Effects of Ionizing Radiation: Atomic Bomb Survivors and Their Children (1945-1995) (1998)

Chapter: 10 Studies on the Genetic Effects of the Atomic Bombs: Past, Present, and Future

10

Studies on the Genetic Effects of the Atomic Bombs: Past, Present, and Future

JAMES V. NEEL, JUN-ICHI ASAKAWA, RORK KUICK SAMIR M. HANASH, AND CHIYOKO SATOH

Summary

The results of some 48 years of studies on the potential genetic effects of the atomic bombs are reviewed. There are no statistically significant differences between the children of the exposed survivors and a suitable comparison group of children with respect to frequency of congenital defects, sex ratio, survival, cancer, growth and development, cytological abnormality, and mutation affecting a variety of biological markers. However, there is a small deviation in the direction of a genetic effect, and this is used to develop an estimate of the mutational doubling dose of acute ionizing radiation of between 1.7 and 2.2 Sv equivalents. It is suggested that a review of the mouse data on the genetic effects of radiation is in satisfactory agreement with this estimate. Possible future studies at the DNA level on immortalized cell lines are discussed. The possibility that an increase in tumors of all types can be used as a ''pit canary" for genetic damage is also discussed.

Introduction

This program provides an unusual opportunity not only to review the past studies at Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission/Radiation Effects Research Foundation (ABCC/RERF) on the genetic effects of the atomic bombs, but also to consider what, if any, future studies are indicated, and I shall attempt to do both. Past

studies to be summarized are the work of many minds and hands, all recognized in our various publications. It is impractical in this brief presentation to mention the names of all investigators with significant involvement over the past 48 years as I proceed, but I note especially the major role Jack Schull has played in these studies. I will also in this presentation mention some recent unpublished work and calculations, and note that my co-authors on this paper are Dr. J. Asakawa, Dr. C. Satoh, Mr. R. Kuick, and Dr. S. Hanash.

Brief Summary Of Past Studies On The Genetic Effects Of Atomic Bombs

The genetic studies of the children of survivors of the atomic bombings have been summarized several times in the past five years (Neel et al., 1990; Neel and Schull, 1991; Neel, 1995), and I propose to be very brief in the present summary. As of now, the reproductive performance of atomic bomb survivors living in Hiroshima and Nagasaki is complete. Most of the studies to be mentioned have been based on a cohort (or subset thereof) consisting of 31,150 children born to parents one or both of whom were within 2,000 meters of the hypocenter at the time of the bombing (ATB) and a matched comparison cohort of 41,066 children born to survivors beyond this distance, or to parents now living in either city but not there ATB. Over the years, data have been collected on these children (F1) concerning untoward pregnancy outcomes (major congenital malformation and/or stillbirth and/or neonatal death); sex of child; malignant tumors with onset prior to age 20; death of liveborn infants through an average life expectancy of 26.2 years, exclusive of death from malignancy; growth and development of liveborn infants; cytogenetic abnormalities; and mutations altering the electrophoretic behavior or function of a selected battery of erythrocyte and blood plasma proteins. Most of the parents have been assigned radiation exposures based on the DS86 schedule; where this was impossible, DS86-type doses have been approximated. All of the data have been analyzed on the basis of these exposures. In a series of analyses that involved fitting a linear dose-response regression model to the occurrence of the various indicators of radiation damage, the model including up to six concomitant variables depending on the indicators in question, there was no statistically significant effect of combined parental exposure on any of these indicators. I wish to emphasize that, relatively limited though our knowledge of mammalian radiation genetics was in 1947, this possible outcome was anticipated (Genetics Conference, 1947), but the decision was made to proceed nevertheless with what has become the largest study in genetic epidemiology ever undertaken on the basis that, whatever the outcome, it was of profound interest.

In the planning stages of the study, inasmuch as most births were midwife-attended home deliveries, we were gravely concerned over the possibility of concealment of congenital abnormalities, since such births, in a society with open koseki records, might be concealed because they might stigmatize the family. We

went to great pains to enlist the cooperation of the midwives and obstetricians, who readily grasped the significance of the study. The attendant at delivery was urged to report at once any abnormality, whereupon a physician employed by ABCC examined the baby as soon as possible; in any event, all newborns were examined by an ABCC physician within two or three weeks of birth, and a 30% sample reexamined at approximately nine months of age. For what it is worth, the data on congenital defects in the children of unexposed parents were very similar to world figures (Neel, 1958). This clinical program was terminated in 1953.

