideration/Condition | Material | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steel | Aluminum | PVC | FRP | HDPE | Wood | |

| Bending strength (fb) | Very high | High | Low | Medium | Very low | Very low |

| Modulus of elasticity (E) | Very high | High | Low | Medium | Very low | Medium |

| Brittleness | Low | Medium | High | High | Medium | High |

| Formability | Very high | Low | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cost | Medium | High | Medium | Very high | Medium | Low |

| Component weight | Medium | Very low | High | Low | High | Very high |

| Prefabricated connections | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Corrosion resistance | Medium | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high | Low |

| Temperature degradation | Very low | Very low | High | Low | Very high | Very low |

| Degradation from UV light exposure | Very low | Very low | High | High | High | Very low |

Note: UV = ultraviolet.

Table 4. Relevant material properties (7).

| Material | Bending Strength (fb) | Modulus of Elasticity (E) | Density | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| psi | kPa | ksi | MPa | lb/ft3 | kg/m3 | |

| Steel | 50,000 | 345,000 | 29,000 | 199,950 | 503 | 8,060 |

| Aluminum | 40,000 | 276,000 | 10,000 | 68,950 | 169 | 2,710 |

| FRP | 24,000 | 165,000 | 2,320 | 16,000 | 108 | 1,730 |

| PVC | 14,450 | 100,000 | 400 | 2,760 | 90 | 1,440 |

| HDPE | 4,800 | 33,000 | 200 | 1,380 | 59 | 950 |

| Wood | 1,550 | 11,000 | 1,700 | 11,720 | 31 | 500 |

Note: psi = pounds per square inch; kPa = kilopascals; ksi = kips per square inch; MPa = megapascals; lb/ft3 = pounds per cubic foot; kg/m3 = kilograms per cubic meter.

Many state DOTs either adopt the AASHTO guides as their prevailing design guidance or adapt the AASHTO guidelines with minor modifications. Therefore, this section reviews the AASHTO guidelines as the prevailing national design guidance for which there is consensus among all state DOTs.

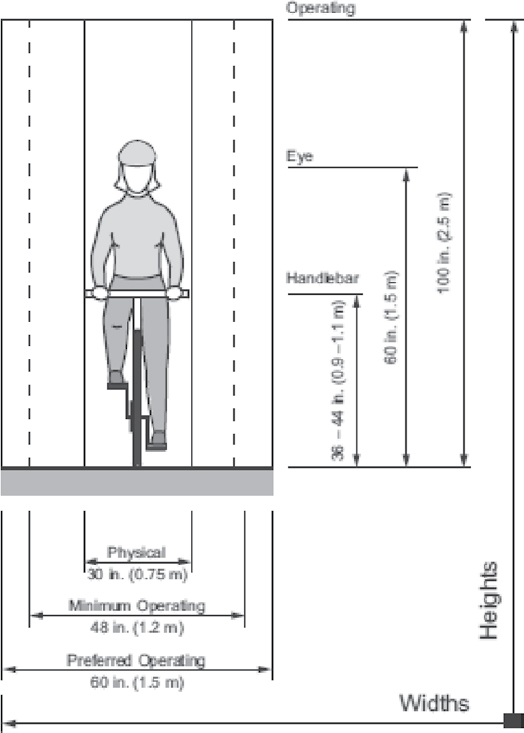

The 2012 AASHTO Bike Guide contains several design parameters that are relevant for barrier design: (a) bicyclist design dimensions, (b) bridge railing or barrier height, (c) side clearance on shared-use paths, and (d) bicycle handlebar rub railing (2). Figure 7 and Table 5 show the bicyclist dimensions from which several facility design dimensions are derived.

In Section 4.12.3 (“Bridges, Viaducts, Tunnels”), the Bike Guide says the following about barrier height (underline emphasis added, italics in original):

In locations where bicyclists will operate in close proximity to bridge railings or barriers, the railing or barrier should be a minimum of 42 in. (1.05 m) high. On bridges where bicycle speeds are likely to be high (such as on a downgrade), and where a bicyclist could impact a barrier at a 25 degree angle or greater (such as on a curve), a higher 48-in. (1.2-m) railing may be considered. Where a barrier is less than 42 in. (1.2 m) high, an aluminum rail with posts is usually mounted on top of the barrier. If the shoulder is sufficiently wide so that a bicyclist does not operate in close proximity to the rail, lower rail heights are acceptable. (2)

In the past, there has been considerable debate over a 42-in. versus a 54-in. railing height for bicyclists, and there was even inconsistency between previous editions of the Bike Guide and the Bridge Design Guide. However, the current editions of the Bike Guide and the Bridge Design Guide both specify a minimum railing/barrier height of 42 in. for bicyclists.

In Section 5.2.1 (“Shared-Use Path Width and Clearance”), the Bike Guide indicates that a minimum of 2 ft of clearance is needed for signs, poles, and other lateral obstructions (Figure 8). The accompanying text indicates that a minimum of 1 ft of clearance is needed for smooth features, such as a railing or fence (2).

The Bike Guide says the following about shared-use path clearance (underline emphasis added, italics in original):

At a minimum, a 2 ft (0.6 m) graded area with a maximum 1V [vertical]:6H [horizontal] slope should be provided for clearance from lateral obstructions such as bushes, large rocks, bridge piers, abutments, and poles. The MUTCD requires a minimum 2 ft (0.6 m) clearance to post-mounted signs or other traffic control devices (7). Where “smooth” features such as bicycle railings or fences are introduced with appropriate flaring end treatments (as described below), a lesser clearance (not less than 1 ft [0.3 m]) is acceptable. If adequate clearance cannot be provided between the path and lateral obstructions, then warning signs, object markers, or enhanced conspicuity and reflectorization of the obstruction should be used. (2)

Table 5. Bicyclist design dimensions from 2012 AASHTO Bike Guide (2).

