Effects of Ionizing Radiation: Atomic Bomb Survivors and Their Children (1945-1995) (1998)

Chapter: 14 Mechanistic Modeling of Radiation-Induced Cancer

14

Mechanistic Modeling of Radiation-Induced Cancer

MARK P. LITTLE

Summary

A variety of models of carcinogenesis are reviewed, and in particular, the multistage model of Armitage and Doll and the two-mutation model of Moolgavkar, Venzon, and Knudson. Both the latter models, and various generalizations of them also, are capable of describing at least qualitatively many of the observed patterns of excess cancer risk following ionizing radiation exposure. However, there are certain inconsistencies with the biological and epidemiological data for both the multistage model and the two-mutation model. In particular, there are indications that the two-mutation model is not totally suitable for describing the pattern of excess risk for solid cancers that is often seen after exposure to radiation, although leukemia may be better fitted by this type of model. Generalizations of the model of Moolgavkar, Venzon, and Knudson that require three or more mutations are easier to reconcile with the epidemiological and biological data relating to solid cancers.

Introduction

One of the principal uncertainties that surround the calculation of population cancer risks from epidemiological data results from the fact that few radiation-exposed cohorts have been followed up to extinction. For example, 40 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, two-thirds of the survivors were still alive (Shimizu et al., 1990). In attempting to calculate lifetime population cancer risks it is therefore important to predict how risks might vary as a function of time after radiation exposure, in particular for that group for whom the uncertainties in

projection of risk to the end of life are most uncertain, namely those who were exposed in childhood.

One way to model the variation in risk is to use empirical models incorporating adjustments for a number of variables (e.g., age at exposure, time since exposure, sex) and indeed this approach has been used in the Fifth Report of the Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiations (BEIR V) Committee (NRC, 1990) in its analyses of data on the Japanese atomic bomb survivors and various other irradiated groups. Recent analyses of solid cancers for these groups have found that the radiation-induced excess risk can be described fairly well by a relative risk model (ICRP, 1991). The time-constant relative risk model assumes that if a dose of radiation is administered to a population, then, after some latent period, there is an increase in the cancer rate, the excess rate being proportional to the underlying cancer rate in an unirradiated population. For leukemia, this model provides an unsatisfactory fit, consequently a number of other models have been used for this group of malignancies, including one in which the excess cancer rate resulting from exposure is assumed to be constant, i.e., the time-constant additive risk model (UNSCEAR, 1988).

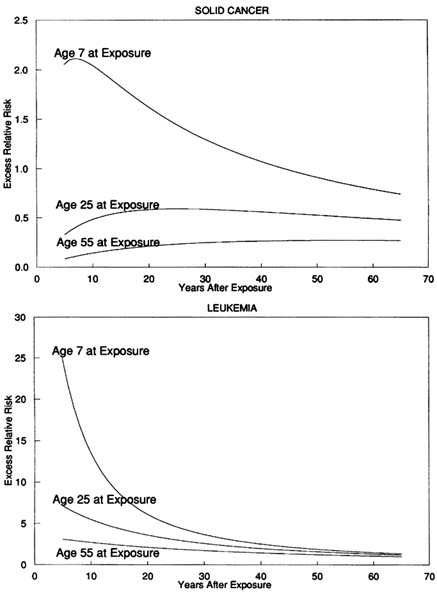

It is well known that for all cancer subtypes (including leukemia) the excess relative risk (ERR) diminishes with increasing age at exposure (UNSCEAR, 1994). For those irradiated in childhood there is evidence of a reduction in the ERR of solid cancer 25 or more years after exposure (Little et al., 1991; Little, 1993; Thompson et al., 1994). For solid cancers in adulthood the ERR is more nearly constant, or perhaps even increasing over time (Little and Charles, 1991; Little, 1993), although there are some indications to the contrary (Weiss et al., 1994). Clearly then, even in the case of solid cancers, various factors have to be employed to modify the ERR.

