Effects of Ionizing Radiation: Atomic Bomb Survivors and Their Children (1945-1995) (1998)

Chapter: 13 A Simplified Model of Radiation Carcinogenesis in the Atomic Bomb Survivors

13

A Simplified Model of Radiation Carcinogenesis in the Atomic Bomb Survivors

MORTIMER L. MENDELSOHN

Summary

A simplified model of carcinogenesis combines the linear dose response of solid cancer incidence in the exposed, and the age response of cancer in the controls. Using the Armitage and Doll formulation, the model assumes that cancer in the controls is the result of n time-driven somatic mutations in the evolving stem cell that gives rise to the cancer, where n - 1 is the slope of the logarithm of the cancer rate versus logarithm of age relationship. In radiation-induced cancer, the atomic bomb exposure, in proportion to dose, contributes one and only one of the n mutational events.

The model agrees with actual cancer rates when it uses n taken from the control data, and from reasonable estimates for mutation rate in somatic cells, for numbers of stem cells at risk, and for the number of relevant target oncogenes and cancer-suppressor genes. Also, the model correctly predicts a slope of n - 2 for the log of radiation-induced cancer rate versus log age. The advantages and limitations of the model are discussed.

Introduction

Fifty years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the cancer experience of the survivors provides remarkable detail on human radiation carcinogenicity. The foremost example is the exquisitely linear, nonthresholded,

dose response for the induction of solid cancer (i.e., all cancer except leukemia) as reported by Thompson et al. (1994). Such linearity of response is elegantly simple but is difficult to reconcile mechanistically with two-hit chromosomal induction, a mutation-growth-mutation model, or any other multi-mutational mechanism of cancer induction. It was in thinking about possible explanations for this situation that I happened upon a novel way to frame the carcinogenesis problem (Mendelsohn, 1995, 1996). Donald Pierce and I are currently in the final stages of a formal mathematical description of this evolving formulation, and the present paper will be a qualitative review of the model.

Hypothesis

The simplest mechanism for explaining linear dose responses in radiation biology is by somatic gene mutation. Thus I hypothesize, based on the linear cancer process in the atomic bomb survivors, that the only significant difference between the background and radiation-induced solid cancers is the occurrence of one and only one radiation-induced somatic mutation in the oncogenes and suppressor genes of the evolving stem cell that eventually gives rise to the induced cancer. Based largely on the age distribution of cancer rates and the now-extensive information on multiple genetic defects in human solid cancers, I consider most human solid cancers to arise through a multi-gene mutational mechanism involving a half-a-dozen or so loci. The supporting arguments for these positions follow.

Somatic Mutation In Survivors

The only somatic specific-locus gene-mutation dosimeter that shows a consistent radiation response in the survivors is the flow-cytometric measurement of glycophorin A mutants in erythrocytes (Akiyama et al., 1995). Glycophorin A is a major constituent of the erythrocyte membrane. It has no known function and comes in two equally probable alleles named M and N, following the precedence for the two corresponding and related blood types. In heterozygotes of glycophorin A, every normal erthrocyte simultaneously expresses M and N glycoproteins. Using fluorescent antibodies and flow-cytometric high-speed analysis of erythrocytes, two deviant patterns are detectable. The N0 or M0 outcome in a single erythrocyte is a gene loss (or hemizygosity) of one of the alleles of glycophorin A, with the other allele expressing normally. The NN outcome is a gene duplication (or reduction to homozygosity) in which M glycoprotein is no longer detectable and N is present in double quantity. These outcomes occur about 29 and 20 times, respectively, per million erythrocytes in normal adult subjects. In survivors grouped by dose, the two dose responses are linear and nonthresholded, and differ from each other significantly in slope and y-intercept (Akiyama et al., 1995).

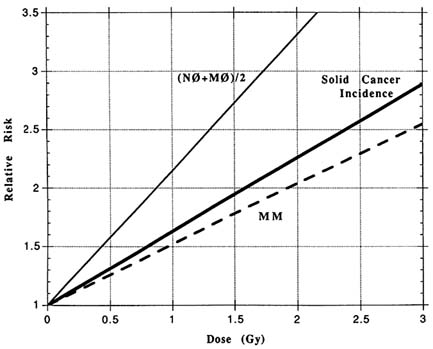

FIGURE 13.1 The dose response for relative risk of three endpoints in the atomic bomb survivors: the incidence of solid cancers, the combined frequencies of the glycophorin A gene loss mutations M0 and N0, and the frequency of the glycophorin A reduction to homozygosity mutation MM. The mutation data are replotted from Akiyama et al. (1995), and the cancer data from Thompson et al. (1994).

The dose responses for cancer and glycophorin A mutation can be compared by expressing them on a common scale of dose and relative risk, as shown in Figure 13.1.