| User Type | Feature | Dimension | |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Customary (in.) | Metric (m) | ||

| Typical upright adult bicyclist | Physical width (95th percentile) | 30 | 0.75 |

| Physical length | 70 | 1.8 | |

| Physical height of handlebars (typical dimension) | 44 | 1.1 | |

| Eye height | 60 | 1.5 | |

| Center of gravity (approximate) | 33–44 | 0.8–10 | |

| Operating width (minimum) | 48 | 1.2 | |

| Operating width (preferred) | 60 | 1.5 | |

| Operating height (minimum) | 100 | 2.5 | |

| Operating height (preferred) | 120 | 3.0 | |

In Section 5.2.2 (“Shared-Use Paths Adjacent to Roadways”), the Bike Guide says the following about separating shared-use paths and roadways (italics for emphasis added):

A wide separation should be provided between a two-way side path and the adjacent roadway to demonstrate to both the bicyclist and the motorist that the path functions as an independent facility for bicyclists and other users. The minimum recommended distance between a path and the roadway curb (i.e., face of curb) or edge of traveled way (where there is no curb) is 5 ft (1.5 m). Where a paved shoulder is present, the separation distance begins at the outside edge of the shoulder. Thus, a paved shoulder is not included as part of the separation distance. Similarly, a bike lane is not considered part of the separation; however, an unpaved shoulder (e.g., a gravel shoulder) can be considered part of the separation. Where the separation is less than 5 ft (1.5 m), a physical barrier or railing should be provided between the path and the roadway. Such barriers or railings serve both to prevent path users from making undesirable or unintended movements from the path to the roadway and to reinforce the concept that the path is an independent facility. A barrier or railing between a shared-use path and adjacent highway should not impair sight distance at intersections, and should be designed to limit the potential for injury to errant motorists and bicyclists. The barrier or railing need not be of size and strength to redirect errant motorists toward the roadway, unless other conditions indicate the need for a crashworthy barrier. Barriers or railings at the outside of a structure or a steep fill embankment that not only define the edge of a side path but also prevent bicyclists from falling over the rail to a substantially lower elevation should be a minimum of 42 in. (1.05 m) high. Barriers at other locations that serve only to separate the area for motor vehicles from the side path should generally have a minimum height equivalent to the height of a standard guardrail.

When a side path is placed along a high-speed highway, a separation greater than 5 ft (1.5 m) is desirable for path user comfort. If greater separation cannot be provided, use of a crashworthy barrier should be considered. Other treatments such as rumble strips can be considered as alternatives to physical barriers or railings, where the separation is less than 5 ft (1.5 m). However, as in the case of rumble strips, an alternative treatment should not negatively impact bicyclists who choose to ride on the roadway rather than the side path. (2)

In Section 5.2.10 (“Bridges and Underpasses”), the Bike Guide says the following about separating shared-use paths and roadways (italics for emphasis added):

A bridge or underpass may be needed to provide continuity to a shared-use path. The “receiving” clear width on the end of a bridge (from inside of rail or barrier to inside of opposite rail or barrier) should allow 2 ft (0.6 m) of clearance on each side of the pathway, as recommended in Section 5.2.1, but under constrained conditions may taper to the pathway width.

Protective railings, fences, or barriers on either side of a shared-use path on a stand-alone structure should be a minimum of 42 in. (1.05 m) high. There are some locations where a 48-in. (1.2 m) high railing should be considered in order to prevent bicyclists from falling over the railing during a crash. This includes bridges or bridge approaches where high-speed, steep-angle (25 deg or greater) impacts between a bicyclist and the railing may occur, such as at a curve at the foot of a long, descending grade where the curve radius is less than that appropriate for the design speed or anticipated speed.

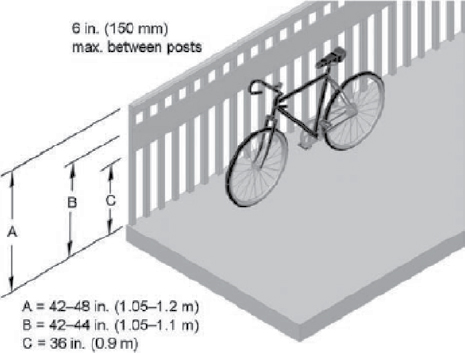

Openings between horizontal or vertical members on railings should be small enough that a 6 in. (150 mm) sphere cannot pass through them in the lower 27 in. (0.7 m). For the portion of railing that is higher than 27 in. (0.7 m), openings may be spaced such that an 8 in. (200 mm) sphere cannot pass through them. This is done to prevent children from falling through the openings. Where a bicyclist’s handlebar may come into contact with a railing or barrier, a smooth, wide rub rail may be installed at a height of about 36 in. (0.9 m) to 44 in. (1.1 m), to reduce the likelihood that a bicyclist’s handlebar will be caught by the railing (see Figure 5-11). (2)

Figure 9 shows Figure 5-11 from the Bike Guide.

The edition of the AASHTO Pedestrian Guide referenced under this project was published in 2004 (9), 8 years prior to the publication of the 2012 AASHTO Bike Guide. The discussion of shared-use paths in Chapter 3, “Pedestrian Facility Design” of the 2004 AASHTO Pedestrian Guide refers extensively to the most recent (at that time) AASHTO Bike Guide (the 1999 edition). The design dimensions are substantially unchanged in the 2012 AASHTO Bike Guide (2):

- Clearance zone of 2 ft on side of shared-use path and

- Minimum of 5 ft of separation between roadways and shared-use path.

The 2004 AASHTO Pedestrian Guide (9) also refers extensively to U.S. Access Board guidelines when discussing the accessibility of shared-use paths to persons with disabilities. The most recent accessibility guidelines at that time were published in 1999.

Because the 2004 edition of the AASHTO Pedestrian Guide is 20 years old and has extensive references to other design guidelines that have since been updated, the research team used the most recent versions of incorporated references to determine design parameters. An updated version of the AASHTO Pedestrian Guide was published in 2021, after completion of this phase of NCHRP Project 22-37 (10). The guidance in this new version is in line with the decisions made on this project.

The ADA was enacted as national law in 1990 and prohibited discrimination against individuals with disabilities. The U.S. Access Board is the federal agency that was charged with developing national standards to ensure compliance with the ADA (3).