Associated with the issue of projection of cancer risk over time is that of projection of cancer risk between two populations with differing underlying susceptibilities to cancer. Analogous to the relative risk time projection model one can employ a multiplicative transfer of risks, in which the ratio of the radiation-induced excess cancer rates to the underlying cancer rates in the two populations might be assumed to be identical. Similarly, akin to the additive risk time projection model one can use an additive transfer of risks, in which the radiation-induced excess cancer rates in the two populations might be assumed to be identical. The data that are available suggest that there is no simple solution to the problem (UNSCEAR, 1994). For example, there are weak indications that the relative risks of stomach cancer following radiation exposure may be more comparable than the absolute excess risks in populations with different background stomach cancer rates (UNSCEAR, 1994). The breast cancer relative risks observed in the most recent analysis of the Japanese atomic bomb survivor incidence data (Thompson et al., 1994) are rather higher than those seen in various other datasets, particularly for older ages at exposure (Shore et al., 1986; Miller et al., 1989; Boice et al., 1991).

The observation that sex differences in solid tumor relative excess risk are generally offset by differences in sex-specific background cancer rates (UNSCEAR, 1994) might suggest that absolute excess risks are more alike than relative excess risks. Taken together, these considerations suggest that either a relative or absolute transfer may be warranted; or indeed, the use a hybrid transfer approach, such as that which has been employed by Muirhead and Darby (1987).

Arguably, models that take into account the biological processes leading to the development of cancer can provide insight into these related issues of projection of cancer risk over time and transfer of risk across populations. For example, Little and Charles (1991) have demonstrated that a variety of mechanistic models of carcinogenesis predict an ERR that reduces with increasing time after exposure for those exposed in childhood, while for those exposed in adulthood the ERR might be approximately constant over time. Mechanistic considerations also imply that the interactions between radiation and the various other factors that modulate the process of carcinogenesis may be complex (Leenhouts and Chadwick, 1994), so that in general one would not expect either relative or absolute risks to be invariant across populations.

Armitage-Doll Multistage Model

Mechanistic models of carcinogenesis were originally developed to explain phenomena other than the effects of ionizing radiation. One of the more commonly observed patterns in the age-incidence curves for epithelial cancers is that the cancer incidence rate varies approximately as C · [age] β for some constants C and β. At least for most epithelial cancers in adulthood, the exponent β of age seems to lie between four and six (Doll, 1971). The so-called multistage model of carcinogenesis of Armitage and Doll (1954) was developed in part as a way of accounting for this approximately log-log variation of cancer incidence with age. The model supposes that at age t an individual has a population of X(t) completely normal (stem) cells and that these cells acquire one mutation at a rate M(0)(t). The cells with one mutation acquire a second mutation at a rate M(1)(t), and so on until at the (k 1)th stage the cells with (k - 1) mutations proceed at a rate M(k - 1)(t) to become fully malignant. The model is illustrated schematically in Figure 14.1. It can be shown that when X(t) and the M(i)(t) are constant, a model with k stages predicts a cancer incidence rate which is approximately given by the expression C · [age]k-1 with C = M(0) · M(1) · ‥ · M(k - 1)/(1 · 2 · ‥ · k - 1) (Armitage and Doll, 1954; Moolgavkar, 1978).

In developing their model Armitage and Doll (1954) were driven largely by epidemiological findings, and in particular by the age distribution of epithelial cancers. In the intervening thirty years, there has accumulated substantial biological evidence that cancer is a multistep process involving the accumulation of a number of genetic and epigenetic changes in a clonal population of cells. This evidence is reviewed by the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of

FIGURE 14.1 The Armitage-Doll multistage model.

Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR, 1993). However, there are certain problems with the model proposed by Armitage and Doll (1954) associated with the fact that to account for the observed age incidence curve C · [age]![]() with

with ![]() between four and six, between five and seven stages are needed. For colon cancer there is evidence that six stages might be required (Fearon and Vogelstein, 1990). However, for other cancers there is little evidence that there are as many rate-limiting stages as this. BEIR V (NRC, 1990) surveyed evidence for all cancers and found that two or three stages might be justifiable, but not a much larger number. To this extent the large number of stages predicted by the Armitage-Doll model appears to be verging on the biologically unlikely. Related to the large number of stages required by the Armitage-Doll multistage model are the high mutation rates predicted by the model. Moolgavkar and Luebeck (1992) fitted the Armitage-Doll multistage model to datasets describing the incidence of colon cancer in a general population and in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Moolgavkar and Luebeck (1992) found that Armitage-Doll models with five or six stages gave good fits to these datasets, but that both of these models implied mutation rates that were too high by at least two orders of magnitude. The discrepancy between the predicted and experimentally measured mutation rates might be eliminated, or at least significantly reduced, if account were taken of the fact that the experimental mutation rates are locus-specific. A ''mutation" in the sense in which it is defined in this model might result from the "failure" of any one of a number of independent loci, so that the "mutation" rate would be the sum of the failure rates at each individual locus.

between four and six, between five and seven stages are needed. For colon cancer there is evidence that six stages might be required (Fearon and Vogelstein, 1990). However, for other cancers there is little evidence that there are as many rate-limiting stages as this. BEIR V (NRC, 1990) surveyed evidence for all cancers and found that two or three stages might be justifiable, but not a much larger number. To this extent the large number of stages predicted by the Armitage-Doll model appears to be verging on the biologically unlikely. Related to the large number of stages required by the Armitage-Doll multistage model are the high mutation rates predicted by the model. Moolgavkar and Luebeck (1992) fitted the Armitage-Doll multistage model to datasets describing the incidence of colon cancer in a general population and in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Moolgavkar and Luebeck (1992) found that Armitage-Doll models with five or six stages gave good fits to these datasets, but that both of these models implied mutation rates that were too high by at least two orders of magnitude. The discrepancy between the predicted and experimentally measured mutation rates might be eliminated, or at least significantly reduced, if account were taken of the fact that the experimental mutation rates are locus-specific. A ''mutation" in the sense in which it is defined in this model might result from the "failure" of any one of a number of independent loci, so that the "mutation" rate would be the sum of the failure rates at each individual locus.

Notwithstanding these problems, much use has been made of the Armitage-Doll multistage model as a framework for understanding the time course of carcinogenesis, particularly for the interaction of different carcinogens (Peto, 1977). Thomas (1990) has fitted the Armitage-Doll model with one and two radiation-affected stages to the solid cancer data in the Japanese Life Span Study (LSS) Report 11 cohort of A-bomb survivors. Thomas (1990) found that a model with a total of five

stages, of which either stages one and three or stages two and four were radiation-affected, fitted significantly better than models with a single radiation-affected stage. Little et al. (1992, 1994) also fitted the Armitage-Doll model with up to two radiation-affected stages to the Japanese LSS Report 11 dataset and also to data on various medically exposed groups, using a slightly different technique from that of Thomas (1990). Little et al. (1992, 1994) found that the optimal solid cancer model for the Japanese data had three stages, the first of which was radiation affected, while for the Japanese leukemia data the best fitting model had three stages, the first and second of which were radiation affected.

Both Thomas (1990) and Little et al. (1992, 1994) assumed the ith and the jth stages or mutation rates (M(i - 1), M(j - 1), j > i) in a model with k stages to be (linearly) affected by radiation, and the transfer coefficients [other than M(i - 1) and M(j - 1)] to be constant [as is the stem cell population X(t)]. In these circumstances it can be shown (Little et al., 1992) that if an instantaneously administered dose of radiation d is given at age a, then at age t (> a) the cancer rate is approximately:

for some positive constants μ, α, and β, and where γ is given by:

and γ(·) is the gamma function (Abramowitz and Stegun, 1964).