The cancer does response lies midway between the two genetic dose responses, and the three have common shape and roughly common magnitudes of response. Based on this, and in keeping with my hypothesis, one can imagine the cancer induction mechanism to be a combination of gene loss and reduction to homozygosity of a gene with approximately the size and vulnerability of glycophorin A.

Three other somatic genetic dosimeters show inconsistent or absent responses in the survivors (Akiyama et al., 1995). All three are tested in the lymphocyte and are known to respond well to recent radiation exposures both in vitro and in vivo. After radiotherapy, such human lymphocytic mutants have a half-life of a few years

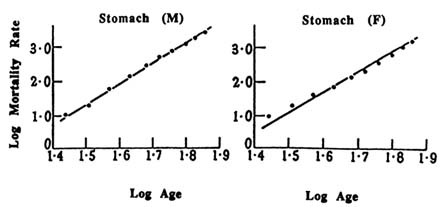

FIGURE 13.2 Log death rate for stomach cancer versus log age, in males (M) and females (F), adapted from Armitage and Doll (1954). In each case, the lines are drawn with a slope of 6, indicating the reasonableness of fit of stomach cancer mortality to age to the 6th power.

in vivo, thus explaining the lack of response in the atomic bomb survivors at four to five decades after exposure.

Cytogenetic analyses of the survivors' lymphocytes show stable increases in balanced chromosomal translocations (Awa, 1991). The dose response is curvilinear upwards and an order of magnitude steeper than the mutation and cancer responses. I will return to this later.

The Role Of Mutation In Carcinogenesis

In 1954, Armitage and Doll published a landmark paper in which they confirmed that the time course of many human cancers is a simple power function of age. It is the property of such functions to be linear in log-log plots of mortality rate versus age. An example, reproduced from their paper, is shown in Figure 13.2. Their accompanying mathematical analysis interprets the power function as a reflection of a cancer process with n successive stages, each independent, irreversible, and roughly similar in likelihood. The biological representation of a stage was unclear to them at the time, but they included the possibility that stages might be due to successive comatic mutation.

Many cancer analysts have dealt with the Armitage and Doll formulation, further confirming the frequent but not universal pattern of the age response and exploring its validity. The prevailing notion has been that somatic mutation is too rare a process to be the sole mechanism for the stages. In recent years, following the lead

of Moolgavkar and Knudson (1981), the trend in cancer modeling has been to focus instead on two mutational stages with an intervening accelerated growth phase that increases the number and sensitivity of target cells and hence the likelihood of the second mutation (see, for example, Little in this volume).

A parallel line of argument in support of multiple mutation stems from the molecular oncologists who, in the past decade, have assembled an impressive body of evidence pointing to oncogene activation and suppressor-gene loss based on gene mutation, chromosome aberration, and gene amplification in human cancer. This wave of discovery culminated in the finding by Fearon and Vogelstein (1990) that in the colon the molecular genetic changes correlate with an evolving succession of precancerous and cancerous lesions, thus emphasizing the link between genomic damage and stages of this disease. While it may not be possible to identify similar staging in other organs, the general pattern has been that each type of adult human cancer has its own constellation of oncogenic change. The patterning, while not exact, fits the notion that each type of solid cancer in adults has ∼6 changes out of a somewhat larger set of candidate genetic sites. I believe that such changes may well represent the stages of Armitage and Doll (1954).

Recently, Vogelstein's group (Papadopoulos et al., 1994) and Kolodner's group (Bronner et al., 1994) simultaneously published the evidence for two mutator genes in human hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Mutations in the two mismatched repair genes occur in approximately 90% of these cancer-prone patients. Since such a mutator mechanism increases the probability of subsequent mutations in the evolving cancer clone, it and other mutator processes make it easier to fit multistage models such as the one proposed here using current somatic mutation and cancer rates.

The Fit Of A Mutational Model In The Survivors

Analysis of the cancer rates in the controls for the atom bomb survivors show linearity of log cancer rate versus log age for solid cancer overall, as well as for the few most common types of cancer which have sufficient data to be analyzed separately. The overall slope is in the range of four to five, suggesting a five- to six-stage mechanism. Breast cancer is a clear exception, showing a two-phased response, with a change of slope around the time of menopause.

With the help of Don Pierce, the feasibility of this modified Armitage and Doll model was tested by using representative values for cancer rate, number of stages, somatic mutation rate, and numbers of stem cells. As an example—assuming six stages, a somatic mutation rate of 5 × 10-5/gene/year, 30 candidate onco- and suppressor genes, and 109 stem cells—the model matches the known cancer rate at age 60. Such a somatic mutation rate is roughly in accord with the mutation rate of human cells in vivo and in vitro, but is likely to be highly dependent on a number of poorly known factors such as the kinetic activity of the stem cells. Similarly, the number of stem cells is an elusive concept, depending heavily on definition and stage of life. This simplified calculation assumed zero mutations at

birth, and a constant-sized stem cell compartment. Embryonic life is very likely a time of high mutation rate, and we know that newborns have significant numbers of several somatic mutations (Manchester et al., 1995, McGinniss et al., 1989). Also, the size of the stem cell compartment probably changes with age, growing in the early years and declining late in life.