The U.S. Access Board has worked with numerous stakeholders over the past two decades to develop specific guidance for how best to accommodate persons with disabilities in transportation and public ROW settings. In late 2019, the prevailing guidance (not yet law) was the Public Right-of-Way Accessibility Guidelines (PROWAG). The U.S. Access Board published the initial PROWAG in the Federal Register on July 26, 2011, with the intended application being on “sidewalks, pedestrian street crossings, pedestrian signals, and other facilities for pedestrian circulation and use.” The U.S. Access Board issued a supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking on February 13, 2013 (78 FR 10110). The accessibility guidance in this supplemental notice was essentially the same as that issued in July 2011, but it was issued to clarify that shared-use paths should meet the same accessibility standards as sidewalks and pedestrian street crossings. The final rule, “Accessibility Guidelines for Pedestrian Facilities in the Public Right-of-Way” (36 CFR Part 1190) was issued August 8, 2023, after the work for NCHRP Project 22-37 had been completed. Although the 2011 and 2013 PROWAG guidance had not been enacted as law at the time this research was conducted, many states and cities had adopted (or adapted with minor changes) PROWAG as part of their roadway design standards. Therefore, the research team included a review of PROWAG, since it was the prevailing national consensus on accommodating persons with disabilities in transportation facilities. The following discussion of PROWAG refers to the February 13, 2013, supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking (78 FR 10110).

PROWAG contains several design parameters that are relevant for barrier design:

- No protruding objects,

- Bottom edge treatment (cane detection), and

- Handrail.

These parameters are summarized in the following sections.

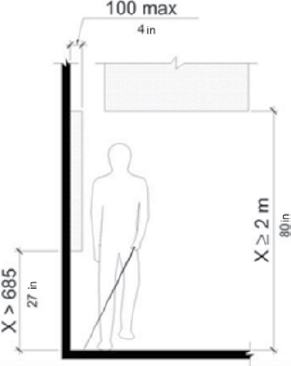

Section R402 of PROWAG deals with protruding objects in the pedestrian circulation path. Section R402.2 indicates the following (also see Figure 10):

Objects with leading edges more than 685 mm (2.25 ft) and not more than 2 m [meters] (6.7 ft) above the finish surface shall protrude 100 mm (4 in) maximum horizontally into pedestrian circulation paths.

Section R402.3 indicates the following for post-mounted objects (see Figure 11):

Where objects are mounted on free-standing posts or pylons and the objects are 685 mm (2.25 ft) minimum and 2030 mm (6.7 ft) maximum above the finish surface, the objects shall overhang pedestrian circulation paths 100 mm (4 in) maximum measured horizontally from the post or pylon base. The base

dimension shall be 64 mm (2.5 in) thick minimum. Where objects are mounted between posts or pylons and the clear distance between the posts or pylons is greater than 305 mm (1.0 ft), the lowest edge of the object shall be 685 mm (2.25 ft) maximum or 2 m (6.7 ft) minimum above the finish surface. (2)

Section R409 of PROWAG deals with handrails and indicates their need on ramps but not necessarily on level pedestrian circulation paths. Section R409.1 says,

Handrails are required on ramp runs with a rise greater than 150 mm (6 in) (see R407.8) and stairways (see R408.6). Handrails are not required on pedestrian circulation paths. However, if handrails are provided on pedestrian circulation paths, the handrails must comply with R409 (see R217). The requirements in R409.2, R409.3, and R409.10 apply only to handrails at ramps and stairways, and do not apply to handrails provided on pedestrian circulation paths.

Section R409.4 of PROWAG deals with handrail height:

Top of gripping surfaces of handrails shall be 865 mm (2.8 ft) minimum and 965 mm (3.2 ft) maximum vertically above walking surfaces, ramp surfaces, and stair nosings. Handrails shall be at a consistent height above walking surfaces, ramp surfaces, and stair nosings.

A review of literature by Sarkar attempted to subdivide different types of separations based on their unique physical and regulatory attributes and compared their performance in safety, equity, comfort, and convenience to the different road users (especially pedestrians and bicyclists) (11). The review found that there are four types of separations: (a) horizontal separation, (b) time separation, (c) vertical separation, and (d) soft separation.

Each of these types of separation requires different design and planning requirements that use physical, psychological, visual, and legal tools to eliminate conflicts. Sarkar’s work also discusses the performance of each type of separation in eliminating or promoting the following:

- Elimination of conflicts;

- Safety of vulnerable groups such as the elderly, children, and the physically/mentally impaired;

- Elimination of barriers for non-motorists;

- Optimal use of public space for outdoor pedestrian activities;

- Equitable use of the public space;

- Comfort and convenience; and

- Ensuring conformance. (11)

Separating vulnerable users from traffic can also help improve both safety and comfort of all roadway users. A study by Sanders examined the design preferences regarding multimodal roadways in a policy era focused on complete streets (12). The study found that alignment between drivers and cyclists for roadway designs can meet the needs of both user groups while sharing

the road, with both groups preferring greater separation on multilane roadways. The findings also support past research on bicyclists’ preferences and U.S. federal policy encouraging more substantial accommodation for cyclists on roadways. In addition, with the movement toward complete streets, practitioners need an understanding of roadway designs that maximize comfort and safety for all roadway users. More specifically, Sanders presented findings from research exploring perceptions of adult bicycling risks, experiences bicycling, and roadway design preferences among bicycling drivers, nonbicycling drivers, and nondriving bicyclists in the San Francisco Bay Area. The results showed that bicyclists of all types—and particularly potential cyclists—prefer greater separation from motorists. Also, the results provided new information about motorists’ preferences for sharing the road with bicyclists, indicating that motorists also prefer greater separation. These findings suggest an alignment between roadway user groups’ design preferences for multilane commercial streets and provide additional evidence of the benefits of complete streets for all roadway users. Methodologically, these findings also suggest advantages from studying the preferences of multiple user groups regarding shared facilities.

