LTPP Data Analysis: Improving Use of FWD and Longitudinal Profile Measurements (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Background

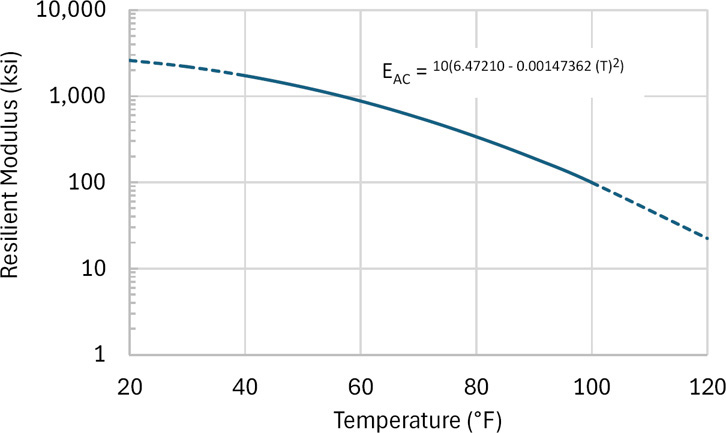

Variation in environmental factors such as surface temperature and moisture content can result in changes in pavement material properties (Zuo 2003). Pavement structures are designed, constructed, and maintained to support traffic loadings and to minimize the impact of climatic factors on pavement performance. For asphalt pavement layers, the most significant environmental factor influencing performance is temperature. The stiffness of the asphalt layer can vary an order of magnitude over the range of typical pavement temperatures. Temperature changes can impact pavement layer stresses and strains, and therefore, fatigue life. When using FWD data to quantify pavement response and backcalculate layer moduli, it is important to quantify the impact of temperatures on the stiffness (or modulus) of the asphalt mixture. This impact, depending on the temperature range, can be significant. For example, an asphalt mix modulus tested in the laboratory at 32°F is approximately 2,000 ksi, while at 70°F, the layer modulus can drop to 500 ksi (Figure 1).

At a minimum, accurate deflection testing of asphalt pavements requires correction from the as-measured temperature to a reference temperature; however, this correction is not always sufficient because asphalt mixtures vary in temperature sensitivity (i.e., not all asphalt mixtures respond the same over a specified temperature range). Therefore, an effective layer moduli-temperature correction factor can be determined by conducting FWD testing (and backcalculation) at multiple temperatures (i.e., over a given day, multiple seasons).

For jointed plain concrete pavements (JPCPs), important environmental factors to consider include the differences in temperature and moisture from the top to the bottom of the slab (i.e., temperature gradient and moisture gradient). Concrete slabs with large temperature or moisture gradients can undergo differential volume changes throughout the depth, causing the slab to curl and warp, and negatively impacting ride quality. Due to truck loading and the self-weight of the slab, curling and warping can also result in increased stress and slab cracking (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Example of distress due to concrete volume change.

Changes in the moisture content of the underlying unbound layer(s) and subgrade soils can result in weakening of these layers, and the presence of water beneath a JPCP slab leads to increased faulting and/or heaving via loss of material due to pumping, expansion of swelling soils, and freeze-thaw damage. Variation in unbound base layers and subgrade soils is also impacted by the presence of moisture (e.g., for fine-grained materials, increased moisture decreases layer stiffness). This is particularly true in areas with frost-susceptible soils and freezing temperatures. (Figure 3). In pavement design, consideration of moduli changes in unbound base and subgrade layers is essential to accurately assess the impact of pavement damage due to the weakening of unbound and subgrade layers.

Figure 3. Example of asphalt pavement damage due to moisture.

To assess the impact of environmental factors on pavement performance it is necessary to quantify material properties and pavement roughness over changes in temperature and moisture. In situ material properties can be quantified by deflection testing at multiple times in each day (monthly or seasonally) over multiple years, calculating changes in deflection, and determining changes in layer moduli through backcalculation procedures. Assessments can be made by measuring longitudinal profile (daily, monthly, seasonally), quantifying and separating the effect of distress progression due to loading and attributing the remaining change in the International Roughness Index (IRI) to environmental factors.

The impact of environmental factors was included as part of the LTPP program, a nationwide research study that was initiated in the late 1980s. In 1992, the LTPP SMP was added to the program to capture the

impacts of environmental factors on pavement performance. The SMP included 85 sections in the United States and Canada representing four climatic zones: wet freeze (WF), wet no freeze (WNF), dry freeze (DF), and dry no freeze (DNF). The SMP sections were located at select General Pavement Studies (GPS) sections and Specific Pavement Studies (SPS) sites. GPS experiments are divided by pavement type (e.g., asphalt and concrete) and SPS experiments include multiple sections per project, each with varying structural factors, including layer thickness, base type, and material properties. SPS-10s only vary the asphalt mix type.