The first term (μ·tk-1) in expression 14.1 corresponds to the cancer rate that would be observed in the absence of radiation, while the second term (α · d · ai-1 · [t - a]k-i-1) and the third term (β · d · aj-1 · [t - a]k-j-1) represent the separate effects of radiation on the ith and jth stages, respectively. The fourth term (γ · d2 · ai-1 · [t - a]k-j-1), which is quadratic in dose d, represents the consequences of interaction between the effects of radiation on the ith and the jth stages and is only non-zero when the two radiation-affected stages are adjacent (j = i+1). Thus if the two affected stages are adjacent, a quadratic (dose plus dose-squared) relationship will occur, whereas the relationship will be approximately linear if the two affected stages have at least one intervening stage. Another way of considering the joint effects of radiation on two stages is that for a brief exposure, unless the two radiation-affected stages are adjacent, there will be insignificant interaction between the cells affected by radiation in the earlier and later of the two radiation-affected cell compartments. This is simply because very few cells will move between the two compartments in the course of the radiation exposure. If the ith and the jth stages are radiation-affected the result of a brief dose of radiation will be to cause some of the cells which have already accumulated (i - 1) mutations to acquire an extra mutation and move from the (i - 1)th to the ith compartment.

Similarly, it will cause some of the cells which have already acquired (j - 1) mutations to acquire an extra mutation and so move from the (j - 1)th to the jth compartment. It should be noted that the model does not a require that the same cells be hit by the radiation at the ith and jth stages, and in practice for low total doses, or whenever the two radiation-affected stages are separated by an additional unaffected stage or stages, an insignificant proportion of the same cells will be hit (and mutated) by the radiation at both the ith and the jth stages. The result is that, unless the radiation-affected stages are adjacent, for a brief exposure the total effect on cancer rate is approximately the sum of the effects, assuming radiation acts on each of the radiation-affected stages alone. One interesting implication of models with two or more radiation-affected stages is that as a result of interaction between the effects of radiation at the various stages, protraction of dose in general results in an increase in cancer rate, i.e., an inverse dose-rate effect (Little et al., 1992). However, it can be shown that in practice the resulting increase in cancer risk is likely to be small (Little et al., 1992)

The optimal leukemia model found by Little et al. (1992, 1994), having adjacent radiation-affected stages, predicts linear-quadratic dose-response, in accordance with the significant upward curvature which has been observed in the Japanese LSS 11 dataset (Shimizu et al., 1990; Pierce and Vaeth, 1991). This leukemia model, and also that for solid cancer, predicts the pronounced reduction of ERR with increasing age at exposure (see Figure 14.2) which has been seen in the Japanese atomic bomb survivors and other datasets (UNSCEAR, 1994). The optimal Armitage-Doll leukemia model predicts a reduction of ERR with increasing time after exposure for leukemia. At least for those exposed in childhood, the optimal Armitage-Doll solid cancer model also predicts a reduction in ERR with time for solid cancers. These observations are consistent with the observed pattern of risk in the Japanese and other datasets (Little, 1993; UNSCEAR, 1994). Nevertheless, there are indications that the Armitage-Doll model may not provide an adequate fit to the Japanese leukemia data (Little et al., 1995). For this reason, and because of the other problems with the Armitage-Doll model discussed above, one needs to consider a slightly different class of models.

Two-Mutation Model

In order to reduce the biologically implausible number of stages required by their first model, Armitage and Doll (1957) developed a further model of carcinogenesis, which postulated a two-stage probabilistic process whereby a cell following an initial transformation into a pre-neoplastic state (initiation) was subject to a period of accelerated (exponential) growth. At some point in this exponential growth a cell from this expanding population might undergo a second transformation (promotion) leading quickly and directly to the development of a neoplasm. Like their previous model, it satisfactorily explained the incidence of cancer in adults, but was less successful in describing the pattern of certain childhood cancers.

FIGURE 14.2 Predicted excess relative risk at 1 Sv, ERR1Sv, for the optimal Armitage-Doll models fitted to the Japanese A-bomb survivors for cancers other than leukemia (with three stages, the first of which is radiation-affected) and for leukemia (with three stages, the first and second of which are radiation-affected).