In another study by Sanders, the author examined roadway design preferences when bicycling alone, bicycling with children, and driving on multilane commercial streets (13). The findings were based on results from a survey exploring attitudes toward driving and bicycling, bicycling habits, barriers to bicycling, and roadway design preferences among Michigan residents. Regarding roadway design preferences, respondents were asked a series of questions about their level of comfort and experience riding and driving on seven different roadway designs. The findings overwhelmingly suggested a preference for more bicycle accommodations and more separated facilities. Seventy-five percent of respondents indicated that separated bicycle facilities would encourage them to bicycle more, with almost twice as many rare cyclists choosing separated bike facilities over more facilities in general. The findings also suggested that the presence of bicycle facilities increased respondents’ comfort and willingness to try bicycling on a roadway. Most respondents felt more comfortable bicycling on a roadway with any type of bike facility, and this preference was even stronger when the facility was separated from drivers by any physical barrier. Separation was even more important when considering bicycling with children. Respondents also indicated that their comfort level increased while driving with greater separation from bicyclists.

A study by Li et al. found that physical environments can influence bicyclists’ perceptions of comfort on separated and on-street bicycle facilities (14). Their investigation, conducted in Nanjing, China, found that physical environmental factors significantly influenced bicyclists’ perception of comfort on the two types of facilities. Comfort was mainly influenced by the road geometry and surrounding conditions, such as the width of a path, presence of a slope, presence of a bus stop, physical separation from pedestrians, surrounding land use, and bicycle flow rate. For on-street bicycle facilities, comfort was influenced by factors including the width of the bicycle lane, the width of the curb lane, the presence of a slope, the presence of a bus stop, the amount of occupied car parking spaces, the bicycle flow rate, the motor vehicle flow rate, and the rate of use of electric bicycles. The researchers also found that physically separated paths provided greater comfort when there was light bicycle traffic and when there was traffic congestion on the street, while on-street bicycle lanes were preferred when bicycle volume was heavy.

A study by DuBose also found that separated bikeways encouraged more people to bicycle (15). Many people do not bicycle because they have safety concerns. Therefore, installing separated bikeways can improve bicyclist comfort while also helping reduce collision rates as drivers come to expect encounters with bicyclists more regularly.

A study by Huybers et al. (16) found that pavement markings and signs can reduce pedestrian casualties and injuries. They performed two experiments. In Experiment 1, use of a “yield here to pedestrians” sign alone reduced pedestrian/motor vehicle conflicts and increased motorists’

yielding distance. The results of Experiment 1 indicated that the addition of advance yield pavement markings was associated with a further decrease in conflicts and a further increase in motorist yielding distance. These results rule out the possibility that the lack of effectiveness of the yellow-green sign was due to a floor effect for conflicts or a possible ceiling effect for yielding farther behind the crosswalks. The results also suggest that signs made with yellow-green sheeting may be more easily recognizable and that it is possible that the motorists were attending more to the fluorescent yellow-green sheeting than to the message of the sign that was printed on it. Use of fluorescent yellow-green sheeting as the background of the sign did not help increase the effectiveness of the sign. In Experiment 2, the researchers used advance yield pavement markings alone and found that doing so was as effective at reducing pedestrian/motor vehicle conflicts and increasing yielding distance as the combination of a sign and pavement markings. The researchers suggested that the pavement markings were the essential component for reducing conflicts and increasing yielding distance.

A study by McNeil et al. (17) suggested that buffered and protected bike lanes can increase people’s sense of safety and comfort when bicycling. The project used data collected from surveys for a multicity study of newly constructed protected bike lanes. Participants were current bicyclists and residents who were potential bicyclists. The bicyclists agreed that buffers made them feel safer, and residents strongly believed that buffers effectively separated and protected bikes from vehicles, thereby increasing safety when bicycling. These findings suggest that bike lanes with an extra buffered space can increase the safety and comfort of bicycling for both current and potential bicyclists, which would make people more likely to ride a bicycle for transportation. The findings also suggest that both current bicyclists and potential bicyclists would feel comfortable riding on a busy commercial street if there were a bike lane with a physical barrier.

Review of Use of Vegetation Control

Various concepts for the multifunctional barrier system developed under this project incorporated different elements on the field side of the barrier to accommodate pedestrians (including those with disabilities) and bicyclists. These added elements can make cutting or trimming vegetation around the barrier more time consuming, which can increase both the cost and the safety risk associated with vegetation maintenance. Use of vegetation control was, therefore, a design element considered during the development of the new barrier system. Vegetation control can reduce maintenance costs and risk to workers associated with hand mowing or trimming around a barrier. Literature pertaining to the use of vegetation control for barrier systems is presented in the sections below.

Caltrans Roadside Management Toolbox

The Caltrans [California Department of Transportation] Roadside Management Toolbox is a web-based decision-making tool designed to improve the safety and maintainability of transportation projects (18). The management, maintenance, and control of vegetation on roadsides has become increasingly difficult as the miles of roadway and acres of roadside have increased while maintenance resources decreased. Historical methods of vegetation control (manual, mechanical, and chemical) have been sharply curtailed due to local development, increased traffic volumes, public concerns, and other economic and environmental issues.

The toolbox includes treatments composed of both materials familiar to traditional highway construction contractors (such as asphalt concrete, portland cement concrete, and road base), as well as less conventional materials or products (such as polyurea coatings, rubber mats, and fiber weed control mats). Figure 12 shows examples of vegetation control recommended by Caltrans.

Evaluation of DuroTrim Vegetation Control Mats

Dunn investigated the performance of DuroTrim Vegetation Control Mats for eliminating trimming around roadside delineator and guardrail posts and weighed the cost of purchasing and placing the mats versus hand trimming (19). Dunn found that the DuroTrim Vegetation Control Mats would be required to perform well for 9 to 21 years, on average, in order to recoup the cost of installation. This calculation includes the durability of the product, but not the cost of repair due to traffic damage, snowplow and wing damage, or damage caused by mowing operations.