A fact that we believe went far to ensure the quality of the data was that for some years after the end of WWII, the Japanese government maintained the wartime system of special rations for Japanese women who registered their pregnancies at the completion of the fifth lunar month. By incorporating a registration for the genetic studies into this ration system, we had the basis for a prospective study of pregnancy outcomes, an aspect of the study design whose importance we cannot overemphasize. The registrations for the genetic studies were initiated in March 1948; these children would have been conceived in October 1947. There is thus a hiatus of some two years between the bombings and the first direct collection of data (but births in those first two years were incorporated into certain of the study groups).

A convenient metric for measuring the genetic effects of ionizing radiation is the estimated dose of radiation necessary to equal the impact of spontaneous mutation on the indicator in question, i.e., the doubling dose. If we assume that despite the absence of a statistically significant regression of any of the indicators on parental exposure, the regressions that were derived are nonetheless the best current indicators of the genetic effects of radiation on humans, then these regressions can be employed to generate a doubling dose. In order to make such an estimate, one must have an estimate of the contribution of spontaneous mutation in the parents to each of the indicators. This is sometimes relatively easy; sometimes, as in the case of major congenital defect, it is more difficult. Also, the estimate is restricted to the effects of the mutation of single genes with discrete effects. Thus, it was not useful to calculate a doubling dose for such indicators as physical growth and development and the sex ratio (although neither of these yielded findings suggestive of a radiation effect). For the remaining five indicators, the findings were as shown in Table 10.1. Since all the regressions evaluate the effects of essentially non-overlapping indicators (i.e., those that are independent of each other) and are based on the same cohorts or subsets thereof, it is legitimate to combine these additively. The sum of the five individual regressions is 0.00375/Sv equivalent, with a considerable but difficult-to-define error. We estimated, as shown in Table 10.1, that in each generation of newborns, something like 6.3 to 8.4 infants per 1,000 would ultimately exhibit some one of these five indicators because of mutation in the parental generation. The estimate of the doubling dose thus falls between 0.00632 and 0.00375 Sv equivalents and 0.00835 and 0.00375 Sv equivalents, or 1.68 to 2.22 Sv equivalents, with a poorly defined error term.

TABLE 10.1 A summary of the regression of the various indicators on parental radiation exposure and the impact of spontaneous mutation on the indicator, after Neel et al. (1990).

|

Trait |

Regression coefficient, β, for combined parental dose (Sv) |

s.e.(β,) |

Contribution of spontaneous mutation |

|

UPO |

+0.00264 |

±0.00277 |

|

|

F1 mortality |

+0.00076 |

±0.00154 |

0.0033-0.0053 |

|

Protein mutations |

-0.00001 |

±0.00001 |

|

|

Sex-chromosome aneuploids |

+0.00044 |

±0.00069 |

0.0030 |

|

F1 cancer |

-0.00008 |

±0.00028 |

0.00002-0.00005 |

|

Total |

0.00375 |

|

0.00632-0.00835 |

Most of the gonadal ionizing radiation humans will experience will be low-level, chronic, or intermittent, rather than the acute (single dose), relatively high exposures of the atomic bombs. I say "relatively" because the average gonadal dose for both parents combined varied in the various different studies between 0.32 and 0.60 Sv equivalents; in the calculation of these doses the relatively low neutron component was assigned a relative biological effectiveness (RBE) of 20. In the mouse experiments, the gonadal doses were usually 3.0 or 6.0 Gy. Acute radiation at relatively high doses is on a per-unit basis genetically more mutagenic than chronic radiation, the dose-rate factor ranging from 3 to 10, depending on the precise indicator. The best studied system in mice, the Russell 7-locus test, yielded one of the lowest dose-rate factors, a factor of 3. Because of the linear-quadratic nature of the radiation dose-genetic damage curve, we suggest that the dose-rate factor to be used in extrapolating from the effects of acute too chronic radiation on the basis of the Japanese data should be 2, so that the doubling dose for low-level chronic ionizing radiation in humans becomes 3.4 to 4.4 Sv equivalents.