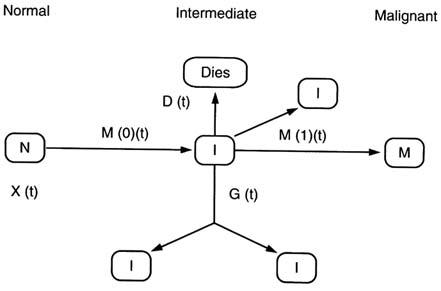

FIGURE 14.3 The two-mutation (MVK) model.

The two-mutation model developed by Knudson (1971) to explain the incidence of retinoblastoma in children took account of the process of growth and differentiation in normal tissues. Subsequently, the stochastic two-mutation model of Moolgavkar and Venzon (1979) generalized Knudson's model by taking account of cell mortality at all stages, as well as allowing for differential growth of intermediate cells. The two-stage model developed by Tucker (1967) is very similar to the model of Moolgavkar and Venzon but does not take account of the differential growth of intermediate cells. The two-mutation model of Moolgavkar, Venzon, and Knudson (MVK) supposes that at age t there are X(t) susceptible stem cells, each subject to mutation to an intermediate type of cell at a rate M(0)(t). The intermediate cells divide at a rate G(1)(t); at a rate D(1)(t) they die or differentiate; at a rate M(1)(t) they are transformed into malignant cells. The model is illustrated schematically in Figure 14.3. In contrast with the case of the (first) Armitage-Doll model, there is a considerable body of experimental biological data supporting this initiation-promotion type of model (see, e.g., Moolgavkar and Knudson, 1981; Tan, 1991). The model has recently been developed to allow for time-varying parameters at the first stage of mutation (Moolgavkar et al., 1988). A further slight generalization of this model to account for time varying parameters at the second stage of mutation was presented by Little and Charles (1991), who also demonstrated that the ERR predicted by the model, when the first mutation rate was subject to instantaneous perturbation, diminished at least exponentially for a sufficiently long time after the perturbation. Moolgavkar et al. (1990) and Luebeck

et al. (1996) have used the two-mutation model to describe the incidence of lung cancer in rats exposed to radon, and in particular to model the inverse dose-rate effect that has been observed in these data. Moolgavkar et al. (1993) have also applied the model to describe the interaction of smoking and radiation as causes of lung cancer in the Colorado Plateau uranium miner cohort.

Recently Moolgavkar and Luebeck (1992) have used models with two or three mutations to describe the incidence of colon cancer in a general population and in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. They found that both models gave good fits to both datasets, but that the model with two mutations implied biologically implausibly low mutation rates. The three-mutation model, which predicted mutation rates more in line with biological data, was therefore somewhat preferable. The problem of implausibly low mutation rates implied by the two-mutation model is not specific to the case of colon cancer, and is discussed at greater length by Den Otter et al. (1990) and Derkinderen et al. (1990), who argue that for most cancer sites a model with more than two stages is required.

Generalized Mvk And Multistage Models

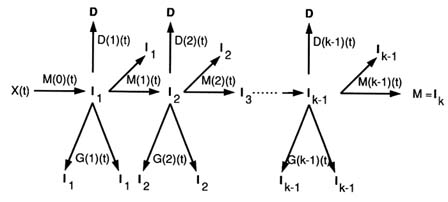

More recently, a number of generalizations of the Armitage-Doll and two- and three-mutation models have been developed (Tan, 1991; Little, 1995). In particular two closely related models have been developed, whose properties have been described in the paper of Little (1995). The first model is a generalization of the two-mutation model of Moolgavkar, Venzon, and Knudson and so will be termed the generalized MVK model. The second model generalizes the multistage model of Armitage and Doll and will be referred to as the generalized multistage model . For the generalized MVK model it may be supposed that at age t there are X(t) susceptible stem cells, each subject to mutation to a type of cell carrying an irreversible mutation at a rate of M(0)( t). The cells with one mutation divide at a rate G(1)(t); at a rate D(1)(t) they die or differentiate. Each cell with one mutation can also divide into an equivalent daughter cell and another cell with a second irreversible mutation at a rate M(1)(t). For the cells with two mutations there are also assumed to be competing processes of cell growth, differentiation, and mutation taking place at rates G(2)(t), D(2)(t), and M(2)(t) respectively, and so on until at the (k - 1)th stage the cells that have accumulated (k - 1) mutations proceed at a rate M(k - 1) (t) to acquire another mutation and become malignant. The model is illustrated schematically in Figure 14.4. The two-mutation model of Moolgavkar, Venzon, and Knudson corresponds to the case k = 2. The generalized multistage model differs from the generalized MVK model only in that the process whereby a cell is assumed to split into an identical daughter cell and a cell carrying an additional mutation is replaced by the process in which only the cell with an additional mutation results, i.e., an identical daughter cell is not produced. The classical Armitage-Doll multistage model corresponds to the case in which the intermediate cell proliferation rates G(i) and the cell differentiation rates D(i) are