DuroTrim Vegetation Control Mats are 2- × 2-ft tiles composed of shredded used tires bound together with a urethane resin binder. The manufacturer recommends use of two tiles per delineator post for a 4- × 2-ft mat. The mats weigh approximately 4.25 lb/ft2 and are connected and sealed at the joints with a one-part urethane adhesive. Figure 13 shows DuroTrim Vegetation Control Mats before and after a vehicle collision.

The use of the weed control mats could be justified in areas that are dangerous to maintenance workers, such as guardrail installations in high traffic areas. Because the delineator posts are farther from the edge of the traveled roadway, the risk to the maintenance workforce while hand trimming is reduced.

Because the DuroTrim Vegetation Control Mats appear to have performed adequately in the field trial, they could be considered for use where safety conditions warrant. That use should be limited, however, given the considerable initial cost. Applications should be limited to instances where the use of the mats would have a significant impact on the safety of roadside maintenance workers. The cost savings from elimination of trimming and mowing alone are not enough to justify the use of these mats in most situations.

Vegetation Management Under Guardrail for North Carolina Roads

Yelverton and Gannon (20) designed and then determined the influence of herbicides and plant growth regulators on the establishment of centipede grass, evaluated treatments for vegetation management under guardrails, and determined whether nitrogen fertility levels affected the establishment of centipede grass sod. They conducted experiments to attempt to correlate centipede grass and zoysia grass problem areas with geographical areas or soil parameters as well as to compare the establishment of common centipede grass and El Toro zoysia grass from sod simulating vegetation under a guardrail.

The researchers also determined management plans for these areas where centipede grass or zoysia grass was sodded into existing vegetation. Management plans included tolerance of herbicides and plant growth regulators as well as practices to transition the roadside to centipede grass or zoysia grass in an effort to achieve a monoculture turfgrass stand. The experiments included the tolerance of centipede grass to herbicides and plant growth regulators applied at seeding and soon thereafter, the survival of centipede grass when subjected to various fertility regimes, and the establishment of zoysia grass versus centipede grass from sod under roadside conditions.

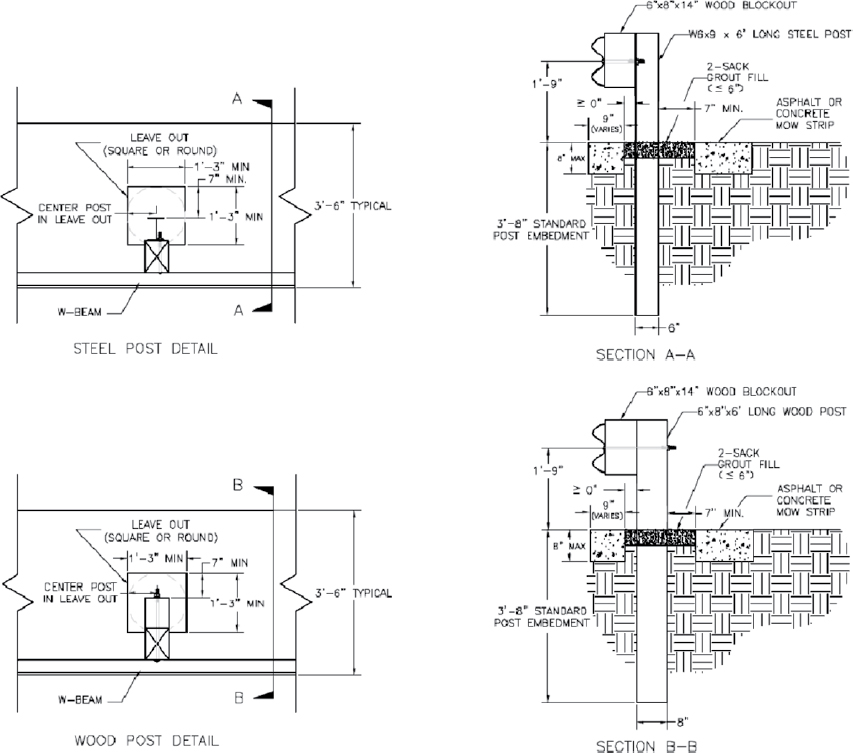

Dynamic Response of Guardrail Systems Encased in Mow Strips

Bligh et al. examined the effect of pavement post encasement on the crashworthiness of strong post guardrail systems (21). The performance of these systems used experimental testing and numerical simulation. Seventeen configurations of wood and steel guardrail posts embedded in various mow strip systems and confinement conditions were subjected to dynamic impact testing with a bogie vehicle. Along with enhanced impact performance, it was suggested that mow strip configurations featuring leave-outs were also more practical, on the basis of ease of repair after an impact. Crash tests of a steel post guardrail system and wood post guardrail system encased in a selected concrete mow strip with low-strength grout-filled leave-outs were successful. While the number of full-scale tests conducted was limited, the structure of subcomponent analysis and testing provided additional insight into the performance of guardrail posts encased in a mow strip.

Recommendations regarding the acceptable ranges for some key mow strip parameters, such as mow strip material and dimensions, leave-out dimensions, leave-out backfill material, and guardrail post location were provided as part of this study.

Evaluation of Tire-Rubber Antivegetation Tiles

Raine conducted a project to allow TxDOT to evaluate the ease of installation, cost, and effectiveness of antivegetation tiles made from recycled tires (22). The purpose of the project was to evaluate the ease and cost of installing antivegetation tiles made from recycled tires to control vegetation around guardrails and signposts. The project also compared the tiles’ effectiveness and life-cycle costs with those of other TxDOT-approved designs, such as using grout or concrete installed around guardrail posts or signposts. If tire-rubber tiles for guardrail and signposts are eventually accepted for use in new construction, retrofits, and maintenance to control vegetation, more than 500,000 tires worth of scrap tire rubber that is generated in Texas each year could be consumed.

Alternatives to Labor-Intensive Tasks in Roadside Vegetation Maintenance

Arsenault et al. addressed herbicide use and the feasibility of replacing herbicides with alternative mechanical vegetation control technologies (23). The use of hot foam application, radiant heating, and high-pressure water application was compared with the use of mowing and herbicide application in the maintenance of areas around posts and guardrails, mow strips, and paved surfaces. The reduction of herbicides was important because Caltrans had mandated that herbicide use be reduced to 80% of 1994 levels by 2012.