A Comparison Of The Findings In Hiroshima-Nagasaki With Studies Of The Genetic Effects Of Ionizing Radiation On Mice

This doubling dose estimate for humans is substantially higher than the extrapolation to humans from the results of experiments on mice that dominated thinking about genetic risks from approximately 1950 to 1985. The figure most often quoted for acute radiation was about 0.4 Gy. Accordingly, in 1989, together with Susan Lewis (Neel and Lewis, 1990), I undertook a review of the accumulated data on

mouse radiation genetics, including deriving, for each indicator that had been studied, an estimate of the doubling dose. The results with respect to specific locus tests are shown in Table 10.2. Note the wide range in the various estimates, to which we found it impossible to attach errors in the usual statistical sense. Not shown there (because the data do not lend themselves to the calculation of a doubling dose) are the important results of Roderick (1983), who estimated for mice a recessive lethal mutation rate in post-spermatogonial cells per locus from ionizing radiation of only 0.35 × 10-8/0.01 Gy, whereas for the Russell 7-locus system, the corresponding rate for all mutations was 45.32 × 10-8/0.01 Gy, approximately 80% of these mutations being homozygous lethal. As Roderick pointed out, this was about one hundredfold difference, although the error term to be attached to his estimate was large but difficult to calculate. The simple average of all the estimates in Table 10.2, unweighted because we could think of no good way to weight the individual studies, was 1.35 Gy, with an indeterminate error. Given the relatively high doses at which the mouse experiments had been performed, we felt that in extrapolating to the effects of low-level, chronic, or small intermittent exposures, a dose-rate factor of 3 was appropriate (Russell et al., 1958). The estimate of the genetic doubling dose of chronic ionizing radiation thus became 4.05 Gy, in surprising agreement with the estimate for human exposures. But note that the estimate for mice is gametic, whereas that for humans is zygotic.

TABLE 10.2 A summary of the various indicators of genetic radiation damage pursued in murine experiments and the doubling dose they yield (Neel and Lewis, 1990).

|

|

In retrospect, it is instructive to consider why the results of the Russell system so dominated the thinking of 20 and 30 years ago. It was a simple system yielding clear-cut results for which a great deal of data became available. When other studies suggested lesser genetic effects of ionizing radiation, the results were often dismissed as reflecting the use of "less sensitive" systems. Furthermore, the desire to be conservative in risk setting led to reliance on the systems that yielded the most striking results. However, I suggest that—for reasons Russell could not know at the time, and which will now be enumerated—the loci he selected probably had higher spontaneous and induced mutation rates than the average locus.

Russell in his very first papers recognized that the key assumption was that his loci were representative of the genome. There are now data for the mouse indicating a sevenfold range in the rate per locus with which spontaneous mutation results in phenotypic effects (Green et al., 1965; Schlager and Dickie, 1967). With respect to humans, Chakraborty and Neel (1989) have suggested from population data a tenfold range in the spontaneous mutability of human genes. In Russell's data, radiation produced 18 times more mutations at the s locus than at the a locus, surely a signal to extrapolate with caution (reviewed in Searle, 1974). Finally, in a somatic cell mutagenization experiment in our laboratory, utilizing the TK6 line of human lymphocytoid cells and employing ethylnitrosourea as mutagen, the protein products of 263 loci were scored for the occurrence of mutants resulting in electrophoretic variants, employing a two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel system (Hanash et al., 1988). Ten of the 263 loci whose protein products were being scored were known to be associated with genetic polymorphisms, on the basis of family-oriented studies on gels derived from human peripheral lymphocytes. The induced mutation rate at these 10 loci was 3.6 times greater than at the monomorphic loci, an observation with a probability <0.004. The relevance of all these observations to the possible bias in the Russell system is that to set the system up, Russell drew on loci characterized by genetic variation. There had to be at least two alleles known for each of the loci in his system, and it helped in creating the optimum phenotype for scoring if there were even more alleles available to choose among. This use of loci for which variants were readily available introduced the bias.

There is an additional reason why the previous extrapolation from mouse to man was conservative. The mouse doubling-dose estimate was male based. The demonstration (Russell, 1965) that although in the first few litters post-treatment the offspring of radiated female mice exhibited about the same amount of genetic damage as the offspring of radiated males, there was no apparent damage in the later litters of these females, created a dilemma for risk setting. Was the human female similar to the mouse female in this respect? The estimates of Table 10.2 are male based. To be conservative, in extrapolating to the human situation, the mouse male-derived risks were applied to both sexes. In the Japanese data, however, radiated females contribute about half the dose.

As a result of the studies on the genetic effects of the A-bombs, plus this evaluation of the totality of the murine data, the case for a major revision downward

in the previous estimates of the genetic risks of radiation for humans must be very seriously considered.