Returning to the radiation-induced cancers, a one-mutation dynamic for radiation induction would lead to the magnitude and linearity of dose response shown in Figure 13.1. It would also predict that the radiation-induced cancers by organ would be almost proportional to the control cancers by organ. This result is consistent with organ distributions of control and induced cancers in the atomic bomb survivors (Thompson et al., 1994).

The age pattern of induced cancer should have a close and well-defined relationship to the age pattern of the controls. That is, where n is the number of stages, n - 1 is the slope of the log cancer rate versus log age of the controls, and n - 2 should be the slope of the log cancer rate versus log age of the induced solid cancers. Calculations by Pierce using the atomic bomb data have confirmed this relationship.

In its present state, this model puts no constraint on the ordering of mutations. However, the biology of cancer development may require that certain mutations precede others. Such restrictions would reduce the effective target size for mutation, thereby decreasing the integrated yield of relevant mutations and the corresponding yield of cancers. Severe restrictions could invalidate the model by making background cancer a too-unlikely event.

The model clearly predicts cancer rates that progressively rise with age for most solid cancers, including those that are radiation induced. Biology may again intervene in the form of age-related changes that close off or make less likely a particular channel for cancer development. Two broad examples come to mind. Hormone changes associated with menarche, menopause, or aging could dramatically change the sexually responsive tissues. Diminution of growth in the aged, associated with loss of stem cells, should reduce cancer induction and could be the cause of the frequently seen downward bend in log cancer rate versus log age in the elderly. I predict that the radiation-induced cancers will show parallel changes, regardless of the age at which the subjects are irradiated.

Some Caveats

It is almost certainly a gross oversimplification to reduce the bulk of human carcinogenesis to a sequence of time-driven mutational events. We know that there are profound metabolic and kinetic differences, organ by organ, and that these are confounded by complex secondary factors based on growth, promotion, and environmentally induced mutational injury. One suspects that there are contributions as well from many other aspects of lifestyle and biology. However, regardless of these complexities in background carcinogenesis, the essence of this model is that the added effect of radiation induction may be quite simple.

These results for background and radiation-induced solid cancer are not expected to apply to childhood leukemia. The types of leukemia that arose steeply in the first decade after the bombing and then declined afterward must involve fewer stages and some kind of age-related turn-off of susceptibility. Also, these leukemias have dose responses similar in magnitude and shape to those of chromosomal translocation (Preston et al., 1994).

Similar exceptions may apply to the solid cancers of childhood, genetically based and otherwise. Retinoblastoma needs only one additional mutation in its heritable form, and this occurs so frequently in the involved kindreds that independent bilateral disease is common (Knudson, 1985). The sporadic form of the disease involves two mutations and is unilateral. In both types, the disease is limited to early life and most likely involves a turn-off of susceptibility as the retina matures. Other embryonic tumors share the same kind of early onset and low numbers of required mutation.

A corollary of cancer being caused by time-based mutational processes is that somatic mutation itself should be cumulative with age. While the frequency of glycophorin A mutants in the atomic bomb survivors does increase with age, the response is too flat to fit this model. There are several explanations for why this may be happening. One is that the observed mutations are a composite of (1) long-lived and integrating stem cell mutations, (2) short-lived and non-integrating mutations in the differentiating cells of the committed erythrocyte chain, and (3) false positive, non-integrating technical errors of the method. In overestimating the background, the two non-integrating components of the measurement also lead to underestimation of the relative risk of mutation as given in Figure 13.1.

Yet to be understood with this model is the likely effect of fractionated or low-dose-rate irradiation. At one extreme, the case of a high radiation background, this should appear to the model as an increase in the underlying somatic mutation rate rather than as any effect on the slope of log cancer rate versus log age. At the other extreme, of two acute doses well divided in time, the model predicts essentially no difference from the same total dose delivered in a single fraction. This is largely because of the linearity of the process, or to put it another way, because of the enormous unlikelihood that the same cell lineage would be affected by both fractions.

Finally, I acknowledge that my use of Occam's razor may have carried this model too far on the scale of simplicity. This leaves me in good company, since many others in cancer research have taken the same path in their search for insight into this seemingly impenetrable mystery. I, like they, have embraced simplicity in the hopes that even a brief flash of light may illuminate the truth; the complexity can always be added later. I am grateful to Donald A. Pierce for his contribution to the evolving mathematical formulation and analysis of this material. This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under contract No. W-7405-ENG-48.

| This page in the original is blank. |