According to the report, the current major vegetation control methods included (a) herbicide application, (b) mechanical mowing, and (c) no vegetation maintenance. The alternative vegetation control technologies included the following:

- Hot water, hot foam, steam application: The hot water melts the waxy coating of the vegetation, leading to severe dehydration (Figure 14).

- Hydromechanical obliteration: High-pressure application of water is used to cut/mow vegetation. When held at a distance of 1 m (3 ft), the nozzle clears most brush without disturbing the soil.

- Thermal weed treatments: Open flames or radiant heat or ultraviolet heat are used to control weeds (Figure 15).

The benefits and drawbacks of each method are discussed in the report in detail, along with the cost calculations for roadside application.

The report also includes recommendations on the combination of alternative and current technologies. A combination of two or more methods may lead to the development of more-effective and efficient control methods. In this way, some of the vegetation control technologies, when combined, will perform better than each respective technology alone. The combination options are (a) hot foam and radiant heat, (b) hot foam and mowing, and (c) hot foam and other attachments for the Advanced Roadway Debris Vacuum (ARDVAC).

Alternative Design of Guardrail Posts in Asphalt or Concrete

Arrington et al. focused on testing alternative materials for the leave-out sections around guardrail posts encased in a pavement mow strip (24). Figure 16 shows the tested guardrail posts

in mow strips. A two-sack grout mixture that had been successfully crash tested previously was used as a baseline reference for acceptable impact performance. Static laboratory and dynamic bogie impact testing was conducted to evaluate the various products. The long-term durability of these products was not evaluated.

The products that were investigated included a two-part urethane foam, a molded rubber product that had an insert fabricated to match the size of the leave-out, a flat recycled rubber mat that rested on top of a leave-out backfilled with soil, and a new pop-out concrete wedge.

All of the products except the flat rubber mat were considered to have acceptable impact performance. The acceleration levels associated with the flat rubber mat significantly exceeded the baseline threshold established from the test results of the two-sack grout mixture. The soil confined within the leave-out was responsible for the high acceleration. Since the soil was compressed between the post and the back face of the leave-out, without any void space, the added height and confinement of the soil led to the high acceleration levels.

The other tested products were considered to be acceptable alternatives to the two-sack grout mix from the standpoint of impact performance and vegetation control. However, the advantages and disadvantages regarding cost, availability, and ease of installation and inspection should be considered before selecting the product.

Assessment of Alternatives in Vegetation Management at Pavement Edge

Willard et al. documented findings from case studies at 43 locations throughout the state of Washington that compared and contrasted vegetation management alternatives at the pavement edge (25). The traditional Washington State DOT practice of maintaining a bare ground strip at the pavement edge was being reevaluated as a result of concerns about potential effects to the environment from these types of herbicide applications and because satisfactory results could be achieved without the use of herbicides at many locations. This study implemented strategies to either establish and maintain vegetation up to the pavement edge or maintain a bare strip of ground through nonchemical methods.

Alternative approaches were grouped into five categories: managed vegetation up to the edge of the pavement, pavement edge design, cultivation, weed barriers, and nonselective herbicides. The set of alternatives studied in the category of managed vegetation up to the edge of pavement was the most extensive group of experiments. This alternative focused on establishing desirable vegetation (grasses) on the nonpaved shoulder and maintenance with selective chemical and/or mechanical means (mowing and grading) in a variety of situations.

The category of pavement edge design included two locations where some form of paved break/ edge drop was already present or constructed at the edge of the paved shoulder. The category of cultivation included situations in which a band 2 to 3 ft wide was annually turned and repacked with a tractor-mounted disking tool followed by a grader. The category of weed barriers tested a series of products/materials designed as soil cover/matting material for use under a guardrail. The category of nonselective herbicides evaluated annual treatment of a 2- to 4-ft band with various mixtures of nonselective, pre- and postemergent herbicides each spring.

The first two categories focused on a vegetative treatment at the pavement edge, while the last three described various methods of providing a nonvegetative pavement edge. Both of these conditions are now referred to as a “Zone 1” treatment.

Evaluation of alternatives was based on a comparison of costs and results. Maintenance costs were averaged per mile and per year, since some activities might occur more or less than once

per year. Results included impacts on maintenance objectives such as traffic safety, worker safety, environmental factors, and preservation of pavement and roadside hardware.

The results varied significantly between eastern and western Washington, in part due to precipitation and vegetative growth. In eastern Washington, particularly in the more arid areas, it was found that desirable grasses could be established up to the edge of the pavement. This was accomplished either through soil preparation and planting with new construction or through efforts by maintenance to manage the transition from bare ground shoulders to naturally occurring grasses over a series of years. In cases where desirable grasses were successfully established, there were no adverse impacts on maintenance objectives, and the level of effort and cost to maintenance was shown to decrease over time.

In western Washington, where the climate promotes more vegetative growth, there was a corresponding increase in required maintenance resulting from impacts on traffic safety and stormwater management. Where tall grasses blocked sight distance at intersections and curves in the spring and early summer, increased mowing was required at a greater cost than if these areas had been maintained with a vegetation-free pavement edge. In locations where stormwater flowed to the edge of the pavement, it was found that the presence of grass at the pavement edge resulted in a buildup of soil and debris and subsequent problems related to standing water on the roadway shoulder. Over the course of the study period, a number of maintenance innovations were proven effective in removing edge buildup and improving the efficiency of mowing operations. However, in the majority of cases in western Washington where vegetation was allowed to grow at the edge of the pavement, there was an increased cost and level of effort compared with the use of herbicides to maintain a vegetation-free pavement edge.