Some Current Uses Of The Results Of The Abcc/Rerf Genetic Studies

The results of studies on radiation-induced oncogenesis at RERF have provided worldwide standards. The results of the genetic studies are beginning to do likewise. Without doubt, the most spectacular use of these data has been in connection with the suit brought against British Nuclear Fuel, with respect to the allegation that the "hot spot" for childhood leukemia in Seascale, West Cumbria, England, was related to the employment of four of the fathers of these children in the nearby Sellafield Nuclear Reprocessing Facility, i.e., that the high number of cases was a result of leukemogenic germ-line mutations induced in these fathers (Gardner et al., 1987). The radiation received by the fathers in question was well within the occupational guidelines, i.e., no father over a working period of 6-13 years received more than an estimated total exposure of 200 mSv. Thus, in effect this legal action, which became the most expensive civil suit in the history of the English courts, was a challenge to existing guidelines. The data on leukemia in the F1 of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, including a subset of the data on malignancy in the F1 (Yoshimoto et al., 1990), became pivotal to the trial. A precise calculation is impossible, but to a first approximation a genetic interpretation of the Seascale leukemia cluster implied genetic sensitivities some 4,000 to 6,000 times greater than suggested by the Japanese data. The trial thus challenged existing genetic guidelines. I was amazed at the lengths to which plaintiff's counsel went to attempt to discredit the Japanese study in their efforts to legitimize their own case. In the end, the data emerged unscathed, and the judge found resoundingly for the defense. The study that precipitated this trial is probably the most egregious example of a false positive in genetic epidemiology on record (Neel, 1994a).

The analysis of the F1 data that we just summarized was not completed in time to figure strongly in the results of the BEIR V report but did receive prominent consideration in the most recent (1993) update of the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR), entitled, "Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation."

New Techniques For Evaluating The Genetic Effects Of Atomic Bombs

In the 1980s, it became apparent that the techniques of molecular genetics might be brought to bear on the question of the genetic effects of the bombs. Accordingly, in 1985, the RERF began the task of establishing cell lines appropriate to such studies, the goal being approximately 500 mother/father/child trios in which one or both parents had been exposed to the atomic bombs, and a similar set of comparison

constellations in which neither parent had been exposed. Where more than one child was available, he or she was included in the study, and the mean number of children per parental set was 1.45. The task of establishing the cell lines is almost completed. Meanwhile, the genetics staff launched on an exploration of the technologies that might be employed. To date, three systems utilizing the DNA approach have been piloted by RERF staff and their collaborators.

A DGGE System

The first of these employed the denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) technique of Myers et al. (1985) and Lerman et al. (1986) primarily in combination with other techniques to detect unknown single nucleotide substitutions (Hiyama et al., 1990; Takahashi et al., 1990; Satoh et al., 1993). In terms of nucleotides examined per unit of technician time, the most efficient of the several variations of this approach which were explored involved amplification of target sequences with PCR, digestion of these sequences to fragments of approximately 500 bp, followed by DGGE of the fragments (Satoh et al., 1993). A total of 6,724 bp were examined per individual, using the human coagulation factor IX gene as substrate. In this pilot study, samples from 63 couples and 100 of their children were examined. Half of the children were born to parents one or both of whom had been exposed to the atomic bombs. Eleven previously undescribed nucleotide substitutions were detected in the parents. No mutations were detected in the approximately 672,000 nucleotides examined in the 100 children in the study, not surprising in view of the estimated spontaneous mutation rate per nucleotide per generation of 1 × 10-8 (Neel et al., 1986). This technique is most efficient in the detection of nucleotide substitutions.

The Use of Minisatellites

The second approach, published under the authorship of Kodaira et al. (1995), concentrates on studying mutation that alters the length of minisatellite loci, also known as VNTR loci (Variable Number of Tandem Repeats). Employing Southern blot analysis of a battery of six minisatellites (Pc-1, 1![]() M-18, ChdTC-15, p

M-18, ChdTC-15, p![]() g3,

g3, ![]() MS-1, and CEB-1), the investigators identified 6 mutations in 390 alleles from 65 parents whose gametes represented an average exposure of 1.9 Sv equivalents, a mutation rate of 1.5%; and 22 mutations in 1,098 alleles of the 183 gametes from the unexposed parents, a mutation rate of 2.0%. The difference is not statistically significant and, in any event, in a direction opposite to hypothesis. The authors calculate that, given the observed spontaneous mutation rate and using standard power function statistics (a type I error of 0.05 and a type II error of 0.20), it would be necessary to survey two samples (exposed and unexposed) of 1,188 germ cells each to detect a significant difference at the 0.05 level. Certainly, given the need to extend our knowledge of the genetic effects of radiation, the series should be extended at least that far. Furthermore, given the general acceptance