FIGURE 14.4 The generalized MVK model.

all zero. It can be shown (Little, 1995) that the ERR for either model following a perturbation of the parameters will tend to zero as the attained age tends to infinity. One can also demonstrate that perturbation of the parameters M(k - 2), M(k - 1), G(k - 1), and D(k - 1) will result in an almost instantaneous change in the cancer rate (Little, 1995).

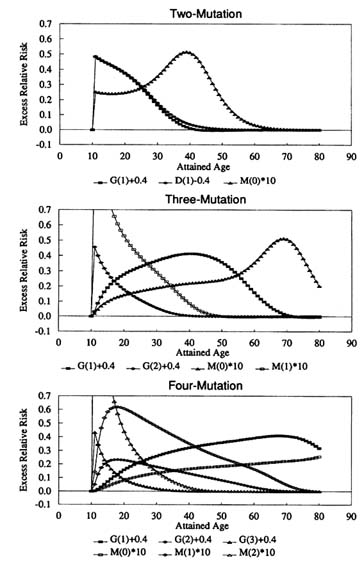

Figure 14.5 shows the calculated ERR for the generalized MVK model in the case where the underlying process has X(t) ≡ 1, G(1) = G(2) = G(3) = 1 y-1, D(1) = D(2) = D(3) = 0.8 y-1, M(0) = M(1) = M(2) = M(3) = 10-4 y-1 and the various parameters are individually altered. In each case the perturbation lasts for a period of a year, after which each parameter returns to its original value.

The first thing to note from Figure 14.5 is that the curves obtained by augmenting the intermediate cell growth rate G(1) for the two-mutation model are almost identical to those obtained by decreasing the intermediate cell death and differentiation rate D(1) by the equivalent amount. Examinations of the perturbed hazard function when G(i) is augmented by 0.4 y-1 and when D(i) is decreased by 0.4 y-1 suggest only very slight differences between these cases for the three-mutation model (or for models with a greater number of mutations). Consequently, only the case in which G(i) is augmented is shown in the lower two panels of Figure 14.5. It can be shown that the hazard function for the generalized multistage model behaves very similarly to that of the corresponding generalized MVK model (Little, 1995). Little (1995) gives additional details of the consequences of perturbation of the model parameters at older ages; the most significant difference is made to the two-mutation model, for which the ERR following perturbation of M(0) is less pronounced shortly after exposure.

Figure 14.5 illustrates the theoretical results of Little (1995) and shows that immediately after perturbing any of the parameters in either of the two-mutation models the ERR quickly increases. Figure 14.5 also shows that perturbing the

FIGURE 14.5 ERR for the generalized MVK model when the number of mutations is between two and four when X ≡ 1, G(1) = ‥ =G(3) = 1 y-1, D(1) = ‥ = D(3) = 0.8 y-1, M(0) = ‥ = M(3) = 10-4 y-1 normally, subject to perturbations at age 10: G(1), ‥, G(3) increased by 0.4 y-1; or D(1) decreased by 0.4 y-1 (two-mutation model only); or M(0), ‥, M(2) multiplied by 10 for 1 year, after which each parameter returns to its original value.