Information supports the continued or renewed application of residual herbicides at the pavement edge in certain locations, such as under guardrails and on western Washington highways with narrow paved shoulders and abundant vegetative growth. In some areas where shoulders were allowed to grow vegetation, bare-ground treatments were to be reestablished with a narrow (2- to 3-ft) strip at the edge of the pavement. In areas with unique environmental constraints, or where it had proven effective to manage the pavement edge with mowing, grading, sweeping, or other routine maintenance practices, those practices were to be continued. In eastern Washington, areas would continue to minimize and phase out bare-ground pavement edge strips as appropriate.

Guardrail Vegetation Management in Delaware

To explore alternatives to traditional herbicide treatments under guardrails, Barton and Budischak evaluated the following (26):

- Three herbicide formulations:

- Formulation 1: Standard Delaware DOT New Castle County Formulation composed of DuPont® Karmex® DF Herbicide (diuron), BASF Plateau (imazapic ammonium salt), Dow AgroSciences Accord® XRT (glyphosate), and BASF Pendulum (pendimethalin).

- Formulation 2: Sensitive areas formulation composed of BASF Plateau (imazapic ammonium salt), Dow AgroSciences Accord® XRT (glyphosate), and BASF Pendulum (pendimethalin).

- Formulation 3: Dow AgroSciences Accord® XRT (glyphosate).

-

Four weed control barriers:

- U-Teck™ WeedEnder standard installation (a permeable recycled fiber material).

- U-Teck™ WeedEnder custom installation (a product designed to reach the road edge and accommodate variances in post width).

- Universal Weed Cover (a semirigid panel made of 100% recycled plastic.

- TrafFix (a rubber mat with three punched guardrail cutouts for flexible installation).

- Competitive vegetation:

- Low fescue: difficult to establish reliably under guardrail but, when established, provided a desirable uniform cover with minimal maintenance.

- Zoysia seed: not established from seed during the first growing season.

- Zoysia sod: established successfully and almost entirely eliminated weeds under the guardrail and required no trimming during the first year.

- FlightTurf: only established at the end of the 2012 growing season.

- Hand trimming: Hand trimming was required once or twice per year depending on the site, weather, and timing.

- Pavement under guardrail: When conducted once per year, hand trimming was the most cost-effective treatment and provided a green mat of vegetation below the guardrail.

Crash Tests on Guardrail System Embedded in Asphalt Vegetation Barriers

The Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) authorized tests to be performed on guardrails installed in accordance with GDOT Standard Detail S-4-2002, which was used in Georgia prior to 2017 and includes an asphalt mow strip with nearby curb (27). The University of Nebraska’s MwRSF was selected to perform the tests in accordance with AASHTO’s MASH. Test Vehicle 1100C, a small passenger car, was used to perform a single crash test. The crash test results exceeded multiple MASH safety evaluation criteria, including occupant compartment deformation, windshield crushing, and maximum allowable occupant ridedown acceleration. Thus, the Midwest Guardrail System (MGS) installed in an asphalt mow strip with a curb placed behind the barrier was deemed to be unacceptable, according to the TL-3 safety performance criteria for Test 3-10 provided in MASH.

GDOT no longer uses the S-4-2002 mow strip configuration. Beginning March 15, 2017, GDOT directed that all new guardrail construction projects on Georgia roadways use asphalt layers that are paved up to the face of the post, leaving the post itself and the area behind unrestrained. Figure 18 shows the actual test bed site behind posts.

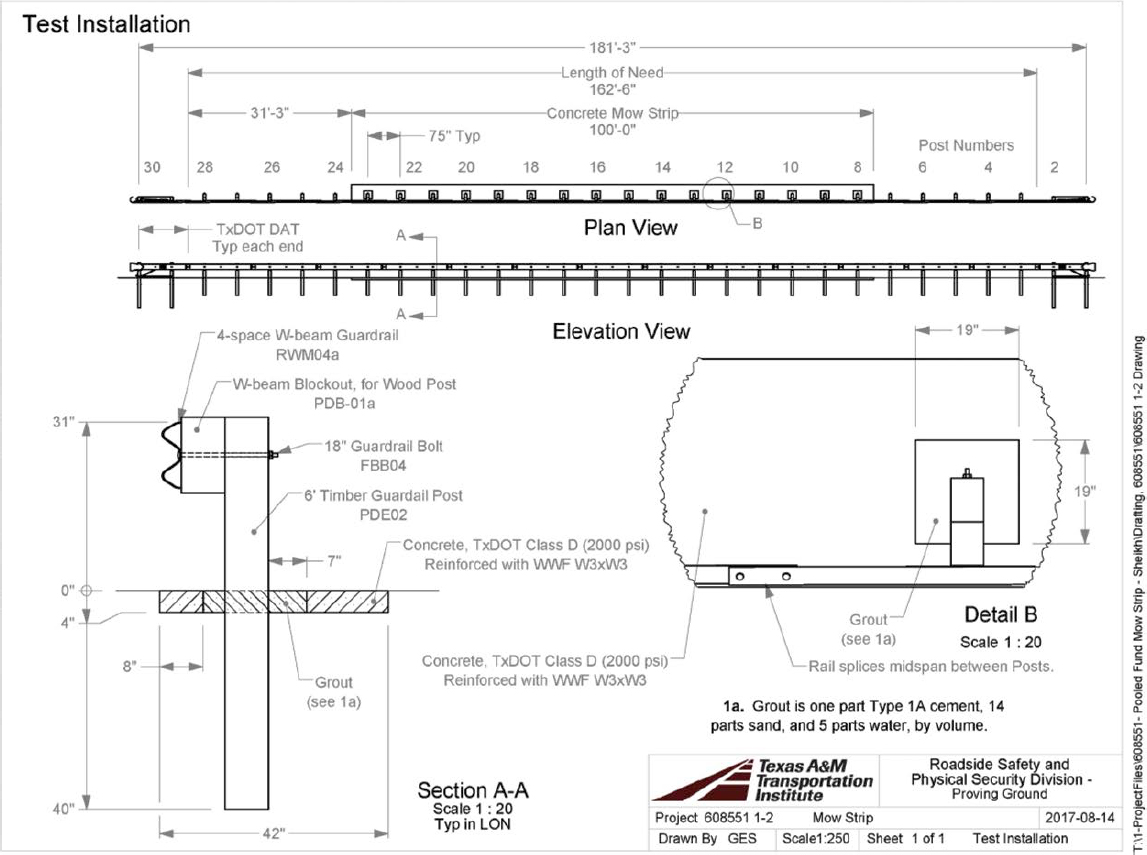

MASH Evaluation of 31-in. W-Beam Guardrail with Wood and Steel Posts in Concrete Mow Strip

The performance of a 31-in.-tall W-beam guardrail system installed in a concrete mow strip with wood and steel posts, respectively, was evaluated (28). Figure 19 shows the system details. The presence of a mow strip prevents growth of vegetation around the posts, and thus helps

reduce maintenance for the guardrail system. MASH Tests 3-10 and 3-11 were performed for both wood and steel guardrail systems.