MS-1, and CEB-1), the investigators identified 6 mutations in 390 alleles from 65 parents whose gametes represented an average exposure of 1.9 Sv equivalents, a mutation rate of 1.5%; and 22 mutations in 1,098 alleles of the 183 gametes from the unexposed parents, a mutation rate of 2.0%. The difference is not statistically significant and, in any event, in a direction opposite to hypothesis. The authors calculate that, given the observed spontaneous mutation rate and using standard power function statistics (a type I error of 0.05 and a type II error of 0.20), it would be necessary to survey two samples (exposed and unexposed) of 1,188 germ cells each to detect a significant difference at the 0.05 level. Certainly, given the need to extend our knowledge of the genetic effects of radiation, the series should be extended at least that far. Furthermore, given the general acceptance

of the fact that ionizing radiation produces mutations, even without a significant difference between the two datasets, these data, like the data from the previous studies, can be taken at face value and used to produce a doubling dose estimate for this phenomenon; but this can only be done if, unlike the present situation, there is an excess of mutations in the children of exposed parents. However, even if the present deficiency of mutations in the children of exposed parents were to persist in an expanded series, the data can be used, at stated probability levels, to place a lower limit on the doubling dose.

Because the function of these minisatellites is so poorly understood, they are not a very satisfactory marker of radiation damage for a public interested in the phenotypic impact of an increased mutation rate on its children. However, it occurred to me, in writing an invited editorial to accompany the paper of Kodaira et al. (Neel, 1995), that these studies might have a value that could not have been anticipated a few years ago. Since 1991, eleven diseases have been recognized for which the mutational basis is an increase in the numbers of a specific trinucleotide repeat embedded in the gene (reviewed in Ashley and Warren, 1995). Some of these are quite well-known causes of mutational morbidity (e.g., the fragile X syndrome, myotonic dystrophy, Huntington's chorea). The basic repeat unit in the minisatellites employed in the study of Kodaira et al. varies from 5 to 43 nucleotides. If mutation at these loci can be shown to follow the same principles as mutation affecting the length of minisatellites, then the latter may in the future serve as surrogates for the former.

Two-Dimensional DNA Gels

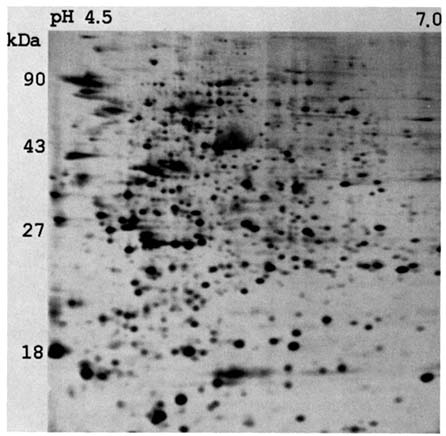

We come now to a third approach, in which our group in Ann Arbor has been collaborating with Dr. Asakawa of RERF. While RERF was establishing the cell lines, we in Ann Arbor devoted considerable effort to exploring the utility of two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of protein solutions in the study of mutation (Neel et al., 1984; Neel et al., 1989). Figure 10.1 illustrates a typical preparation based on peripheral lymphocytes, in which approximately 200 proteins can be visualized with the clarity necessary for unequivocal classification. We obtained good identification of electrophoretic variants of these proteins, but, as a result of the many steps between gene and protein quantity, only a small subset of these proteins were quantitatively so reproducable that there was satisfactory discrimination between those 50% and those 100% in protein quantity—a vital prerequisite to the study of null mutations. However, we were successful in developing an algorithm that, with a minimum of operator intervention, would compare the gels of a father, mother, and child, with the objective of identifying characteristics of the child's gel not present in either parent, and so putative mutations (Skolnick and Neel, 1986; Kuick et al., 1991). This approach to mutation requires that gels be run on the child and both parents.

Beginning in 1979, techniques became available for visualizing the DNA fragments resulting from genomic digests on a two-dimensional gel (Fischer and

FIGURE 10.1 A computer-processed image of a silver-stained two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel of the protein contents of peripheral lymphocytes.