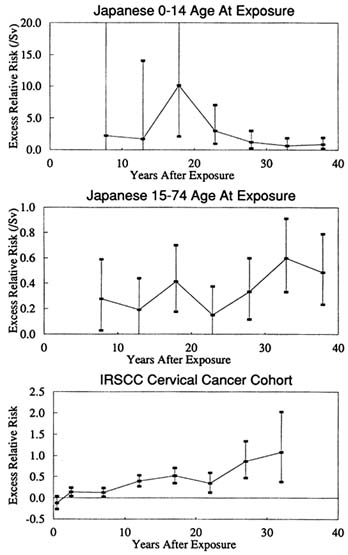

FIGURE 14.6 ERR1Sv and 90% CI for cancers other than leukemia in the Japanese LSS Report 11 data using a neutron relative biological effectiveness of 20, attained age less than 75 years, for ages 0–14 and 15–74 at exposure (using for dose the average dose to breast, large 1intestine, lung, and stomach); ERR and 90% CI for cancers other than leukemia, lung, breast, ovary, and uterus in the IRSCC Cohort Study (Boice et al., 1985).

parameters G(2) or M(1) produces a similar effect in the three-mutation model, and that an analogous change in the hazard function is produced when G(3) or M(2) are perturbed in the four-mutation model. Although they are not shown in Figure 14.5, the results of perturbing the final mutation rate M(k - 1) are even more striking, leading in all cases to an ERR which increases for the duration of the increase of M(k - 1), and which then immediately decreases to near zero; again this result is in accord with the theoretical predictions of Little (1995).

To what extent is the behavior of the excess risk resulting from perturbation of the various parameters in agreement with what has been observed a short time after irradiation in various groups exposed to ionizing radiation? Data on the first five years after exposure are missing for the follow-up of the Japanese A-bomb survivor LSS cohort (Shimizu et al., 1990), but the available data suggest that the ERR for solid cancers increases progressively in the first few years after exposure. As the top two panels of Figure 14.6 indicate, there is only weak evidence for a sudden increase in risk for cancers other than leukemia immediately after the bombings. (The two leftmost datapoints in the top panel correspond to follow-up in the periods approximately 6–10 and 11–15 years after the bombings.) However, apart from the problems of the missing first few years of follow-up, at least in the youngest age-at-exposure group (those under 15 at the time of the bombings) the excess risk is estimated with low precision. For example, the leftmost two ERRs for this age group in the bomb survivors are 2.23 Sv-1 (90% CI <0, 20.48) and 1.73 Sv-1 (90% CI <0, 14.06) (as shown in Figure 14.6) and so are not significantly elevated. There are no strong indications of an elevation in risk in the first five years after radiotherapy for cancers other than leukemia and of the reproductive organs in a study of women followed up for second cancer after radiotherapy for cervical cancer (Boice et al., 1985). This corresponds to the first two datapoints in the bottom panel of Figure 14.6. [Lung cancers are also excluded from the International Radiation Study of Cervical Cancer (IRSCC) data shown in Figure 14.6 because of indications of above-average smoking rates in this cohort (Boice et al., 1985)]. In various other irradiated groups in the first few years after exposure a pattern of risk is observed that is similar to the pattern seen in the atomic bomb survivors and the IRSCC dataset. In particular, for very few of those groups irradiated in childhood are there indications of a sudden increase in risk shortly after irradiation (Little, 1993). To this extent, there are indications of inconsistency between the predictions of the two-mutation model, concerning variation in risks a short time after exposure, and this body of epidemiological evidence relating to solid cancers. When generalized MVK models with two, three, and four mutations are fitted to the Japanese A-bomb survivor solid cancer data, only the two-mutation and three-mutation models provide a satisfactory fit, and in each case only when the first mutation rate M(0) is assumed to be affected by radiation (Little, 1996). Despite the fact that both the two-mutation and three-mutation models give equivalent fits, the predictions of the two models of the pattern of excess risk in the first five years

FIGURE 14.7 A multiple pathway (MVK-type) carcinogenesis model.

after exposure are very different (Little, 1996), as might be expected given the results of Little (1995).