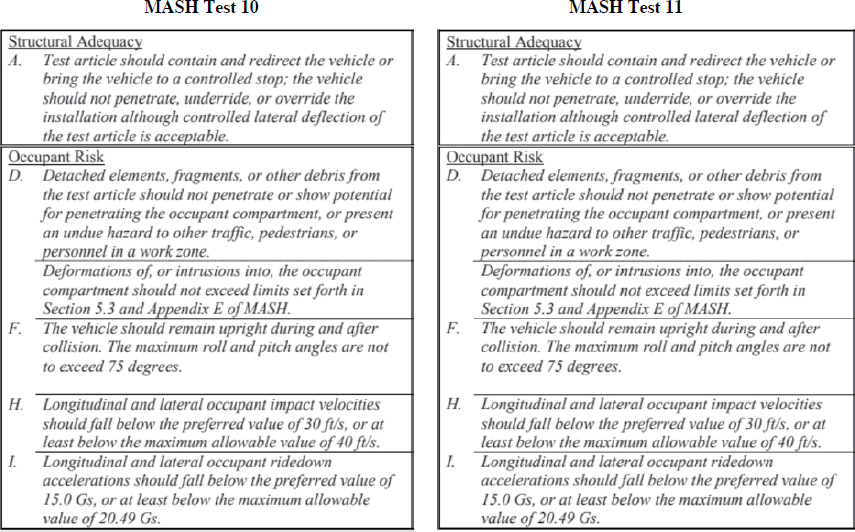

Review of MASH Testing Standards

MASH Testing Standards

AASHTO’s MASH (1) is the latest in a series of documents that provide guidance on testing and evaluation of roadside safety features. This document was initially published in 2009 and represents a comprehensive update to crash test and evaluation procedures to reflect changes in the vehicle fleet, operating conditions, and roadside safety knowledge and technology. It superseded NCHRP Report 350: Recommended Procedures for the Safety Performance Evaluation of Highway Features (29).

MASH was developed to incorporate significant changes and additions to the procedures for the safety performance of roadside safety hardware, including new design vehicles that better reflected the changing character of vehicles using the highway network. Like NCHRP Report 350, MASH defines six test levels for longitudinal barriers (the type of barrier designed/investigated through this project). Each test level places an increasing level of demand on the structural capacity of a barrier system.

MASH Test Level 2 (TL-2) is recommended for investigating the behavior of roadside safety hardware (including longitudinal barriers) when impacted by passenger vehicles to evaluate the placement of such roadside safety hardware on low-speed roadways. MASH recommends two tests for evaluating longitudinal barriers according to TL-2:

- MASH Test 2-10: 2,240-lb vehicle impacting the length of need (LON) section at a speed of 44 mi/h and an angle of 25 deg.

- MASH Test 2-11: 5,000-lb pickup truck impacting the LON section at a speed of 44 mi/h and an angle of 25 deg.

MASH TL-3 is recommended for investigating the behavior of roadside safety hardware (including longitudinal barriers) when impacted by passenger vehicles to evaluate the placement of such roadside safety hardware on high-speed roadways. MASH recommends two tests for evaluating longitudinal barriers according to TL-3:

- MASH Test 3-10: 2,240-lb vehicle impacting the LON section at a speed of 62 mi/h and an angle of 25 deg.

- MASH Test 3-11: 5,000-lb pickup truck impacting the LON section at a speed of 62 mi/h and an angle of 25 deg.

Due to higher impact energy, Test 3-11 results in greater lateral deflection and helps evaluate connection strength and the tendency of the barriers to rotate. Test 3-10 is needed to evaluate occupant risk and potential for vehicle snagging and occupant compartment intrusion.

The target critical impact point (CIP) for each test is determined according to information provided in MASH and is revised through computer simulations and engineering analysis to help support the decision on the proposed CIPs.

According to the MASH standards, the impact performance of tested roadside safety systems is judged on the basis of the following factors:

- Structural adequacy, which is judged on the ability of the system to contain and redirect the vehicle.

- Risk of occupant compartment deformation or intrusion by detached elements, fragments, or other debris from the test article, which evaluates the potential risk of hazard to occupants and, to some extent, other traffic, pedestrians, or workers in construction zones, if applicable.

- Occupant risk values, for which longitudinal and lateral occupant impact velocity and ridedown accelerations for the 1100C and 2270P test vehicles must be within the limits specified in MASH and which determine the risk of injury to the occupants.

Table 6. Safety evaluation criteria for full-scale crash testing (1).

|

- Postimpact vehicle trajectory, which considers the potential for secondary impact with other vehicles or fixed objects creating further risk of injury to occupants of the impacting vehicle and/or the risk of injury to occupants in other vehicles.

Table 6 shows the safety evaluation criteria from Table 5-1 of MASH, which are used to evaluate the full-scale crash tests (1).

MASH Implementation Plan

The AASHTO Technical Committee on Roadside Safety and FHWA adopted a new MASH implementation plan that has compliance dates for installing MASH hardware that differ by hardware category. After December 31, 2019, all new installations of roadside safety devices on the National Highway System must have been successfully evaluated according to the 2016 edition of MASH. FHWA no longer issues eligibility letters for highway safety hardware that has not been successfully evaluated to MASH performance criteria.