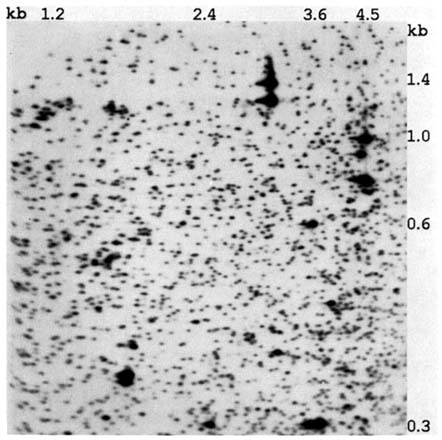

Lerman, 1979; Uitterlinden et al., 1989; Yi et al., 1990; Hatada et al., 1991). We are now exploring the applicability of this approach to studying the genetic effects of the atomic bombs, employing a modified version of the technique described by Hatada et al. (1991) and developed by Asakawa (1995). Hatada et al. (1991) have termed this technique "restriction landmark genomic scanning" (RLGS). A gel based on a lymphocytoid cell line in the RERF collection in shown in Figure 10.2. For a diploid organism such as our species, in the absence of sex-linkage or genetic variation, each spot is the product of two homologous fragments. For these preparations, genomic DNA was digested with NotI and EcoRV restriction enzymes and the NotI-derived 5' protruding ends were ![]() -32P labeled. These fragments were electrophoretically separated in an agarose disc gel, which was subsequently treated with HinfI to further cleave the fragments in situ. The resulting fragments are separated perpendicularly in a 5.25% polyacrylamide gel

-32P labeled. These fragments were electrophoretically separated in an agarose disc gel, which was subsequently treated with HinfI to further cleave the fragments in situ. The resulting fragments are separated perpendicularly in a 5.25% polyacrylamide gel

FIGURE 10.2 A computer-processed image of a two-dimensional gel of enzyme-digested genomic DNA obtained from one of the lymphocytoid cell lines established at RERF.

(33 cm × 46 cm × 0.05 cm). Autoradiograms are then obtained (Asakawa et al., 1994, 1995; Kuick et al., 1995).

The visual comparison of the gel of a child with those of its parents to detect attributes of a child's gel not present in either parent (i.e., a potential mutation) would be extremely demanding, the type of activity guaranteed to lead to a high turnover rate in technicians. Fortunately, the computer algorithm developed for the analysis of protein gels did just as well with these complex DNA images (Asakawa et al., 1994). Among the approximately 2,000 DNA fragments to be visualized on these preparations, we initially identified a subset of approximately 500 for which the coefficient of variation (CV) of spot intensity is ≤0.12; this reproducibility permitted distinguishing between spots of normal intensity and spots with 50% intensity with high accuracy (i.e., two-fragment or one-fragment spots). Already

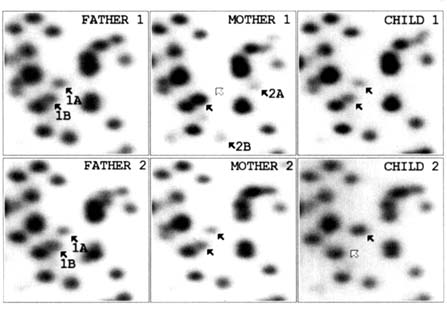

we have identified mendelizing genetic variation involving some 10% of these fragments. Figure 10.3 indicates a comparable area from the gels of two different trios in which segregating variation involving two different polymorphic fragments is present. We believe that with impending technical developments, the battery of fragments suitable for quantitative scoring may increase to 600 or 700. Other enzyme combinations can be used for the genomic digests that precede the gel runs, and, by altering the electrophoretic conditions, larger DNA fragments can be visualized. Currently we are working on three different types of gels for which we believe there is little overlap in the DNA fragments visualized. Furthermore, we have demonstrated the feasibility of recovering (and characterizing the nucleotide sequence of) specific fragments from the gels (Asakawa et al., 1994). Thus, a mutant fragment can be precisely studied. As in the study of proteins, this approach requires running gels on both parents as well as the child.

We would not like to lead you to believe that there is something magic in these new approaches. Their implementation will require a major effort. For each of them, RERF staff and ourselves have attempted to calculate the magnitude of the effort required to reach a significant difference between controls and the children of exposed parents, based on a variety of assumptions considering the doubling dose for the mutational endpoint. There is no time in this presentation to go into the excruciating details of these calculations, but they are available upon request.

Earlier, we made the point that the past genetic studies at RERF examined different aspects of the bomb's potential genetic damage, so that the results of different studies could be combined into a composite picture. These DNA studies will stand alone, since the DNA damage that will be detected could be manifest in a variety of the previous endpoints, varying from impaired survival or a predisposition to cancer to an electrophoretic variant, so that the findings from this study would in principle overlap with the previous findings.