It must be pointed out that Moolgavkar et al. have to some extent circumvented the problem posed by this instantaneous rise in the hazard function after perturbation of the two-mutation model parameters. In their analysis of the Colorado Plateau uranium miners data (1993), Moolgavkar et al. assumed a fixed period of 3.5 years between the appearance of the first malignant cell and the clinical detection of malignancy. However, the use of such a fixed period of latency would only translate a few years into the future the sudden step-change in the hazard function. To achieve the observed gradual increase in excess risk shortly after exposure, a stochastic process must be used to model the transition from the first malignant cell to detectable cancer, such as is provided by the final stage in the three-mutation models described here. In particular, an exponentially growing population of malignant cells could be modeled by a penultimate stage in which G(k - 1) is non-zero and D(k - 1) is zero, the probability of detection of the malignant clone being determined by M(k - 1).

The evidence with respect to the time distribution of excess risk induced by a more or less instantaneously administered dose of radiation for leukemias is rather different. In the IRSCC data (Boice et al., 1985) there is a significant excess risk for acute non-lymphocytic leukemia (ANLL) in the period between one and four years after first treatment. This rapid rise in risk shortly after exposure is paralleled in many other irradiated groups (Little, 1993). Although the data on early years of follow-up are lacking, the indications are that the same is true in the Japanese

A-bomb survivor data (Shimizu et al., 1990; Preston et al., 1994). Comparison of Figure 14.5 with the observed pattern of variation of ERR for leukemia in the Japanese LSS cohort and in other exposed groups indicates that the two-mutation model might well describe the time course of radiation-induced leukemia (Little, 1995). The results of fitting the generalized MVK model, with various numbers of mutations, to the Japanese A-bomb survivor leukemia data indicate that the three-mutation model provides the most satisfactory fit, and then only when the first mutation rate M(0) and the second mutation rate M(1) are assumed to be affected by radiation (Little, 1996).

Multiple Pathway Models

Little et al. (1995) fitted a generalization of the Armitage-Doll model to the Japanese atomic bomb survivor leukemia data which allowed for two cell populations at birth, one consisting of normal stem cells carrying no mutations, the second a population of cells each of which has been subject to a single mutation. The leukemia risk predicted by such a model is equivalent to that resulting from a model with two pathways between the normal stem cell compartment and the final compartment of malignant cells, the second pathway having one fewer stage than the first. This model fitted the Japanese leukemia dataset significantly better, albeit with biologically implausible parameters, than a model that assumed just a single pathway (Little et al., 1995). The findings of Kadhim et al. (1992, 1994), that exposure of mammalian hematopoietic stem cells to alpha particles could result in a general elevation of mutation rates to very much higher than normal levels, implies, if these findings are at all relevant to carcinogenesis, that there might be multiple pathways in the progression from normal stem cells to malignant cells. The mutation rates and indeed the number of rate-limiting stages might be substantially different in these two or more pathways, as Figure 14.7 illustrates. A number of such models are described by Tan (1991), who also discusses at some length the biological and epidemiological evidence for such models of carcinogenesis.

Conclusions

The classical multistage model of Armitage and Doll and the two-mutation model of Moolgavkar, Venzon, and Knudson, and various generalizations of them also, are capable of describing, at least qualitatively, many of the observed patterns of excess cancer risk following ionizing radiation exposure. However, there are certain inconsistencies with the biological and epidemiological data for both the multistage and two-mutation models. In particular, there are indications that the two-mutation model is not totally suitable for describing the pattern of excess risk for solid cancers that is often seen after exposure to ionizing radiation, although leukemia may be better fitted by this type of model. Generalized MVK models

that require three or more mutations are easier to reconcile with biological and epidemiological data relating to solid cancers.

Acknowledgments

This paper makes use of data obtained from the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) in Hiroshima, Japan. RERF is a private foundation funded equally by the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare and the US Department of Energy through the US National Academy of Sciences. The conclusions in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the scientific judgment of RERF or its funding agencies.