- GPS:

- GPS-1, Asphalt Concrete Pavements on Granular Base

- GPS-2, Asphalt Concrete Pavements on Bound Base

- GPS-3, JPCP

- GPS-4, Jointed Reinforced Concrete Pavements

- GPS-5, Continuously Reinforced Concrete Pavements (CRCP)

- GPS-6, Asphalt Concrete Overlay of Asphalt Concrete Pavements

- GPS-7, Asphalt Concrete Overlay of Portland Cement Concrete Pavements

- GPS-8, Bonded Portland Cement Concrete Overlay (discontinued, replaced by SPS-7)

- GPS-9, Unbonded Portland Cement Concrete Overlay of Portland Cement Concrete Pavements

- SPS:

- SPS-1, Strategic Study of Structural Factors for Flexible Pavements

- SPS-2, Strategic Study of Structural Factors for Rigid Pavements

- SPS-3, Preventive Maintenance Effectiveness of Flexible Pavements

- SPS-4, Preventive Maintenance Effectiveness of Rigid Pavements

- SPS-5, Rehabilitation of Asphalt Concrete Pavements

- SPS-6, Rehabilitation of Jointed Portland Cement Concrete Pavements

- SPS-7, Bonded Portland Cement Concrete Overlay of Portland Cement Concrete Pavements

- SPS-8, Study of Environmental Effects in the Absence of Heavy Loads

- SPS-9, Validation of Asphalt Specification and Mix Design (Superpave®)

- SPS-10, Warm-Mix Asphalt Overlay of Asphalt Pavements

The LTPP SMP sections were evaluated (typically no more than four times per year) for changes in structural properties due to seasonal moisture and temperature variation. During each site visit, FWD data were to be collected a minimum of four times per day on asphalt pavements and three times per day for concrete pavements (Rada et al. 1995). Longitudinal and transverse profile testing and pavement condition surveys were to be conducted concurrently with FWD testing. Seasonal monitoring of temperature and moisture was conducted using (Rada et al. 1995):

- Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) sensors to monitor moisture.

- Resistivity sensors to monitor frost penetration.

- Thermistors to measure the temperature of the subgrade.

- Observation well to monitor the depth of the water table.

- Tipping Bucket Rain Gauge to measure rainfall.

- Ambient temperature probes to monitor air temperature.

Research Objective

The objective of this research is to develop guidelines for improved use of FWD and longitudinal profile measurements data in evaluating pavement condition by considering the effects of temporal and/or diurnal variations. The research shall address both asphalt and concrete pavements and focus on using the data available in LTPP database (including those for SMP test sections).

Report Organization

This report is organized into the following chapters:

Chapter 1—Introduction. This chapter provides background information and project objectives and summarizes the organization of the document.

Chapter 2—Identify the Effects. This chapter summarizes the literature review on the impact of environmental factors on pavement properties and performance, applications of temperature and moisture adjustments to FWD and longitudinal profile measurements, and findings of agency practices in FWD and profile measurements.

Chapter 3—LTPP Seasonal Monitoring Program. This chapter summarizes the instrumentation, and performance, inventory, and materials testing data contained in the SMP database.

Chapter 4—Evaluation of Climatic Conditions. This chapter summarizes and compares the seasonal adjustment factors included in the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) 1993 Guide for the Design of Pavement Structures (1993 AASHTO Guide) and the Enhance Integrated Climatic Model (EICM).

Chapter 5—FWD Deflection Analysis and Climatic Adjustments. This chapter summarizes the deflection basin factors, backcalculated layer moduli, factors influencing FWD measurements, an approach for temperature and moisture adjustments, and a case example illustrating the adjustment approach.

Chapter 6—Longitudinal Profile Analysis and Climatic Adjustments. This chapter summarizes an assessment of the SMP asphalt pavement profile measurement results, an approach for assessing curl and warp in JPCP using the Second-Generation Curvature Index (2GCI), and a case example illustrating the adjustment approach.

Chapter 7—Guidelines for Assessing and Adjusting FWD Measurements. This chapter summarizes an approach for temperature and moisture adjustment for FWD measurements on asphalt pavements.

Chapter 8—Guidelines for Assessing Jointed Plain Concrete Pavement Curl and Warp. This chapter summarizes an approach for temperature and moisture adjustment for profile measurements on JPCP.

Chapter 9—Conclusions and Suggested Research. The report concludes with a summary of key findings and suggested areas for future research.