Can A Bridge Be Built Between Somatic Cell Genetic Studies In A-Bomb Survivors and Germ-Line Studies In Their Offspring?

For many years now, the desirability of a somatic cell indicator of genetic damage has been obvious, and several possible systems have been explored at RERF. Four such systems deserve mention: (1) frequency of cytogenetic damage in cultured lymphocytes, (2) frequency of mutations in the glycophorin system, (3) frequency of mutations in the HGPRT system, and (4) frequency of mutant T lymphocytes defective in the expression of the T-cell antigen receptor gene. Time does not permit a discussion of the pros and cons of each of these systems, and in any event, two will be discussed later in this book. Each of these systems has been shown to provide evidence of radiation effects, but each has its limitations as a barometer of germ-line damage. For instance, one of the standbys in cytogenetic studies, the dicentric chromosome, is unstable and either would not be transmitted at gametogenesis or,

FIGURE 10.3 Two examples, in two different trios, of one type of genetic variation encountered in computer images of the two-dimensional DNA gels prepared from the RERF cell lines. In the first example, the father is heterozygous for a segregating variant, the mother is homozygous for the normal fragment, and the child has received a normal fragment from the mother and the variant from the father. In the second example, both parents are heterozygous for a variant but the child has received the normal fragment from both parents.

if transmitted, would probably be incompatible with fetal survival. The nature of the genetic variation revealed by the glycophorin system cannot be studied because the erythrocyte is enucleate, but the phenotypic findings suggest that many of the changes detected are the result of somatic cell crossing over rather than a mutation in the usual sense of the term. For each of these indicators, there is the question of how well it represents the genome as a whole. There is also the question of the nature of the damage decay curve following the initial genetic damage. For these and other reasons, the investigators working with these systems have been

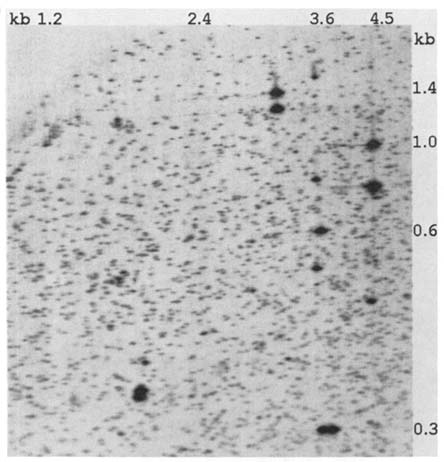

properly cautious in suggesting doubling dose estimates, albeit these are the type of estimates needed for comparison with germinal rates and for guidelines regarding permissible exposures. We would like to suggest a fresh approach to the matter of A-bomb-induced somatic cell damage. Figure 10.4 is a two-dimensional DNA preparation from an individually and directly cloned B lymphocyte transformed by the Epstein-Barr virus, prepared in the Ann Arbor laboratory. The detailed similarity to the preparation based on the Japanese cell lines is striking. Although our studies are still preliminary, we suggest that this technique may represent a new and powerful multi-locus approach to the study of radiation-induced somatic cell damage. This technique has the additional advantage that the results of a study of A-bomb survivors would be directly comparable to the results of a study of their children using the same technique. We remind you that just as is possible for the studies in the F1 cell lines, in principle any apparent somatic mutation that is detected in this system can be precisely characterized.

Cancer Prevalence In Persons Subjected To Increased Radiation Exposures As A Surrogate For Genetic Studies On Their Offspring

There is, in addition to the indicators mentioned in the last section, one final ''somatic cell" indicator of the genetic effects of the atomic bombs: namely, the increase in benign and malignant tumors in the survivors of the atomic bombs. The question is, Can cancer be a "pit canary" for germ-line damage? The best current estimate of the amount of acute ionizing radiation that will double the frequency of solid tissue benign and malignant tumors is 1.66 Sv equivalents (Shigematsu and Mendelsohn, 1995). We regard the similarity of this estimate to the genetic estimate as, at the very least, a useful coincidence. However, Mendelsohn (see Chapter 13) has suggested that the linear relationship between exposure and cancer excess in the survivors is consistent with the radiation having added one additional hit (i.e., mutation) to the complex multi-hit process that characterizes oncogenesis. If this thesis can be sustained, then the cancer doubling dose of 1.66 Sv equivalents is indeed a genetic doubling dose, albeit based on the genes involved in oncogenesis rather than on the genes involved in the indicators we have previously discussed. From the standpoint of risk-setting, there are many important philosophical differences between somatic cell genetic damage and germ-line genetic damage. Most obviously, somatic cell genetic damage runs its course with the death of the affected person, whereas germ-line damage may result in multiple affected persons in multiple generations. Furthermore, the cancers resulting from radiation exposure on average occur some 20–25 years after the exposure; if the exposures are occupational, then the cancers appear in the later years of life. On the other hand, genetic defects resulting from germ-line mutation will generally be apparent at birth and pursue a lifelong course. Nevertheless, an argument can be made to the effect that any public health measures that protect "adequately" against

FIGURE 10.4 A computer-processed image of a two-dimensional DNA gel prepared from an EBV-transformed single-cell lymphocytoid clone derived from an American Caucasian.

an increased incidence of tumors following whole-body radiation exposures will protect adequately against germ-line damage. If accepted, then monitoring for genetic effects becomes somewhat easier, since most populations one might wish to monitor for genetic effects are populations subject to cancer reporting, the populations often supporting cancer registries. Conversely, a population that shows no (or an "acceptable") increase in cancer probably has an "acceptable" level of germ-line genetic damage, which is certainly true of radiation exposures, less certainly true of chemical exposures. This philosophy would have to be applied judiciously: an increase in thyroid malignancy in an area subject to a high fallout of radioactive iodine does not readily translate to genetic damage. The greatest single drawback to adopting this philosophy is the 20–25 year lag between the exposure and

the cancer, so that if in a given situation an increase in cancer were found to be "unacceptable," the germ-line genetic damage has already been done.

"If We Had It To Do Over Again"

Looking back on the long-running complex study of the genetic effects of the atomic bombs, it is important to ask, given all the amazing developments in genetic science these past 50 years, how differently should such a study be designed if it were beginning today? The most obvious change in the research design would be to include studies at the DNA level from the outset. However, it will be some years before it is possible to extrapolate with the desired precision from damage at the DNA level to gross phenotypic effects, and these latter are what the public which ultimately supports such studies really wants to know. Accordingly, we would suggest that any future study should still include most of the components of the study in Japan: frequency of congenital malformations and stillbirths, death rates among liveborn children, growth and development of surviving children, cancer and chromosomal abnormalities in children of exposes. The one study that would probably not be repeated would be a search for electrophoretic and activity variants in proteins. At the time, these studies were the best available approach to detecting nucleotide substitutions and small deletions in DNA, which comprise roughly one-third of the spectrum of radiation-induced damage in DNA. Now the ability to examine DNA directly offers the possibility of much more efficient detection of such lesions. Otherwise, however, looking both backward and forward, we suggest that any future study of the genetic effects of an ionizing or chemical agent ideally should include all but one of the components of the Japanese study plus, now, a DNA component.

There is another aspect to the question of how we would proceed if we had it to do over again based on administrative and psychosocial considerations. With respect to the former, recently an unidentified official at the Department of Energy has said that the early mission of the ABCC had been "absolutely without question" to perform secret research to benefit the weapons program (Macilwain and Swinbanks, 1995). While there was indeed material stamped "secret" in the files of the ABCC in the early days, since any material that touched in any way on the atomic bomb was then classified, there was to my knowledge no research project ever undertaken in secret specifically for the benefit of the military, and I challenge that official to document his statement. Likewise, these are times when the revisionist historians are showing great interest in the atomic bombings and related matters. Thus, I draw your attention to the recent book by Susan Lindee, Suffering Made Real, which depicts the ABCC in its early studies as riding roughshod over Japanese sensibilities in its efforts to collect the data demanded by the Atomic Energy Commission. Lindee has never understood that the ABCC program was set up to be fiercely independent by the Committee on Atomic Casualties of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Research Council. Furthermore,

the recent publications of Schull (1990, 1995), Yamazaki and Fleming (1995), and Neel (1994b) document the very real efforts made to respect Japanese sensibilities and interact with the appropriate local groups.

For appropriate evaluations of these distortions, the reader is referred to the reviews of Putnam (1995) and Finch (1995). Unfortunately, when the uninstructed and naive review Lindee's book, they seem quite willing to accept her distortions. A recent series in the Chugoku Shimbun, Hiroshima's leading newspaper, repeats many of the carping criticisms in Lindee's book, adding some egregious misquotations in the process. It is unfortunate that the authors of these critiques are quite unable or unwilling to grasp and publicize the worldwide significance for humanity—and especially for the Japanese—of these studies.

| This page in the original is blank. |